Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation

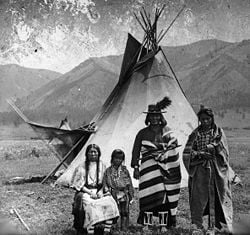

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation are the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai and Pend d'Oreilles Tribes. There is also the Chinook tribe. The Flatheads lived between the Cascade Mountains and Rocky Mountains. The Salish (Flatheads) initially lived entirely east of the Continental Divide but established their headquarters near the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains. Occasionally hunting parties went west of the Continental Divide but never east of the Bitterroot Range. The easternmost edge of their ancestral hunting forays were the Gallatin, Crazy Mountain, and Little Belt Ranges.

They were called the Flathead Indians by the first white men who came to the Columbia River. The name is often said to derive from the flat skull produced by binding infant's skulls with boards. However, this is mistaken folk etymology, as the tribes never practiced head flattening. In fact, the Salish were called "flat head" because the tops of their heads were not pointed like those of neighboring tribes people who practiced vertical head-binding. The sign language used by neighboring tribes to distinguish the Flatheads consisted of "pressing each side of the head" with the hands. The Flatheads call themselves Salish meaning the people.

History

The written record of the tribes is from their meeting with the Lewis and Clark Expedition (September 5, 1805). Lewis and Clark came there and bought horses but eventually ate the horses because of starvation. The Flatheads also appear in the records of the Catholic Church at St. Louis to which they sent four delegations to request missionaries (or "Black Robes") to minister to the tribe. Their request was finally granted and a number of missionaries including Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J., were eventually sent.

The tribes negotiated the Treaty of Hellgate with the United States in 1855. From the start, the Hellgate Treaty negotiations were plagued by serious translation problems. A Jesuit observer, Father Adrian Hoecken, said that the translations were so poor that "not a tenth of what was said was understood by either side." But as in the meeting with Lewis and Clark, the pervasive cross-cultural miscommunication ran even deeper than problems of language and translation. Tribal people came to the meeting assuming they were going to formalize an already-recognized friendship. Non-Indians came with the goal of making official their claims to native lands and resources. Isaac Stevens, the new governor and superintendent of Indian affairs for Washington Territory, was intent on obtaining cession of the Bitterroot Valley from the Salish. Many non-Indians were already well aware of the valley's potential value for agriculture and its relatively temperate climate in winter. Due to the resistance of Chief Victor (Many Horses), Stevens ended up inserting into the treaty complicated (and doubtless poorly translated) language that defined the Bitterroot Valley south of Lolo Creek as a "conditional reservation" for the Salish. Chief Victor put his X mark on the document, convinced that the agreement would not require his people to leave their homeland. No other word came from the government for the next fifteen years, so the Salish assumed that they would indeed stay in their Bitterroot Valley forever.

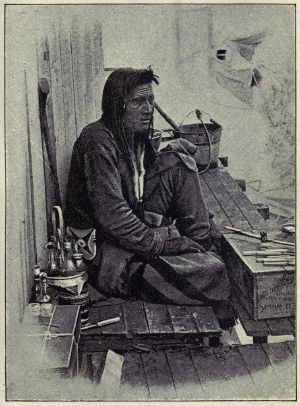

After the 1864 gold rush in newly established Montana Territory, pressure upon the Salish intensified from both illegal non-Indian squatters and government officials. In 1870, Chief Victor died, and he was succeeded as chief by his son, Chief Charlot (aka Charlo, Claw of the Little Grizzly). Like his father, Chief Charlot adhered to a policy of nonviolent resistance. He insisted on the right of his people to remain in the Bitterroot Valley. But territorial citizens and officials thought the new chief could be pressured into capitulating. In 1871, they successfully lobbied President Ulysses S. Grant to declare that the survey required by the treaty had been conducted and that it had found that the Jocko (Flathead) Reservation was better suited to the needs of the Salish. On the basis of Grant's executive order, Congress sent a delegation, led by future president James Garfield, to make arrangements with the tribe for their removal. Chief Charlot ignored their demands and even their threats of bloodshed, and he again refused to sign any agreement to leave. U.S. officials then simply forged Chief Charlot's X onto the official copy of the agreement that was sent to the Senate for ratification.

Over time, the real reason for the Hellgate treaty meetings became clear to the Salish and Pend d'Oreille people. Under the terms spelled out in the written document, the tribes ceded to the United States more than twenty million acres (81,000 km²) of land and reserved from cession about 1.3 million acres (5300 km²), thus forming the Jocko or Flathead Indian Reservation. Conditions had become intolerable for the Salish by the late 1880s, after the Missoula and Bitter Root Valley Railroad was constructed directly through the tribe's lands, with neither permission from the native owners nor payment to them. Chief Charlot finally signed an agreement to leave the Bitterroot Valley in November 1889. Inaction by Congress, however, delayed the removal for another two years, and according to some observers, the tribe's desperation reached a level of outright starvation. In October 1891 a contingent of troops from Fort Missoula forced Chief Charlot and the Salish out of the Bitterroot and roughly marched the small band sixty miles to the Flathead Reservation.

The three main tribes moved to the Flathead Reservation were the Bitteroot Salish, Pend d'Oreille, and Kootenai. The Bitterroot Salish and the Pend Oreille tribes spoke dialects of the same Salish language.

Bitteroot Salish

The Bitterroot Salish are one of three tribes of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation in Montana. The Flathead Reservation is home to the Kootenai and Pend d'Oreilles tribes also.

The people are a Salish speaking group of Native Americans.

Pend d'Oreilles

The Pend d'Oreilles, also known as the Kalispel, are a tribe of Native Americans who lived centered around Lake Pend Oreille, as well as the Pend Oreille River, and Priest Lake although some of them live spread throughout Montana and eastern Washington. The primary tribal range from roughly Plains, Montana westward along the Clark Fork River, Lake Pend Oreille in Idaho, and the Pend'Oreille River in Eastern Washington and into British Columbia was given the name Kaniksu by the Kalispel peoples. The Kalispel are one of the three tribes of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation.

The name Pend Oreille is of French origin, meaning "hangs from ears," which refers to the large shell earrings that these people wore. The main part of the reservation on which these Native Americans live is northwest of Newport, Washington, in central Pend Oreille County. The main reservation is an 18.638 km² (7.196 sq mi) strip of land along the Pend Oreille River, west of the Washington-Idaho border. There is also a small parcel of land in the western part of the Spokane metropolitan area in the city of Airway Heights, with a land area of 0.202 km² (49.92 acres), currently the site of Northern Quest Casino which is operated by the tribe. The total land area of the Kalispel Indian Reservation is 18.840 km² (7.274 sq mi).

The Pend d'Oreilles were generally peaceable. These people made their weapons and tools from flint, and many other things were shaped with rocks. For housing the Pend d'Oreilles lived in tipis in the summer, as well as lodges in the winter time. These houses were all built out of large cattails, which were in abundance where the people lived. These cattails were woven into mats called "tule mats" which were attached to a tree branch frame to form a hut. Today a large community building on the Kalispel reservation retains the name "Tule Hut" in remembrance of this traditional housing.

The horses the Native Americans needed came from trading buffalo skins. The Pend d'Oreilles, like many other tribes, hunted buffalo and traded the furs for other useful goods. These people wore robes as well as skins for clothing. They decorated themselves with dyes, paints, beads, and sometimes even animal quills.

Their language, Kalispel-Pend d'Oreille, belongs to the Salishan family.

Kootenai

The Kootenai (also spelled Kutenai) or Ktunaxa (pronounced in English as /k.tuˈnæ.hæ/) are an indigenous people of North America. They are one of three tribes of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation in Montana, and they form the Ktunaxa Nation in British Columbia. There are also populations in Idaho and Washington in the United States.[1] The Flathead Reservation is home to the Bitterroot Salish and Pend d'Oreilles tribes as well.

The tribes constitute a distinct stock (Kitunahan). There is evidence that they formerly lived in the eastern plains and were driven into the mountains by the Blackfeet.

Originally the tribe is said to have lived in the plains, east of the Rockies, but were driven out by the Blackfoot.[2]

On September 21, 1975, the Kootenai Tribe headed by Chairwoman Amy Trice declared war on the United States government. Their first act was to post soldiers on each end of the highway that runs through the town and they forced people, at gunpoint, to pay a toll to drive through the land that had been the tribe’s aboriginal land. The money would be used to house and care for elderly tribal members. Most tribes in the United States are forbidden to declare war on the U.S. government because of treaties, but the Kootenai Tribe never signed a treaty. The dispute resulted in the concession by the United States government and a land grant of 12.5 acres (51,000 m²) that would become what is now the Kootenai Reservation.[3] In 1976 the tribe issued "Kootenai Nation War Bonds" that sold at $1.00 each. The bonds were dated 20 September, 1974 and contained a brief declaration of war on the United States. These War Bonds were signed by Amelia Custack Trice, Tribal Chairwoman and Douglas James Wheaton, Sr., Tribal Representative. The bonds themselves were printed on heavy paper stock and were created and signed by well known Western Artist, Emilie Touraine.

The Ktunaxa are members of seven bands or nations, five of which are in British Columbia, Canada and two are in the United States.[4]

Kootenai Indian Reservation

The Kootenai Indian Reservation lies in central Boundary County, Idaho, about 40 km south of the Canadian border, and about 3 km west-northwest of the city of Bonners Ferry. It has a land area of only 0.076575 km² (18.922 acres) and a 2000 census resident population of 75 persons.

Geography

Aboriginal Lands

The peoples of these tribes originally lived in the areas of Montana, parts of Idaho, British Columbia and Wyoming. The original territory comprised about 22 million acres (89,000 km²) at the time of the 1855 Hellgate Treaty.

Reservation lands

The Flathead Reservation in northwest Montana is over 1.3 million acres (5,300 km²) in size.

The Flathead Indian Reservation, located in western Montana on the Flathead River, is home to the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai and Pend d'Oreilles Tribes - also known as the

Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation (1). The Reservation was created through 1855 Treaty of Hellgate and includes parts of four Montana counties: Lake, Sanders, Missoula, and Flathead (2). The Flathead Indian Reservation is an area of 5,019.621 km² (1,938.087 sq mi) of forested mountains and valleys just west of the Continental Divide (3).

Unlike most other tribes in Montana, the Bitterroot Salish migrated from the west. The Kootenai, however, are native to the state. Archaeological evidence shows that native Americans inhabited Montana more than 14,000 years ago, and artifacts indicate that the Kootenai have roots in the area's prehistory. The Kootenai inhabited the mountainous terrain west of the Continental Divide, venturing only seasonally to the east for buffalo hunts. The Kootenai were divided into two main groups. One band lived to the northeast and had a lifestyle based on buffalo hunting. The other band lived in the mountainous west and had a lifestyle focused on rivers and lakes. The Salish occupied territory in Washington, Idaho, and western Montana but ventured as far east as the Bighorn Mountains. As the tribe moved east, it had to change from a lifestyle based on salmon fishing to one more dependent on native plants and buffalo. During the 1700s, these two tribes – the Salish and the Kootenai – shared common hunting and gathering grounds (4).

Contemporary Flathead Indians

The tribe has about 6,800 members with approximately 4,000 tribal members currently living on the Flathead Reservation and 2,800 tribal members living off the reservation. Their predominant religion is Roman Catholic. 1,100 Native Americans from other tribes and over 10,000 non-Native Americans also live on the reservation.

As the first to organize a tribal government under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1936 the tribes are governed by a tribal council. The Tribal Council has ten members and the council elects from within the Chairman, Vice Chairman, Secretary and Treasurer. The tribal government offers a number of services to tribal members and is the chief employer on the reservation. The tribes operate a tribal college, the Salish Kootenai College and a heritage museum called "The People's Center" in Pablo, seat of the tribal government.

The tribes own and jointly operate a valuable hydropower dam called Kerr Dam as well as the Best Western KwaTaqNuk Inn in Polson, county seat of Lake County and most populous community on the reservation.

The present-day population of the Flathead Indian Reservation is 26,172 as of the 2000 census. The largest community on the reservation is the city of Polson, which is also the county seat of Lake County. The seat of government of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation is Pablo.

Salish Kootenai College (SKC) is a Native American tribal college based in Pablo, Montana which serves the Bitterroot Salish, Kootenai, and Pend d'Oreilles tribes. There are approximately 1,100 students attending the college; enrollment is not limited to Native American students.

Prior to 1978, it was a branch campus of Flathead Valley Community College (FVCC). In 1981, the college formally disassociated itself from FVCC and became completely self-governing. It is member of the American Indian Higher Education Consortium.

SKC offers 7 Bachelor's degree programs, 13 Associate degree programs, and 7 certificate programs. Most of the degree programs are career-oriented, though students can elect to take courses of study in fields such as the liberal arts and Native American Studies.

Notes

- ↑ Kootenai Reservation, Idaho United States Census Bureau

- ↑ [[wikisource:Catholic Encyclopedia (1913)/Kutenai Indians "|Kutenai Indians]".] Catholic Encyclopedia. (1913). New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ↑ Idaho’s forgotten war

- ↑ Who We Are - Ktunaxa Nation

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bigart, Robert, and Clarence Woodcock. In the Name of the Salish & Kootenai Nation: The 1855 Hell Gate Treaty and the Origin of the Flathead Indian Reservation. Pablo, Mont: Salish Kootenai College Press, 1996. ISBN 0295975458

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. Ktunaxa Legends. Pablo, Mont: Salish Kootenai College Press, 1997. ISBN 0295976608

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. The Salish People and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005. ISBN 0803243111

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation. A Brief History of the Flathead Tribes. St. Ignatius, Mont: Flathead Culture Committee, Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes, 1979.

- Johnson, Olga Weydemeyer. Flathead and Kootenay; The Rivers, the Tribes, and the Region's Traders. Northwest historical series, 9. Glendale, Calif: A. H. Clark Co, 1969.

- Kalispel Reservation, Washington United States Census Bureau

- Curtis, Edward S. "Kalispel," The North American Indian, Volume 7, 51. Northwestern University, Digital Library Collections, 2003 (original 1911, Norwood, MA: The Plimpton Press). Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- Boas, Franz, and Alexander Francis Chamberlain. Kutenai Tales. Washington: Govt. Print. Off, 1918.

- Chamberlain, Alexander Francis. "Report of the Kootenay Indians of South Eastern British Columbia," in Report of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, (London, 1892)

- Finley, Debbie Joseph, and Howard Kallowat. Owl's Eyes & Seeking a Spirit: Kootenai Indian Stories. Pablo, Mont: Salish Kootenai College Press, 1999. ISBN 0917298667

- Linderman, Frank Bird, and Celeste River. Kootenai Why Stories. Lincoln, Neb: University of Nebraska Press, 1997. ISBN 0585315841

- Maclean, John. Canadian Savage Folk, (Toronto, 1896)

- Tanaka, Béatrice, and Michel Gay. The Chase: A Kutenai Indian Tale. New York: Crown, 1991. ISBN 0517586231

- Turney-High, Harry Holbert. Ethnography of the Kutenai. Menasha, Wis: American Anthropological Association, 1941.

- Beaverhead, Pete, and Dwight Billedeaux. 2000. Mary Quequesah's Love Story: A Pend D'Oreille Indian Tale. Pablo, MT: Salish Kootenai College Press. ISBN 0917298713

- Boas, Franz. 1917. Folk-tales of Salishan and Sahaptin Tribes. Published for the American Folk-Lore Society by G.E. Stechert & Co. Available online through the Washington State Library's Classics in Washington History collection. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- Carriker, Robert C. 1973, The Kalispel People. Phoenix AZ: Indian Tribal Series.

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation. 1996. Names Upon the Land, a Tribal Geography of the Salish and Pend D'Oreille People. Pablo, MT: The Committee.

- Fahey, John. 1986. The Kalispel Indians. [Civilization of the American Indian series, v. 180]. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806120002

- Lacy, Thomas F. 1994. Kaniksu, Stories of the Northwest. Keokee Company Publishing.

- Mooney, James. 1909. "Flathead Indians." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 6. New York, NY: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- Mooney, James. 1910a. "Kalispel Indians." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York, NY: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- Mooney, James. 1910b. "Kutenai Indians." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York, NY: Robert Appleton Company. Retrieved December 10, 2008.

- United States Census Bureau Flathead Reservation, Montana, Census 2000 Summary File. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- United States Census Bureau Kootenai Reservation, Idaho, Census 2000 Summary File. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

- Andrews, Leah. Idaho's Forgotten War] Idaho Natives. Retrieved December 16, 2008.

External links

- Official site of Nkwusm Salish Language Institute

- Treaty of Hellgate (1855)

- Lewis and Clark expedition journal entry

- Confederated Tribes of the Salish and Kootenai Tribes

- Char Koosta News

- Charlo School - Local & Social Services

- Online Highways - Flathead Indian Reservation

- montanakids.com - Flathead Indian Reservation

- Access Montana Ronan.net

- Salish Kootenai College

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Confederated_Salish_and_Kootenai_Tribes_of_the_Flathead_Nation history

- Flathead_Indian_Reservation history

- Salish_Kootenai_College history

- Bitterroot_Salish_(tribe) history

- Pend_d'Oreilles_(tribe)256701086 history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.