Difference between revisions of "Gender" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Contracted}}) |

|||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Claimed}}{{Started}} | + | {{Claimed}}{{Started}}{{Contracted}} |

[[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[Category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Sociology]] | [[Category:Sociology]] | ||

Revision as of 21:59, 5 October 2007

Gender, in common usage, refers to the differences between men and women. Gender is an individual's self perception of being male or female. Although "gender" is commonly used interchangeably with "sex," within the academic fields of cultural studies, gender studies and the social sciences in general, the term "gender" often refers to purely social rather than biological differences. Some view gender as a social construction rather than a biological phenomenon. People whose gender identity feels incongruent with their physical bodies may identify themselves as intersex, transgender or genderqueer.

Etymology and usage

The word gender comes from the Middle English gendre, a loanword from Norman-conquest-era Middle French. This, in turn, came from Latin genus. Both words mean 'kind', 'type', or 'sort'. They derive ultimately from a widely attested Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root gen-,[1][2] which is also the source of kin, kind, king and many other English words.[3]

In English, both 'sex' and 'gender' can be used in contexts where they could not be substituted—sexual intercourse, safe sex, sex worker, or on the other hand, grammatical gender. Other languages, like German or Dutch, use the same word, Geschlecht or Geslacht, to refer not only to biological sex, but social differences and grammatical gender as well, making a distinction between 'sex' and 'gender' difficult. In some contexts, German has adopted the English loanword Gender to achieve this distinction. Sometimes Geschlechtsidentität is used for 'gender' (although it literally means 'gender identity') and Geschlecht for 'sex'.

Biological Concept of Gender

Gender can refer to the biological condition of being male or female, or less commonly intersex or "third sex" as applied to humans, or hermaphroditic, as applied to non-human animals and plants.

The biology of gender is scientific analysis of the physical basis for behavioural differences between men and women. It is more specific than sexual dimorphism, which covers physical and behavioural differences between males and females of any sexually reproducing species, or sexual differentiation, where physical and behavioural differences between men and women are described.

Biological research of gender has explored such areas as: intersex physicalities, gender identity, gender roles and sexual preference. Late twentieth century study focussed on hormonal aspects of the biology of gender. With the successful mapping of the human genome, early twenty-first century research started making progress in understanding the effects of gene regulation on the human brain.

History

It has long been known that there are correlations between the biological sex of animals and their behaviour.[4] [5] [6] It has also long been known that human behaviour is influenced by the brain.

The late twentieth century saw an explosion in technology capable of aiding sex research. John Money and Milton Diamond made great progress towards understanding the formation of gender identity in humans. Extensive advances were also made in understanding sexual dimorphism in other animals. For example, there were studies on the effects of sex hormones on rats. The early twenty first century started producing even more amazing results concerning genetically programmed sexual dimorphism in rat brains, prior even to the influence of hormones on development. "Genes on the sex chromosomes can directly influence sexual dimorphism in cognition and behaviour, independent of the action of sex steroids."[7]

Differences between Genders

Brain

The brains of many animals, including humans, are significantly different for males and females of the species.[8] Both genes and hormones affect the formation of many animal brains before "birth" (or hatching), and also behaviour of adult individuals. Hormones significantly affect human brain formation, and also brain development at puberty. Both kinds of brain difference affect male and female behaviour.

In 2006, Alexandra M. Lopes and others published that:

| “ | A sexual dimorphism in levels of expression in brain tissue was observed by quantitative real-time PCR, with females presenting an up to 2-fold excess in the abundance of PCDH11X transcripts. We relate these findings to sexually dimorphic traits in the human brain. Interestingly, PCDH11X/Y gene pair is unique to Homo sapiens, since the X-linked gene was transposed to the Y chromosome after the human–chimpanzee lineages split.[9] | ” |

Although men have a larger brain size, even when adjusted for body mass, there is no definite indication that men are more intelligent than women. In contrast, women have a higher density of neurons in certain parts of the brain. However, difference is seen in the ability to perform certain tasks. On average women are superior on various measures of verbal ability, while men have specific abilities on measures of mathematical and spatial ability.

Richard J. Haier and colleagues at the universities of New Mexico and California (Irvine) found, using brain mapping, that men have more than six times the amount of gray matter related to general intelligence than women, and women have nearly ten times the amount of white matter related to intelligence than men (Haier, Rex E Jung and others, 'Structural Brain Variation and General Intelligence', NeuroImage 23 (2004): 425–433). "These findings suggest that human evolution has created two different types of brains designed for equally intelligent behavior," according to Haier. Gray matter is used for information processing, while white matter consists of the connections between processing centers.

Aptitude

A 2001 report by Richard J. Coley of the ETS found that females often outperformed males on various measures of verbal ability, while males tended to outperform females on measures of mathematical and spatial ability. [1]

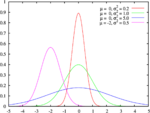

Studies have shown that men show a greater variance in scores than females. The average scores of young men and women in mathematics, for example, will be close, but there will be more men than women in the very low scores and in the very high scores. In this sense, the red bell curve in the diagram represents women, compared to men in green.[10] There is evidence to suggest that forms of autism may be essentially extreme expressions of certain typically male characteristics.[11] [12] This is represented by the blue in the diagram.

Behavior

Hormones have been linked with male aggression.[13]

For an illustrated description of clear differences between male and female brain response to pain see Laura Stanton and Brenna Maloney, 'The Perception of Pain', Washington Post, 19 December 2006.

Nature or nurture

There is a lot of variation in men and women that is not yet understood. It cannot be proven that male-ness or female-ness is 100% biological (in fact virtually all studies show that it is not). However, it is also probably true that male-ness and female-ness are not 100% determined by upbringing and culture (social determinism). These issues remain an area of ongoing research, with profound relevance for people of many different types. One journal (Genes, Brains and Behavior) is devoted specifically to research in this area.

Social Concept of Gender

Since the 1950s, the term gender has been increasingly used to distinguish a social role (gender role) and/or personal identity (gender identity) distinct from biological sex. Sexologist John Money wrote in 1955, "[t]he term gender role is used to signify all those things that a person says or does to disclose himself or herself as having the status of boy or man, girl or woman, respectively. It includes, but is not restricted to, sexuality in the sense of eroticism."[14] Elements of such a role include clothing, speech patterns, movement and other factors not solely limited to biological sex.

Many societies categorize all individuals as either male or female—however, this is not universal. Some societies recognise a third gender[15]—for instance, the Two-Spirit people of some indigenous American peoples, and hijras of India and Pakistan[16]—or even a fourth[17] or fifth.[18] Such categories may be an intermediate state between male and female, a state of sexlessness, or a distinct gender not dependent on male and female gender roles. Joan Roughgarden argues that in some non-human animal species, there can also be said to be more than two genders, in that there might be multiple templates for behavior available to individual organisms with a given biological sex.[19]

There is debate over to what extent gender is a social construct and to what extent it is a biological construct. One point of view in the debate is social constructionism, which suggests that gender is entirely a social construct. Contrary to social constructionism is essentialism which suggests that it is entirely a biological construct. Others' opinions on the subject lie somewhere in between.

Some gender associations are changing as society changes, yet much controversy exists over the extent to which gender roles are simply stereotypes, arbitrary social constructions, or natural innate differences.

Gender in Law

A person's sex as female or male has legal significance—sex is indicated on government documents, and laws provide differently for women and men. Some examples of how sex and gender are legally relevant: many pension systems have different retirement ages for men or women, and usually marriage is only available to opposite-gender couples, whereas a civil partnership is often only available for same-sex couples.

The question then arises as to what legally determines whether someone is male or female. In most cases this can appear obvious, but the matter is complicated for intersexual or transgender people. Different jurisdictions have adopted different answers to this question. Almost all countries permit changes of legal gender status in cases of intersexualism, when the gender assignment made at birth is determined upon further investigation to be biologically inaccurate—technically, however, this is not a change of status per se. Rather, it is recognition of a status which was deemed to exist unknown from birth. Increasingly, jurisdictions also provide a procedure for changes of legal gender for transgender people.

Gender assignment, when there are any indications that genital sex might not be decisive in a particular case, is normally not defined by any single definition, but by a combination of conditions, including chromosomes and gonads. Thus, for example, in many jurisdictions a person with XY chromosomes but female gonads could be recognised as female at birth.

The ability to change legal gender for transgender people in particular has given rise to the phenomena in some jurisdictions of the same person having different genders for the purposes of different areas of the law. For example, in Australia prior to the Re Kevin decisions, a transsexual person could be recognised as the gender they identified with under many areas of the law, e.g., social security law, but not for the law of marriage. Thus, for a period it was possible for the same person to have two different genders under Australian law.

It is also possible in federal systems for the same person to have one gender under state law and a different gender under federal law (e.g., suppose the state recognises gender transitions, but the federal government does not).

Gender in Religion

In Taoism, yin and yang are considered feminine and masculine, respectively.

In Christianity, God is described in masculine terms; however, the Church has historically been described in feminine terms.

Of one of the several forms of the Hindu God, Shiva, is Ardhanarishwar (literally half-female God). Here Shiva manifests himself so that the left half is Female and the right half is Male. The left represents Shakti (energy, power) in the form of Goddess Parvati (otherwise his consort) and the right half Shiva. Whereas Parvati is the cause of arousal of Kama (desires), Shiva is the killer. Shiva is pervaded by the power of Parvati and Parvati is pervaded by the power of Shiva.

While the stone images may seem to represent a half-male and half-female God, the true symbolic representation is of a being the whole of which is Shiva and the whole of which is Shakti at the same time. It is a 3-D representation of only shakti from one angle and only Shiva from the other. Shiva and Shakti are hence the same being representing a collective of Jnana (knowledge) and Kriya (activity).

Adi Shankaracharya, the founder of non-dualistic philosophy (Advaita–"not two") in Hindu thought says in his "Saundaryalahari"—Shivah Shaktayaa yukto yadi bhavati shaktah prabhavitum na che devum devona khalu kushalah spanditam api " i.e., It is only when Shiva is united with Shakti that He acquires the capability of becoming the Lord of the Universe. In the absence of Shakti, He is not even able to stir. In fact, the term "Shiva" originated from "Shva," which implies a dead body. It is only through his inherent shakti that Shiva realizes his true nature.

This mythology projects the inherent view in ancient Hinduism, that each human carries within himself both male and female components, which are forces rather than sexes, and it is the harmony between the creative and the annihilative, the strong and the soft, the proactive and the passive, that makes a true person. Such thought, leave alone entail gender equality, in fact obliterates any material distinction between the male and female altogether. This may explain why in ancient India we find evidence of homosexuality, bisexuality, androgyny, multiple sex partners and open representation of sexual pleasures in artworks like the Khajuraho temples, being accepted within prevalent social frameworks.[20]

Gender in Language

Natural languages often make gender distinctions. These may be of various kinds:

- Grammatical gender, a property of some languages in which every noun is assigned a gender, often with no direct relation to its meaning. For example, Spanish muchacha (grammatically feminine), German Mädchen (grammatically neuter), and Irish cailín (grammatically masculine) all mean "girl." The terms "masculine" and "feminine" are generally preferred to "male" and "female" in reference to grammatical gender.

- The traditional use of different vocabulary by men and women. See, for instance, Gender differences in spoken Japanese.

- The asymmetrical use of terms that refer to males and females. Concern that current language may be biased in favor of males has led some authors in recent times to argue for the use of more Gender-neutral language in English and other languages.

Connectors and fasteners

In electrical and mechanical trades and manufacturing, and in electronics, each of a pair of mating connectors or fasteners (such as nuts and bolts) is conventionally assigned the designation male or female. The assignment is by direct analogy with animal genitalia; the part bearing one or more protrusions, or which fits inside the other, being designated male and the part containing the corresponding indentations or fitting outside the other being female.

Music

In western music theory, keys, chords and scales are often described as having major or minor tonality, sometimes related to masculine and feminine. By analogy, the major scales are masculine (clear, open, extroverted), while the minor scales are given feminine qualities (dark, soft, introverted). German uses the word Tongeschlecht ("Tone gender") for tonality, and the words Dur (from Latin durus, hard) for major and moll (from Latin mollis, soft) for minor.

- See Major and minor.

Notes

- ↑ Julius Pokorny, 'gen', in Indogermanisches etymologisches Wörterbuch, (Bern: Francke, 1959, reprinted in 1989), pp. 373-75. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ↑ 'genə-', in 'Appendix I: Indo-European Roots', to The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 2000). Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ↑ Your Dictionary.com, 'Gen', reformatted from AHD. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- ↑ Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, (London: John Murray, 1859).

- ↑ Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, 2 volumes, (London: John Murray, 1871).

- ↑ Helena Cronin, The Ant and the Peacock: Altruism and Sexual Selection from Darwin to Today, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

- ↑ Skuse, David H (2006). Sexual dimorphism in cognition and behaviour: the role of X-linked genes. European Journal of Endocrinology 155: 99-106.

- ↑ Robert W Goy and Bruce S McEwen. Sexual Differentiation of the Brain: Based on a Work Session of the Neurosciences Research Program. MIT Press Classics. Boston: MIT Press, 1980.

- ↑ Alexandra M. Lopes and others,'Inactivation status of PCDH11X: sexual dimorphisms in gene expression levels in brain', Human Genetics 119 (2006): 1–9.

- ↑ Camilla Persson Benbow and Julian C Stanley, 'Sex Differences in Mathematical Reasoning Ability: More Facts', Science 222 (1983): 1029-1031.

- ↑ Simon Baron-Cohen, 'The Extreme-Male-Brain Theory of Autism', in H Tager-Flusberg (ed.), Neurodevelopmental Disorders, (Boston: The MIT Press, 1999).

- ↑ Simon Baron-Cohen. Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind. (Boston: The MIT Press, 1997).

- ↑ Elizabeth J. Susman, Gale Inoff-Germain, Editha D. Nottelmann, and others, 'Hormones, Emotional Dispositions, and Aggressive Attributes in Young Adolescents', Child Development 58 (1987): 1114-1134.

- ↑ Money, J. (1955). "Hermaphroditism, gender and precocity in hyperadrenocorticism: Psychologic findings." Bulletin of the Johns Hopkins Hospital 96, 253–264.

- ↑ Herdt, Gilbert (ed.) (1996). Third Sex Third Gender: Beyond Sexual Dimorphism in Culture and History. ISBN 0-942299-82-5

- ↑ Nanda, Serena (1998). Neither Man Nor Woman: The Hijras of India. Wadsworth Publishing. ISBN 0-534-50903-7

* Reddy, Gayatri (2005). With Respect to Sex: Negotiating Hijra Identity in South India. (Worlds of Desire: The Chicago Series on Sexuality, Gender, and Culture), University Of Chicago Press (July 1, 2005). ISBN 0-226-70756-3 - ↑ Roscoe, Will (2000). Changing Ones: Third and Fourth Genders in Native North America. Palgrave Macmillan (June 17, 2000) ISBN 0-312-22479-6

- ↑ Graham, Sharyn (2001), Sulawesi's fifth gender, Inside Indonesia, April-June 2001.

- ↑ Roughgarden, Joan. (2004) Evolution's Rainbow: Diversity, Gender, and Sexuality in Nature and People. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24073-1

- ↑ "The Male-Female Hologram," Ashok Vohra, Times of India, March 8, 2005, Page 9

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chafetz, J. S. Masculine/feminine or human? An overview of the sociology of sex roles. 1st ed. 1974, 2nd ed. 178. Itasca, IL: F. E. Peacock. ISBN 0875812317

- Baron-Cohen, Simon. The Essential Difference: The Truth about the Male and Female Brain. New York: Perseus Books Group, 2003. ISBN 046500556X

- Brizendine, Louann. The Female Brain. New York: Morgan Road Books, 2006. ISBN 0767920104

- Brown, Donald E. Human Universals. New York: McGraw Hill, 1991. ISBN 0877228418

- Kimura, Doreen. Sex and Cognition. MIT Press, 1999. ISBN 0262611643

- Moir, Anne and David Jessel. Brain Sex: The Real Difference Between Men and Women. ISBN 0385311834

- Pinker, Steven. The Blank Slate: A Modern Denial of Human Nature. London: Penguin Books, 2002. ISBN 0142003344

External links

- International Behavioural and Neural Genetics Society

- Kritz, Francesca Lunzer. 'Not Feeling Each Other's Pain: Men and Women Hurt Differently – and Some of The Difference May Really Be in Their Heads'. The Washington Post, 19 December 2006. Page HE01.

- Marks, Jonathan. 'Essay 8: Primate Behavior'. In The Un-Textbook of Biological Anthropology. Unpublished, 2007.

- Pinker vs. Spelke. 'The Science of Gender and Science'. Edge (The Third Culture) 16 May, 2005. (multimedia record of public debate)

- Rabinowicz T, and others. 'Gender differences in the human cerebral cortex: more neurons in males; more processes in females'. Journal of Child Neurology 14 (1999): 98-107.

- Runyan, Andrea. 'Sex Is More Than Socialization'. epowiki, August 18, 2005.

- Shaywitz, BA, and others. 'Sex differences in the functional organisation of the brain for language'. Nature 373 (1995): 607-609.

- Genes, Brains and Behavior

- Children's Gender Beliefs

- Gendercide Watch: a project of the Gender Issues Education Foundation (GIEF), a registered charitable foundation based in Edmonton, Alberta

- WikEd—Gender Differences

- WikEd—Gender Inequities in the Classroom

- 'gender' The Maven's Word of the Day June 12, 1998.

- Gender Equality as Smart Economics - A New World Bank Group Action Plan, at the World Bank "Gender and Development" site.

- Gender, Development and the HIV Epidemic, at the UNDP site.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.