|

|

| (83 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | In [[Christianity|Christian]] [[theology]] the '''filioque clause''' or '''filioque controversy''' is a heavily disputed part trinitarian theology regarding the relationship between God the Son and God the Holy Spirit, that forms a divisive difference between the [[Roman Catholic Church|Roman Catholic]] and [[Eastern Orthodox Church|Eastern Orthodox]] traditions.

| + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

| | | | |

| − | The Latin term ''filioque'' means "and [from] the son." In the Orthodox tradition, the [[Nicene Creed]] reads "We believe in the Holy Spirit ... who proceeds from the Father", while in the Catholic tradition it reads "We believe in the Holy Spirit ... who proceeds from the Father ''and the Son''".

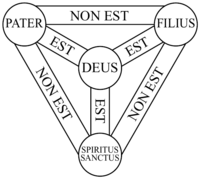

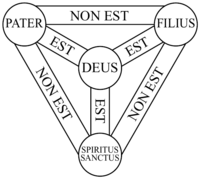

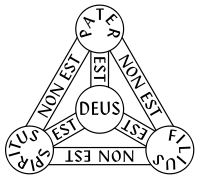

| + | [[Image:Shield-Trinity-Scutum-Fidei-basic.png|thumb|200px|A diagram of the so-called "Shield Trinity" in which the [[Holy Spirit]] seems to "proceed" from both the Father and the Son, in conformity with the notion of the ''filioque'' clause.]] |

| | | | |

| − | ==Development of the creed==

| + | The '''filioque clause''' is a heavily disputed part of Christian trinitarian [[theology]] and one of the core differences between [[Catholic Church|Catholic]] and [[Eastern Orthodox Church|Orthodox]] traditions. The [[Latin]] term ''filioque'' means "and [from] the son," referring to whether the [[Holy Spirit]] "proceeds" from the Father alone or both from the Father ''and'' the Son. In the Orthodox tradition, the [[Nicene Creed]] reads, "We believe in the Holy Spirit … who proceeds from the Father," while in the Catholic tradition it reads "We believe in the Holy Spirit… who proceeds from the Father ''and the Son''." The Orthodox position is based on the tradition of the [[ecumenical councils]], which specify "from the Father" only. The Catholic position is based on longstanding traditions of the western [[Church Fathers]], local councils, and several [[pope]]s. |

| − | First [[Council of Nicea]] in 325 did not deal with the question of the Holy Spirit's relationship to the Father and the Son, stated simply, "We believe in the Holy Spirit." In 381, following John 15:26b, the [[First Council of Constantinople]] modified this statement by stating that the [[Holy Spirit]] "proceeds from the Father." This creed was confirmed at the [[Council of Chalcedon]] in 451.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Historical origins==

| + | Underlying the theological question were issues such as the struggle for supremacy between [[Rome]] and [[Constantinople]] and the right of the [[pope]] to determine the expression of the Creed. The western churches, meanwhile, had used the filioque clause in part to exclude Christians in western Europe who were suspected of sympathizing with [[Arianism]] (a view that introduced sequence into Christian trinitarianism). The ''filioque'' controversy emerged as a major issue during the so-called [[Saint Photios|Photian schism]] of the seventh century and later became one of the causes of the [[Great Schism]] of 1054, which created a lasting break between the Catholic and Orthodox faiths. |

| − | The aforementioned councils are all considered "ecumenical" and therefore binding on all orthodox Christians. In the West, Saint [[Augustine of Hippo]] followed [[Tertullian]] and [[Ambrose]] in teaching likewise that the Spirit proceeded from the Father ''and'' the Son, though subordinate to neither. Other Latin [[Church fathers]] also spoke of the Spirit proceeding from both the Father and the Son. While familiar in the West, however, this way of speaking was virtually unknown in the Greek-speaking, Eastern Roman Empire. However, a regional council in [[Persia]] in 410 introduced one of the earliest forms of the ''filioque'' in its version the creed, specifying that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father "and from the Son."

| + | {{toc}} |

| | + | As with many such theological conflicts, many Christians today no longer see the issue as something which should keep them apart, and in recent decades Catholic and Orthodox leaders have made important steps toward reconciling on this and other matters that divide them. |

| | | | |

| − | The first Latin council to add the phrase ''and the Son'' (''filioque'') to its creed was the [[Synod of Toledo]] in [[Spain]] in 447. The formula was also used in a letter from [[Pope Leo I]] to the members of that synod. The addition came about in opposition to fifth century manifestations the [[Arianism|Arian]] "[[heresy]]," which taught that the Son of "like" rather than "same" substance with the Father and which was prevalent among the Germanic tribes of Europe. By affirming the Holy Spirit's procession from both the Father and the Son, the bishops at Toledo intended to exclude Arian notions that the Son was not actively involved with the Father from the very beginning of existence. At a the third synod of Toledo in 589, the ruling [[Visigoths]], who had been [[Arianism|Arian]] [[Christianity|Christians]], submitted to the Catholic Church and were thus obliged to accept the Nicene Creed with the addition of the ''filioque''.

| + | ==Background== |

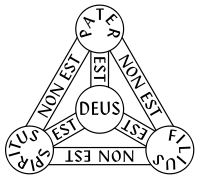

| | + | [[Image:3enighed.svg|thumb|200px|Shield Trinity diagram in which the [[Holy Spirit]] seems to proceed directly from the Father.]] The roots of the ''filioque'' controversy may be found in the differing traditions between eastern and western Christian approaches to the expression of trinitarian theology. The [[Council of Nicea]], in 325 C.E., also known as the [[First Ecumenical Council]], affirmed a belief in the [[Trinity]], but was concerned primarily with the relationship between [[God the Father]] and [[God the Son]]. It did not deal directly with the question of the Holy Spirit's relationship to the Father and the Son. Its creed simply stated, "We believe in the Holy Spirit." |

| | | | |

| − | The ''filoque'' was later accepted by the [[Franks]], who, under the leadership of [[Pippin the Younger]] and his son [[Charlemagne]], rose to dominance in the West, with Charlemagne being crowned Emperor in 800. In the West, the ''filioque'' was thus widely accepted as an integral part of the Nicen Creed.

| + | In 381, the [[First Council of Constantinople]], also known as the Second Ecumenical Council, addressed the issue of the Holy Spirit more directly. On the basis of John 15:26b—"I will send to you from the Father, the Spirit of truth who goes out from the Father, he will testify about me"—it modified Nicea's creed by stating that the [[Holy Spirit]] "proceeds from the Father." This creed was confirmed at the [[Council of Chalcedon]] in 451 C.E. |

| | | | |

| − | ==The Photian schism==

| + | The ''filioque'' controversy was exacerbated by the long-standing struggle between [[Rome]] and [[Constantinople]] for supremacy over the Christian churches in the later [[Roman Empire]]. This contest also played a role in several other theological battles, from the [[Arianism|Arian]] controversy to the struggles over [[Nestorianism]] (a view that Christ consisted of two distinct natures) and [[Monophysitism]] (a view that Christ has only one nature), the so-called [[Meletian schism]], the [[Three Chapters]] controversy, and the battles over [[Iconoclasm]]. Even the elections of several popes became hotly contested, sometimes violent struggles between one party which leaned more toward the Roman emperors in Constantinople and an opposing faction which supported the "barbarian" kings who often controlled Italy and the West. |

| − | [[Image:StPhotios.jpg|thumb|Saint Photios]] | |

| − | In the East, however, no such developments had occurred. In 858, the Byzantine Emperor [[Michael III]] removed [[Patriarch Ignatius I]] as patriarch of Constantinople. with the future Saint [[Photius]], who had previously been imperial secretary and ambassador to [[Muslims]] at Baghdad. However, Ignatius refused to abdicate, and the emperor appealed to [[Pope Nicholas I]] of Rome to settle the matter. The pope then sent legates to participate in a synod at Constantinople in 861 which deposed Ignatius, but apparently under considerable imperial pressure.

| |

| | | | |

| − | The pope thus refused to support the removal of Ignatius and refused to recognize Photius. After the arrival of an embassy from Ignatius in Roma in 862, Pope Nicholas declared Photius to deposed, as well as any bishops who had ordained him and all the clergy he had appointed. In 867, Photius' ''Encyclical to the Eastern Patriarchs'' formally rejected the pope's assertion and cited the ''filioque'' as proof that Rome had a habit of overstepping its proper limits. | + | ==Origins of the ''filioque''== |

| | + | The aforementioned councils were all considered "ecumenical" and, therefore, binding on all orthodox Christians. In the West, however, Saint [[Augustine of Hippo]] followed [[Tertullian]] and [[Ambrose]] in teaching that the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father ''and'' the Son, though subordinate to neither. Other Latin [[Church Fathers]] also spoke of the Spirit proceeding from both the Father and the Son. While familiar in the West, however, this way of speaking was virtually unknown among the ancient churches of the Greek-speaking Eastern [[Roman Empire]]. (However, a regional council in [[Persia]], in 410, introduced one of the earliest forms of the ''filioque'' in its version the creed, specifying that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father "and from the Son.") |

| | | | |

| − | However, the patriarchs of Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem concurred with Rome—at least on the issue of Photius ordination if not on the ''filoque''. In 867 and 869–870, synods in Rome and Constantinople restored Ignatius to his position as patriarch. However, in 877, after the death of Ignatius, Photius again resumed office, but was forced to resign in 886 when [[Leo VI]] took over as emperor. Photius spent the rest of his life as a monk in exile in Armenia. He is revered by the Orthodox today as a saint. He was the first important theologian to accuse Rome of heretical innovation in the matter of the ''filioque''.

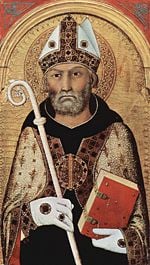

| + | [[Image:Simone Martini 003.jpg|thumb|left|150px|Western [[Church Fathers]] such as [[Augustine of Hippo]] used the ''filioque'' clause, while the phrase was basically unknown to the Greek-speaking churches.]] |

| | | | |

| − | ==Further East-West controversy==

| + | The first Latin council to add the phrase ''and the Son'' ''(filioque)'' to its creed was the [[Synod of Toledo]] in [[Spain]] in 447. The formula was also used in a letter from [[Pope Leo I]] to the members of that synod. The addition came about in opposition to fifth century manifestations of a form the [[Arianism|Arian]] "[[heresy]]" which was prevalent among the Germanic tribes of Europe. By affirming the Holy Spirit's procession from both the Father ''and'' the Son, the bishops at Toledo intended to exclude Arian notions that the Son was something less than a co-eternal and equal partner with the Father from the very beginning of existence. |

| | | | |

| − | In the ninth century, [[Pope Leo III]] stated that although he personally agreed with the ''filioque'', he opposed adopting formally as pope in Rome since it was clearly not part of received tradition of the [[ecumenical council]]s. As a gesture of unity with the East, he caused the traditional text of the Nicene Creed— without the ''filioque''—to be displayed publicly. This text was engraved on two silver tablets at the tomb of [[Saint Peter]].

| + | At a the third synod of Toledo in 589, the ruling [[Visigoths]], who had been [[Arianism|Arian]] [[Christianity|Christians]], submitted to the [[Catholic Church]] and were, thus, obliged to accept the [[Nicene Creed]] with the addition of the ''filioque''. The ''filoque'' was later accepted by the [[Franks]], who, under [[Pippin the Younger]] and his son [[Charlemagne]], rose to dominance in Europe. In the West, the ''filioque'' was thus widely accepted as an integral part of the Nicene Creed and an integral part of the battle against the Arian heresy. |

| | | | |

| − | Later, in [[1014]], the German Emperor Henry II, visited Rome for his coronation and found to his surprise that the Nicene Creed was not used during the Mass. At his request, the Bishop of Rome included the Creed with the ''filioque'', after the reading of the Gospel. This was the first time the phrase was known to be used in the Mass at Rome.

| + | Some westerners, however, demonstrated a sensitivity to eastern concerns that the ''filioque'' represented an innovation that was clearly not part of the received tradition of the [[ecumenical council]]s. In the early ninth century, [[Pope Leo III]] stated that although he personally agreed with the ''filioque,'' he opposed adopting it formally in [[Rome]]. As a gesture of unity with the East, he caused the traditional text of the [[Nicene Creed]]—without the ''filioque''—to be displayed publicly. This text was engraved on two silver tablets at the tomb of [[Saint Peter]]. However, the practice of adding the ''filioque'' was retained in many parts in the West in spite of this papal advice. |

| | | | |

| − | In 1054 the issue contributed significantly to the [[East-West Schism|Great Schism]] of the East and West. | + | ==The Photian schism== |

| | + | In the East, the inclusion of the ''filoque'' clause in western versions of the creed was looked upon with suspicion, especially in view of the fact that the canons of the [[Third Ecumenical Council]] (in Ephesus in 431) specifically forbade and [[anathema]]tized any additions to the [[Nicene Creed]]. The eastern view was that only another ecumenical council could further clarify such issues, and that neither local western councils nor even the pronouncement of a [[pope]] could authorize such a fundamental change. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Later developments==

| + | Meanwhile, in 858, the Byzantine Emperor [[Michael III]] removed [[Patriarch Ignatius I]] as patriarch of [[Constantinople]] for political reasons and replaced him with the future Saint [[Photios]], a layman and noted scholar who had previously been imperial secretary and diplomat. A controversy ensued, and the emperor called a synod to which [[Pope Nicholas I]] was invited to resolve the matter. The pope sent legates to participate in the meeting in 861, which formally confirmed Photios as patriarch. On learning of the council's decision the next year, the [[pope]] was outraged that the synod had not considered Rome's claims to jurisdiction over the newly converted Christians of [[Bulgaria]] and consequently [[excommunication|excommunicated]] his own delegates. He then convened a council in Rome in 863, in which he excommunicated Photios and declared him deposed on the basis that his appointment as patriarch of Constantinople was not canonical. He recognized Ignatius as the legitimate patriarch instead. Thus Rome and Constantinople found themselves, not for the first time in their history, in [[schism]]. |

| − | In the thirteenth century, [[Thomas Aquinas]], [[O.P.]], was one of the dominant Scholastic theologians. He dealt explicitly with the processions of the divine persons in his ''[[Summa Theologica]]''. Following [[John Damascene]], Cyril of Alexandria, and many other Eastern Fathers, he taught that it is proper to speak of the Spirit as proceeding "through the Son" (per Filium), but he also acknowledged the orthodoxy of the filioque. Using Augustinian language, he also speaks of the Father as the ultimate principle (cause or source) of the deity.

| |

| | | | |

| − | In 1274, the [[Second Council of Lyons]] said that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son, in accord with the ''filioque'' in the contemporary Latin version of the Nicene Creed. Reconciliation with the East, through this council, did not last. Remembering the [[Fourth crusade|crusader's sack of Constantinople]] in [[1204]], most Byzantine Christians did not want to be reconciled with the West. In 1283, Patriarch [[John Beccus]], who supported reconciliation with the Latin Church, was forced to abdicate; reunion failed.

| + | The ''filioque'' entered the controversy in 867, when Photius formally rejected the pope's claims and cited the ''filioque'' as proof that Rome had a habit of overstepping its proper limits not only in matters of church discipline but also in [[theology]]. A council was convened with over a thousand clergymen attending. This synod excommunicated Pope Nicholas and condemned his claims of papal primacy, his interference in the newly converted churches of Bulgaria, and the innovative addition of the ''filioque'' clause to the western version of the Nicene Creed. The ''filioque'' was now formally considered by the Eastern church to be a [[heresy]]. |

| | | | |

| − | The aforementioned crusaders had earlier been excommunicated for attacking other Christians (the town of [[Zadar#History|Zara]]). In [[1204]], they became embroiled in local Byzantine politics involving a certain claimant to the throne, and ultimately sacked Constantinople and completely destroyed the Byzantine Empire [for a time] before returning home without ever setting foot on Muslim soil. Pope [[Innocent III]] had sent the Crusaders a letter, forbidding them to attack Constantinople; after hearing of the sack of the city, he lamented their action and disowned them. Nevertheless, the people of Constantinople had a deep hatred for the people they called the "Latins." | + | The murder of Emperor Michael by the usurper [[Basil the Macedonian]], in 867, resulted in the actual deposition of Photios and the re-installation of Ignatius. On the death of Ignatius in October 877, Photius again resumed office, having been recommended by Ignatius prior to his death. He was forced to resign in 886 when [[Leo VI]] took over as emperor and Photius spent the rest of his life as a [[monk]] in exile in [[Armenia]]. He is revered by the [[Eastern Orthodox Church]] today as a major [[saint]]. |

| | | | |

| − | For much of the fourteenth century, there were two bishops, each claiming to be Pope, each excommunicating the other. The [[Western Schism]] was ultimately resolved at the [[Council of Constance]], but in the meantime the East could hardly seek reconciliation with a Western Church divided among itself. In the middle of the century, about a third of Western Europe died of the [[Black Death]]. People were more concerned about the plague than about Church unity.

| + | ==Further East-West controversy== |

| | + | [[Image:Pope Leo IX.jpg|thumb|[[Pope Leo IX]]]] |

| | + | In 1014, the German [[Emperor Henry II]] visited [[Rome]] for his coronation and found to his surprise that the [[Nicene Creed]] was not used during the [[Mass]]. At his request, the pope, [[Benedict VIII]] included the creed, which was read with the ''filioque'' after the reading of the [[Gospel]]. This seems to be the first time the phrase was used in the Mass at Rome. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Failing efforts to reunite East and West===

| + | In 1054, the issue contributed significantly to the [[East-West Schism|Great Schism]] of the East and West, when [[Pope Leo IX]] included the term in his official expression of faith, and the Catholic and Orthodox churches each declared the other guilty of [[heresy]] for including, or not including, the ''filioque'' in their respective creeds. |

| − | At the [[Council of Florence]], in the fifteenth century, Byzantine Emperor [[John VIII Palaeologus]], Bishop Joseph, Patriarch of Constantinople and other bishops from the East travelled to northern Italy, in hope of reconciliation with the West and the aid of Roman armies in their conflict with the [[Ottoman Empire]].

| |

| | | | |

| − | After extensive discussion, in Ferrara, then in Florence, they acknowledged that some Latin Fathers spoke of the procession of the Spirit differently from the Greek Fathers. Since the consensus of the Fathers was held to be reliable, as a witness to common faith, and since the Byzantine Empire desperately needed the military aid of the West, the Western usage was held not to be a heresy and not a barrier to restoration of full communion. All but one of the Orthodox bishops present, [[Mark of Ephesus]], agreed and signed a decree of union between East and West, ''Laetentur Coeli'' in 1439. Mark refused to sign on the grounds that Rome was in both [[heresy]] and [[Schism (religion)|schism]] as a result of its acceptance of the ''filioque'' and the papal claims of universal jurisdiction over the [[Church]]. For his stand, Mark is now venerated as a Saint in [[Eastern Orthodoxy]] and is often honored as a pillar of Orthodoxy.

| + | In 1274, at the [[Second Council of Lyons]], the [[Catholic Church]] officially condemned those who "presume to deny" that the [[Holy Spirit]] proceeds from the Father and the Son. |

| | | | |

| − | Now briefly, officially and publicly, the Catholic and Orthodox Churches were in communion. So, the Council of Florence helped establish a fundamental principle: the Church must be one in its faith, its essential beliefs, but may be diverse in its culture, customs and rites. Although theologically the Church had to be uniform, the addition of the Filioque did not seem at the time to violate that uniformity.

| + | ===Council of Florence=== |

| | + | At the [[Council of Florence]] in the fifteenth century, Byzantine Emperor [[John VIII Palaeologus]], Patriarch Joseph of [[Constantinople]], and other [[bishop]]s from the East traveled to northern [[Italy]] in hope of gaining reconciliation with the West and the aid of Roman armies in their conflict with the [[Ottoman Empire]]. |

| | | | |

| − | However, the reconciliation achieved at Florence was soon destroyed. Many Orthodox faithful and bishops, including the Patriarch of Constantinople, rejected the union, and would not ratify it. The emperor indeed had wished to secure the support of the West in the face of the Ottoman danger, and had pressured some Eastern bishops to sign. To many in the East, the agreement of Florence seemed to be an imposition of Scholastic theology and a desperate plea for help.

| + | After extensive discussion, they acknowledged that some early Latin [[Church Fathers]] indeed spoke of the procession of the Spirit differently from the Greek Fathers. They further admitted that the ''filioque'' was not a [[heresy]] and and should no longer be a barrier to restoration of full communion between the Roman and eastern churches. All but one of the Orthodox bishops present, [[Mark of Ephesus]], agreed to these propositions and signed a decree of union between East and West in 1439. |

| | | | |

| − | The promised Western armies were too late to prevent the [[Fall of Constantinople]] to the Turks in 1453. From that time onward, the Turks fostered separation from the West, which remained an adversary to Islamic political and military dominance. The Patriarch of Constantinople now had to carry out the will of his Muslim overlord; the Church was no longer free.

| + | For a brief period, the Catholic and Orthodox churches were once again in [[communion]] with each other. However, the reconciliation achieved at Florence was soon destroyed. Many Orthodox faithful and bishops rejected the union and would not ratify it, seeing it as a compromise of theological principle in the interest of political expediency. Moreover, the promised Western armies were too late to prevent the [[Fall of Constantinople]] to the Turks in 1453. For his stand against the ''filioque'' and papal supremacy, Mark of Ephesus came to be venerated as a saint in the [[Eastern Orthodox Church]] and is often honored as a pillar of Orthodoxy. |

| − |

| |

| − | Although the ''filioque'' controversy had been officially resolved for both Orthodox and Catholic, (partly because of the historical situation) the resolution at Florence was neither fully received nor permanently sustained.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Eastern Orthodox Church== | + | ==Recent discussions and statements== |

| − | To this day, the [[Eastern Orthodoxy|Orthodox Church]] uses the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed of 381 without the ''filioque''. Many times, the Eastern Churches have rejected the phrase as an unauthorized interpolation, an example of what they consider to be Western hubris. Even more, they objected to the teaching it expressed, as conflicting with biblical and accepted doctrine. They said that for the Holy Spirit to proceed from the Father and the Son there would have to be two sources in the deity, whereas in the one God there can only be one source of divinity or deity.

| + | In the recent past, many Catholic theologians have written on the ''filioque'' with an ecumenical intention. [[Yves Congar]], for example, has argued that the varying formulations regarding the Holy Spirit may be viewed not contradictory but as complementary. Irenee Dalmais likewise points out that East and West have different, yet complementary, theologies of the Holy Spirit. [[Avery Dulles]] traces the history of the ''filioque'' controversy and weighs pros and cons of several possibilities for reconciliation. |

| − | | |

| − | Western theologians anticipated this objection by saying the Spirit proceeds from the Father and Son "as from one principle." The East, however, again objected that this formulation would merge and confuse the persons of the Father and the Son. It was also pointed out that if Father and Son are sources of deity (and only the Holy Spirit is not), it follows that the status of the Spirit is diminished, relative to the Father and the Son, by excluding the Spirit alone as a source of divinity, making the Spirit, rather, a recipient of it — as if the Son and Spirit were both subordinate in their own doctrine. Finally, if one says that the divine essence itself is the source of deity in God, which they took the Latin theologians to say, then (as the Eastern theologians pointed out) another problem is created, a suggestion that the Holy Spirit proceeds from himself, since he is certainly not separate from the divine essence. (By the same reasoning, the Father and Son would also proceed from Themselves. The typical Eastern approach to Triadology avoids this problem by starting with Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and considering that the unique divine Essence is the ''content'' of these Three, rather than that the Three "proceed" from the Essence.)

| |

| − | | |

| − | Both [[Photius I of Constantinople|Patriarch Photius]] in 862 and [[Patriarch Cerularius]] in 1054 accused the West of heresy for introducing the ''filioque'' in the Creed. In general, except for reconciliatory pauses in 1274 and 1439, at the [[Second Council of Lyons]] and the [[Council of Florence]], many Orthodox have repeated the charge of heresy, up to the present day. On the other hand, from the thirteenth century, other Orthodox have pointed out that no ecumenical council ever condemned the entire Western Church and excommunicated its members. Hence, they argued, Latins should not be denied Communion because of the ''filioque'' in their Creed.

| |

| − | | |

| − | An Orthodox Patriarch of Constantinople, [[Patriarch Gregory II of Constantinople|Gregory II]], of Cyprus (1241–1290), proposed a different formula which has also been considered as an Orthodox "answer" to the ''filioque'', though it does not have the status of official Orthodox doctrine. Gregory spoke of an eternal ''manifestation'' of the Spirit by the Son. In other words, he held that the Son eternally manifests (shows forth) the Holy Spirit.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In general, even up to the time of the Council of Florence, the writings of Latin fathers were not widely read in the East; the language was not understood. Hence, the formulation of the ''filioque'', let alone its meaning, was not readily understood in the East. Up to the present, some Western practices are still condemned as heresy by some in the East, disciplinary customs such as mandatory celibacy for priests or the use of pouring water for baptism, rather than triple immersion. When the Pope of Rome visited Greece, some clergy refused to pray with him; others protested publicly against his visit. In Ukraine, when he visited, one Orthodox community held a ceremony of "cursing" for a bishop they considered a heretic. Some Orthodox, too, speak of what they call the "heresy of ecumenism." The Patriarch of Constantinople has accused some monks of Mount Athos, Greece, as being schismatic in spirit, because they consider the entire West to be mired in heresy. Again and again, the ''filioque'' is brought up as the first example of heresy.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In the recent past, however, several Orthodox theologians have considered the ''filioque'' anew, with a view to reconciliation of East and West. Theodore Stylianopoulos, for one, provides an extensive, scholarly overview of the contemporary discussion. A "Father Chrysostom", following Jean-Miguel Garrigues, appeals for common prayer, instead of polemicism. Twenty years after first writing ''The Orthodox Church'', [[Timothy Ware|Bishop Kallistos of Diokleia]] says that he has changed his mind; now, he considers the ''filioque'' dispute to be primarily semantic.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The Moscow patriarchate has said that it does not rebaptize or even chrismate Catholics who become Orthodox; they simply repent and are welcomed. Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople has said that all that is necessary is resolution of what he calls the "[[Uniate]]" problem. Should the conflict over [[Eastern Rite Catholic Churches]] in Russia be resolved, the ''filioque'' dispute would perhaps not be an obstacle to full reconciliation. For many Orthodox, then, the ''filioque'', while still a matter of conflict, would not impede full communion of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Roman Catholic Church==

| |

| − | In 1274, at the Second Council of Lyons, the Catholic Church condemned those who "presume to deny" that the Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son. In the recent past, many Catholic theologians have written on the ''filioque'', with an ecumenical intention. [[Yves Congar]], [[Dominican Order|O.P.]], argues that varying formulations may be seen not as contradictory but as complementary. Irenee Dalmais, O.P. points out that East and West have different, yet complementary, pneumatologies, theologies of the Holy Spirit. [[Avery Dulles]], [[Society of Jesus|S.J.]], traces the history of the ''filioque'' controversy and weighs pros and cons of several possibilities for reconciliation. Eugene Webb makes use of the pneumatology of [[Bernard Lonergan]], S.J.

| |

| − | | |

| − | From an official standpoint, the [[Roman Catholic Church]] has not imposed the recitation of the ''filioque'' on the East. The Eastern Rite Churches of the Catholic Church include, for example, the [[Maronite]]s, the [[Melkite]]s, and the [[Ruthenian Catholic Church|Ruthenians]]. Those who returned to union with the [[Papacy]] at various dates were not required to include the "and the Son" formula in their recitation of the Creed. The Maronites, who claim to have never been out of communion with Rome (though this claim is disputed), have also never used the ''filioque''. Nonetheless, its conciliar definition makes it ''de fide'' for all claiming communion with the faith of Rome.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In many liturgies, when celebrating with bishops from the East, the Pope has recited the [[Nicene Creed]] without the ''filioque''. It is certain that [[Pope Paul VI]] and [[Pope John Paul II]] regard the text of 381 to be entirely correct on its own merit and that using ''filioque'' in Eastern liturgies would not even be appropriate.

| |

| − | | |

| − | Of special importance is a recent clarification of the ''filioque'' by the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity. This document was prepared at the specific request of the Bishop of Rome. It is entitled ''The Greek and Latin Traditions Regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit''<ref name = "EWTN">[http://www.ewtn.com/library/CURIA/PCCUFILQ.HTM]</ref>.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Overview==

| |

| − | In part, the ''filioque'' was originally proposed in order to stress more clearly the connection between the Son and the Spirit, amid a heresy in which the Son was taken as less than the Father because he does not serve as a source of the Holy Spirit. In other words, when the ''filioque'' came into use in Spain and Gaul in the West, they were not aware that their language of procession would not translate well back into the Greek. Conversely, from Photius to the Council of Florence, the Latin Fathers were also not acquainted with the linguistic issues.

| |

| − | | |

| − | To be more specific, the origins of the ''filioque'' in the West are to be found in the writings of certain Church Fathers in the West and especially in the anti-Arian situation of [[7th-century]] Spain. In this context, the ''filioque'' was a means to affirm the full divinity of both the Spirit and the Son. It is not just a question of establishing a connection with the Father and his divinity; it is a question of reinforcing the profession of Catholic faith in the fact that both the Son and Spirit share the fullness of God's nature.

| |

| | | | |

| − | It is ironic that a similar anti-Arian emphasis also strongly influenced the development of the liturgy in the East, for example, in promoting prayer to "Christ Our God," an expression which also came to find a place in the West. (As Joseph Jungmann, S.J., has shown, this shift in mentality caused a loss in appreciation of the mediating role of Christ in the liturgy, as well as other changes in piety.)

| + | Several Orthodox theologians have also considered the ''filioque'' anew, with a view to reconciliation of East and West. [[Theodore Stylianopoulos]], for one, provides an extensive, scholarly overview of the contemporary discussion. Bishop [[Kallistos of Diokleia]] says that he now considers the ''filioque'' dispute to be primarily semantic rather than substantive. Patriarch [[Bartholomew I]] of Constantinople has said that all that is necessary for complete reconciliation is resolution of what he calls the "Uniate" problem, the issue of [[Eastern Rite Catholic Churches]] in the former Soviet countries. For many Orthodox Christians, the ''filioque,'' while still a matter of needing discussion, no longer impedes full [[communion]] between the Catholic and Orthodox Churches. |

| | | | |

| − | In this case, a common adversary, namely, [[Arianism]], had profound, far-reaching effects, in the orthodox reaction in both East and West. It should be noted that the Nicene Creed was not introduced into the celebration of the Mass in Rome until the eleventh century; in this respect, in terms of the Roman liturgy, ''filioque'' is a relatively late addition.

| + | [[Image:BentoXVI-15-10052007.jpg|thumb|Pope Benedict XVI.]] |

| | | | |

| − | As noted, Church politics, authority conflicts, ethnic hostility, linguistic misunderstanding, personal rivalry, and secular motives all combined in various ways to divide East and West. More than once, the ''filioque'' dispute was used to reinforce such division. Now, with a growing spirit of charity, in accord with the will of Christ, that there be one flock (Jn 10:16; 17:22), perhaps the ''filioque'' dispute will be resolved, so that the Catholic and the Orthodox Churches may be reconciled.

| + | An official [[Roman Catholic]] document published on August 6, 2000, and written by the future [[Pope Benedict XVI]] when he was [[Cardinal (Catholicism) |Cardinal]] Joseph Ratzinger—titled ''[[Dominus Iesus]],'' and subtitled ''On the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church''—quietly leaves out the ''filioque'' clause from the Creed without notice or comment. In liturgical celebrations together with bishops from the East, the [[pope]] has recited the [[Nicene Creed]] without the ''filioque''. |

| | | | |

| − | ==Recent discussions and statements==

| + | The ''filioque'' clause was the main subject discussed at the meeting of the [[North American Orthodox-Catholic Theological Consultation]], which met at the Hellenic College/[[Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology]] in [[Brookline, Massachusetts|Brookline]] from June 3 through June 5, 2002. These discussions characterized the ''filioque'' issue as what the Greeks call a ''theologoumenon,'' a theological idea which is open to discussion and is not deemed heretical. Further progress along these lines was made on October 25, 2003, in a document titled ''The Filioque: A Church-Dividing Issue?'' which provides an extensive review of Scripture, history, and theology of the ''filioque'' question. Among its conclusion were: |

| − | Dialogue on this and other subjects is continuing.

| + | *That, in the future, Orthodox and Catholics should refrain from labeling as heretical each other's traditions on the subject of the procession of the Holy Spirit. |

| | + | *That the Catholic Church should declare that the condemnation made at the [[Second Council of Lyons]] (1274) of those "who presume to deny that the Holy Spirit proceeds eternally from the Father and the Son" is no longer applicable. |

| | | | |

| − | A little-known sign of shifting [[Roman Catholic]] policy in the ongoing story of this controversy can be found in an official [[Roman Catholic]] document published on [[August 6]], [[2000]] and written by [[Pope Benedict XVI]], when he was [[Cardinal (Catholicism) |Cardinal]] Joseph Ratzinger, [[prefect]] of the [[Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith]], and assisted by the Congregation's then secretary, [[Tarcisio Cardinal Bertone|Tarcisio Bertone]]. This document, ''[[Dominus Iesus]]'', ([[Latin]] for "Lord Jesus"), and subtitled ''"On the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church"'' contains a remarkable gesture, as in the official [[Latin]] text of this document<ref name = "Vatican">[http://www.vatican.va/roman_curia/congregations/cfaith/documents/rc_con_cfaith_doc_20000806_dominus-iesus_lt.html Dominus Iesus].</ref> (second paragraph in the first section), the ''filioque'' clause is quietly left out without notice or comment. Was this removal an attempt to reach a hand across the theological and historical chasm separating Eastern and Western Churches? This document takes on increased significance with the elevation of one of its authors from [[cardinal (Catholicism)|cardinal]] to [[pope]].

| + | In the judgment of the consultation, the question of the ''filioque'' is no longer a "Church-dividing" issue. |

| | | | |

| − | The ''filioque'' clause was the main subject discussed at the 62nd meeting of the [[North American Orthodox-Catholic Theological Consultation]], which met at the Hellenic College/[[Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology]] in [[Brookline, Massachusetts|Brookline]] from [[June 3]] through [[June 5]] [[2002]], for their spring session. As a result of these modern discussions, it has been suggested that the Orthodox could accept an "economic" ''filioque'' that states that the Holy Spirit, who originates in the Father alone, was sent to the Church "through the Son" (as the [[Paraclete]]), but this is not official Orthodox doctrine. It is what the Greeks call a ''theologumenon'', a theological idea. (Similarly, the late Edward Kilmartin, S.J., proposed as a ''theologumenon'', a "mission" of the Holy Spirit to the Church.)

| + | ==See also== |

| | + | *[[Great Schism]] |

| | + | *[[Holy Spirit]] |

| | | | |

| − | Recently, an important, agreed statement has been made by the [[North America]]n Orthodox-Catholic Theological Consultation, on [[October 25]], [[2003]]. This document ''The Filioque: A Church-Dividing Issue?'', provides an extensive review of Scripture, history, and theology. Especially critical are the recommendations of this consultation, for example:

| + | ==Notes== |

| − | | + | <references/> |

| − | #That all involved in such dialogue expressly recognize the limitations of our ability to make definitive assertions about the inner life of God.

| |

| − | #That, in the future, because of the progress in mutual understanding that has come about in recent decades, Orthodox and Catholics refrain from labeling as heretical the traditions of the other side on the subject of the procession of the Holy Spirit.

| |

| − | #That Orthodox and Catholic theologians distinguish more clearly between the divinity and hypostatic identity of the Holy Spirit (which is a received dogma of our Churches) and the manner of the Spirit's origin, which still awaits full and final ecumenical resolution.

| |

| − | #That those engaged in dialogue on this issue distinguish, as far as possible, the theological issues of the origin of the Holy Spirit from the ecclesiological issues of primacy and doctrinal authority in the Church, even as we pursue both questions seriously, together.

| |

| − | #That the theological dialogue between our Churches also give careful consideration to the status of later councils held in both our Churches after those seven generally received as ecumenical.

| |

| − | #That the Catholic Church, as a consequence of the normative and irrevocable dogmatic value of the Creed of 381, use the original Greek text alone in making translations of that Creed for catechetical and liturgical use.

| |

| − | #That the Catholic Church, following a growing theological consensus, and in particular the statements made by [[Pope Paul VI]], declare that the condemnation made at the [[Second Council of Lyons]] ([[1274]]) of those "who presume to deny that the Holy Spirit proceeds eternally from the Father and the Son" is no longer applicable.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In the judgment of the consultation, the question of the ''filioque'' is no longer a "Church-dividing" issue, one which would impede full reconciliation and full communion, once again. It is for the bishops of the Catholic and Orthodox Churches to review this work and to make whatever decisions would be appropriate.

| |

| | | | |

| | ==References== | | ==References== |

| − | There is a great deal written on the topic of the ''filioque''; what follows, therefore, is selective. As time goes on, this list will inevitably have to be updated.

| + | * Haugh, Richard S. ''Photius and the Carolingians: The Trinitarian Controversy''. Belmont, Mass: Nordland Pub. Co, 1975. ISBN 978-0913124055. |

| | + | * Kolbaba, Tia M. ''Inventing Latin Heretics: Byzantines and the Filioque in the Ninth Century''. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, 2008. ISBN 978-1580441339. |

| | + | * Küng, Hans, and Jürgen Moltmann. ''Conflicts About the Holy Spirit''. New York: Seabury Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0816420353. |

| | + | * Ngien, Dennis. ''Apologetic for Filioque in Medieval Theology.'' Bletchley, Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2003. ISBN 978-1842272763. |

| | + | * Vischer, Lukas. ''Spirit of God, Spirit of Christ: Ecumenical Reflections on the Filioque Controversy''. Faith and order paper, no. 103. London: SPCK, 1981. ISBN 978-2825406625 |

| | + | {{Nuttall}} |

| | | | |

| − | *"Filioque," '''Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church'''. Oxford, 1997, p. 611.

| + | ==External links== |

| − | *David Bradshaw. '''Aristotle East and West: Metaphysics and the Division of Christendom'''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004, pp. 214–220.

| + | All links retrieved March 26, 2024. |

| − | *John St. H. Gibaut, "The ''Cursus Honorum'' and the Western Case Against Photius," '''Logos''' 37 (1996), 35–73.

| |

| − | *Elizabeth Teresa Groppe. '''Yves Congar's Theology of the Holy Spirit'''. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. See esp. pp. 75–79, for a summary of Congar's work on the ''filioque''. Congar is widely considered the most important Roman Catholic ecclesiologist of the twentieth century. He was influential in the composition of several Vatican II documents. Most important of all, he was instrumental in the association in the West of pneumatology and ecclesiology, a new development.

| |

| − | *Richard Haugh. '''Photius and the Carolingians: The Trinitarian Controversy'''. Belmont, MA: Nordland Publishing Company, 1975.

| |

| − | *Joseph Jungmann, S.J. '''Pastoral Liturgy'''. London: Challoner, 1962. See "Christ our God," pp. 38–48.

| |

| − | *James Likoudis. '''Ending the Byzantine Greek Schism'''. New Rochelle, New York: 1992. An apologetic response to polemical attacks. A useful book for its inclusion of important texts and documents; see especially citations and works by Thomas Aquinas, O.P., Demetrios Kydones, Nikos A. Nissiotis, and Alexis Stawrowsky. The select bibilography is excellent. The author demonstrates that the ''filioque'' dispute is only understood as part of a dispute over papal primacy and cannot be dealt with apart from ecclesiology.

| |

| − | *Bruce D. Marshall, "''''Ex Occidente Lux?'''' Aquinas and Eastern Orthodox Theology," '''Modern Theology''' 20:1 (January, 2004), 23–50. Reconsideration of the views of Aquinas, especially on deification and grace, as well as his Orthodox critics. The author suggests that Aquinas may have a more accurate perspective than his critics, on the systematic questions of theology that relate to the ''filioque'' dispute.

| |

| − | *John Meyendorff. '''Byzantine Theology'''. New York: Fordham University Press, 1979, pp. 91-94.

| |

| − | *Aristeides Papadakis. '''Crisis in Byzantium: The Filioque Controversy in the Patriarchate of Gregory II of Cyprus (1283–1289)'''. New York: Fordham University Press, 1983.

| |

| − | *Aristeides Papadakis. '''The Christian East and the Rise of the Papacy'''. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1994, pp. 232-238 and 379-408.

| |

| − | *Duncan Reid. '''Energies of the Spirit: Trinitarian Models in Eastern Orthodox and Western Theology'''. Atlanta, Georgia: Scholars Press, 1997.

| |

| − | *A. Edward Siecienski. '''The Use of Maximus the Confessor's Writing on the Filioque at the Council of Ferrara-Florence (1438–1439)'''. Ann Arbor, Michigan: UMI Dissertation Services, 2005.

| |

| − | *Malon H. Smith, III. '''And Taking Bread: Cerularius and the Azyme Controversy of 1054'''. Paris: Beauschesne, 1978. This work is still valuable for understanding cultural and theological estrangement of East and West by the turn of the millennium. Now, it is evident that neither side understood the other; both Greek and Latin antagonists assumed their own practices were normative and authentic.

| |

| − | *Timothy [Kallistos] Ware. '''The Orthodox Church'''. New edition. London: Penguin, 1993, pp. 52–61.

| |

| − | *Timothy [Kallistos] Ware. '''The Orthodox Way'''. Revised edition. Crestwood, New York: 1995, pp. 89–104.

| |

| − | *[World Council of Churches] /Conseil Oecuménique des Eglises. '''La théologie du Saint-Esprit dans le dialogue œcuménique''' Document # 103 [Faith and Order]/Foi et Constitution. Paris: Centurion, 1981.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==External links==

| |

| − | ===General===

| |

| − | *[http://www.scoba.us/resources/filioque-p02.asp Orthodox/Catholic joint statement]

| |

| − | *[http://www.orthodoxwiki.org/Filioque Filioque] at OrthodoxWiki

| |

| | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06073a.htm Catholic Encyclopedia entry] | | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06073a.htm Catholic Encyclopedia entry] |

| − | *[http://www.iclnet.org/pub/resources/text/history/creed.filioque.txt Notes on the Filoque Controversy]

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Historical origins ===

| |

| − | *[http://www.praiseofglory.com/filioque.htm An extensive history of the ''filioque'' dispute, assembled by Gerard Seraphin]. The author makes an important reference to Johannes Grohe, who speaks of Eastern use of the ''filioque''.

| |

| − | *[http://www.unc.edu/~gdemacop/Filioque.html Chronology of the Filioque Controversy]. A one-page overview of the dispute, from 325 to 1453.

| |

| − | *[http://www.romanity.org/htm/rom.03.en.franks_romans_feudalism_and_doctrine.03.htm John S. Romanides, "The Filioque"]. The author shows how Franks in the Carolingian Empire in the ninth century worked in opposition to the ancient Church of Rome-Constantinople, the "Roman Church" of East and West.

| |

| − | *[http://www.stjosephplacentia.org/RCath-L/history6.htm "History of the Mass: Part VI"]. A brief but more objective presentation of the influence of the Franks in matters of discipline.

| |

| − | *[http://www.praiseofglory.com/photius.htm "The Patriarch Photius: The Era of Confrontation and Polemics"]. Yves Congar, O.P., here provides the historical context of the ''filioque'' dispute, as it took place with Patriarch Photius.

| |

| − | *[http://www.geocities.com/trvalentine/orthodox/photius_encyclical.html '''Encyclical to the Eastern Patriarchs''']. The polemical letter of Patriarch Photius, condemning the ''filioque'', as well as other practices, such as fasting on Saturdays. From the very words of Photius, it is evident that the origin of his hostility is in what he perceives as competition from "Westerners" (Latin priests) in Bulgaria, a territory he considers under his jurisdiction. It is also evident, as Photius says, that he never heard of the ''filoque'' until now; in spite of his considerable erudition, he is, therefore, not familiar with the Latin Fathers.

| |

| − | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/12043b.htm "Photius of Constantinople"]. From the '''Catholic Encyclopedia'', an introduction to Photius, reflecting the state of scholarship on this topic at the beginning of the twentieth century.

| |

| − | *[http://www.myriobiblos.gr/texts/english/milton1_16.html "The Patriarch Photius and his disputes with Rome"]. Milton V. Anastos (like Congar, Dvornik et al.) gives a much kinder assessment of Photius. Contemporary scholarship has corrected many false statements about his actions and provided a more accurate historical context. Pope John VIII, for example, never excommunicated Photius.

| |

| − | *[http://www.stpaulsirvine.org/html/TheGreatSchism.htm '''The Orthodox Church''']. In this excerpt from the book, Bishop Kallistos Ware writes of the role of the ''filioque'' in the East-West disputes, especially objections to that phrase by St. Photius and Patriarch Cerularius. The author provides the historical context of the estrangement of East and West; he does an excellent job.

| |

| − | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/0555c.htm "Hugh and Leo Etherianus"]. At Constantinople, in the twelfth century, Hugh Etherianus prepared the first exhaustive and scholarly defense of the ''filioque'', using both Latin and Greek Fathers: '''De haeresibus quas Graeci in Latinos devolvunt, sive quod Spiritus Sanctus ex utroque Patre et Filio procedit'''. In English, that's "About the heresies of which the Greeks accuse the Latins, whether the Holy Spirit proceeeds from both the Father and the Son."

| |

| − | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/14663b.htm "St. Thomas Aquinas"]. Introduction to Thomas Aquinas, O.P., prominent Scholastic theologian and philosopher, defender of the ''filioque''.

| |

| − | *[http://www.logoslibrary.org/aquinas/summa/1027.html Excerpt from the '''Summa Theologica''', "The Processions of the Divine Persons"]. Explicit explanation of the processions of the Trinity, according to Aquinas.

| |

| − | *[http://www.newadvent.org/summa/103602.htm Another excerpt from the '''Summa''', "Whether the Holy Ghost proceeds from the Son?"] The Scholastic perspective of Aquinas, precisely on the topic of this present article.

| |

| − | *[http://www.op.org/steinkerchner/comps/notes/aquinas.html Scott Steinkercher, O.P., "Notes on Thomas Aquinas"]. Background, method, and anthropology of the Scholastic theology of Aquinas.

| |

| − | *[http://www.corpusthomisticum.org/oce.html Thomas Aquinas, '''Contra errores Graecorum''']. This 55-page essay, in Latin, is not for the faint of heart. Alta Vista and Google probably cannot render the text clearly in English, because of the dense logic of the arguments. In this essay, Aquinas argues that the Greeks don't accept universal jurisdiction of the Pope because their pneumatology is defective, as evidenced, he says, in their rejection of the ''filioque''. This essay was influential among the participants in the 1274 Council of Lyons. Pope Urban IV had asked Aquinas to prepare this document, in preparation for that council. Regrettably, there does not seem to be a complete English translation of '''Contra errores''' available online.

| |

| − | *[http://www.globalserve.net/~bumblebee/ecclesia/errorgre.htm '''Contra errores Graecorum''']. This is an English translation of the first part of this essay, by Antoine Valentin. Although the relevant passages are not translated, in this excerpt you can see how Aquinas argues.

| |

| − | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/02380b.htm Patriarch John Beccus of Constantinople]. The remarkable life of this Orthodox bishop; he did not consider the ''filioque'' heresy and favored reconciliation with the West.

| |

| − | *[http://www.geocities.com/trvalentine/orthodox/tomos1285.html ''Tomos'' of 1285]. The definitive rejection by [[Patriarch Gregory II of Constantinople|Patriarch Gregory]] and the Council of [[Blachernae]] of the union of 1274 and the preceding patriarch, John Beccus. Calling the ''filioque'' addition to the Creed "blasphemy," this document represents a polemical, violent reaction to Scholastic theology, used to explain and defend the ''filioque''. In this document, Beccus and his followers are said to be banished and "expelled from Orthodoxy."

| |

| − | *[http://www.praiseofglory.com/gilladdition.htm Excerpt from '''The Council of Florence''' by Joseph Gill, S.J., "The Addition to the Creed"]. Dialogue between East and West at Ferrara, on the ''filioque''.

| |

| − | *[http://www.praiseofglory.com/gillprocession.htm Another excerpt from '''The Council of Florence''', "Florence and the Dogmatic Discussions"]. Dialogue at Florence on the ''filioque''.

| |

| − | *[http://www.praiseofglory.com/gillunion.htm A third excerpt from '''The Council of Florence''', "Reunion"]. History and text of '''Laetentur Caeli''', 1439 decree of union between East and West.

| |

| | | | |

| − | === Orthodox Church ===

| |

| − | *[http://www.myriobiblos.gr/texts/english/Dragas_RomanCatholic.html George Dragas, "The Manner of Reception of Roman Catholic Converts into the Orthodox Church"] Tracing the history of such reception, the author makes the important point that the practice of re-baptizing Roman Catholics became widespread in the thirteenth century, after the sacking of Constantinople by the Crusaders. Even single immersion, as in the West, was often considered invalid. In Russia, says the author, such re-baptizing was a universal practice; it must, he says, have been transferred there from the Greek Church. However, a synod in 1484 prescribed only chrismation (anointing), with a renunciation of the ''filioque'' and other Western practices, such as the use of unleavened bread for the Eucharist. In both re-baptism and chrismation, the Latins were treated as heretics undergoing reconciliation.

| |

| − | *[http://www.isidore-of-seville.com/orthodoxy_and_catholicism/5.html Ecumenism and Heresy] Here is a list of links, giving Orthodox positions that are anti-ecumenical and positions that are more irenic in character. See especially the sites with authorship by the Sacred Community of Mount Athos, John Meyendorff, and David Armstrong.

| |

| − | *[http://www.geocities.com/heartland/5654/orthodox/stylianopoulos_filioque.html "The Filioque: Dogma, Theologumenon or Heresy?"] Theodore Stylianopoulos here presents an extensive, scholarly overview of the contemporary discussion of the ''filioque''. His article is carefully reasoned and works toward reconciliation.

| |

| − | *[http://www.goarch.org/en/ourfaith/articles/article8523.asp "Papal Primacy"]. In this article, Emmanuel Clapsis provides a well-documented study of the context in which the ''filioque'' dispute may be resolved: a communion ecclesiology, with a renewed understanding of the primacy of the Bishop of Rome. As Cardinal Ratzinger says, we can return to the understanding of that primacy as it was in the first millennium; that would provide a basis for reconciliation of the Orthodox and Catholic Churches.

| |

| − | *[http://www.cin.org/archives/cineast/199702/0473.html "The True Faith"] Father Chrysostom here appeals for prayer, to resolve long-standing conflict and polemicism.

| |

| − | *[http://www.holytrinitymission.org/books/english/apostolic_christianity_s_kovasevich.htm#_Toc22999842 "Apostolic Christianity and the 23,000 Western Churches - 6. The Great Schism"] Steven Kovacevich details here in [[Q&A]] format the heresies, especially the ''filioque'', that led to the [[East-West Schism|Great Schism]].

| |

| | | | |

| − | === Catholic Church ===

| |

| − | *[http://www.praiseofglory.com/congarfilioque.htm Yves Congar, O.P., '''I Believe in the Holy Spirit''', "Attempts at and Suggestions for an Agreement"]. This renowned theologian says that varying formulations may be seen not as contradictory but as complementary.

| |

| − | *[http://www.praiseofglory.com/spiriteastwest.htm Irenee Dalmais, O.P., "The Spirit of Truth and of Life"]. The author speaks of differing pneumatologies (theologies of the Spirit) in East and West.

| |

| − | *[http://ctsfw.edu/library/files/pb/1232 Avery Dulles, S.J., "The ''Filioque'': What Is at Stake?"]. The author traces the history of the ''filioque'' controversy and evaluates current options. He says that it is important for the East to acknowledge that the West has not been in heresy for the past 1500 years. [[PDF]].

| |

| − | *[http://faculty.washington.edu/ewebb/Pneumatology.pdf Eugene Webb, "The Pneumatology of Bernard Lonergan: A Byzantine Comparison"]. The author uses the pneumatology of Bernard Lonergan, S.J., to resolve the ''filioque'' controversy. PDF.

| |

| − | *[http://www.rtforum.org/lt/lt66.pdf "On the Procession of the Holy Spirit"]. Father John McCarthy of the Roman Theological Forum analyzes what the Filioque means.

| |

| − | *[http://www.geocities.com/trvalentine/orthodox/vatican_clarification.html "The Greek and Latin Traditions regarding the Procession of the Holy Spirit," a clarification from the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity.] A very important document, making a substantial contribution to contemporary theological dialogue, working toward reconciliation.

| |

| − | *[http://www.geocities.com/trvalentine/orthodox/zizioulis_onesource.html Ioannis Zizioulas, "One Single Source: An Orthodox response to the Clarification on the Filioque"]. The author says that East and West can easily continue dialogue on the ''filioque'', provided that both agree that the Father is the sole cause/origin both of the Son and of the Spirit. This article is a positive statement, giving grounds for further progress towards reconciliation.

| |

| − | *[http://www.myriobiblos.gr/texts/french/larchet.html Jean-Claude Larchet, "À propos de la récente « clarification » du conseil pontifical pour la promotion de l'unité des chrétiens]. A 56-page, scholarly response to the clarification of the Pontifical Council, by Jean-Claude Larchet, in French. An extensive, well thought-out analysis.

| |

| − | *[http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/06073a.htm Filioque], from the Robert Appleton Company's Catholic Encyclopedia, provided online by New Advent. A relatively brief Catholic synopsis of the ''filioque'' controversy.

| |

| − | *[http://www.catholic.com/library/Filioque.asp Filioque], from the Catholic Answers library]. A very brief Catholic synopsis and apology of the ''filioque'' controversy.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Overview ===

| |

| − | *[http://www.booksite.com/texis/scripts/pubsite/showdetail.html?sid=4460&isbn=0915866455 Excerpt from '''The Mass of the Roman Rite'''] Here, Joseph Jungmann, S.J., explains the importance of the mediating role of Christ in the liturgy, largely lost in the East, because of anti-Arianism, the same reactive force that in Spain gave rise to the ''filioque''.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | === Recent discussions and statements ===

| |

| − | *[http://www.usccb.org/seia/filioque.htm The agreed statement of the North American Orthodox-Catholic Theological Consulation, [[25 October]] [[2003]].] A very important document, with objective, historical accounting and critical recommendations, to promote ultimate reconciliation between East and West, on the ''filioque'' dispute.

| |

| − | *[http://www.tcrnews2.com/Orthodox_Catholic.html "The Catholic-Orthodox Dialogue: Lights and Shadows"] Catholic James Likoudis, an ex-Orthodox polemicist, here provides a record of some responses to the 2003 agreed statement.

| |

| − |

| |

| − | {{Nuttall}}

| |

| | | | |

| | [[Category: Philosophy and religion]] | | [[Category: Philosophy and religion]] |

| | [[Category: Religion]] | | [[Category: Religion]] |

| | + | [[Category:Christianity]] |

| | + | [[Category:history]] |

| | | | |

| | {{Credit|102032188}} | | {{Credit|102032188}} |

A diagram of the so-called "Shield Trinity" in which the

Holy Spirit seems to "proceed" from both the Father and the Son, in conformity with the notion of the

filioque clause.

The filioque clause is a heavily disputed part of Christian trinitarian theology and one of the core differences between Catholic and Orthodox traditions. The Latin term filioque means "and [from] the son," referring to whether the Holy Spirit "proceeds" from the Father alone or both from the Father and the Son. In the Orthodox tradition, the Nicene Creed reads, "We believe in the Holy Spirit … who proceeds from the Father," while in the Catholic tradition it reads "We believe in the Holy Spirit… who proceeds from the Father and the Son." The Orthodox position is based on the tradition of the ecumenical councils, which specify "from the Father" only. The Catholic position is based on longstanding traditions of the western Church Fathers, local councils, and several popes.

Underlying the theological question were issues such as the struggle for supremacy between Rome and Constantinople and the right of the pope to determine the expression of the Creed. The western churches, meanwhile, had used the filioque clause in part to exclude Christians in western Europe who were suspected of sympathizing with Arianism (a view that introduced sequence into Christian trinitarianism). The filioque controversy emerged as a major issue during the so-called Photian schism of the seventh century and later became one of the causes of the Great Schism of 1054, which created a lasting break between the Catholic and Orthodox faiths.

As with many such theological conflicts, many Christians today no longer see the issue as something which should keep them apart, and in recent decades Catholic and Orthodox leaders have made important steps toward reconciling on this and other matters that divide them.

Background

Shield Trinity diagram in which the

Holy Spirit seems to proceed directly from the Father.

The roots of the filioque controversy may be found in the differing traditions between eastern and western Christian approaches to the expression of trinitarian theology. The Council of Nicea, in 325 C.E., also known as the First Ecumenical Council, affirmed a belief in the Trinity, but was concerned primarily with the relationship between God the Father and God the Son. It did not deal directly with the question of the Holy Spirit's relationship to the Father and the Son. Its creed simply stated, "We believe in the Holy Spirit."

In 381, the First Council of Constantinople, also known as the Second Ecumenical Council, addressed the issue of the Holy Spirit more directly. On the basis of John 15:26b—"I will send to you from the Father, the Spirit of truth who goes out from the Father, he will testify about me"—it modified Nicea's creed by stating that the Holy Spirit "proceeds from the Father." This creed was confirmed at the Council of Chalcedon in 451 C.E.

The filioque controversy was exacerbated by the long-standing struggle between Rome and Constantinople for supremacy over the Christian churches in the later Roman Empire. This contest also played a role in several other theological battles, from the Arian controversy to the struggles over Nestorianism (a view that Christ consisted of two distinct natures) and Monophysitism (a view that Christ has only one nature), the so-called Meletian schism, the Three Chapters controversy, and the battles over Iconoclasm. Even the elections of several popes became hotly contested, sometimes violent struggles between one party which leaned more toward the Roman emperors in Constantinople and an opposing faction which supported the "barbarian" kings who often controlled Italy and the West.

Origins of the filioque

The aforementioned councils were all considered "ecumenical" and, therefore, binding on all orthodox Christians. In the West, however, Saint Augustine of Hippo followed Tertullian and Ambrose in teaching that the Holy Spirit proceeded from the Father and the Son, though subordinate to neither. Other Latin Church Fathers also spoke of the Spirit proceeding from both the Father and the Son. While familiar in the West, however, this way of speaking was virtually unknown among the ancient churches of the Greek-speaking Eastern Roman Empire. (However, a regional council in Persia, in 410, introduced one of the earliest forms of the filioque in its version the creed, specifying that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father "and from the Son.")

The first Latin council to add the phrase and the Son (filioque) to its creed was the Synod of Toledo in Spain in 447. The formula was also used in a letter from Pope Leo I to the members of that synod. The addition came about in opposition to fifth century manifestations of a form the Arian "heresy" which was prevalent among the Germanic tribes of Europe. By affirming the Holy Spirit's procession from both the Father and the Son, the bishops at Toledo intended to exclude Arian notions that the Son was something less than a co-eternal and equal partner with the Father from the very beginning of existence.

At a the third synod of Toledo in 589, the ruling Visigoths, who had been Arian Christians, submitted to the Catholic Church and were, thus, obliged to accept the Nicene Creed with the addition of the filioque. The filoque was later accepted by the Franks, who, under Pippin the Younger and his son Charlemagne, rose to dominance in Europe. In the West, the filioque was thus widely accepted as an integral part of the Nicene Creed and an integral part of the battle against the Arian heresy.

Some westerners, however, demonstrated a sensitivity to eastern concerns that the filioque represented an innovation that was clearly not part of the received tradition of the ecumenical councils. In the early ninth century, Pope Leo III stated that although he personally agreed with the filioque, he opposed adopting it formally in Rome. As a gesture of unity with the East, he caused the traditional text of the Nicene Creed—without the filioque—to be displayed publicly. This text was engraved on two silver tablets at the tomb of Saint Peter. However, the practice of adding the filioque was retained in many parts in the West in spite of this papal advice.

The Photian schism

In the East, the inclusion of the filoque clause in western versions of the creed was looked upon with suspicion, especially in view of the fact that the canons of the Third Ecumenical Council (in Ephesus in 431) specifically forbade and anathematized any additions to the Nicene Creed. The eastern view was that only another ecumenical council could further clarify such issues, and that neither local western councils nor even the pronouncement of a pope could authorize such a fundamental change.

Meanwhile, in 858, the Byzantine Emperor Michael III removed Patriarch Ignatius I as patriarch of Constantinople for political reasons and replaced him with the future Saint Photios, a layman and noted scholar who had previously been imperial secretary and diplomat. A controversy ensued, and the emperor called a synod to which Pope Nicholas I was invited to resolve the matter. The pope sent legates to participate in the meeting in 861, which formally confirmed Photios as patriarch. On learning of the council's decision the next year, the pope was outraged that the synod had not considered Rome's claims to jurisdiction over the newly converted Christians of Bulgaria and consequently excommunicated his own delegates. He then convened a council in Rome in 863, in which he excommunicated Photios and declared him deposed on the basis that his appointment as patriarch of Constantinople was not canonical. He recognized Ignatius as the legitimate patriarch instead. Thus Rome and Constantinople found themselves, not for the first time in their history, in schism.

The filioque entered the controversy in 867, when Photius formally rejected the pope's claims and cited the filioque as proof that Rome had a habit of overstepping its proper limits not only in matters of church discipline but also in theology. A council was convened with over a thousand clergymen attending. This synod excommunicated Pope Nicholas and condemned his claims of papal primacy, his interference in the newly converted churches of Bulgaria, and the innovative addition of the filioque clause to the western version of the Nicene Creed. The filioque was now formally considered by the Eastern church to be a heresy.

The murder of Emperor Michael by the usurper Basil the Macedonian, in 867, resulted in the actual deposition of Photios and the re-installation of Ignatius. On the death of Ignatius in October 877, Photius again resumed office, having been recommended by Ignatius prior to his death. He was forced to resign in 886 when Leo VI took over as emperor and Photius spent the rest of his life as a monk in exile in Armenia. He is revered by the Eastern Orthodox Church today as a major saint.

Further East-West controversy

In 1014, the German Emperor Henry II visited Rome for his coronation and found to his surprise that the Nicene Creed was not used during the Mass. At his request, the pope, Benedict VIII included the creed, which was read with the filioque after the reading of the Gospel. This seems to be the first time the phrase was used in the Mass at Rome.

In 1054, the issue contributed significantly to the Great Schism of the East and West, when Pope Leo IX included the term in his official expression of faith, and the Catholic and Orthodox churches each declared the other guilty of heresy for including, or not including, the filioque in their respective creeds.

In 1274, at the Second Council of Lyons, the Catholic Church officially condemned those who "presume to deny" that the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father and the Son.

Council of Florence

At the Council of Florence in the fifteenth century, Byzantine Emperor John VIII Palaeologus, Patriarch Joseph of Constantinople, and other bishops from the East traveled to northern Italy in hope of gaining reconciliation with the West and the aid of Roman armies in their conflict with the Ottoman Empire.

After extensive discussion, they acknowledged that some early Latin Church Fathers indeed spoke of the procession of the Spirit differently from the Greek Fathers. They further admitted that the filioque was not a heresy and and should no longer be a barrier to restoration of full communion between the Roman and eastern churches. All but one of the Orthodox bishops present, Mark of Ephesus, agreed to these propositions and signed a decree of union between East and West in 1439.

For a brief period, the Catholic and Orthodox churches were once again in communion with each other. However, the reconciliation achieved at Florence was soon destroyed. Many Orthodox faithful and bishops rejected the union and would not ratify it, seeing it as a compromise of theological principle in the interest of political expediency. Moreover, the promised Western armies were too late to prevent the Fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453. For his stand against the filioque and papal supremacy, Mark of Ephesus came to be venerated as a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and is often honored as a pillar of Orthodoxy.

Recent discussions and statements

In the recent past, many Catholic theologians have written on the filioque with an ecumenical intention. Yves Congar, for example, has argued that the varying formulations regarding the Holy Spirit may be viewed not contradictory but as complementary. Irenee Dalmais likewise points out that East and West have different, yet complementary, theologies of the Holy Spirit. Avery Dulles traces the history of the filioque controversy and weighs pros and cons of several possibilities for reconciliation.

Several Orthodox theologians have also considered the filioque anew, with a view to reconciliation of East and West. Theodore Stylianopoulos, for one, provides an extensive, scholarly overview of the contemporary discussion. Bishop Kallistos of Diokleia says that he now considers the filioque dispute to be primarily semantic rather than substantive. Patriarch Bartholomew I of Constantinople has said that all that is necessary for complete reconciliation is resolution of what he calls the "Uniate" problem, the issue of Eastern Rite Catholic Churches in the former Soviet countries. For many Orthodox Christians, the filioque, while still a matter of needing discussion, no longer impedes full communion between the Catholic and Orthodox Churches.

An official Roman Catholic document published on August 6, 2000, and written by the future Pope Benedict XVI when he was Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger—titled Dominus Iesus, and subtitled On the Unicity and Salvific Universality of Jesus Christ and the Church—quietly leaves out the filioque clause from the Creed without notice or comment. In liturgical celebrations together with bishops from the East, the pope has recited the Nicene Creed without the filioque.

The filioque clause was the main subject discussed at the meeting of the North American Orthodox-Catholic Theological Consultation, which met at the Hellenic College/Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology in Brookline from June 3 through June 5, 2002. These discussions characterized the filioque issue as what the Greeks call a theologoumenon, a theological idea which is open to discussion and is not deemed heretical. Further progress along these lines was made on October 25, 2003, in a document titled The Filioque: A Church-Dividing Issue? which provides an extensive review of Scripture, history, and theology of the filioque question. Among its conclusion were:

- That, in the future, Orthodox and Catholics should refrain from labeling as heretical each other's traditions on the subject of the procession of the Holy Spirit.

- That the Catholic Church should declare that the condemnation made at the Second Council of Lyons (1274) of those "who presume to deny that the Holy Spirit proceeds eternally from the Father and the Son" is no longer applicable.

In the judgment of the consultation, the question of the filioque is no longer a "Church-dividing" issue.

See also

Notes

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Haugh, Richard S. Photius and the Carolingians: The Trinitarian Controversy. Belmont, Mass: Nordland Pub. Co, 1975. ISBN 978-0913124055.

- Kolbaba, Tia M. Inventing Latin Heretics: Byzantines and the Filioque in the Ninth Century. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, 2008. ISBN 978-1580441339.

- Küng, Hans, and Jürgen Moltmann. Conflicts About the Holy Spirit. New York: Seabury Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0816420353.

- Ngien, Dennis. Apologetic for Filioque in Medieval Theology. Bletchley, Milton Keynes: Paternoster, 2003. ISBN 978-1842272763.

- Vischer, Lukas. Spirit of God, Spirit of Christ: Ecumenical Reflections on the Filioque Controversy. Faith and order paper, no. 103. London: SPCK, 1981. ISBN 978-2825406625

This article incorporates text from the public domain 1907 edition of The Nuttall Encyclopædia.

External links

All links retrieved March 26, 2024.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article

in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.