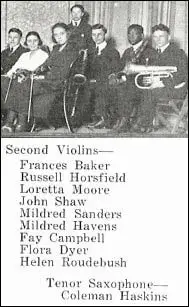

Coleman Hawkins

Coleman Randolph Hawkins (November 21, 1904 – May 19, 1969), nicknamed "Bean" or simply "Hawk," is considered the father of the tenor saxophone and more generally the father of all saxophone players.

Hawkins is one of the very few whose stature as a jazz soloist can be compared to that of Louis Armstrong or Charlie Parker. At the same time, the seriousness of his musicianship puts him at par with Duke Ellington, though he never was much of a composer himself. For his decisive contribution to the development of jazz as a genuine art form he has rightly been called a “true legend of twentieth century music.” While he never had Armstrong’s popular appeal, he soon acquired the status of an elder statesman among his peers.

The “invention” of the saxophone

Coleman Hawkins has been called the real inventor of the saxophone, because he elevated the instrument created by Adolphe Sax from the status of a marching band curiosity to that of the quintessential jazz instrument. Once liberated from its primitive, “slap-tongue” use, where players would produce a funny, slapping sound accompanying each note, the saxophone proved to be particularly well-suited to express the new jazz idiom. If it did not have the thunderous, conquering sound of the trumpet, with which Louis Armstrong and his predecessors opened the scene, its flexibility was second to none, combining expressive power with versatility. And when played by genuine artists, it could be as noble as any other instrument.

Hawkins opened the way for all saxophone players, be it tenor, alto, or baritone. An exception is Sidney Bechet whose soprano saxophone playing was already fully matured in 1923, but the soprano, to which he increasingly switched from the clarinet, was a different instrument altogether.

Biography

Early years

Hawkins was born in Saint Joseph, Missouri, in 1904. Some out-of-date sources say 1901, but there is no evidence to prove such an early date. He was named Coleman after his mother Cordelia's maiden name.

He attended high school in Chicago, then in Topeka, Kansas, at Topeka High School. He later stated that he studied harmony and composition for two years at Washburn College in Topeka while still attending THS. In his youth, he played piano and cello, and started playing saxophone at the age of nine; by the age of fourteen, he was playing around eastern Kansas.

At the age of 16, in 1921, Hawkins joined Mamie Smith's Jazz Hounds, with whom he toured through 1923, at which time he settled in New York City.

The Henderson years

Hawkins then joined Fletcher Henderson's Orchestra, with whom he played through 1934, occasionally doubling on clarinet and bass saxophone. Hawkins joined the band during the brief but decisive tenure of Louis Armstrong, whose hot trumpet totally revolutionized the band. Hawkins’ style was not directly influenced by Armstrong (their instruments were different and so were their temperaments), but Hawkins’ transformation, which matched that of the band as a whole, is certainly to be credited to Armstrong, his senior by several years. When he first joined Henderson, Hawk’s tenor sounded much like a quacking duck, as did all other saxophone players in the early 20s. Within a very short time, the jagged melody lines of his playing changed into a powerful staccato of overwhelming intensity that increasingly came to challenge the supremacy of the other horns. Hawkins became the main asset of a band that was filled with stars.

Europe

In 1934, Hawkins suddenly quit Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra and left for Europe, where he spent then next five years. In spite of the opportunities and the star status it had given him, the Henderson band was on the decline and Hawkins had begun to feel narrowed in there. During the mid to late 1930s, Hawkins toured Europe as a soloist, playing with Jack Hylton and other European bands that were far interior to those of the musical landscape he had known. Occasionally, his playing was affected by the lack of stimulating competition. But Hawkins also had the opportunity to play with first-class artists like Django Reinhardt and Stephane Grapelli, as well as scores of visiting American jazzmen like himself. Even when playing with inferior local bands, he would often produce remarkable solos ("Strange Fact," "Smiles," Holland, 1937).

The stay in Europe had another beneficial impact on Hawkins, as it did on other African-American musicians of that time. At home, they remained the object of racial discrimination whatever their status in the world of music. In Europe, they were not only accepted but enthusiastically welcomed and almost treated like royalty by local jazz fans and aspiring musicians. Hawkins and his colleagues also had the opportunity to get to know various aspect of European cultural life. Hawkins testified to this by entitling his groundbreaking 1948 unaccompanied solo, “Picasso.”

The European period came to an end with the outbreak of World War II, when Hawkins returned to the United States. In 1939, he recorded a seminal jazz solo on the pop standard "Body and Soul," a landmark equivalent to Armstrong's "West End Blues," that reestablished his standing after several years of absence.

The 1940s

The next decade was both one of fulfillment and one of transition. With his style fully matured and free from any affiliation to a particular band, Hawkins made a considerable number of recordings in a great variety of settings, both in studio and in concert. Hawkins briefly established a big band that proved commercially unsuccessful. He then mostly worked in a small combo setting (3 to 8 musicians), alongside other stars of classic jazz, such as Earl “Fatha” Hines and Teddy Wilson on piano, “Big Sid” Catlett and “Cozy” Cole on drums, Benny Carter on alto saxophone, and Vic Dickenson and Trummy Young on trombone—to name but a few. He developed a particularly close and lasting working relationship with trumpet great Roy Eldridge, himself a link between the world of swing and that of bebop. These recordings testify to Hawkins’ incredible creativity and to his improvisational skills—especially when several takes of the same piece recorded on the same day have been preserved: Each represents a unique masterpiece based on the same mold (Coleman Hawkins: The Alterative Takes, vol. 1-3, Neatwork, 2001).

But the 40s were also the time when bop emerged towards the end of World War II, ushering in a more serious, but also more tormented style, that would lead to a partial divorce between jazz music and show business. Eventually, it would deprive jazz from the large public appeal it had enjoyed during the swing era. But it also established it as serious music, not just popular entertainment.

Unlike other jazz greats of the swing era like Benny Goodman and Django Reinhardt, whose efforts at adapting to the new idiom were sometimes painful to hear, Hawkins was immediately at ease with the new developments. With the exception of Duke Ellington (and perhaps Mary Lou Williams), no other jazz musician has been able to remain creative from the early days of jazz until the advent of atonal music.

Coleman Hawkins led a combo at Kelly's Stables on Manhattan's famed 52nd Street, using Thelonious Monk, Oscar Pettiford, Miles Davis, and Max Roach as sidemen. He was leader on what is considered the first ever bebop recording session with Dizzy Gillespie and Don Byas in 1944. Later, he toured with Howard McGhee and recorded with J.J. Johnson, Fats Navarro, Milt Jackson, and most emerging giants. He also abundantly toured with Jazz at the Philharmonic and kept playing alongside the old (Louis Armstrong) and the new (Charlie Parker).

Late period

After 1948, Hawkins divided his time between New York and Europe, making numerous freelance recordings, including with Duke Ellington in 1962. In the 1960s, he appeared regularly at the Village Vanguard in Manhattan. Hawkins was always inventive and seeking new challenges. Until late in his career, he continued to record with many bebop performers whom he had directly influenced, including Sonny Rollins, who considered him his main influence, and such adventurous musicians as John Coltrane. He also kept performing with more traditional musicians, such as Henry "Red" Allen and Roy Eldridge, with whom he appeared at the 1957 Newport Jazz Festival.

The younger musicians who had been given their first chance by Hawkins and were now the stars of the day often reciprocated by inviting him to their sessions. Beyond that intent to reciprocate, together they produced genuinely great music. Almost surprisingly, Hawkins’ life nevertheless ended on a somewhat tragic note. After surviving numbers of challenges and making repeated comebacks (not that he had ever really disappeared), he did become somewhat disillusioned with the evolving situation of the recording industry. For this and personal reasons, his life took a downward turn in the late 60s and he practically allowed himself to die.

As his family life had fallen apart, the solitary Hawkins began to drink heavily and practically stopped eating. He also stopped recording (his last recording was in late 1966). Towards the end of his life, when appearing in concerts, he seemed as if leaning on his instrument for support but could nevertheless play brilliantly once he started (personal testimony, Geneva, 1967). He died of pneumonia and liver disease in 1969, and is interred at the Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx next to Duke Ellington, Lionel Hampton, and other jazz greats. Coleman Hawkins was one of the first jazzmen to be inducted into the Jazz at the Lincoln Center’s Hall of Fame in 2004.

Style

Hawkins’ sound was always gorgeous and perhaps its primary recognizable characteristic. At the same time, his playing was very inventive and harmonically advanced for his time. He also played very fast successions of notes, but never without a reason. This aspect of his art reminds the listener of clarinetist Buster Bailey and piano virtuoso Art Tatum, two musicians he much admired.

When listening to the regular, fast succession of notes in Hawkins playing in the late 20s, one is easily reminded of Johann Sebastian Bach’s contrapuntal work, but placed in the dynamic context of Henderson’s “stomping” band. Hawkins’ solos would mostly come in the form of forceful interventions, as if he was clearing woods with an ax. In the early 30s, his playing would take on an increasingly brighter and at the same time fuller tone. The rare quality of the sound remained unchanged from the beginning, but now there no longer was a sense that something needed to be conquered. Instead, the majestic, imperial tone that would characterize Hawkins for the rest of his career had settled in. Whoever he would play with from then on, he would always appear as primus inter pares.

Hawkins is remarkable for having developed two strikingly different styles concurrently towards the end of the 1930s. He had a soft, rounded, smooth, and incredibly warm sound on slow ballads. On faster, swinging tunes his tone was vibrant, intense and fiery, more like the way he played in his early years, but with added majesty. Hawkins himself explained the difference by his choice of reeds depending on the occasion. Around 1957, another change of mouthpieces led to a somewhat harsher tone, often combined with slower motion, less notes, and a bluesy touch. In “Driva Man,” recorded with Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln in 1960, Hawkins’ statement is reminiscent of the roar of an old lion. This and various other recordings show that Hawk did not mellow with age, quite to the contrary. Depending on the occasion, however, he could revert to any of the former sounds. His beautiful collaboration with Ellington (1962) displays Hawkins’ classic tone and phrasing as well as anything he ever played before. It is only in the later years of his career that some of Hawkins’ studio recordings came dangerously close to easy listening music, which shows how narrow the gap can be between great music and mere entertainment—and how the lack of motivation due to life circumstances can make the difference.

It has been often emphasized that Hawkins played along “vertical” harmonic structures, rather than subtle, easy-flowing melodic lines like Lester Young. His mastery of complex harmonies allowed him to penetrate the world of modern jazz as easily, but in a different way from Young’s cool style.

Hawkins’ 1948, unaccompanied solo “Picasso” represents another landmark in his career and in jazz history. The improvisation is perfectly constructed and, though the saxophone alone tends to sound lonely, it easily fills the scene by itself. “'Picasso’ perhaps best represents Hawkins’ production as “serious music.” It is generally considered to be the first unaccompanied sax solo ever recorded, though Hawkins recorded the much lesser known “Hawk’s Variations I & II” earlier, in 1945. On occasion, Hawkins also experimented with other styles, including the Bossa Nova (Desafinado: Bossa Nova and Jazz Samba, 1962) and playing with strings, following the lead of Charlie Parker.

In essence, Hawkins’ style can be considered classic. No matter how hard he would swing in faster tunes, he never crossed the line to extravagance. Compared to tenor players like Eddie Lockjaw Davis and Illinois Jacquet, his playing always remained controlled in spite of its intensity.

Influence

Practically all subsequent tenor players, large and small, were influenced by Hawkins, with the notable exception of Lester Young. As Hawkins gladly admits, many have developed great sounds of their own, among them Ben Webster and Leon Chu Berry. Some like Don Byas and Lucky Thompson have primarily inherited Hawk’s complex melodic and harmonic structures. Others are more reminiscent of his tone. Among them, [Ike Quebec]] perhaps comes closest, but without displaying the same creativity. Sonny Rollins can rightfully claim to be the overall continuator of Hawkins’ style in the setting of Hard Bop, though he never wanted to compare himself to his role model. Even Free Jazz tenor Archie Shepp immediately evokes Hawkins by his powerful, large sound. And Hawkins’ influence can also be felt in the play of baritone saxophone player Harry Carney.

Needless to say, Hawkins also remained open to the influence of others, including the much younger musicians he associated with later in life. Directly or indirectly, the two tenor greats of modern jazz, Sonny Rollins and John Coltrane, have in particular left their mark on their master’s style without really altering its basic nature. Hawkins is also known to have listened chiefly to classical music during his off time, which certainly contributed to the maturity of his style.

Special significance

There is another way in which Hawkins is an artist of exceptional stature and an innovator: His overall attitude towards his role as a jazz musician. Though such an assessment is more difficult to make and maybe more questionable than that of his undeniable influence on other tenor players, it is worth a serious consideration. In The Birth of Bebop, Mark DeVeaux calls Hawkins the “first modernist.” Here is how Sonny Rollins, Hawkins’ former protégé, expressed his agreement with that judgment: “Mark DeVeaux was particularly prescient in pointing out that Coleman was really the guy who was out there, just playing a horn, that was it. Louis [Armstrong] was setting the pace, too; but Louis also sang and entertained. … The thing that impressed me most about Coleman was his great dignity. … So, to me, Coleman’s carriage, a black musician who displayed that kind of pride – and who had the accomplishments to back it up – that was a refutation of the stereotypical images of how black people were portrayed by the larger society.”

Rollins continues by pointing out how Hawkins’ slow ballads played a special role in this development: “His ballad mastery was part of how he changed the conception of the “hot” jazz player. He changed the minstrel image. … He showed that a black musician could depict all emotions with credibility, even a beautiful ballad that represents the peak of civilization.” (Ultimate Coleman Hawkins, 1998).

It may be somewhat unfair to other jazz musicians to single out Hawkins in this way, but it is undeniable that most jazz greats of the swing and earlier periods had been unable to escape, at least entirely, the image of an entertainer, if not a buffoon – regardless of their musical genius. Pianist Fats Waller is known to have suffered from being expected to act as a clown, even though he did it very well. Even the greatest big band leaders, including Count Basie and Duke Ellington also acted as entertainers and were expected to. White musicians were perhaps less under pressure to seek acceptance in this way, but drummer Gene Krupa and trumpeter Harry James among many others were accomplished showmen as well. Interestingly, at the time when Hawkins more and more began to acquire the image of a serious musician, Louis Armstrong’s career followed an exactly opposite direction that allowed him to become popular with an increasingly large audience. Louis’ choice to accompany his wonderful music with a willingness to amuse the public is obviously related to his incredible popular appeal later in life, though it is irrelevant to his greatness as an artist. On the other hand, Hawkins’ ability to play jazz as a “serious” music without robbing it of any of its exciting character deserves to be noted.

Discography

- Early days with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra: “Stampede” (1927), “Variety Stomp” (1927), “Honeysuckle Rose” (1932), “New King Porter Stomp” (1932), “Hocus Pocus” (1934). With the McKinney’s Cotton Pickers: “Plain Dirt” (1929). With trumpeter Henry Red Allen: “I Wish I Could Shimmy Like My Sister Kate” (1933). With the Chocolate Dandies (next to Benny Carter on alto saxophone): “Smack” (1940). “Body and Soul” (1939).

- Some landmarks of the mature period: “Picasso” (unaccompanied solo, Paris, 1948), “The Man I Love” (1943), “Under a Blanket of Blue” (1944), “The Father Cooperates” (1944), “Through for the Night” (1944), “Flying Hawk” (with a young Thelonius Monk on piano, 1944), “La Rosita” (with Ben Webster), 1957).

- A 10 CD Box entitled Past Perfect. Coleman Hawkins Portrait (2001) includes many of Hawkins’ best recordings of the 30s, 40s, and early 50s, along with a 40 page booklet.

- “Ultimate Coleman Hawkins” (1998) contains highlights from the 40s (small combos) compiled by Sonny Rollins.

- “Duke Ellington Meets Coleman Hawkins” (1962): Mood Indigo, Self-Portrait (of The Bean)

- “Sonny [Rollins] Meets Hawk” (1963): Just Friends, Summertime.

- “We Insist! Freedom Now Suite” (1960): Driva Man. With Max Roach and Abbey Lincoln.

Filmography

- “After Hours” (1961) B&W, 27 min. The minimal and forgettable storyline is a mere pretext for some wonderful music by Hawkins, Roy Eldridge, Cozy Cole, Milt Hinton, and Johnny Guarnieri.

- Stormy Weather, Andrew L. Stone (1943).

- Hawkins’ music has also been used in a number of mainline movies.

Quotations

- "As far as I'm concerned, I think Coleman Hawkins was the President first, right? As far as myself, I think I'm the second one." Tenorman Lester Young, who was called "Pres," 1959 interview with Jazz Review.

- “Coleman [Hawkins] really set the whole thing as we know it today in motion.” Tenor great Sonny Rollins, Interview reproduced in the liner notes of “The Ultimate Coleman Hawkins” (1998).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chilton, John. The Song Of The Hawk. The Life And Recordings Of Coleman Hawkins. The University Of Michigan Press, 1990.

- DeVeaux, Mark. The Birth of Bebop. A Social And Musical History. University of California Press, 1997.

- James, Burnett. Coleman Hawkins. Turnbridge Wells: Spellmount, 1984.

External links

- BookRags biography. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- The Red Hot Jazz Archive biography. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- Jazz for Beginners biography. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- Includes a discography. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- Jazzreview.com. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

- Harlem.org This sites includes the famous Harlem 1958 Jazz Portrait. Hawkins prominent status among his peers appears from his central position in this historical photo. Retrieved March 7, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.