Dixieland

Dixieland music is an early style of jazz which developed in New Orleans at the start of the twentieth century, and spread to Chicago and New York City by New Orleans bands in the 1910s. Dixieland jazz combined brass band marches, French Quadrilles, ragtime and blues with collective, polyphonic improvisation by trumpet (or cornet), trombone, and clarinet over a "rhythm section" of piano, guitar, banjo, drums, and a double bass or tuba. As an American stylism, dixieland music incorporated the cultural aspects of New Orleans jazz music of the early twentieth century. It combined French quadrilles, ragtime and blues to inculcate a new form of jazz which leaped boundaries towards a harmony and cooperation beyond the divisions of nationality, religion, race and ethnicity.

History

Origins

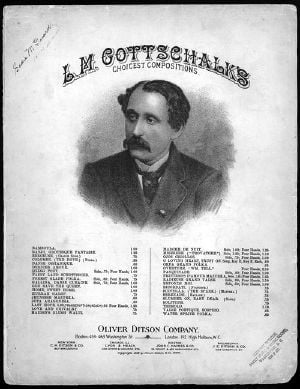

The music of American-Creole composer Louis Moreau Gottschalk (1829-1869) included some of the earliest examples of the type of syncopation that would eventually become the hallmark of ragtime, Dixieland and jazz. As Gottschalk's biographer, Frederick Starr, points out, these rhythmic elements "anticipate ragtime and jazz by a half century."

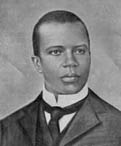

Ragtime composers such as James Reese Europe and Scott Joplin were influenced greatly by Gottschalk's music. Europe's Clef Club Orchestra and Hell Fighters Band, and Will Marion Cook's Southern Syncopated Orchestra were ensembles that made important contributions in the evolution of ragtime and Dixieland.

The early Dixieland style combined brass band marches, French Quadrilles, ragtime and blues with collective, polyphonic improvisation. While the instrumentation and size of bands can be very flexible, the "standard" band consists of a "front line" of trumpet (or cornet), trombone, and clarinet, with a "rhythm section" of at least two of the following instruments: guitar or banjo, string bass or tuba, piano, and drums.

Heyday

The term Dixieland became widely used after the advent of the first million-selling hit records of the Original Dixieland Jass Band in 1917. The music has been played continuously since the early part of the twentieth century. Louis Armstrong's All-Stars was the band most popularly identified with Dixieland, although Armstrong's own influence runs through all of jazz.

As Dixieland Jazz evolved and moved to St. Louis, Detroit, and Chicago it changed and took on different musical characteristics. Bix Beiderbecke, cornetist, composer and pianist, was a key figure in making soloing a fixture of Dixieland Jazz. Armstrong (who admired Beiderbecke's playing) and others, expanded on Beiderbecke's idea making solo improvisation a common practice of the genre. Also, Dixieland evolved into a more driving rhythmic style.

Many Dixieland groups consciously imitated the recordings and bands of decades earlier. Other musicians continued to create innovative performances and new tunes. The definitive Dixieland sound is created when one instrument (usually the trumpet) plays the melody or a recognizable paraphrase or variation on it, and the other instruments of the "front line" improvise around that melody. This creates a more chaotic sound than the extremely regimented big band sound or the unison melody of bebop.

Later trends

The swing era of the 1930s led to the end of many Dixieland musicians' careers. Only a few musicians were able to maintain popularity, and most retired.

With the advent of bebop in the 1940s, the earlier group-improvisation style fell out of favor with the majority of younger black players, while some older players of both races continued on in the older style. Though younger musicians developed new forms, many beboppers revered Armstrong, and quoted fragments of his recorded music in their own improvisations.

There was a revival of Dixieland in the late 1940s and 1950s, which brought many semiretired musicians a measure of fame late in their lives as well as bringing retired musicians back onto the jazz circuit after years of not playing (e.g. Kid Ory). This period is sometimes seen as a fad.

In the 1950s a style called "Progressive Dixieland" sought to blend traditional Dixieland melody with bebop-style rhythm. Steve Lacy played with several such bands early in his career. This style is sometimes called "Dixie-bop."

Some fans of post- bebop jazz consider Dixieland no longer to be a vital part of jazz, while some adherents consider music in the traditional style, when well and creatively played, every bit as modern as any other jazz style.

Terminology

While the term Dixieland is still in wide use, the term's appropriateness is a hotly debated topic in some circles. For some it is the preferred label (especially bands on the USA's West coast and those influenced by the 1940s revival bands), while others (especially New Orleans musicians, and those influenced by the African-American bands of the 1920s) would rather use terms like Classic Jazz or Traditional Jazz. Some of the latter consider Dixieland a derogatory term implying superficial hokum played without passion or deep understanding of the music.

According to jazz writer Gary Giddins, the term Dixieland was widely understood in the early twentieth century as a code for "black music." Frequent references to Dixieland were made in the lyrics of popular songs of this era, often written by songwriters of both races who had never been south of New Jersey. Other composers of the "Dixieland" standards, such as Clarence Williams and Jelly Roll Morton, were native New Orleanians.

Dixieland is often today applied to white bands playing in a traditional style. Some critics regard this labeling as incorrect. From the late 1930s on, black and mixed-race bands playing in a more traditional group-improvising style were referred to in the jazz press as playing "small-band Swing," while white and mixed-race bands such as those of Eddie Condon and Muggsy Spanier were tagged with the Dixieland label.

This brings us back to the fundamentally problematic character of the term Dixieland as a musical category. There are black musicians today, young as well as old, who play New Orleans jazz, traditional jazz, or small band swing that musically could also be called Dixieland, although black musicians often reject the term. Thus it makes sense to say only white musicians play Dixieland. In the early 20th century, Dixieland may have been understood as a code for black music in the northern US. However, in New Orleans the distinction was as clear then as now. It is sometimes said that only white bands were called Dixieland bands, like the Original Dixieland Jazz Band. A number of early black bands used the term Creole (as with King Oliver's Creole Jazz Band), including some that were not actually ethnic Creoles.

Younger generations of primarily white players continued to find inspiration in the spirited, highly rhythmic traditional style of playing, with the result that the ranks of African-Americans today playing in the Dixieland style of jazz are very few. However, this has to be understood with the recognition that Dixieland jazz is as much a social/racial category as it is a musical one, unlike the more specifically musical New Orleans jazz or Traditional jazz. In these latter categories there are plenty of active young black musicians. The upshot of this is that although Dixieland is a term used to mean "traditional jazz" outside of jazz, within jazz it is a white subset of traditional jazz.

Modern Dixieland

Today there are three main active streams of Dixieland jazz:

Chicago style

"Chicago style" is often applied to the sound of Chicagoans such as Eddie Condon, Muggsy Spanier, and Bud Freeman. The rhythm sections of these bands substitute the string bass for the tuba and the guitar for the banjo. Musically, the Chicagoans play in more of a swing-style 4-to-the-bar manner. The New Orleanian preference for an ensemble sound is deemphasized in favor of solos. Chicago-style dixieland also differs from its southern origin by being faster paced, resembling the hustle-bustle of city life. Chicago-style bands play a wide variety of tunes, including most of those of the more traditional bands plus many of the Great American Songbook selections from the 1930s by George Gershwin, Jerome Kern, Cole Porter, and Irving Berlin. Non-Chicagoans such as Pee Wee Russell and Bobby Hackett are often thought of as playing in this style. This modernized style came to be called Nicksieland, after Nick's Greenwich Village night club, where it was popular. though the term was not limited to that club.

West Coast revival

The "West Coast revival" is a movement begun in the late 1930s by the Lu Watters Yerba Buena Jazz Band of San Francisco and extended by trombonist Turk Murphy. It started out as a backlash to the Chicago style, which is closer in development towards swing. The repertoire of these bands is based on the music of Joe "King" Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, Louis Armstrong, and W.C. Handy. Bands playing in the West Coast style use banjo and tuba in the rhythm sections, which play in a 2-to-the-bar rhythmic style. Watters was fixated on reproducing the recorded sound of King Oliver's band with Armstrong on second cornet. Since the Oliver recordings were acoustic, they had no drums, so Watters omitted the drums as well, even though Oliver had drums when he played live.

New Orleans Traditional

The "New Orleans Traditional" revival movement began with the rediscovery of Bunk Johnson in 1942 and was extended by the founding of Preservation Hall in the French Quarter during the 1960s. Bands playing in this style use string bass and banjo in the rhythm section playing 4-to-the-bar and feature popular tunes and Gospel hymns that were played in New Orleans since the early 20th century such as "Ice Cream," "You Tell Me Your Dream," "Just a Closer Walk With Thee" and some tunes from the New Orleans brass band literature. The New Orleans "revival" of the 1960s added a greater number of solos, in a style influenced by mid-century New York Dixieland combos, as this was less of a strain on some musicians of advanced years than the older New Orleans style with much more ensemble playing.

There are also active traditionalist scenes around the world, especially in Britain and Australia.

Famous traditional Dixieland tunes include: "When the Saints Go Marching In," "Muskrat Ramble," "Struttin' With Some Barbecue," "Tiger Rag," "Dippermouth Blues," "Milneburg Joys," "Basin Street Blues," "Tin Roof Blues," "At the Jazz Band Ball," "Panama," "I Found a New Baby," "Royal Garden Blues" and many others. All of these tunes were widely played by jazz bands of both races of the pre-WWII era, especially Louis Armstrong. They came to be grouped as Dixieland standards beginning in the 1950s.

Partial List of Dixieland musicians

Some of the artists historically identified with Dixieland are mentioned in List of jazz musicians.

Some of the best-selling and famous Dixieland artists of the post-WWII era:

- Tony Almerico, trumpeter, played Dixieland live on clear channel WWL radio in New Orleans, as well as at many downtown hotels, and was a tireless promoter of the music.

- Kenny Ball, had a top-40 hit with "Midnight in Moscow" in the early 1960s. From Britain.

- Eddie Condon, guitarist and banjo player and a leading figure in the Chicago style of Dixieland. He led bands and ran a series of nightclubs in New York City and had a popular radio series.

- [Jim Cullum]], cornetist based in San Antonio, TX. With his late father, led bands in San Antonio since 1963, originally known as the Happy Jazz Band.

- Ron Dewar, who in the 1970s revitalized the Chicago traditional jazz scene with his short-lived but influential band The Memphis Nighthawks.

- The Dukes of Dixieland, the Assunto family band of New Orleans. A successor band continues on in New Orleans today.

- Pete Fountain, clarinetist who led popular bands in New Orleans, retired recently.

- Al Hirt, trumpeter who had a string of top-40 hits in the 1960s, led bands in New Orleans until his death.

- Ward Kimball, leader of the Firehouse Five Plus Two.

- Tim Laughlin, clarinetist, protege of Pete Fountain, who has led many popular bands in New Orleans, and often tours in Europe during the summer.

- Turk Murphy, a trombonist who led a band at Earthquake McGoons and other San Francisco venues from the late 1940s through the 1970s.

- Chris Tyle, cornetist, trumpeter, drummer, clarinetist, saxophonist, leader of the Silver Leaf Jazz Band. Also known as a jazz writer and educator. A member of the International Associate of Jazz Educators and the Jazz Journalists Assn.

Festivals and periodicals

- The enormously famous New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival features jazz and many other genres by local, national, and internationally known artists.

- In Dresden, Germany, Dixieland is the name of Europe's biggest international jazz festival. 500,000 visitors celebrate it mainly on the river. A smaller festival, called "Riverboat Jazz Festival" is held annually in the picturesque Danish town of Silkeborg.

- In the US, the largest traditional jazz festival, the Sacramento Jazz Jubilee, is held in Sacramento, CA annually on Memorial Day weekend, with about 100,000 visitors and about 150 bands from all over the world. Other smaller festivals and jazz parties arose in the late 1960s as the rock revolution displaced many of the jazz nightclubs.

- In Tarragona, Catalonia, Spain's only dixieland festival has been held annually the week before Easter, since 1994, with 25 bands from all over the world and 100 performances in streets, theatres, cafés and hotels.[1]

Periodicals

There are several active periodicals devoted to traditional jazz: The Mississippi Rag, the Jazz Rambler, and the American Rag published in the US; and Jazz Journal International published in Europe.

Impact of dixieland music

Musical styles with important influence from Dixieland or Traditional Jazz include Swing music, some Rhythm & Blues and early Rock & Roll also show significant trad jazz influence, Fats Domino being an example. The contemporary New Orleans Brass Band styles, such as the Dirty Dozen Brass Band, The Primate Fiasco, the Hot Tamale Brass Band and the Rebirth Brass Band have combined traditional New Orleans brass band jazz with such influences as contemporary jazz, funk, hip hop, and rap.

These composers and musicians used the Dixieland style as a springboard in bringing such musical innovations to a regional genre. They placed New Orleans on a musical map to influence other areas of the United States as well as Europe, Asia, and the Americas.

James Reese Europe's Clef Club Orchestra was the first jazz band to play at Carnegie Hall in 1912. It is hard to overstate the importance of that event in the history of jazz in the United States. It was twelve years before the Paul Whiteman and George Gershwin concert at Aeolian Hall and twenty-six years before Benny Goodman's famed concert at Carnegie Hall. In the words of American composer and conductor, Gunther Schuller, Europe "…had stormed the bastion of the white establishment and made many members of New York's cultural elite aware of Negro music for the first time." The concert had social and cultural implications as white society began to explore music of black musicians with greater interest.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brunn, Harry O., The story of the Original Dixieland Jazz Band, Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1960. OCLC 610906

- Gilbert, Peggy; Dixie Belles, Dixieland jazz, Lomita, CA: Cambria Records, 2006. OCLC 141659500

- Williams, Martin T., The art of jazz: essays on the nature and development of jazz, NY: Oxford University Press, 1959. OCLC 611460

- Young, Kevin, Dixieland, Project Muse, 2001. OCLC 88347214

- Starr, S. Frederick. "Bamboula!: The Life and Times of Louis Moreau Gottschalk," New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. ISBN 0-195-07237-5

- Badger, F. Reed. A Life in Ragtime: A Biography of James Reese Europe. Oxford University Press, 1995. ISNB-0195-06044-X

External links

- Dixieland Jazz - john p birchall Retrieved October 21, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.