Gaon, Vilna

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (52 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{epname|Vilna | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

| + | {{epname|Gaon, Vilna}} | ||

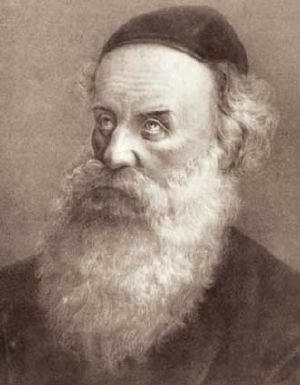

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Gaon2.jpg|right|thumb|230px|Elijah ben Solomon, the Vilna Gaon]] |

| + | '''Elijah ben Solomon,''' better known as the '''Vilna Gaon''' (April 23, 1720 – October 9, 1797), was the foremost intellectual leader of non-[[Hasidic]] [[Jewry]] in eighteenth century Europe. Among Jews, he is often referred to the '''The Gra'''—from the [[Hebrew language|Hebrew]] [[acronym]] "'''G'''aon '''R'''abbi '''E'''liyahu." | ||

| − | + | Born in [[Vilnius]], [[Grand Duchy of Lithuania|Lithuania]], the Vilna Gaon displayed extraordinary talent while still a child. By the time he was 20 years old, [[rabbi]]s were reportedly submitting their most difficult ''[[Halakha|halakhic]]'' (Jewish legal) problems to him for rulings. He was also a voluminous author, writing commentaries on virtually all of the classical sources of Jewish legal tradition. | |

| − | + | Broad-minded but disciplined in his approach to Talmudic study and ascetic in his lifestyle, the Vilna Gaon pioneered a frank, critical examination of texts. He thus rejected the prevalent ''pilpul'' school, which went to great lengths to reconcile apparently contradictory precedents found in Jewish legal texts such as the [[Mishnah]], the [[Talmud]], the [[Shulchan Aruch]], and later rabbinical rulings. | |

| − | When [[Hasidic Judaism]] became influential in | + | When the fervent enthusiasm of [[Hasidic Judaism]] became influential in [[Vilnius]], the usually retiring Vilna Gaon joined with the rabbis who sought to repress Hasidic influence. As a result, one of the first mass [[excommunication]]s against the Hasidim was launched in Vilnius in 1777. The Vilna Gaon continued persecuting the Hasidim, at intervals, throughout the rest of his life. |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | In addition to voluminous rabbinical and mystical works, the Vilna Gaon also wrote on [[mathematics]] and encouraged his pupil, Rabbi [[Baruch of Shklov]], to translate the works of [[Euclid]] into Hebrew. After his death, his primary disciple, Rabbi [[Chaim Volozhin]], founded a [[yeshiva]] at [[Volozhin]] in 1803, which became a major influence on later [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox Jewry]]. Among non-Hasidic Jews, the Vilna Goan became one of the most influential rabbinic authorities since the [[Middle Ages]]. Many [[Ashkenazi]] Jewish authorities and ''yeshivas'' uphold [[Judaism|Jewish customs and rites]], known as the ''minhag ha-Gra,'' named for him. His followers were also among the first modern Jews to immigrate to the future land of Israel, where his influence continues to be strongly felt. | |

==Youth and education== | ==Youth and education== | ||

| − | + | The Vilna Gaon's given Hebrew name was Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman. The term "Gaon" was an honorific title previously given to heads of major Jewish academies, sometimes translated as "genius." "Vilna" is simply the name of his city of [[Vilnius]], in today's [[Lithuania]]. Ironically, the Vilna Gaon never headed a school, although his personal pupils became very influential and gave him the title of Gaon to honor his status as their teacher. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Legend holds that young Elijah be Solomon was a [[child prodigy]] who had committed the [[Hebrew Bible]] to memory by the age of three. He reportedly possessed a [[photographic memory]]. At seven he was taught [[Talmud]] by [[Moses Margalit]], the influential rabbi of [[Kėdainiai]]. By eight, he was studying [[astronomy]] during his free time. From the age of ten, he continued his studies without the aid of a teacher, and at 11 he had reportedly committed the entire Talmud to memory. | |

| − | + | By his teens, Elijah's intellectual gifts were already famous. He traveled in various parts of Europe, including [[Poland]] and [[Germany]], as was the custom of the pious Jews of the time who could afford to do so. By the time he was 20, rabbis began submitting their most difficult ''[[Halakha|halakhic]]'' problems to him. Scholars, both Jewish and non-Jewish, sought his insights into [[mathematics]] and [[astronomy]]. He returned to his native town of Vilnius/Vilna in 1748, having by then acquired considerable renown. | |

| − | + | ==Methodology and character== | |

| + | [[Image:Vilna Gaon portrait.gif|right|framed|Portrait of a young ''Vilna Gaon'']] | ||

| + | The Vilna Gaon applied formal philological methods to study the [[Talmud]] and rabbinic literature. A proponent of intellect over emotion, he nonetheless took a broader approach than his predecessors of the ''[[pilpul]]'' school of Talmudism, which went to great trouble to attempt to reconcile apparent contradictions presented in Jewish legal texts. Instead, he engaged in a rigorous but frank critical examination and was more than willing to confront contradictions; nor was he unwilling at times to overthrow the decisions made by his rabbinic predecessors. | ||

| − | + | Not content to concentrate on the [[Talmud]] and subsequent commentaries alone, the Vilna Gaon devoted much time to the study of the [[Hebrew Bible]] and [[grammar]]. He was also knowledgeable in the secular sciences. Despite his later opposition to the [[mysticism]] of the [[[[Hasidic Judaism|Hasidim]], the "Gra" was himself attracted to the study of [[Kabbalah]]. He was thus not opposed to mysticism ''per se,'' but emphasized the need for Kabbalah to be practiced only within the bounds of [[halakhah|Jewish law]] and on the foundation of disciplined Talmudic study. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The Vilna Gaon rarely took part in public affairs and, so far as is known, did not preside over any school in [[Vilna]]. He was satisfied with lecturing in private to a few chosen pupils. He was especially anxious to introduce them to the study of the [[Hebrew Bible]], the [[midrash]]ic literature, and the [[Minor Treatises]] of the Talmud, which were very little known by the scholars of his time. Unlike the other Jewish scholars, the Vilna Gaon also laid special stress on the study of the [[Jerusalem Talmud]]—in addition to the Babylonian version—which had been almost entirely neglected for centuries. | |

| − | + | The Gra was reportedly very modest and objective in his personal attitude, eschewing both passion and public controversy. Despite his high authority, he declined to accept the office of Vilnius' chief [[rabbi]], although it was often offered to him on the most flattering terms. | |

| − | + | His life was an [[ascetic]] one, as he interpreted literally the words of certain Jewish sages that the [[Torah]] can be truly acquired only by abandoning all pleasures and cheerfully accepting suffering. Although this put him squarely at odds with the joyous, life-affirming tradition of the [[Hasidim]], he was revered by many of his countrymen as a saint, being called by some of his contemporaries "the ''Hasid,''" meaning "pious one." | |

| − | == | + | ==Antagonism to Hasidism== |

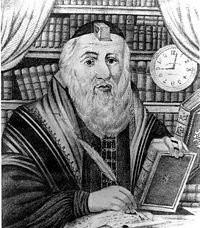

| − | + | [[Image:Schneur Zalman of Liadi.jpg|thumb|The Hasidic leader Rabbi [[Schneur Zalman of Liadi]]]] | |

| + | [[Image:Gaon-V.jpg|thumb|200px|left|The Vilna Gaon was the leading opponent of the Hasidim of his time]] | ||

| + | The exception to the rule of the Vilna Gaon's humility and reservation came with regard to the spread of [[Hasidic Judaism]]. This movement had grown up in opposition to the dry intellectualism of the prevailing Jewish religious leadership, emphasizing instead a fervent personal relationship with God that made mystical experience more important than formal [[Talmud]]ic study. When Hasidim became influential in his native Vilnius, the Vilna Gaon joined the ''[[Mitnagdim]]''—the [[rabbi]]s and heads of the neighboring Jewish communities opposed to Hasidism—and took direct steps to check the Hasidic influence. | ||

| − | + | Under his influence, in 1777 one of the first mass [[excommunication]]s against the Hasidim was launched in Vilnius. A letter was also addressed to all of the large Jewish communities, exhorting them to deal with the Hasidim following Vilinius' example, and to put the Hasidim under surveillance until they had recanted. The letter was acted upon by several communities, resulting in the Hasidim closing the Hasidic houses of worship and a temporary retreat of their evangelical efforts. According to [[Chabad]] tradition, the Hasidic leader the [[Maggid of Mezeritch]] sent Rabbi [[Shneur Zalman of Liadi]] and Rabbi [[Menachem Mendel Horodoker]] to the Vilna Gaon to dialog with him, but the Gaon refused to meet with them. | |

| − | + | The persecution thus temporarily drove the Hasidic movement underground, but in 1781, when the Hasidim renewed their proselytizing work under the leadership of Shneur Zalman, the Vilna Gaon excommunicated the Hasidim again, this time publicly declaring them to be [[heretic]]s with whom no pious [[Jew]] might intermarry or associate. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | After this, the Gaon went into retirement again, concentrating on his writing and teaching his select pupils. Eventually, a rumor spread he had changed his mind and had even repented of having persecuted the Hasidim. In 1796, the Gaon reacted to this by sending two of his pupils with letters throughout the Jewish communities of Greater [[Poland]], declaring that he had by no means changed his attitude in the matter. Neither the excommunications nor the Gaon's letters, however, could stop the tide of Hasidism, which remained a major trend throughout much of Eastern Europe. | |

==Works== | ==Works== | ||

| − | The Vilna Gaon was a voluminous author; there is hardly an ancient Hebrew book of any importance to which he did not write a commentary, or at least provide marginal glosses and notes, which were mostly dictated to his pupils. However, nothing of his was published in his lifetime | + | The Vilna Gaon was a voluminous author; there is hardly an ancient Hebrew book of any importance to which he did not write a commentary, or at least provide marginal glosses and notes, which were mostly dictated to his pupils. However, nothing of his was published in his lifetime. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | His glosses on the [[Talmud|Babylonian Talmud]] and ''[[Shulchan Aruch]]'' are known as ''Biurei ha-Gra'' ("Elaboration by the Gra"). His running commentary on the [[Mishnah]] is titled ''Shenoth Eliyahu'' ("The Years of Elijah"). Various [[Kabbalah|kabbalistic]] works also have commentaries in his name. His insights on the [[Torah|Pentateuch]] are titled ''Adereth Eliyahu'' ("The Splendor of Elijah"). Later in his life, he also wrote commentaries on the [[Book of Proverbs|Proverbs]] and other books of the [[Hebrew Bible]]. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The Vilna Gaon also wrote on mathematics, being well versed in the works of [[Euclid]] and encouraging his pupil Rabbi Baruch of Shklov to translate the great mathematician's works into Hebrew. | |

| − | + | ==Legacy== | |

| − | + | After his death in 1797, aged 77, the Vilna Gaon was buried in the Šnipiškės cemetery in Vilnius. The cemetery was closed by the tsarist Russian authorities in 1831 and partly built over. In the 1950s, Soviet authorities planned to build a stadium and concert hall on the site. They allowed the remains of the "Gra" to be removed and re-interred at the new cemetery. | |

| − | + | The Vilna Gaon was one of the most influential rabbinic authorities since the [[Middle Ages]]. Many ''[[yeshiva]]s'' today uphold the set of customs that can be traced back to him, known as the ''minhag ha-Gra''. His main student, Rabbi [[Chaim Volozhin]], founded the first yeshiva in his home town of [[Volozhin]], [[Belarus]]. The results of this move revolutionized [[Torah study]] and are still felt throughout much of [[Orthodox Judaism]] today. | |

| − | + | In accordance with the Vilna Gaon's wishes, three groups of his disciples and their families, numbering over 500, immigrated to the [[Eretz Yisrael|Land of Israel]] between 1808 and 1812. This movement is considered by some to be the beginning of the modern Jewish settlement of Israel. As a result of this movement, the teachings of the Vilna Gaon have had a considerable influence on Jewish thought and religious practice among the Ashkenazi community in Israel. | |

| − | + | There is a statue of the Vilna Gaon and a street named after him in the central city of Vilnius, the place of both his birth and his death. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Orthodox Judaism]] |

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Hasidic Judaism]] |

*[[Mitnagdim]] | *[[Mitnagdim]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | * Ackerman, C.D. (trans.). ''Even Sheleimah: The Vilna Gaon Looks at Life''. Targum Press, 1994. ISBN 0944070965. | ||

| + | * Etkes, Immanuel, et al. ''The Gaon of Vilna: The Man and His Image''. University of California Press, 2002. ISBN 0520223942. | ||

| + | * Freedman, Chaim. ''Eliyahu's Branches: The Descendants of the Vilna Gaon (Of Blessed and Saintly Memory) and His Family''. Avotaynu, 1997. ISBN 1886223068. | ||

| + | * Landau, Betzalel and Rosenblum, Yonason. ''The Vilna Gaon: The Life and Teachings of Rabbi Eliyahu, the Gaon of Vilna''. Mesorah Pub., Ltd., 1994. ISBN 0899064418. | ||

| + | *Schochet, Elijah Judah. ''The Hasidic Movement and the Gaon of Vilna''. J. Aronson, 1994. ISBN 9781568211251. | ||

| + | * Shulman, Yaacov Dovid. ''The Vilna Gaon: The Story of Rabbi Eliyahu Kramer''. C.I.S. Publishers, 1994. ISBN 1560622784. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved February 13, 2024. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * [http://www.ou.org/publications/ja/5759winter/leiman.htm Who is Buried in the Vilna Gaon's Tomb?] ''www.ou.org'' | |

| − | + | * [http://www.avotaynu.com/gaontree.html Family tree] ''www.avotaynu.com'' | |

| + | * [http://www.muziejai.lt/Vilnius/zydu_muziejus.en.htm Vilna Gaon Museum] ''www.muziejai.lt'' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Category:writers and poets]] | |

| + | [[Category:religion]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Religious figures]] | ||

| + | [[category:philosophers]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Judaism]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{Credit|209708381}} | {{Credit|209708381}} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:13, 13 February 2024

Elijah ben Solomon, better known as the Vilna Gaon (April 23, 1720 – October 9, 1797), was the foremost intellectual leader of non-Hasidic Jewry in eighteenth century Europe. Among Jews, he is often referred to the The Gra—from the Hebrew acronym "Gaon Rabbi Eliyahu."

Born in Vilnius, Lithuania, the Vilna Gaon displayed extraordinary talent while still a child. By the time he was 20 years old, rabbis were reportedly submitting their most difficult halakhic (Jewish legal) problems to him for rulings. He was also a voluminous author, writing commentaries on virtually all of the classical sources of Jewish legal tradition.

Broad-minded but disciplined in his approach to Talmudic study and ascetic in his lifestyle, the Vilna Gaon pioneered a frank, critical examination of texts. He thus rejected the prevalent pilpul school, which went to great lengths to reconcile apparently contradictory precedents found in Jewish legal texts such as the Mishnah, the Talmud, the Shulchan Aruch, and later rabbinical rulings.

When the fervent enthusiasm of Hasidic Judaism became influential in Vilnius, the usually retiring Vilna Gaon joined with the rabbis who sought to repress Hasidic influence. As a result, one of the first mass excommunications against the Hasidim was launched in Vilnius in 1777. The Vilna Gaon continued persecuting the Hasidim, at intervals, throughout the rest of his life.

In addition to voluminous rabbinical and mystical works, the Vilna Gaon also wrote on mathematics and encouraged his pupil, Rabbi Baruch of Shklov, to translate the works of Euclid into Hebrew. After his death, his primary disciple, Rabbi Chaim Volozhin, founded a yeshiva at Volozhin in 1803, which became a major influence on later Orthodox Jewry. Among non-Hasidic Jews, the Vilna Goan became one of the most influential rabbinic authorities since the Middle Ages. Many Ashkenazi Jewish authorities and yeshivas uphold Jewish customs and rites, known as the minhag ha-Gra, named for him. His followers were also among the first modern Jews to immigrate to the future land of Israel, where his influence continues to be strongly felt.

Youth and education

The Vilna Gaon's given Hebrew name was Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman. The term "Gaon" was an honorific title previously given to heads of major Jewish academies, sometimes translated as "genius." "Vilna" is simply the name of his city of Vilnius, in today's Lithuania. Ironically, the Vilna Gaon never headed a school, although his personal pupils became very influential and gave him the title of Gaon to honor his status as their teacher.

Legend holds that young Elijah be Solomon was a child prodigy who had committed the Hebrew Bible to memory by the age of three. He reportedly possessed a photographic memory. At seven he was taught Talmud by Moses Margalit, the influential rabbi of Kėdainiai. By eight, he was studying astronomy during his free time. From the age of ten, he continued his studies without the aid of a teacher, and at 11 he had reportedly committed the entire Talmud to memory.

By his teens, Elijah's intellectual gifts were already famous. He traveled in various parts of Europe, including Poland and Germany, as was the custom of the pious Jews of the time who could afford to do so. By the time he was 20, rabbis began submitting their most difficult halakhic problems to him. Scholars, both Jewish and non-Jewish, sought his insights into mathematics and astronomy. He returned to his native town of Vilnius/Vilna in 1748, having by then acquired considerable renown.

Methodology and character

The Vilna Gaon applied formal philological methods to study the Talmud and rabbinic literature. A proponent of intellect over emotion, he nonetheless took a broader approach than his predecessors of the pilpul school of Talmudism, which went to great trouble to attempt to reconcile apparent contradictions presented in Jewish legal texts. Instead, he engaged in a rigorous but frank critical examination and was more than willing to confront contradictions; nor was he unwilling at times to overthrow the decisions made by his rabbinic predecessors.

Not content to concentrate on the Talmud and subsequent commentaries alone, the Vilna Gaon devoted much time to the study of the Hebrew Bible and grammar. He was also knowledgeable in the secular sciences. Despite his later opposition to the mysticism of the [[Hasidim, the "Gra" was himself attracted to the study of Kabbalah. He was thus not opposed to mysticism per se, but emphasized the need for Kabbalah to be practiced only within the bounds of Jewish law and on the foundation of disciplined Talmudic study.

The Vilna Gaon rarely took part in public affairs and, so far as is known, did not preside over any school in Vilna. He was satisfied with lecturing in private to a few chosen pupils. He was especially anxious to introduce them to the study of the Hebrew Bible, the midrashic literature, and the Minor Treatises of the Talmud, which were very little known by the scholars of his time. Unlike the other Jewish scholars, the Vilna Gaon also laid special stress on the study of the Jerusalem Talmud—in addition to the Babylonian version—which had been almost entirely neglected for centuries.

The Gra was reportedly very modest and objective in his personal attitude, eschewing both passion and public controversy. Despite his high authority, he declined to accept the office of Vilnius' chief rabbi, although it was often offered to him on the most flattering terms.

His life was an ascetic one, as he interpreted literally the words of certain Jewish sages that the Torah can be truly acquired only by abandoning all pleasures and cheerfully accepting suffering. Although this put him squarely at odds with the joyous, life-affirming tradition of the Hasidim, he was revered by many of his countrymen as a saint, being called by some of his contemporaries "the Hasid," meaning "pious one."

Antagonism to Hasidism

The exception to the rule of the Vilna Gaon's humility and reservation came with regard to the spread of Hasidic Judaism. This movement had grown up in opposition to the dry intellectualism of the prevailing Jewish religious leadership, emphasizing instead a fervent personal relationship with God that made mystical experience more important than formal Talmudic study. When Hasidim became influential in his native Vilnius, the Vilna Gaon joined the Mitnagdim—the rabbis and heads of the neighboring Jewish communities opposed to Hasidism—and took direct steps to check the Hasidic influence.

Under his influence, in 1777 one of the first mass excommunications against the Hasidim was launched in Vilnius. A letter was also addressed to all of the large Jewish communities, exhorting them to deal with the Hasidim following Vilinius' example, and to put the Hasidim under surveillance until they had recanted. The letter was acted upon by several communities, resulting in the Hasidim closing the Hasidic houses of worship and a temporary retreat of their evangelical efforts. According to Chabad tradition, the Hasidic leader the Maggid of Mezeritch sent Rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liadi and Rabbi Menachem Mendel Horodoker to the Vilna Gaon to dialog with him, but the Gaon refused to meet with them.

The persecution thus temporarily drove the Hasidic movement underground, but in 1781, when the Hasidim renewed their proselytizing work under the leadership of Shneur Zalman, the Vilna Gaon excommunicated the Hasidim again, this time publicly declaring them to be heretics with whom no pious Jew might intermarry or associate.

After this, the Gaon went into retirement again, concentrating on his writing and teaching his select pupils. Eventually, a rumor spread he had changed his mind and had even repented of having persecuted the Hasidim. In 1796, the Gaon reacted to this by sending two of his pupils with letters throughout the Jewish communities of Greater Poland, declaring that he had by no means changed his attitude in the matter. Neither the excommunications nor the Gaon's letters, however, could stop the tide of Hasidism, which remained a major trend throughout much of Eastern Europe.

Works

The Vilna Gaon was a voluminous author; there is hardly an ancient Hebrew book of any importance to which he did not write a commentary, or at least provide marginal glosses and notes, which were mostly dictated to his pupils. However, nothing of his was published in his lifetime.

His glosses on the Babylonian Talmud and Shulchan Aruch are known as Biurei ha-Gra ("Elaboration by the Gra"). His running commentary on the Mishnah is titled Shenoth Eliyahu ("The Years of Elijah"). Various kabbalistic works also have commentaries in his name. His insights on the Pentateuch are titled Adereth Eliyahu ("The Splendor of Elijah"). Later in his life, he also wrote commentaries on the Proverbs and other books of the Hebrew Bible.

The Vilna Gaon also wrote on mathematics, being well versed in the works of Euclid and encouraging his pupil Rabbi Baruch of Shklov to translate the great mathematician's works into Hebrew.

Legacy

After his death in 1797, aged 77, the Vilna Gaon was buried in the Šnipiškės cemetery in Vilnius. The cemetery was closed by the tsarist Russian authorities in 1831 and partly built over. In the 1950s, Soviet authorities planned to build a stadium and concert hall on the site. They allowed the remains of the "Gra" to be removed and re-interred at the new cemetery.

The Vilna Gaon was one of the most influential rabbinic authorities since the Middle Ages. Many yeshivas today uphold the set of customs that can be traced back to him, known as the minhag ha-Gra. His main student, Rabbi Chaim Volozhin, founded the first yeshiva in his home town of Volozhin, Belarus. The results of this move revolutionized Torah study and are still felt throughout much of Orthodox Judaism today.

In accordance with the Vilna Gaon's wishes, three groups of his disciples and their families, numbering over 500, immigrated to the Land of Israel between 1808 and 1812. This movement is considered by some to be the beginning of the modern Jewish settlement of Israel. As a result of this movement, the teachings of the Vilna Gaon have had a considerable influence on Jewish thought and religious practice among the Ashkenazi community in Israel.

There is a statue of the Vilna Gaon and a street named after him in the central city of Vilnius, the place of both his birth and his death.

See also

- Orthodox Judaism

- Hasidic Judaism

- Mitnagdim

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ackerman, C.D. (trans.). Even Sheleimah: The Vilna Gaon Looks at Life. Targum Press, 1994. ISBN 0944070965.

- Etkes, Immanuel, et al. The Gaon of Vilna: The Man and His Image. University of California Press, 2002. ISBN 0520223942.

- Freedman, Chaim. Eliyahu's Branches: The Descendants of the Vilna Gaon (Of Blessed and Saintly Memory) and His Family. Avotaynu, 1997. ISBN 1886223068.

- Landau, Betzalel and Rosenblum, Yonason. The Vilna Gaon: The Life and Teachings of Rabbi Eliyahu, the Gaon of Vilna. Mesorah Pub., Ltd., 1994. ISBN 0899064418.

- Schochet, Elijah Judah. The Hasidic Movement and the Gaon of Vilna. J. Aronson, 1994. ISBN 9781568211251.

- Shulman, Yaacov Dovid. The Vilna Gaon: The Story of Rabbi Eliyahu Kramer. C.I.S. Publishers, 1994. ISBN 1560622784.

External links

All links retrieved February 13, 2024.

- Who is Buried in the Vilna Gaon's Tomb? www.ou.org

- Family tree www.avotaynu.com

- Vilna Gaon Museum www.muziejai.lt

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.