Columbia River

| Columbia River | |||

|---|---|---|---|

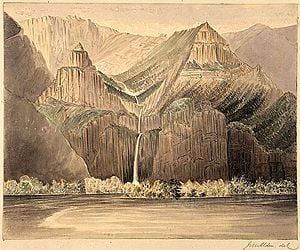

Columbia River near Revelstoke, British Columbia

| |||

| Countries | Canada, United States | ||

| States | Washington, Oregon | ||

| Provinces | British Columbia | ||

| Major cities | Revelstoke, British Columbia, Wenatchee, WA, Tri-Cities, WA, Portland, OR | ||

| Length | 1,243 miles (2,000 km) [1] | ||

| Watershed | 258,000 miles² (668,217 km²) | ||

| Discharge | mouth | ||

| - average | 265,000 feet³/sec. (7,504 meters³/sec.) [2] | ||

| - maximum | 1,240,000 feet³/sec. (35,113 meters³/sec.) | ||

| - minimum | 12,100 feet³/sec. (343 meters³/sec.) | ||

| Source | Columbia Lake | ||

| - location | British Columbia, Canada | ||

| - coordinates | 50°13′N 115°51′W [3] | ||

| - elevation | 2,650 feet (808 meters) [4] | ||

| Mouth | Pacific Ocean | ||

| - coordinates | coord}}{{#coordinates:46|14|39|N|124|3|29|W|landmark | name=

}} [5] | |

| - elevation | 0 feet (0 meters) | ||

| Major tributaries | |||

| - left | Kootenay River, Pend Oreille River, Spokane River, Snake River, Deschutes River, Willamette River | ||

| - right | Okanogan River, Yakima River, Cowlitz River | ||

The Columbia River (French: fleuve Columbia) is a river in the Pacific Northwest region of North America. It stretches from the Canadian province of British Columbia, through the U.S. state of Washington, and forms much of the border between Washington and Oregon before emptying into the Pacific Ocean.

It is the largest river by volume flowing into the Pacific from the Western Hemisphere, and is the fourth-largest by volume in North America behind the Mississippi, St. Lawrence, and Mackenzie Rivers. (In rare years, the river’s flow may actually exceed that of the Mississippi.) The Columbia's average annual flow is about 265,000 ft³/s (7,500 m³/s). The highest recorded flow was 1,240,000 ft³/s (35,113 m³/s), on June 6, 1894. From its headwaters to the Pacific Ocean it flows 1,243 miles (2,000 km), and drains 258,000 square miles (668,217 km²), of which about 15% is in Canada.

The Columbia is the largest hydroelectric power producing river in North America, with 14 hydroelectric dams in the United States and Canada.

The river was named after Captain Robert Gray’s ship Columbia Rediviva, the first ship from the United States or a European country documented to have traveled up the river.[6]

Because of its large water volume and relatively steep grade, the river has the nickname the Mighty Columbia.

Geography

Columbia Lake (elevation about 808 metres or 2,650 ft) forms the Columbia’s headwaters in the Canadian Rockies of southern British Columbia. For its first 200 miles (320 km) the Columbia flows northwest, through Windermere Lake (British Columbia) and the town of Invermere, British Columbia, then northwest to Golden, British Columbia and into Kinbasket Lake. The river then turns sharply south (at the “Big Bend”), passing through Revelstoke Lake and the Arrow Lakes to the BC–Washington border.

The Clark Fork River, which begins near Butte, Montana, flows through western Montana before entering Pend Oreille Lake. Water draining from the lake forms the Pend Oreille River, which flows across the Idaho panhandle to Washington’s northeastern corner where it meets the northern Canadian fork.

The river then winds through the eastern Washington, flowing to the southwest and then changing to a southeasterly direction near the confluence of the Wenatchee River in central Washington. The river continues southeast, past The Gorge Amphitheatre (a prominent concert venue in the Northwest), and then past the Hanford Nuclear Reservation, before meeting the Snake River in the Tri-Cities, Washington. This part of the river, called the Hanford Reach, is the only American stretch of the river that is free-flowing, unimpeded by dams and not a tidal estuary.

The Columbia makes a sharp bend to the west where it meets the state of Oregon. The river forms the border between Washington and Oregon for the final 300 miles (480 km) of its journey.

The river is the only one to pass through the Cascade Mountains, which it does between The Dalles, Oregon and Portland, Oregon, forming the Columbia River Gorge. The gorge is known for its strong steady winds, its scenic beauty, and as an important transportation link.

The river continues west with one small north-northwesterly-directed stretch near Portland, Vancouver, Washington, and the river's confluence with the Willamette River. On this sharp bend the river’s flow slows considerably, and it drops the sediment that might otherwise form a river delta. The river empties into the Pacific Ocean near Astoria, Oregon; the Columbia River sandbar is widely considered one of the most difficult to navigate.

Missoula Floods

During the last Ice Age, a finger of the Cordilleran ice sheet crept southward into the Idaho Panhandle, blocking the Clark Fork River and creating Glacial Lake Missoula. As the waters rose behind this 2,000-foot ice dam, they flooded the valleys of western Montana. At its greatest extent, Glacial Lake Missoula stretched eastward a distance of some 200 miles, essentially creating an inland sea.

Periodically, the ice dam would fail. These failures were often catastrophic, resulting in a large flood of ice- and dirt-filled water that would rush down the Columbia River drainage, across northern Idaho and eastern and central Washington, through the Columbia River Gorge, back up into Oregon's Willamette Valley, and finally pour into the Pacific Ocean at the mouth of the Columbia River.

The glacial lake, at its maximum height and extent, contained more than 500 cubic miles of water. When Glacial Lake Missoula burst through the ice dam and exploded downstream, it did so at a rate 10 times the combined flow of all the rivers of the world. This towering mass of water and ice literally shook the ground as it thundered towards the Pacific Ocean, stripping away thick soils and cutting deep canyons in the underlying bedrock. With flood waters roaring across the landscape at speeds approaching 65 miles per hour, the lake would have drained in as little as 48 hours.

But the Cordilleran ice sheet continued moving south and blocking the Clark Fork River again and again, creating other Glacial Lake Missoulas. Over thousands of years, the lake filling, dam failure, and flooding were repeated dozens of times, leaving a lasting mark on the landscape of the Northwest. Many of the distinguishing features of the Ice Age Floods remain throughout the region today.

Modern history

In 1775, Bruno de Heceta became the first European to sight the mouth of the Columbia River, naming it either Bahía de la Asunción, or the San Rogue River. On May 11, 1792, Captain Robert Gray sailed into the Columbia River, becoming the first White to enter it. Gray had traveled to the Pacific Northwest to trade for fur in a privately owned vessel named Columbia Rediviva; he named the river after the ship. Gray spent nine days trading near the mouth of the Columbia, then left without having gone beyond 13 miles upstream. George Vancouver, commander of the British naval expedition that was exploring the region at the same time, soon learned that Gray claimed to have found a navigable river, and went to investigate for himself. In October 1792, Vancouver sent Lieutenant William Robert Broughton, his second-in-command, up the river. Broughton sailed up for some miles, then continued in small boats. He got as far as the Columbia River Gorge, about 100 miles upstream, sighting and naming Mount Hood. He also formally claimed the river, its watershed, and the nearby coast for Britain. Gray's discovery of the Columbia was used by the United States to support their claim to the Oregon Country, which was also claimed by Russia, Great Britain, Spain, and other nations.[7]

Lewis and Clark’s overland expedition explored the vast, unmapped lands west of the Missouri River. On the last stretch of their expedition in 1805 they traveled down the Columbia River to the Pacific Ocean.

David Thompson of the North West Company spent the winter of 1807–08 at Kootenae House near the source of the Columbia at present day Invermere, British Columbia. In 1811 he traveled down the Columbia to the Pacific Ocean, becoming the first European-American to travel the entire length of the river.

In 1825, on behalf of the Hudson's Bay Company, Dr. John McLoughlin established Fort Vancouver (currently Vancouver, Washington) on the banks of the Columbia as a fur trading headquarters in the region. The fort was by far the largest European settlement in the northwest of the time. Every year ships would come from London (via the Pacific) to drop off supplies and trade goods in exchange for the furs. For many settlers the fort became the last stop on the Oregon Trail to buy supplies and land before starting their homestead. Because of its access to the Columbia river, Fort Vancouver’s influence reached from Alaska to California and from the Rocky Mountains to the Hawaiian Islands.

By the turn of the 20th century, the difficulty of navigating the Columbia was seen as an impediment to the economic development of the Inland Empire region east of the Cascades.[8] The dredging and dam building that followed would permanently alter the river, disrupting its natural flow, but also providing electricity, irrigation, navigability, and other benefits to the region.

On February 13, 1980, $5,800 (in bundles of $20 bills) was found by a family on a picnic five miles northwest of Vancouver, Washington on the banks of the Columbia River. The money is believed by the FBI to be part of the 1971 Hijacker, D. B. Cooper’s ransom money.

On June 1, 2003, Christopher Swain of Portland, Oregon became the first person to swim the Columbia River's entire length[9].

Hydroelectric dams

| This river may have been shaped by God, or glaciers, or the remnants of the inland sea, or gravity or a combination of all, but the Army Corps of Engineers controls it now. The Columbia rises and falls, not by the dictates of tide or rainfall, but by a computer-activated, legally-arbitrated, federally-allocated schedule that changes only when significant litigation is concluded, or a United States Senator nears election time. In that sense, it is reliable. —Timothy Egan, in The Good Rain[10] |

The river's extreme elevation drop over a relatively short distance (2,700 feet in 1,232 miles (822 m in 1,982 km)) gives it tremendous potential for hydroelectricity generation. It was estimated in the 1960s – 70s that the Columbia represented 1/5 of the total hydroelectric capacity on Earth (although these estimates may no longer be accurate.) The Columbia drops 2.16 feet per mile (0.41 meters per kilometer), as compared with the Mississippi which drops less than 0.66 feet per mile (0.13 meters per kilometer).

Today, the mainstream of the Columbia River has 14 dams (three in Canada, 11 in the United States.) Four mainstem dams and four lower Snake River dams have locks to allow ship and barge passage. Numerous Columbia River tributaries have dams for hydroelectric and/or irrigation purposes. While hydroelectricity accounts for only 6.5% of energy in the United States, the Columbia and its tributaries provide approximately 60% of the hydroelectric power on the west coast.[11] The largest of the 150 hydroelectric projects, the Grand Coulee Dam and the Chief Joseph Dam, are also the largest in the United States; the Grand Coulee is the third largest in the world.

The dams also make it possible for ships to navigate the river, and provide irrigation. The dams in the United States are owned by the Federal Government (Army Corps of Engineers or Bureau of Reclamation), Public Utility Districts, and private power companies.

Grand Coulee Dam provides water for the Columbia Basin Project, one of the most extensive irrigation projects in the western United States. The project provides water to over 500,000 acres (2,000 km²) of fertile but arid lands in central Washington State. Water from the project has transformed the region from a wasteland barely able to produce subsistence levels of dry-land wheat crops to a major agricultural center. Important crops include apples, potatoes, alfalfa, wheat, corn (maize), barley, hops, beans, and sugar beets.

Although the dams provide benefits like clean, renewable energy, they drastically alter the landscape and ecosystem of the river. At one time the Columbia was one of the top salmon-producing river systems in the world. Previously active fishing sites, like Celilo Falls(covered by the river when The Dalles Dam was built) in the eastern Columbia River Gorge, have exhibited a sharp decline in fishing along the Columbia in the last century. The presence of dams, coupled with over-fishing, has played a major role in the reduction of salmon populations. Fish ladders[12] have been installed at some dam sites to help the fish journey to spawning waters. Grand Coulee Dam has no fish ladders and completely blocks fish migration to the upper half of the Columbia River system. Downriver of Grand Coulee, each dam’s reservoir is closely regulated by the Bonneville Power Administration, U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and various Washington Public Utility Districts to ensure flow, flood control, and power generation objectives are met. Increasingly, hydro-power operations are required to meet standards under the U.S. Endangered Species Act and other agreements to manage operations to minimize impacts on salmon and other fish, and some conservation and fishing groups support removing four dams on the lower Snake River, the largest tributary of the Columbia.

Pollution

The Hanford Site (a facility of the federal government established to provide plutonium necessary for the development of nuclear weapons, situated in Benton County, along the Columbia River)

EPA studies and state monitoring programs have found significant levels of toxins in fish and the waters they inhabit within the basin. Accumulation of toxins in fish threatens the survival of fish species, and human consumption of these fish can lead to health problems. Many governments, communities and citizens have rallied to launch a long term and intense recovery effort to restore these remarkable fish.

Water quality is also an important factor in the survival of other wildlife and plants that grow in the Columbia River Basin. The states, Indian tribes, and federal government are all engaged in efforts to restore and improve the water, land, and air quality of the Columbia River Basin and have committed to work together to enhance and accomplish critical ecosystem restoration efforts. A number of important work efforts are currently underway, including Portland Harbor in the Lower Basin, Hanford in the Middle Basin and Lake Roosevelt in the Upper Basin.[13]

Culture

<left>

| Roll on, Columbia, roll on, roll on, Columbia, roll on Your power is turning our darkness to dawn Roll on, Columbia, roll on. —Roll on Columbia by Woody Guthrie, written under commission of the Bonneville Power Administration |

With the importance of the Columbia to the Pacific Northwest, it has made its way into the culture of the area and the nation. Celilo Falls, in particular, was an important economic and cultural hub of western North America for as long as 10,000 years.

Several Indian tribes have a historical and continuing presence on the Columbia River, most notably the Sinixt or Lakes people in Canada and in the U.S. the Colvile, Spokane, Yakama, Nez Perce, Umatilla, Warm Springs Tribes. In the upper Snake River and Salmon River basin the Shoshone Bannock Tribes are present. In the Lower Columbia River, the Cowlitz and Chinook Tribes are present, but these tribes are not federally recognized. The Yakama, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Warm Springs Tribes all have treaty fishing rights in the Columbia River and tributaries.

In the movies

- Bend of the River (with James Stewart), has a river boat scene filmed on the Columbia River in 1952.

- In 1967, the episode “Ride the Mountain” of the television series Lassie featured the Columbia River Gorge.

- The Grand Coulee Dam was used in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984; Harrison Ford).

- The exterior river boat scenes from the 1994 film Maverick with (Mel Gibson, Jodie Foster, and James Garner), were shot on the Columbia River, in the Columbia River Gorge, near the town of Hood River.

- The dock scene for Snow Falling on Cedars (1999; Ethan Hawke) was filmed on the river at Cathlamet, Wahkiakum County, Washington.

- The rock jetty Free Willy jumps over to gain his freedom is located on the Oregon side of the river in the Hammond Boat Basin.

- In the film Bandits, the cast makes a stop at the Crown Point Vista House, which overlooks the river.

Major tributaries

Tributaries of the Columbia River

| Tributary | Discharge* |

|---|---|

| Snake River | 56,900 (1611) |

| Willamette River | 35,660 (1010) |

| Kootenai River | 30,650 (867) |

| Pend Oreille River | 27,820 (788) |

| Cowlitz River | 9,200 (261) |

| Spokane River | 6,700 (190) |

| Deschutes River | 6,000 (170) |

| Lewis River | 4,800 (136) |

| Yakima River | 3,540 (100) |

| Wenatchee River | 3,220 (91) |

| Okanogan River | 3,050 (86) |

| Kettle River | 2,930 (83) |

| Sandy River | 2,260 (64) |

* Average discharge, cubic feet per second (cubic meters per second)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ http://www.columbiariverkeeper.org/intro.htm Columbia River Keeper, The River. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ↑ Largest Rivers in the United States, USGS; retrieved April 21, 2007. Maximum and minimum discharge data from Water Data Report WA-05-1, chapter Klickitat and White Salmon River Basins and the Columbia River from Kennewick to Bonneville Dam; retrieved April 20, 2007. Identical data in: Loy, Willam G. and Stuart Allan, Aileen R. Buckley, James E. Meecham (2001). Atlas of Oregon. University of Oregon Press, 164-165. ISBN 0-87114-102-7.

- ↑ Google Earth coordinates for Columbia Lake. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ↑ Google Earth elevation for Columbia Lake. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ↑ USGS; Geographic Names Information System entry for Columbia River; retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ↑ Loy, Willam G. and Stuart Allan, Aileen R. Buckley, James E. Meecham (2001). Atlas of Oregon. University of Oregon Press, 24. ISBN 0-87114-102-7.

- ↑ Jacobs, Melvin C. (1938). Winning Oregon: A Study of An Expansionist Movement. The Caxton Printers, Ltd.. 77.

- ↑ Reeder, Lee B., "Open the Columbia to the sea", Pendleton Daily Tribune, E. P. Dodd, 1902. Retrieved 2007-05-13.

- ↑ http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1141/is_35_39/ai_106475689

- ↑ Egan, Timothy (1990). The Good Rain. Knopf.

- ↑ Energy Information Administration, "Electric Power Annual," http://www.eia.doe.gov/cneaf/electricity/epa/epa_sum.html; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, "Federal Columbia River Power System," brochure (2003), p. 1.

- ↑ http://www.fpc.org/

- ↑ EPA report on the Columbia

See also

- List of crossings of the Columbia River

- Columbia River Highway

- Columbia River Gorge

- Columbia Bar

- Tributaries of the Columbia River

- Empire Builder, an Amtrak rail line following much of the river from Portland to Spokane

- Cities on the Columbia River

- Hydroelectric dams on the Columbia River

- Cascades Rapids

- List of Washington rivers

- List of Oregon rivers

- List of British Columbia rivers

- Grays Point (Washington)

- Columbia River Treaty

- Bateman Island

Sources and Further Reading

- Lashnits, Tom. 2004. Columbia River. Rivers in American life and times. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers. ISBN 0791077284 and ISBN 9780791077283

- Jackson, Tom. 2004. The Columbia River. Rivers of North America. Milwaukee, Wis: Gareth Stevens Pub. ISBN 0836837541 and ISBN 9780836837544

- Dietrich, William. 1995. Northwest passage: the great Columbia River. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 067179650X and ISBN 9780671796501

- Lewis, Meriwether, William Clark, Nicholas Biddle, and Paul Allen. 1966. The Expedition of Lewis and Clark. March of America facsimile series, no. 56. Ann Arbor [Mich.]: University Microfilms.

External links

- Columbia River Basin. United States Environmental Protection Agency. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Bibliography on Water Resources and International Law. Peace Palace Libray. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Historic Columbia River Highway. Historic Columbia River Highway. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Virtual World Columbia River. National Geographic. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Columbia. BC Hydro. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Our Misson. Center for Columbia River History. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- Tollman and Canaris Photographs. University of Washington Libraries Digital Collections. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

- The Columbia River. Columbia River Fishing Guides. Retrieved June 15, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.