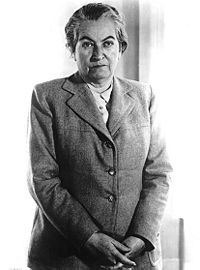

Gabriela Mistral

| |

| Pseudonym(s): | Gabriela Mistral |

|---|---|

| Born: | April 7, 1885 Vicuña, Chile |

| Died: | January 10, 1957 Hempstead, New York |

| Occupation(s): | poet |

| Nationality: | Chilean |

| Writing period: | 1922-1957 |

Gabriela Mistral (April 7, 1885 – January 10, 1957) was the pseudonym of Lucila de María del Perpetuo Socorro Godoy Alcayaga, a Chilean poet, educator, diplomat and feminist who was the first Latin American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, in 1945. Some central themes in her poems are nature, betrayal, love, a mother's love, sorrow and recovery, travel, and Latin American identity as formed from a mixture of Indian and European influences.

Life

Mistral was born in Vicuña, but was raised in the small Andean village of Montegrande, where she attended the primary taught by her older sister, Emelina Molina. She respected her sister greatly. Her father, Juan Gerónimo Godoy Villanueva, was also a schoolteacher. He abandoned the family when she was three years old. At age 14, she began to support herself and her mother by working as a teacher's aide in the seaside town of Compania Baja, near La Serena, Chile. Her mother, Petronila Alcayaga, a seamstress, died in 1929 - Gabriela dedicated the first section of the book Tala (Tree Fall) to her.

In 1904 Mistral published some early poems, such as Ensoñaciones, Carta Íntima ("Intimate Letter") and Junto al Mar, in the local newspaper El Coquimbo: Diario Radical, and La Voz de Elqui using various pseudonyms.

In 1906, while working as a teacher, Mistral met Romeo Ureta, a railway worker, who killed himself in 1909. The profound effects of death were already in the poet's work; writing about his suicide led the poet to consider death and life more broadly than previous generations of Latin American poets. Mistral had passionate friendships with various men and women, and these impacted her writings.

Formal recognition came on December 12, 1914, when Mistral was awarded first prize in a national literary contest Juegos Florales in Santiago, with the work Sonetos de la Muerte (Sonnets of Death). She had been using the pen name Gabriela Mistral since 1909 for many of her writing. After winning the Juegos Florales she rarely used her given name of Lucila Godoy for her publications. She formed her pseudonymn from the two of her favorite poets, Gabriele D'Annunzio and Frédéric Mistral or, as another story has it, from a composite of the Archangel Gabriel and the Mistral wind of Provence.

Mistral's meteoric rise in Chile's national school system continued in 1921, when she defeated another, more politically-connected candidate, to be named director of the newest and most prestigious girls' school in Chile. She left Chile the following year, when she was invited to Mexico by that country's Minister of Education, Jose Vasconcelos. He had her join in the nation's plan to reform libraries and schools, to start a national education system. That year she published Desolación in New York, which won her international acclaim. A year later she published Lecturas para Mujeres (Readings for Women), a text in prose and verse that celebrates motherhood, childhood education, and nationalism. Following almost two years in Mexico she toured Europe and returned to Chile, where she formally retired from the nation's education system. In recognition of her services to education, she eventually received the academic title of Spanish Professor from the University of Chile, although her formal education ended before she was 12 years old.

Mistral's international stature led to lectures first in the United States and then in Europe. In 1924, while traveling to Europe for the first time, she published Ternura (Tenderness) in Madrid, a collection of lullabies and rondas written primarily for children but often focused on the female body.

The following year Mistral returned to Latin America and toured Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina. Back in Chile, she was given a pension and retired from teaching.

Mistral lived primarily in France and Italy between 1925 and 1933. During these years she worked for the League for Intellectual Co-operation of the League of Nations. She also taught at Barnard College of Columbia University, Vassar College and the University of Puerto Rico at Rio Piedras.

Like many Latin American artists and intellectuals, Mistral served as a consul from 1932 until her death, working in Naples, Madrid, Lisbon, Nice, Petrópolis, Los Angeles, Santa Barbara, Veracruz, Mexico, Rapallo and Naples, Italy, and New York. As consul in Madrid, she had occasional professional interactions with another Chilean consul and Nobel Prize winner, Pablo Neruda, and she was among the earlier writers to recognize the importance and originality of his work, which she had known while he was a teenager, and she as school director in his home town of Temuco. As Neruda, Gabriela Mistral became a supporter of the Popular Front which led to the election of the Radical Pedro Aguirre Cerda in 1938. She published hundreds of articles in magazines and newspapers throughout the Spanish-speaking world. Among her confidantes were Eduardo Santos, President of Colombia, all of the elected Presidents of Chile from 1922 to her death in 1957, and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Tala appeared in 1938, published in Buenos Aires with the help of longtime friend and correspondent Victoria Ocampo. The proceeds for the sale were devoted to children orphaned by the Spanish Civil War. This volume includes many poems celebrating the customs and folklore of Latin America as well as Mediterranean Europe. Mistral uniquely fuses these locales and concerns, a reflection of her identification as "una india vasca," her European Basque-Indigenous Amerindian background.

In August 14, 1943 Mistral's 17-year-old nephew Juan Miguel killed himself. The grief of this death, as well as her responses to tensions of the Cold War in Europe and the Americas, are the subject of the last volume of poetry published in her lifetime, Lagar, which appeared in 1954. A final volume of poetry, Poema de Chile, was edited posthumously by her friend Doris Dana, and published in 1967. Poema de Chile describes the poet's return to Chile after death, in the company of an Indian boy from the Atacama desert, and an Andean deer, the huemul.

In November 15, 1945, Mistral became the first Latin American woman to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature. She received the award in person from King Gustav of Sweden on December 10, 1945. In 1947 she received a doctor honoris causa from Mills College, Oakland, California. In 1951 she was awarded the long overdue National Literature Prize in Chile.

Poor health eventually slowed Mistral's traveling. During the last years of her life she made her home in Hempstead, New York, where she died from cancer of the pancreas on January 10, 1957, aged 67. Her remains were returned to Chile nine days later. The Chilean government declared three days of national mourning, and hundreds of thousands of Chileans came to pay her their respects.

Some of Mistral's best known poems include: Piececitos de Niño, Balada, Todas Íbamos a ser Reinas, La Oración de la Maestra, El Ángel Guardián, Decálogo del Artista and La Flor del Aire.

Selected bibliography

- Sonetos de la Muerte (1914)

- Desolación (1922)

- Lecturas para Mujeres (1923)

- Ternura (1924)

- Nubes Blancas y Breve Descripción de Chile (1934)

- Tala (1938)

- Antología (1941)

- Lagar (1954)

- Recados Contando a Chile (1957)

- Poema de Chile (1967, published posthumously)

- Mistral may be most widely quoted in English for Su Nombre es Hoy (His Name is Today):

- “We are guilty of many errors and many faults, but our worst crime is abandoning the children, neglecting the fountain of life. Many of the things we need can wait. The child cannot. Right now is the time his bones are being formed, his blood is being made, and his senses are being developed. To him we cannot answer ‘Tomorrow,’ his name is today.”

See also

- Gerardo Martinez

- Grito de Lares

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

External links

Retrieved November 8, 2007.

- Gabriela Mistral's documents to be sent to Chile as per accord between diplomats from Chile and the United States. www.endi.com.

- Life and Poetry of Gabriela Mistral. www.poetseers.org.

- her lyric poetry which, inspired by powerful emotions, has made her name a symbol of the idealistic aspirations of the entire Latin American world.. www.angelfire.com.

- Nobel biography. nobelprize.org.

|

1926: Grazia Deledda | 1927: Henri Bergson | 1928: Sigrid Undset | 1929: Thomas Mann | 1930: Sinclair Lewis | 1931: Erik Axel Karlfeldt | 1932: John Galsworthy | 1933: Ivan Alekseyevich Bunin | 1934: Luigi Pirandello | 1936: Eugene O'Neill | 1937: Roger Martin du Gard | 1938: Pearl S. Buck | 1939: Frans Eemil Sillanpää | 1944: Johannes Vilhelm Jensen | 1945: Gabriela Mistral | 1946: Hermann Hesse | 1947: André Gide | 1948: T. S. Eliot | 1949: William Faulkner | 1950: Bertrand Russell |