Difference between revisions of "Filioque clause" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→External links) |

|||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

[[Image:EcumenicalPatriarchBartholomewI.jpg|thumb|left|Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I]] | [[Image:EcumenicalPatriarchBartholomewI.jpg|thumb|left|Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew I]] | ||

| − | In liturgies, when celebrating with bishops from the East, the pope has recited the [[Nicene Creed]] without the ''filioque''. Of special importance is a recent clarification of the ''filioque'' by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, entitled ''The Greek and Latin Traditions Regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit''<ref>[http://www.ewtn.com/library/CURIA/PCCUFILQ.HTM]</ref>. | + | In liturgies, when celebrating with bishops from the East, the pope has recited the [[Nicene Creed]] without the ''filioque''. Of special importance is a recent clarification of the ''filioque'' by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, entitled ''The Greek and Latin Traditions Regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit''<ref>[http://www.ewtn.com/library/CURIA/PCCUFILQ.HTM "The Greek and Latin Traditions Regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit"] www.ewtn.com. Retrieved July 29, 2008.</ref>. |

An official [[Roman Catholic]] document published on August 6, 2000 and written by the future [[Pope Benedict XVI]] when he was [[Cardinal (Catholicism) |Cardinal]] Joseph Ratzinger, [[prefect]] of the [[Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith]]—titled ''[[Dominus Iesus]]'', and subtitled ''On the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church'' quietly leaves out ''filioque'' clause from the Creed without notice or comment. | An official [[Roman Catholic]] document published on August 6, 2000 and written by the future [[Pope Benedict XVI]] when he was [[Cardinal (Catholicism) |Cardinal]] Joseph Ratzinger, [[prefect]] of the [[Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith]]—titled ''[[Dominus Iesus]]'', and subtitled ''On the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church'' quietly leaves out ''filioque'' clause from the Creed without notice or comment. | ||

Revision as of 13:12, 29 July 2008

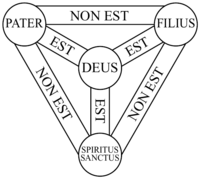

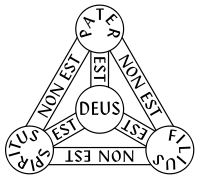

In Christian theology the filioque clause or filioque controversy is a heavily disputed part trinitarian theology that is one of the core differences between Catholic and Orthodox tradition.

The Latin term filioque means "and [from] the son," referring to whether the Holy Spirit "proceeds" from the Father alone or both from the Father and the Son. In the Orthodox tradition, the Nicene Creed reads "We believe in the Holy Spirit ... who proceeds from the Father," while in the Catholic tradition it reads "We believe in the Holy Spirit... who proceeds from the Father and the Son."

The Orthodox position is based on the tradition of the ecumenical councils, which specify "from the Father" only. The Catholic position is based on longstanding traditions of the western Church Fathers, local councils, and several popes. The filioque controversy became a major issue during the so-called Photian schism of the seventh century and later became one of the causes of the Great Schism of 1054, which created a lasting break between the Catholic and Orthodox faiths.

As with many such conflicts, most Christians no longer see the issue as something which should divide them, and in recent decades Catholic and Orthodox leaders have made important steps toward reconciling on this and other matters that divide them.

Background

First Council of Nicea in 325 was concerned primarily with the relationship between God the Father and God the Son, and did not deal with the question of the Holy Spirit's relationship to the Father and the Son. It creed simply stated, "We believe in the Holy Spirit."

In 381, on the basis of John 15:26b—"I will send to you from the Father, the Spirit of truth who goes out from the Father, he will testify about me"—the First Council of Constantinople modified this statement by stating that the Holy Spirit "proceeds from the Father." This creed was confirmed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451.

Origins of the filioque

The aforementioned councils are all considered "ecumenical" and therefore binding on all orthodox Christians. In the West, however, Saint Augustine of Hippo followed Tertullian and Ambrose in teaching that the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father and the Son, though subordinate to neither. Other Latin Church Fathers also spoke of the Spirit proceeding from both the Father and the Son. While familiar in the West, however, this way of speaking was virtually unknown among the ancient churches of the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman Empire.[1]

The first Latin council to add the phrase and the Son (filioque) to its creed was the Synod of Toledo in Spain in 447. The formula was also used in a letter from Pope Leo I to the members of that synod. The addition came about in opposition to fifth century manifestations of a form the Arian "heresy" which was prevalent among the Germanic tribes of Europe. By affirming the Holy Spirit's procession from both the Father and the Son, the bishops at Toledo intended to exclude Arian notions that the Son was something less than a co-eternal and equal partner with the Father from the very beginning of existence.

At a the third synod of Toledo in 589, the ruling Visigoths, who had been Arian Christians, submitted to the Catholic Church and were thus obliged to accept the Nicene Creed with the addition of the filioque. The filoque was later accepted by the Franks, who, under the leadership of Pippin the Younger and his son Charlemagne, rose to dominance in the West, with Charlemagne being crowned Emperor in 800. In the West, the filioque was thus widely accepted as an integral part of the Nicene Creed and an integral part of the battle against the Arian heresy.

Some in the west, however, demonstrated a sensitivity to eastern concerns that the filioque represented an innovation that was clearly not part of the received tradition of the ecumenical councils. In the early ninth century, Pope Leo III stated that although he personally agreed with the filioque, he opposed adopting formally in Rome. As a gesture of unity with the East, he caused the traditional text of the Nicene Creed—without the filioque—to be displayed publicly. This text was engraved on two silver tablets at the tomb of Saint Peter.

However, the practice of adding the filioque was retained in many parts in the West in spite of this papal advice, and by the middle of the eleventh century it had gained a firm foothold in Rome itself. Scholars do not agree as to the exact time of its introduction at Rome, but most assign it to the reign of Benedict VIII.

The Photian schism

In the East, however, no such developments had occurred, and the inclusion of the filoque clause in western versions of the creed was looked upon with suspicion, especially in view of the fact that the canons of the Third Ecumenical Council (in Ephesus in 431) specifically forbade and anathematized any additions to the Nicene Creed.

Meanwhile, in 858, the Byzantine Emperor Michael III removed Patriarch Ignatius I as patriarch of Constantinople for political reasons and replaced him with the future Saint Photios, a layman and scholar who had previously been imperial secretary and ambassador to Muslims at Baghdad. A controversy ensued, and the emperor called a synod to which Pope Nicholas I was invited. The pope sent legates to participate in the meeting in 861, which formally confirmed Photios as patriarch. On learning of the council's decision the next year, the pope was outraged that the synod had not considered Rome's claims to jurisdiction over the newly converted Christians of Bulgaria and consequently excommunicated his own delegates. He then convened a council in Rome in 863, in which he excommunicated Photios and deposed him on the basis that his appointment as patriarch of Constantinople was not canonical. He recognized Ignatius as the legitimate patriarch instead. Thus Rome and Constantinople found themselves, not for the first time in their history, in schism.

The filioque entered the controversy in 867, when Photius formally rejected the pope's claims and cited the filioque as proof that Rome had a habit of overstepping its proper limits not only in matters of church discipline but also in theology. A council was convened with over a thousand clergymen attending. This synod excommunicated Pope Nicholas and condemned his claims of papal primacy, his interference in the newly converted Bulgaria, and the innovative addition of the filioque clause to the western version of the Nicene Creed. The filioque was now formally considered by the Orthodox Church to be a heresy.

The murder of Emperor Michael by the usurper Basil the Macedonian in 867 resulted in the actual deposition of Photios and the re-installation of Ignatius. On the death of Ignatius in October 877, Photius again resumed office, having been recommended by Ignatius prior to his death. He was forced to resign in 886 when Leo VI took over as emperor and spent the rest of his life as a monk in exile in Armenia. He is revered by the Orthodox today as a saint.

Further East-West controversy

In 1014, the German Emperor Henry II visited Rome for his coronation and found to his surprise that the Nicene Creed was not used during the Mass. At his request, the Pope Benedict VIII included the Creed with the filioque, after the reading of the Gospel. This was the first time the phrase was known to be used in the Mass at Rome.

In 1054 the issue contributed significantly to the Great Schism of the East and West, when Pope Leo IX formally included the term in his official expression of faith and the Catholic and Orthodox churches each declared the other guilty of heresy for including or not including the filioque in their respective creeds.

In 1274, at the Second Council of Lyons, the Catholic Church officially condemned those who "presume to deny" that the holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son.

Council of Florence

At the Council of Florence in the fifteenth century, Byzantine Emperor John VIII Palaeologus, Patriarch Joseph of Constantinople, and other bishops from the East traveled to northern Italy, in hope to gain reconciliation with the West and the aid of Roman armies in their conflict with the Ottoman Empire.

After extensive discussion, they acknowledged that some early Latin Church Fathers spoke of the procession of the Spirit differently from the Greek Fathers. The Western usage was held not to be a heresy and no longer a barrier to restoration of full communion. All but one of the Orthodox bishops present, Mark of Ephesus, agreed and signed a decree of union between East and West in 1439.

For a brief period, the Catholic and Orthodox Churches were once again in communion. However, the reconciliation achieved at Florence was soon destroyed. Many Orthodox faithful and bishops rejected the union and would not ratify it, seeing it as a compromise of theological principle in the interest of political expediency. Moreover, the promised Western armies were too late to prevent the Fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453. From that time onward, the Turks encouraged separation from the West, which remained an adversary to Islamic political and military dominance.

For his stand against the filioque and compromise with papal supremacy, Mark of Ephesus came to be venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and is often honored as a pillar of Orthodoxy.

Recent discussions and statements

In the recent past, many Catholic theologians have written on the filioque with an ecumenical intention. Yves Congar, O.P., argues that varying formulations may be seen not as contradictory but as complementary. Irenee Dalmais, O.P. points out that East and West have different, yet complementary, pneumatologies, theologies of the Holy Spirit. Avery Dulles, S.J., traces the history of the filioque controversy and weighs pros and cons of several possibilities for reconciliation. Eugene Webb makes use of the pneumatology of Bernard Lonergan, S.J.

Several Orthodox theologians have also considered the filioque anew, with a view to reconciliation of East and West. Theodore Stylianopoulos, for one, provides an extensive, scholarly overview of the contemporary discussion. Bishop Kallistos of Diokleia says that he now considers the filioque dispute to be primarily semantic rather than substantive. Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople has said that all that is necessary for complete reconciliation is resolution of what he calls the "Uniate" problem, the issue Eastern Rite Catholic Churches in Russia. For many Orthodox, the filioque, while still a matter of needing discussion, thus no longer impedes full communion between the Catholic and Orthodox Churches.

In liturgies, when celebrating with bishops from the East, the pope has recited the Nicene Creed without the filioque. Of special importance is a recent clarification of the filioque by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity, entitled The Greek and Latin Traditions Regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit[2].

An official Roman Catholic document published on August 6, 2000 and written by the future Pope Benedict XVI when he was Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith—titled Dominus Iesus, and subtitled On the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church quietly leaves out filioque clause from the Creed without notice or comment.

The filioque clause was the main subject discussed at the meeting of the North American Orthodox-Catholic Theological Consultation, which met at the Hellenic College/Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology in Brookline from June 3 through June 5 2002. These discussions characterized the filioqueissue as what the Greeks call a theologumenon, a theological idea which is open to discussion and is not deemed heretical. Further progress along these lines was made by the North American Orthodox-Catholic Theological Consultation, on October 25, 2003. This document The Filioque: A Church-Dividing Issue?, provides an extensive review of Scripture, history, and theology of the filioque question. Among its conclusion were:

- That, in the future, Orthodox and Catholics should refrain from labeling as heretical each other's traditions on the subject of the procession of the Holy Spirit.

- That the Catholic Church should declare that the condemnation made at the Second Council of Lyons (1274) of those "who presume to deny that the Holy Spirit proceeds eternally from the Father and the Son" is no longer applicable.

In the judgment of the consultation, the question of the filioque is no longer a "Church-dividing" issue.

Notes

- ↑ However, a regional council in Persia in 410 introduced one of the earliest forms of the filioque in its version the creed, specifying that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father "and from the Son."

- ↑ "The Greek and Latin Traditions Regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit" www.ewtn.com. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Kolbaba, Tia M. Inventing Latin Heretics: Byzantines and the Filioque in the Ninth Century. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, 2008. ISBN 9781580441339

- Küng, Hans, and Jürgen Moltmann. Conflicts About the Holy Spirit. New York: Seabury Press, 1979. ISBN 9780816420353

- Haugh, Richard S. Photius and the Carolingians: The Trinitarian Controversy. Belmont, Mass: Nordland Pub. Co, 1975. ISBN 9780913124055

- Ngien, Dennis. Apologetic for Filioque in Medieval Theology. Bletchley, Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2005. ISBN 9781842272763

- Vischer, Lukas. Spirit of God, Spirit of Christ: Ecumenical Reflections on the Filioque Controversy. Faith and order paper, no. 103. London: SPCK, 1981. ISBN 9780281038206

External links

This article incorporates text from the public domain 1907 edition of The Nuttall Encyclopædia.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.