Haeckel, Ernst

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (21 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebapproved}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| + | {{epname|Haeckel, Ernst}} | ||

| + | [[image:ErnstHaeckel.jpg|thumb|Ernst Haeckel, a professor of comparative anatomy at the University of Jena, was an early popularizer of Darwin's work in Germany.]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | '''Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel''' (February 16, 1834—August 9, 1919), |

| + | also written '''von Haeckel''', was an eminent German [[zoology|zoologist]] best known as an early promoter and popularizer of [[Charles Darwin|Charles Darwin's]] [[evolution|evolutionary theory]]. Haeckel developed the controversial [[recapitulation theory]], which claims that an individual organism's biological development, or [[ontogeny]], parallels in brief the entire evolutionary development of its species, or [[phylogeny]]. That is, according to Haeckel's formulation: ''Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny''. His concept of recapitulation has been discredited in its absolute form (now called ''strong recapitulation''). | ||

| − | ''' | + | As a professor of comparative anatomy at the University of Jena, Haeckel specialized in [[invertebrate]] [[anatomy]], working primarily on [[radiolarian]]s, a type of [[protozoa|protozoan]] [[plankton|zooplankton]] found throughout the ocean. Haeckel named thousands of new [[species]], mapped a genealogical tree relating all life forms, and coined many now ubiquitous terms in [[biology]], including ''[[phylum]]'', ''[[phylogeny]]'', and ''[[ecology]]''. He also discovered many species that he placed in the [[taxonomy#Scientific or biological classification|kingdom]] that he named ''[[Protista]]''. |

| − | |||

| − | + | Haeckel embraced [[evolution]] not only as a scientific theory, but as a worldview. He outlined a new [[religion]] or [[philosophy]] called [[monism]], which cast evolution as a cosmic force, a manifestation of the creative energy of nature. A proponent of [[social Darwinism]], Haeckel became increasingly involved in elaborating the social, political, and religious implications of Darwinism in the late nineteenth century; his writings and lectures on monism were later used to provide quasi-scientific justifications for the racist and [[imperialism|imperialist]] programs of [[National Socialism]] in 1930s [[Germany]]. | |

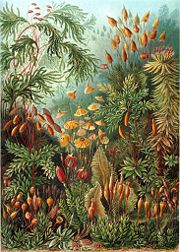

| − | + | Haeckel’s chief interests lay in evolution and life development processes in general, including the development of nonrandom form, which culminated in the beautifully illustrated ''Kunstformen der Natur'' ''(Art Forms of Nature)'', a collection of 100 detailed, multi-color illustrations of animals and sea creatures. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

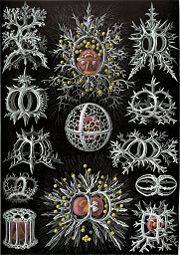

| + | [[Image:Haeckel_Stephoidea.jpg|thumb|180px|right|A plate from Ernst Haeckel's 1904 ''Kunstformen der Natur'' ''(Art Forms of Nature)'', showing radiolarians (a type of invertebrate group) belonging to the superfamily [[Stephoidea]]. Haeckel discovered thousands of new species of radiolarians.]] | ||

| + | Haeckel's multiplicity of roles, as both [[art|artist]] and [[naturalism|naturalist]], scientific specialist and popularizer of evolution, opponent of religion and monist philosopher, makes it difficult to evaluate Haeckel's scientific career and to classify his work. For example, while some of his drawings have been deemed forgeries for failing to adhere to the rigor of scientific evidence, they also reflect Haeckel's considerable ability to view nature with an artist's eye for symmetry and form. Thus, one the one hand, Haeckel's legacy of remarkable accomplishments has been tarnished by the apparently deliberately inaccurate drawings to support his scientific perspective, thus undermining one of the most important caches for a scientist, one's reputation for integrity. On the other hand, one of his most enduring positive legacies is his artistic drawings, which touch upon the inner nature of human beings—the desire for beauty; these drawings continue to be used to illustrate numerous topics in [[invertebrate|invertebrate zoology]]. | ||

| − | + | ==Biography== | |

| + | Ernst Haeckel was born on February 16, 1834, in Potsdam (then a part of [[Prussia]]). In 1852, Haeckel completed studies at Cathedral High School ''(Domgymnasium)'' of Merseburg. Following his parents' wishes, he went on to study [[medicine]] at the Univerisity of Berlin, working with [[Albert von Kölliker]], [[Franz Leydig]], [[Rudolf Virchow]], and anatomist-physiologist [[Johannes Müller]] (1801-1858). In 1857, Haeckel attained a doctorate in medicine (M.D.), and afterwards received a license to practice medicine. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Ernst Haeckel 1860.jpg|thumb|150px|right|Ernst Haeckel at age 26.]] | |

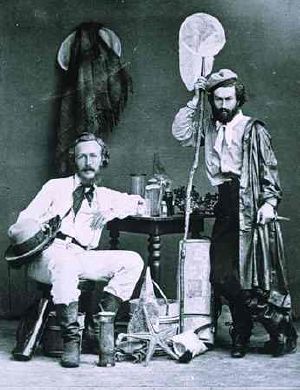

| + | [[image:Ernst Haeckel and von Miclucho-Maclay 1866.jpg|thumb|left|Haeckel (left) with [[Nicholai Miklukho-Maklai]], his assistant, in the [[Canary Islands|Canaries]], 1866.]] | ||

| − | [[ | + | Following a brief career in medicine, Haeckel returned to school to study under [[Carl Gegenbaur]] at the University of Jena. He earned a doctorate in [[zoology]], before becoming a professor of [[anatomy|comparative anatomy]] at the University of Jena, where he remained for 47 years, from 1862-1909. Between 1859 and 1866, Haeckel worked on many invertebrate groups, including radiolarians, [[porifera]]ns ([[sea sponge]]s), and [[annelid]]s (segmented worms) (Guralnick 1995). Invertebrates provided the data for most of his experimental work on evolutionary development, which led to his articulation of the theory of recapitulation (Guralnick 1995). Haeckel named thousands of new species from 1859 to 1887. |

| − | + | In 1909, Haeckel retired from teaching, and in 1910, he withdrew from the Evangelist church. | |

| − | + | After the death of Haeckel's second wife, Agnes, in 1915, Haeckel became considerably frailer. In 1918, he sold his mansion in Jena, Germany ("Villa Medusa") to the [[Carl Zeiss]] foundation; it now contains an historical library. Ernst Haeckel died on August 9, 1919. | |

==Recapitulation theory== | ==Recapitulation theory== | ||

| − | + | ===Synopsis of the theory=== | |

| − | + | Haeckel's recapitulation theory, also called the ''biogenetic law'', attempts to explain apparent similarities between [[human]]s and other animals. An early form of the law was devised by the nineteenth-century [[Estonia]]n [[zoology|zoologist]] [[Karl Ernst von Baer]], who observed that an embryo undergoing development moves toward increasing differentiation, which suggests, though does not prove, a “community of descent.” Haeckel's adaptation of recapitulation theory claims that the [[embryo|embryonic]] development of the individual of every [[species]] (ontogeny) fully repeats the historical development of the species (phylogeny). In other words, each successive stage in the development of an individual represents one of the adult forms that appeared in its evolutionary history. | |

| − | |||

| − | Modern biology rejects the literal and universal form of Haeckel's theory. Although [[Homo sapiens|humans]] share ancestors with many other taxa | + | Modern biology rejects the literal and universal form of Haeckel's theory. Although [[Homo sapiens|humans]] share ancestors with many other taxa, the stages of human embryonic development are not functionally equivalent to the adults of these shared common ancestors. In other words, no cleanly defined and functional "fish," "reptile," and "mammal" stages of human embryonal development can be discerned. Moreover, development is nonlinear. For example, during [[kidney]] development, at one given time, the anterior region of the kidney is less developed than the posterior region. |

| − | The fact that contemporary biologists reject the literal or universal form of recapitulation theory has sometimes been used as an argument against [[evolution]] by some [[creationism|creationists]]. The | + | The fact that contemporary biologists reject the literal or universal form of recapitulation theory has sometimes been used as an argument against [[evolution]] by some [[creationism|creationists]]. The main line of argumentation can be summarized as follows: if Haeckel's hypothesis was presented as supporting evidence for evolution, and it has now, in its strong form, been scientifically discredited, there is less support for evolutionary theory in general. This reasoning oversimplifies the issues at stake; it is also misleading because modern biology does recognize numerous connections between ontogeny and phylogeny, explains them using evolutionary theory without recourse to Haeckel's specific views, and considers them as supporting evidence for that theory. |

===Haeckel’s controversial embryo drawings=== | ===Haeckel’s controversial embryo drawings=== | ||

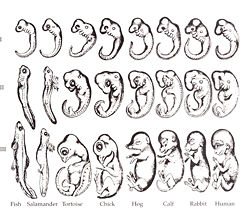

| − | [[Image:Haeckel_drawings.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:Haeckel_drawings.jpg|thumb|250px|A reproduction of Haeckel's controversial embryological drawings (which originally appeared as white figures on a black background). Scientists have established that Haeckel unduly emphasized the similarities across species.]] |

| − | Haeckel | + | Haeckel offered visual evidence for his recapitulation theory in the form of embryo drawings. The 24 figures in the drawing at right illustrate three stages in the development of eight [[vertebrate]] embryos. As the embryos move from an earlier to a later stage of development, we see a corresponding movement from a startling similarity across the specimens to a recognizable diversity of forms. According to Haeckel’s theory, the “gill slits” ([[pharyngeal arch]]es) observed in the embryos’ “tailbud stage,” depicted in the top row, suggest the adult form of a common [[fish]]-like ancestor, while the curved tail, which develops soon after the gill slits, repeats a [[reptile|reptilian]] stage in evolution. |

| − | For example, | + | Haeckel’s drawings have since been shown to be oversimplified and in part inaccurate (Richardson 1998; Richardson and Keuck 2001; Gould 2000). For example, embryonic pharyngeal arches are not [[gill]]s and do not carry out the same function as they do in adult fish. They are the invaginations between the [[gill pouch]]es or pharyngeal pouches, and they open the [[pharynx]] to the external environment. Even Haeckel's contemporaries criticized him for these misrepresentations, which, among other things, included doctoring drawings to make them more alike than they really are, and choosing only those embryos and life stages that came closest to fitting his theory. [[Stephen Jay Gould]] (2000) likewise claimed that Haeckel "exaggerated the similarieties by idealizations and omissions," and concluded they were characterized by "inaccuracies and outright falsification." |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

Some older editions of textbooks in the United States still erroneously cite recapitulation theory or the Haeckel drawings as evidence in support of evolution without appropriately explaining that they are misleading or outdated. | Some older editions of textbooks in the United States still erroneously cite recapitulation theory or the Haeckel drawings as evidence in support of evolution without appropriately explaining that they are misleading or outdated. | ||

| − | ==Haeckel | + | ==Haeckel impact on Social Darwinism== |

| − | + | Haeckel's recapitulationist theory had a strong impact on the English Social [[Darwinism|Darwinist]] [[Herbert Spencer]] and the [[maturationism|maturationist]] theory of [[G. Stanley Hall]]. But he contributed to Social Darwinism as a philosopher in his own right. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Haeckel's | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Haeckel extended Darwinism beyond its usefulness as a scientific theory; he extrapolated a new religion or philosophy called ''monism'' from evolutionary science. In Haeckel's view of monism, which postulates that all aspects of the world form an essential unity, all [[economics]], [[politics]], and [[ethics]] are reduced to "applied biology" (Guralnick 1995). | |

| − | + | Haeckel coined the term “monism” to contrast with the “dualisms” of man/nature, matter/spirit, [[materialism]]/[[idealism]]. [[Monism]] was a way of countering the mechanical spirit of the age with a creative natural force, and reviving the validity of earlier German movements such as [[Romantic volkism]] and [[naturphilosophie]], which, like evolutionary theory, posited the common origins of life. | |

| − | + | In his philosophical works, Haeckel suggested that the development of races paralleled the development of individuals. He advocated the idea that "primitive" races were in their infancies and needed the "supervision" and "protection" of more "mature" societies. | |

| − | + | The publication of Haeckel’s best-selling ''Welträtsel'' ''(The Riddle of the Universe)'' in 1899 brought Social Darwinism and earlier ideas of "racial hygiene" to a wide audience. This led to the formation of the Monist League in 1904, which had many prominent citizens among its members, including the [[Nobel Prize]] winner [[Wilhelm Ostwald]]. By 1909, the Monist League had a membership of some six thousand people. Haeckel and the Monists were an important source for diverse streams of thought that later came together under National Socialism. The most important and far-reaching influence of Haeckel's brand of Social Darwinism may be found among the leading figures of [[Eugenics]] and racial anthropology in Germany around the turn of the century. | |

| − | [[Image:Haeckel Actiniae.jpg|right|thumb|180px| | + | ==Haeckel influence as an artist== |

| + | [[Image:Haeckel Actiniae.jpg|right|thumb|180px|right|An illustration of sea anemones from ''Kunstformen der Natur''.]] | ||

| − | + | ''Kunstformen der Natur'' ''(Art Forms of Nature)'' is Haeckel's book of [[lithography|lithographic]] and [[autotype]] prints. Originally published in sets of ten between 1899 and 1904, and as a complete volume in 1904, it consists of 100 prints of various organisms, many of which were first described by Haeckel himself. Over the course of his career, over 1000 [[engraving]]s were produced based on Haeckel's sketches and watercolors; many of the best of these were chosen for ''Kunstformen der Natur'', translated from sketch to print by lithographer Adolf Giltsch (Breidbach 2006). | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | + | According to Haeckel scholar Olaf Breidbach (2006), the work was "not just a book of illustrations but also the summation of his view of the world." The overriding themes of the ''Kunstformen'' plates are symmetry and organization, central aspects of Haeckel's [[monism]]. The subjects were selected to embody organization, from the scale patterns of [[boxfish]]es to the spirals of [[ammonite]]s to the perfect symmetries of jellies and microorganisms, while images composing each plate are arranged for maximum visual impact (Breidbach 2006). | |

| − | + | [[Image:Haeckel Muscinae.jpg|thumb|180px|left|A plate depicting [[muscinae]].]] | |

| − | + | Among the notable prints are numerous radiolarians, which Haeckel helped to popularize among amateur microscopists; at least one example is found in almost every set of 10. | |

| − | |||

| − | Haeckel | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ''' | + | ''Kunstformen der Natur'' played a role in the development of early twentieth century art, architecture, and design, bridging the gap between science and art. In particular, many artists associated with the [[Art Nouveau]] movement were influenced by Haeckel's images, including [[René Binet]], [[Karl Blossfeldt]], [[Hans Christiansen]], and [[Émile Gallé]]. One prominent example is the Amsterdam Commodities Exchange designed by Hendrik Petrus Berlage, which was in part inspired by ''Kunstformen'' illustrations (Breidbach 2006). |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Works== | ==Works== | ||

| − | + | Haeckel's literary output was extensive; at the time of the celebration of his sixtieth birthday in 1894, Haeckel had produced 42 works totaling nearly 13,000 pages, besides numerous scientific memoirs and illustrations. | |

| − | Haeckel's literary output was extensive; at the time of the celebration of his sixtieth birthday | ||

===Selected monographs=== | ===Selected monographs=== | ||

| − | 'Radiolaria'' ( | + | Haeckel's published monographs include ''Radiolaria'' (1862), ''Siphonophora'' (1869), ''Monera'' (1870), and ''Calcareous Sponges'' (1872), as well as several ''Challenger'' reports, including ''Deep-Sea Medusae'' (1881), ''Siphonophora'' (1888), and ''Deep-Sea Keratosa'' (1889). Another edition of ''Radiolaria'' was published in 1887, illustrated with 140 plates and enumerating over 4,000 new species (MAC 1911). |

===Selected published works=== | ===Selected published works=== | ||

| − | *1866:''General Morphology'' | + | *1866: ''Generalle Morphologie der Organismen'' ''(General Morphology)'' |

| − | *1868: ''Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte'' ( | + | *1868: ''Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte'' (in English, ''The Natural History of Creation,'' reprinted 1883) |

| − | *1874:''Anthropogenie'' | + | *1874: ''Anthropogenie'' (published in English as ''The Evolution of Man: a Popular Exposition of the Principal Points of Human Ontogeny and Phylogeny,'' 1903) |

| − | *1877:''Freie Wissenschaft und freie Lehre'' ( | + | *1877: ''Freie Wissenschaft und freie Lehre'' (published in English as ''Freedom in Science and Teaching,'' 1879) |

| − | *1894:''Die systematische Phylogenie'' ( | + | *1892: ''Der Monismus als Band zwischen Religion und Wissenschaft'' (published in English as ''Monism as Connecting Religion and Science. The Confession of Faith of a Man of Science'', 1894) |

| − | *1895-1899:''Die Welträthsel'' | + | *1894: ''Die systematische Phylogenie'' ''(Systematic Phylogeny)'' |

| − | *1898:''Über unsere gegenwärtige Kenntnis vom Ursprung des Menschen'' ( | + | *1895-1899: ''Die Welträthsel'', also spelled ''Die Welträtsel'' (published in English as ''The Riddle of the Universe at the Close of the Nineteenth Century'', 1900) |

| − | *1904:'' | + | *1898:''Über unsere gegenwärtige Kenntnis vom Ursprung des Menschen'' (translated into English as ''The Last Link'', 1908) |

| − | *1905:''Der Kampf um den Entwickelungsgedanken'' ( | + | *1904: ''Kunstformen der Natur'' ''(Art Forms of Nature)'' |

| − | *1905:''Wanderbilder'' ( | + | *1905: ''Der Kampf um den Entwickelungsgedanken'' (published in English as ''Last Words on Evolution'', 1906) |

| + | *1905: ''Wanderbilder'' ("travel images") | ||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | |||

| − | + | * Breidbach, O. 2006. ''Visions of Nature: The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel''. Munich: Prestel. ISBN 3791336649. | |

| − | *Gasman, | + | * Dombrowski, P. 2003. Ernst Haeckel's controversial visual rhetoric, ''Technical Communication Quarterly'' 12: 303-319. |

| − | *Milner, | + | * Gasman, D. 1971. ''The Scientific Origins of National Socialism: Social Darwinism in Ernst Haeckel and the German Monist League''. New York, NY: American Elsevier Inc. ISBN 0444196641. |

| − | *Richardson, | + | * Gould, S. J. 2000. Abscheulich! - Atrocious!: The precursor to the theory of natural selection. ''Natural History'' March, 2000. |

| − | *Richardson, M. K. | + | * Guralnick, R. P. 1995. [http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/history/haeckel.html Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919)]. ''University fo California Museum of Paleontology''. Retreived June 4, 2007. |

| − | *Ruse, M. 1979. ''The Darwinian Revolution''. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. | + | * Milner, R. 1993. ''The Encyclopedia of Evolution: Humanity's Search for Its Origins''. New York, NY: Henry Holt. ISBN 0805027173. |

| + | * Missouri Association for Creation (MAC). 1911. [http://www.gennet.org/facts/haeckel.html Biography of Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, 1834-1919]. ''Missouri Association for Creation'', based on 1911 Britannica. Retrieved June 4, 2007. | ||

| + | * Richardson, M. K. 1998. Haeckel's embryos continued. ''Science'' 281: 1289. | ||

| + | * Richardson, M. K., and G. Keuck. 2001. A question of intent: When is a "schematic" illustration a fraud? ''Nature'' 410: 144. | ||

| + | * Ruse, M. 1979. ''The Darwinian Revolution''. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. | ||

| + | * Wells, J. 2000. ''Icons of Evolution''. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0895262762. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved March 20, 2024. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | * [http://draves.org/pix/kdn/ PNG alpha-transparencies of Haeckel's "Kustformen der natur"]. | |

| − | + | *[http://www.nightfirefilms.org/proteus_home.html Proteus] - An animated documentary film on the life and work of Ernst Haeckel. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [http://draves.org/pix/kdn/ PNG alpha-transparencies of Haeckel's "Kustformen der natur"] | ||

| − | *[http://www.nightfirefilms.org/proteus_home.html Proteus] - An animated documentary film on the life and work of Ernst Haeckel | ||

| − | |||

| − | {{credit|101184758}} | + | {{credit|Ernst_Haeckel|101184758|Recapitulation_theory|133979243|Social_Darwinism|135503464|Radiolarian|129681356|Kunstformen_der_Natur|134064634|World_riddle|117715400}} |

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Biologists]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Evolution]] | ||

Latest revision as of 21:22, 20 March 2024

Ernst Heinrich Philipp August Haeckel (February 16, 1834—August 9, 1919), also written von Haeckel, was an eminent German zoologist best known as an early promoter and popularizer of Charles Darwin's evolutionary theory. Haeckel developed the controversial recapitulation theory, which claims that an individual organism's biological development, or ontogeny, parallels in brief the entire evolutionary development of its species, or phylogeny. That is, according to Haeckel's formulation: Ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. His concept of recapitulation has been discredited in its absolute form (now called strong recapitulation).

As a professor of comparative anatomy at the University of Jena, Haeckel specialized in invertebrate anatomy, working primarily on radiolarians, a type of protozoan zooplankton found throughout the ocean. Haeckel named thousands of new species, mapped a genealogical tree relating all life forms, and coined many now ubiquitous terms in biology, including phylum, phylogeny, and ecology. He also discovered many species that he placed in the kingdom that he named Protista.

Haeckel embraced evolution not only as a scientific theory, but as a worldview. He outlined a new religion or philosophy called monism, which cast evolution as a cosmic force, a manifestation of the creative energy of nature. A proponent of social Darwinism, Haeckel became increasingly involved in elaborating the social, political, and religious implications of Darwinism in the late nineteenth century; his writings and lectures on monism were later used to provide quasi-scientific justifications for the racist and imperialist programs of National Socialism in 1930s Germany.

Haeckel’s chief interests lay in evolution and life development processes in general, including the development of nonrandom form, which culminated in the beautifully illustrated Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms of Nature), a collection of 100 detailed, multi-color illustrations of animals and sea creatures.

Haeckel's multiplicity of roles, as both artist and naturalist, scientific specialist and popularizer of evolution, opponent of religion and monist philosopher, makes it difficult to evaluate Haeckel's scientific career and to classify his work. For example, while some of his drawings have been deemed forgeries for failing to adhere to the rigor of scientific evidence, they also reflect Haeckel's considerable ability to view nature with an artist's eye for symmetry and form. Thus, one the one hand, Haeckel's legacy of remarkable accomplishments has been tarnished by the apparently deliberately inaccurate drawings to support his scientific perspective, thus undermining one of the most important caches for a scientist, one's reputation for integrity. On the other hand, one of his most enduring positive legacies is his artistic drawings, which touch upon the inner nature of human beings—the desire for beauty; these drawings continue to be used to illustrate numerous topics in invertebrate zoology.

Biography

Ernst Haeckel was born on February 16, 1834, in Potsdam (then a part of Prussia). In 1852, Haeckel completed studies at Cathedral High School (Domgymnasium) of Merseburg. Following his parents' wishes, he went on to study medicine at the Univerisity of Berlin, working with Albert von Kölliker, Franz Leydig, Rudolf Virchow, and anatomist-physiologist Johannes Müller (1801-1858). In 1857, Haeckel attained a doctorate in medicine (M.D.), and afterwards received a license to practice medicine.

Following a brief career in medicine, Haeckel returned to school to study under Carl Gegenbaur at the University of Jena. He earned a doctorate in zoology, before becoming a professor of comparative anatomy at the University of Jena, where he remained for 47 years, from 1862-1909. Between 1859 and 1866, Haeckel worked on many invertebrate groups, including radiolarians, poriferans (sea sponges), and annelids (segmented worms) (Guralnick 1995). Invertebrates provided the data for most of his experimental work on evolutionary development, which led to his articulation of the theory of recapitulation (Guralnick 1995). Haeckel named thousands of new species from 1859 to 1887.

In 1909, Haeckel retired from teaching, and in 1910, he withdrew from the Evangelist church.

After the death of Haeckel's second wife, Agnes, in 1915, Haeckel became considerably frailer. In 1918, he sold his mansion in Jena, Germany ("Villa Medusa") to the Carl Zeiss foundation; it now contains an historical library. Ernst Haeckel died on August 9, 1919.

Recapitulation theory

Synopsis of the theory

Haeckel's recapitulation theory, also called the biogenetic law, attempts to explain apparent similarities between humans and other animals. An early form of the law was devised by the nineteenth-century Estonian zoologist Karl Ernst von Baer, who observed that an embryo undergoing development moves toward increasing differentiation, which suggests, though does not prove, a “community of descent.” Haeckel's adaptation of recapitulation theory claims that the embryonic development of the individual of every species (ontogeny) fully repeats the historical development of the species (phylogeny). In other words, each successive stage in the development of an individual represents one of the adult forms that appeared in its evolutionary history.

Modern biology rejects the literal and universal form of Haeckel's theory. Although humans share ancestors with many other taxa, the stages of human embryonic development are not functionally equivalent to the adults of these shared common ancestors. In other words, no cleanly defined and functional "fish," "reptile," and "mammal" stages of human embryonal development can be discerned. Moreover, development is nonlinear. For example, during kidney development, at one given time, the anterior region of the kidney is less developed than the posterior region.

The fact that contemporary biologists reject the literal or universal form of recapitulation theory has sometimes been used as an argument against evolution by some creationists. The main line of argumentation can be summarized as follows: if Haeckel's hypothesis was presented as supporting evidence for evolution, and it has now, in its strong form, been scientifically discredited, there is less support for evolutionary theory in general. This reasoning oversimplifies the issues at stake; it is also misleading because modern biology does recognize numerous connections between ontogeny and phylogeny, explains them using evolutionary theory without recourse to Haeckel's specific views, and considers them as supporting evidence for that theory.

Haeckel’s controversial embryo drawings

Haeckel offered visual evidence for his recapitulation theory in the form of embryo drawings. The 24 figures in the drawing at right illustrate three stages in the development of eight vertebrate embryos. As the embryos move from an earlier to a later stage of development, we see a corresponding movement from a startling similarity across the specimens to a recognizable diversity of forms. According to Haeckel’s theory, the “gill slits” (pharyngeal arches) observed in the embryos’ “tailbud stage,” depicted in the top row, suggest the adult form of a common fish-like ancestor, while the curved tail, which develops soon after the gill slits, repeats a reptilian stage in evolution.

Haeckel’s drawings have since been shown to be oversimplified and in part inaccurate (Richardson 1998; Richardson and Keuck 2001; Gould 2000). For example, embryonic pharyngeal arches are not gills and do not carry out the same function as they do in adult fish. They are the invaginations between the gill pouches or pharyngeal pouches, and they open the pharynx to the external environment. Even Haeckel's contemporaries criticized him for these misrepresentations, which, among other things, included doctoring drawings to make them more alike than they really are, and choosing only those embryos and life stages that came closest to fitting his theory. Stephen Jay Gould (2000) likewise claimed that Haeckel "exaggerated the similarieties by idealizations and omissions," and concluded they were characterized by "inaccuracies and outright falsification."

Some older editions of textbooks in the United States still erroneously cite recapitulation theory or the Haeckel drawings as evidence in support of evolution without appropriately explaining that they are misleading or outdated.

Haeckel impact on Social Darwinism

Haeckel's recapitulationist theory had a strong impact on the English Social Darwinist Herbert Spencer and the maturationist theory of G. Stanley Hall. But he contributed to Social Darwinism as a philosopher in his own right.

Haeckel extended Darwinism beyond its usefulness as a scientific theory; he extrapolated a new religion or philosophy called monism from evolutionary science. In Haeckel's view of monism, which postulates that all aspects of the world form an essential unity, all economics, politics, and ethics are reduced to "applied biology" (Guralnick 1995).

Haeckel coined the term “monism” to contrast with the “dualisms” of man/nature, matter/spirit, materialism/idealism. Monism was a way of countering the mechanical spirit of the age with a creative natural force, and reviving the validity of earlier German movements such as Romantic volkism and naturphilosophie, which, like evolutionary theory, posited the common origins of life.

In his philosophical works, Haeckel suggested that the development of races paralleled the development of individuals. He advocated the idea that "primitive" races were in their infancies and needed the "supervision" and "protection" of more "mature" societies.

The publication of Haeckel’s best-selling Welträtsel (The Riddle of the Universe) in 1899 brought Social Darwinism and earlier ideas of "racial hygiene" to a wide audience. This led to the formation of the Monist League in 1904, which had many prominent citizens among its members, including the Nobel Prize winner Wilhelm Ostwald. By 1909, the Monist League had a membership of some six thousand people. Haeckel and the Monists were an important source for diverse streams of thought that later came together under National Socialism. The most important and far-reaching influence of Haeckel's brand of Social Darwinism may be found among the leading figures of Eugenics and racial anthropology in Germany around the turn of the century.

Haeckel influence as an artist

Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms of Nature) is Haeckel's book of lithographic and autotype prints. Originally published in sets of ten between 1899 and 1904, and as a complete volume in 1904, it consists of 100 prints of various organisms, many of which were first described by Haeckel himself. Over the course of his career, over 1000 engravings were produced based on Haeckel's sketches and watercolors; many of the best of these were chosen for Kunstformen der Natur, translated from sketch to print by lithographer Adolf Giltsch (Breidbach 2006).

According to Haeckel scholar Olaf Breidbach (2006), the work was "not just a book of illustrations but also the summation of his view of the world." The overriding themes of the Kunstformen plates are symmetry and organization, central aspects of Haeckel's monism. The subjects were selected to embody organization, from the scale patterns of boxfishes to the spirals of ammonites to the perfect symmetries of jellies and microorganisms, while images composing each plate are arranged for maximum visual impact (Breidbach 2006).

Among the notable prints are numerous radiolarians, which Haeckel helped to popularize among amateur microscopists; at least one example is found in almost every set of 10.

Kunstformen der Natur played a role in the development of early twentieth century art, architecture, and design, bridging the gap between science and art. In particular, many artists associated with the Art Nouveau movement were influenced by Haeckel's images, including René Binet, Karl Blossfeldt, Hans Christiansen, and Émile Gallé. One prominent example is the Amsterdam Commodities Exchange designed by Hendrik Petrus Berlage, which was in part inspired by Kunstformen illustrations (Breidbach 2006).

Works

Haeckel's literary output was extensive; at the time of the celebration of his sixtieth birthday in 1894, Haeckel had produced 42 works totaling nearly 13,000 pages, besides numerous scientific memoirs and illustrations.

Selected monographs

Haeckel's published monographs include Radiolaria (1862), Siphonophora (1869), Monera (1870), and Calcareous Sponges (1872), as well as several Challenger reports, including Deep-Sea Medusae (1881), Siphonophora (1888), and Deep-Sea Keratosa (1889). Another edition of Radiolaria was published in 1887, illustrated with 140 plates and enumerating over 4,000 new species (MAC 1911).

Selected published works

- 1866: Generalle Morphologie der Organismen (General Morphology)

- 1868: Natürliche Schöpfungsgeschichte (in English, The Natural History of Creation, reprinted 1883)

- 1874: Anthropogenie (published in English as The Evolution of Man: a Popular Exposition of the Principal Points of Human Ontogeny and Phylogeny, 1903)

- 1877: Freie Wissenschaft und freie Lehre (published in English as Freedom in Science and Teaching, 1879)

- 1892: Der Monismus als Band zwischen Religion und Wissenschaft (published in English as Monism as Connecting Religion and Science. The Confession of Faith of a Man of Science, 1894)

- 1894: Die systematische Phylogenie (Systematic Phylogeny)

- 1895-1899: Die Welträthsel, also spelled Die Welträtsel (published in English as The Riddle of the Universe at the Close of the Nineteenth Century, 1900)

- 1898:Über unsere gegenwärtige Kenntnis vom Ursprung des Menschen (translated into English as The Last Link, 1908)

- 1904: Kunstformen der Natur (Art Forms of Nature)

- 1905: Der Kampf um den Entwickelungsgedanken (published in English as Last Words on Evolution, 1906)

- 1905: Wanderbilder ("travel images")

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Breidbach, O. 2006. Visions of Nature: The Art and Science of Ernst Haeckel. Munich: Prestel. ISBN 3791336649.

- Dombrowski, P. 2003. Ernst Haeckel's controversial visual rhetoric, Technical Communication Quarterly 12: 303-319.

- Gasman, D. 1971. The Scientific Origins of National Socialism: Social Darwinism in Ernst Haeckel and the German Monist League. New York, NY: American Elsevier Inc. ISBN 0444196641.

- Gould, S. J. 2000. Abscheulich! - Atrocious!: The precursor to the theory of natural selection. Natural History March, 2000.

- Guralnick, R. P. 1995. Ernst Haeckel (1834-1919). University fo California Museum of Paleontology. Retreived June 4, 2007.

- Milner, R. 1993. The Encyclopedia of Evolution: Humanity's Search for Its Origins. New York, NY: Henry Holt. ISBN 0805027173.

- Missouri Association for Creation (MAC). 1911. Biography of Ernst Heinrich Haeckel, 1834-1919. Missouri Association for Creation, based on 1911 Britannica. Retrieved June 4, 2007.

- Richardson, M. K. 1998. Haeckel's embryos continued. Science 281: 1289.

- Richardson, M. K., and G. Keuck. 2001. A question of intent: When is a "schematic" illustration a fraud? Nature 410: 144.

- Ruse, M. 1979. The Darwinian Revolution. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Wells, J. 2000. Icons of Evolution. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0895262762.

External links

All links retrieved March 20, 2024.

- PNG alpha-transparencies of Haeckel's "Kustformen der natur".

- Proteus - An animated documentary film on the life and work of Ernst Haeckel.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Ernst_Haeckel history

- Recapitulation_theory history

- Social_Darwinism history

- Radiolarian history

- Kunstformen_der_Natur history

- World_riddle history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.