Ernst Haeckel

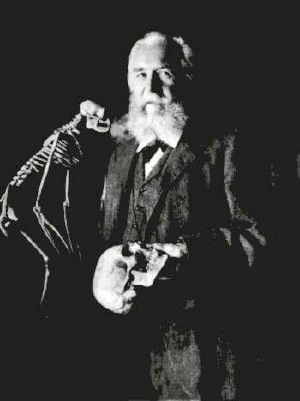

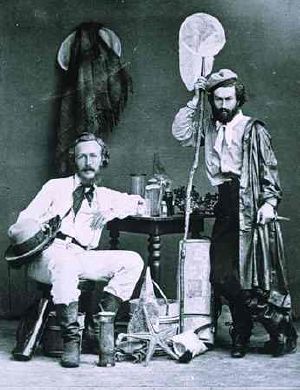

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (February 16, 1834 — August 9, 1919), also written von Haeckel, was an eminent German zoologist best known as an early promoter and popularizer of Charles Darwin's evolutionary theory.

Influenced by Darwin's ideas, Haeckel developed the controversial "recapitulation theory," which claims that an individual organism's biological development, or ontogeny, parallels in brief the entire evolutionary development of its species, or phylogeny. That is, according to Haeckel's formulation: "Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny". His concept of recapitulation has been discredited its absolute form (now called "strong recapitulation"), although recognized as being perhaps partly fruitful.

Haeckel embraced evolution not only as a scientific theory, but as a world-view. He extrapolated a new religion or philosophy called "monism" from evolutionary science, which cast evolution as a cosmic force, a manifestation of the creative energy of nature. A proponent of social Darwinism, Haekel was increasingly involved in elaborating the social, political, and religious implications of Darwinism in the 1880s and 1890s; his writings and lectures on monism were later used to provide pseudo-scientific justifications for racist and nationalist programs of National Socialism in 1930s Germany.

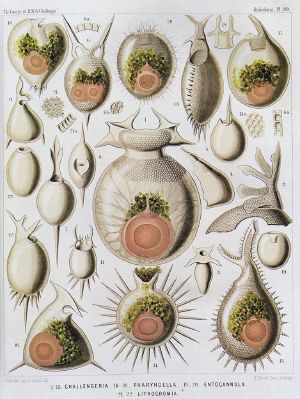

As a professor of comparative anatomy at the University of Jena, Haeckel specialized in invertebrate anatomy, doing his most important work on radiolaria, a type of protozoan zooplankton found throughout the ocean. Heackel named thousands of new species, mapped a genealogical tree relating all life forms, and coined many now ubiquitous terms in biology, including phylum, phylogeny and ecology. He also discovered many species in the kingdom that he named Protista.

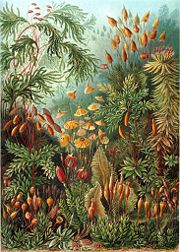

Haeckel’s chief interests lay in evolution and life development processes in general, including development of nonrandom form, which culminated in the beautifully illustrated Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms of Nature), a collection of 100 detailed, multi-color illustrations of animals and sea creatures.

Haeckel's multiplicity of roles, as both artist and naturalist, scientific specialist and popularizer of evolution, opponent of religion and monist philosopher, as well as the ambiguous classificaiton of his work (as scientific evidence, art, philosophical treatise, or racist propaganda) make it ethically difficult to evaluate Haeckel's scientific career.

Recapitulation theory

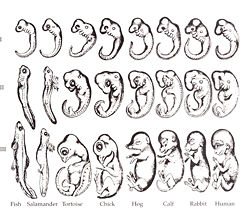

Haeckel advanced the "recapitulation theory" which proposed a link between ontogeny (development of form) and phylogeny (evolutionary descent), summed up in the phrase "ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny". The theory of recapitulation, also called the biogenetic law or ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny, is a theory in biology which attempts to explain apparent similarities between humans and other animals. First espoused in 1866 by German zoologist Ernst Haeckel, a contemporary of Charles Darwin, the theory has been discredited in its absolute form ("strong recapitulation"), although recognized as being perhaps partly fruitful. In biology, ontogeny is the embryonal development process of a certain species, and phylogeny a species' evolutionary history. Observers have noted various connections between phylogeny and ontogeny, explained them with evolutionary theory and taken them as supporting evidence for that theory.

Ontogeny is the growth (size change) and development (shape change) of an individual organism; phylogeny is the evolutionary history of a species. Haeckel's recapitulation theory claims that the development of the individual of every species fully repeats the evolutionary development of that species. Otherwise put, each successive stage in the development of an individual represents one of the adult forms that appeared in its evolutionary history.

Modern biology rejects the literal and universal form of Haeckel's theory. Although humans share ancestors with many other taxa (roughly, fish through reptiles to mammals), stages of human embryonic development are not functionally equivalent to the adults of these shared common ancestors. In other words, no cleanly defined and functional "fish", "reptile" and "mammal" stages of human embryonal development can be discerned. Moreover, development is nonlinear. For example, during kidney development, at one given time, the anterior region of the kidney is less developed (nephridium) than the posterior region (nephron).

The fact that contemporary biologists reject the literal or universal form of recapitulation theory has sometimes been used as an argument against evolution by some creationists. The argument is: "Haeckel's hypothesis was presented as supporting evidence for evolution, Haeckel's theory is wrong, therefore evolution has less support". This argument is not only an oversimplification but misleading because modern biology does recognize numerous connections between ontogeny and phylogeny, explains them using evolutionary theory without recourse to Haeckel's specific views, and considers them as supporting evidence for that theory.

Haeckel’s controversial embryo drawings

Haeckel supported recapitulation with embryo drawings that have since been shown to be oversimplified and in part inaccurate, and the theory is now considered an oversimplification of quite complicated relationships.

For example, Haeckel believed that the human embryo with gill slits (pharyngeal arches) in the neck not only signified a fishlike ancestor, but represented an adult "fishlike" developmental stage. Embryonic pharyngeal arches are not gills and do not carry out the same function. They are the invaginations between the gill pouches or pharyngeal pouches, and they open the pharynx to the outside. Gill pouches appear in all tetrapod animal embryos. In mammals, the first gill bar (in the first gill pouch) develops into the lower jaw (Meckel's cartilage), the malleus and the stapes. In a later stage, all gill slits close, with only the ear opening remaining open. for example the “gill slits” observed in the embryos’ “tailbud stage,” depicted in the top row, suggest the adult form of a common fish-like ancestor, while the curved tail, which develops soon after the gill slits, repeats a reptilian stage in evolution.

Some older editions of textbooks in the United States still erroneously cite recapitulation theory or the Haeckel drawings as evidence in support of evolution without appropriately explaining that they are misleading or outdated.

Haeckel monist philosophy and influence on Social Darwinism

h extended Darwinism beyond — ; science as the basis of all knowledge and human activity Haeckel extrapolated a new religion or philosophy called "monism" from evolutionary science. In Haeckel's view of monism, which postulates that all aspects of the world form an essential unity, all economics, politics, and ethics are reduced to "applied biology." [1] Haeckel's writings and lectures on monism were later used to provide scientific (or quasi-scientific) justifications for racism, nationalism, and social Darwinism.[1]

coined the term “monism” to contrast w/ “dualism” of man/nature, matter/spirit, materialism/idealism: way of countering the mechanical spirit of the age w/ a creative natural force, and of reviving the validity of Romantic volkism and naturphilosophie, which posited the common origins of life

Haeckel was also known for his "biogenic theory", in which he suggested that the development of races paralleled the development of individuals. He advocated the idea that "primitive" races were in their infancies and needed the "supervision" and "protection" of more "mature" societies.

Although Haeckel's specific form of recapitulation theory is now discredited among biologists, it did have a strong impact in social and educational theories of the late 19th century.

English philosopher Herbert Spencer was one of the most energetic promoters of evolutionary ideas to explain pretty well everything in sight; He compactly expressed the basis for a cultural recapitulation theory of education in the following claim:[2]

If there be an order in which the human race has mastered its various kinds of knowledge, there will arise in every child an aptitude to acquire these kinds of knowledge in the same order.... Education is a repetition of civilization in little.

The maturationist theory of G. Stanley Hall was based on the premise that growing children would recapitulate evolutionary stages of development as they grew up and that there was a one-to-one correspondence between childhood stages and evolutionary history, and that it was counterproductive to push a child ahead of its development stage. The whole notion fit nicely with other social Darwinist concepts, such as the idea that "primitive" societies needed guidance by more advanced societies, i.e. Europe and North America, which were considered by social Darwinists as the pinnacle of evolution. An early form of the law was devised by the 19th-century Estonian zoologist Karl Ernst von Baer, who observed that embryos resemble the embryos, but not the adults, of other species.

The publication of Ernst Haeckel's best-selling Welträtsel ('Riddle of the Universe') in 1899 brought social Darwinism and earlier ideas of "racial hygiene" to a wide audience, and its recapitulation theory became famous. This led to the formation of the Monist League in 1904 with many prominent citizens among its members, including the Nobel Prize winner Wilhelm Ostwald. By 1909, the Monist League had a membership of some six thousand people. [citation needed]

Haeckel influence as an artist

Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms of Nature) is Haeckel's book of lithographic and autotype prints. Originally published in sets of ten between 1899 and 1904 and as a complete volume in 1904, it consists of 100 prints of various organisms, many of which were first described by Haeckel himself. Over the course of his career, over 1000 engravings were produced based on Haeckel's sketches and watercolors; many of the best of these were chosen for Kunstformen der Natur, translated from sketch to print by lithographer Adolf Giltsch.[4]

According to Haeckel scholar Olaf Breidbach, the work was "not just a book of illustrations but also the summation of his view of the world." The overriding themes of the Kunstformen plates are symmetry and organization, central aspects of Haeckel's monism. The subjects were selected to embody organization, from the scale patterns of boxfishes to the spirals of ammonites to the perfect symmetries of jellies and microorganisms, while images composing each plate are arranged for maximum visual impact.[5]

Among the notable prints are numerous radiolarians, which Haeckel helped to popularize among amateur microscopists; at least one example is found in almost every set of 10.

Kunstformen der Natur played a role in the development of early 20th century art, architecture, and design, bridging the gap between science and art. In particular, many artists associated with the Art Nouveau movement were influenced by Haeckel's images, including René Binet, Karl Blossfeldt, Hans Christiansen, and Émile Gallé. One prominent example is the Amsterdam Commodities Exchange designed by Hendrik Petrus Berlage, which was in part inspired by Kunstformen illustrations.[6]

Biography

Early life and studies

Ernst Haeckel was born on February 16, 1834, in Potsdam (then a part of Prussia). In 1852, Haeckel completed studies at Cathedral High School (Domgymnasium) of Merseburg. Following his parents' wishes, he went on to study medicine at the Univerisity of Berlin, working with Albert von Kölliker, Franz Leydig, Rudolf Virchow, and anatomist-physiologist Johannes Müller (1801-1858). In 1857, Haeckel attained a doctorate in medicine (M.D.), and afterwards he received a license to practice medicine.

Overview of scientific career and later life

Haeckel studied under Carl Gegenbaur at the University of Jena for three years, earning a doctorate in zoology,[7] before becoming a professor of comparative anatomy at the University of Jena, where he remained 47 years, from 1862-1909. Between 1859 and 1866, Haeckel worked on many "invertebrate" groups, including radiolarians, poriferans (sea sponges) and annelids (segmented worms).[1] During a trip to the Mediterranean, Haeckel named nearly 150 new species of radiolarians.[1] "Invertebrates" provided the data for most of his experimental work on evolutionary development, leading to his "law of recapitulation." [1] Haeckel named thousands of new species from 1859 to 1887. [8]

Radiolarians (also radiolaria) are amoeboid protozoa that produce intricate mineral skeletons, typically with a central capsule dividing the cell into inner and outer portions, called endoplasm and ectoplasm. They are found as zooplankton throughout the ocean, and because of their rapid turn-over of species, their tests are important diagnostic fossils found from the Cambrian onwards. Some common radiolarian fossils include Actinomma, Heliosphaera and Hexadoridium.

German biologist Ernst Haeckel produced exquisite (and perhaps somewhat exaggerated) drawings of radiolaria, helping to popularize these protists among Victorian parlor microscopists alongside foraminifera and diatoms.

Haeckel was also a free-thinker who went beyond biological studies, dabbling in anthropology, psychology, and cosmology.[1] Haeckel's speculative ideas and possible fudging of data or diagrams, plus the lack of empirical support for many of his ideas, have tarnished his scientific credentials; however, Ernst Haeckel remained a very popular figure in Germany and was considered a hero by many of his countrymen.[1]

Haeckel was a flamboyant figure. He sometimes took great (and non-scientific) leaps from available evidence. For example, at the time that Darwin first published On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection (1859), no remains of human ancestors had yet been found. Haeckel postulated that evidence of human evolution would be found in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), and described these theoretical remains in great detail. He even named the as-of-yet unfound species, Pithecanthropus alalus, and charged his students to go find it. (Richard and Oskar Hertwig were two of Haeckel´s many important students.)

In 1909, Haeckel retired from teaching, and in 1910 he withdrew from the Evangelist church.[7] Haeckel's wife, Agnes, died in 1915, and Ernst Haeckel became substantially more frail, with a broken leg (thigh) and broken arm.[7] He sold the mansion Medusa ("Villa Medusa") in 1918 to the Carl Zeiss foundation.[7] Ernst Haeckel died on August 9, 1919.

The Ernst Haeckel house ("Villa Medusa") in Jena, Germany contains a historic library.

Works

Haeckel's literary output was extensive; at the time of the celebration of his sixtieth birthday at Jena in 1894, Haeckel had produced 42 works with nearly 13,000 pages, besides numerous scientific memoirs and illustrations.

Selected monographs

'Radiolaria (1862), Siphonophora (1869), Monera (1870) and Calcareous Sponges (1872), as well as several Challenger reports: Deep-Sea Medusae (1881), Siphonophora (1888), Deep-Sea Keratosa (1889), and another Radiolaria (1887), the last being illustrated with 140 plates and enumerating over four thousand (4000) new species.[9]

Selected published works

- 1866:General Morphology

- 1868: Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte (1868, in English, The Natural History of Creation reprinted 1883)

- 1874:Anthropogenie

- 1877:Freie Wissenschaft und freie Lehre (1877, in English, Freedom in Science and Teaching) in reply to a speech in which Virchow objected to the teaching of evolution in schools, on the grounds that evolution was an unproven hypothesis;[9]

- 1894:Die systematische Phylogenie (1894, "Systematic Phylogeny")

- 1895-1899:Die Welträthsel (1895-1899, also spelled Die Welträtsel ("world-riddle"), in English The Riddle of the Universe, 1901);[9]

- 1898:Über unsere gegenwärtige Kenntnis vom Ursprung des Menschen (1898, translated into English as The Last Link, 1908)

- 1904:Kunstformen der Natur (1904, Artforms of Nature), with plates representing detailed marine animal forms

- 1905:Der Kampf um den Entwickelungsgedanken (1905, English version, Last Words on Evolution, 1906)

- 1905:Wanderbilder (1905, "travel images"), with reproductions of his oil-paintings and water-color landscapes.[9]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 "Ernst Haeckel" (biography), UC Berkeley, 2004, webpage: BerkeleyEdu-Haeckel.

- ↑ Kieran Egan, The educated mind: How Cognitive Tools Shape Our Understanding., p.27 (University of Chicago Press, 1997, Chicago. ISBN 0-226-19036-6)

- ↑ Herbert Spencer (1861). Education, p.5.

- ↑ Breidbach, Visions of Nature, pp 253

- ↑ Breidbach, Visions of Nature, pp 229-231

- ↑ Breidbach, Visions of Nature, pp 231, 268-269

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHaeckelDE - ↑ "Rudolf Steiner and Ernst Haeckel" (colleagues), Daniel Hindes, 2005, DefendingSteiner.com webpage: Steiner-Haeckel.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHa1911

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gasman, Daniel. 1971. The Scientific Origins of National Socialism: Social Darwinism in Ernst Haeckel and the German Monist League. New York, NY: American Elsevier Inc.

- Milner, Richrad. 1993. The Encyclopedia of Evolution: Humanity's Search for Its Origins, New York, NY: Henry Holt.

- Richardson, Michael K. 1998. Haeckel's embryos continued, Science 281:1289.

- Richardson, M. K. & G. Keuck. March 8, 2001. A question of intent: when is a "schematic" illustration a fraud?, Nature 410:144.

- Ruse, M. 1979. The Darwinian Revolution. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

External links

- Marine Biological Laboratory Library - An exhibition of material on Haeckel, including background on many Kunsformen der Natur plates

- University of California, Berkeley - Ernst Haeckel biography

- Ernst Haeckel – Evolution's controversial artist. A slide-show essay about Ernst Haeckel.

- Kunstformen der Natur, Wikimedia Commons: over 100 detailed animal drawings.

- Kunstformen der Natur, scanned (from biolib.de Stuebers Online Library)

- PNG alpha-transparencies of Haeckel's "Kustformen der natur"

- Proteus - An animated documentary film on the life and work of Ernst Haeckel

- Ernst Haeckel Haus and Ernst Haeckel Museum in Jena

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.