Difference between revisions of "Codex" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Codex Argenteus.jpg|thumb|240px|right|First page of the [[Codex Argenteus]]]] | |

| − | + | A '''codex''' ([[Latin]] for ''block of wood'', ''[[book]]''; plural ''codices'') is a book in the format used for modern books, with separate pages normally bound together and given a cover. It was a Roman invention that replaced the [[scroll]], which was the first form of book in all [[Eurasian]] cultures. | |

| + | |||

| + | Although technically any modern [[paperback]] is a codex, the term is used only for [[manuscript]] (hand-written) books, produced from [[Late Antiquity]] through the [[Middle Ages]]. The scholarly study of [[manuscript]]s from the point of view of the [[bookmaking]] craft is called [[codicology]]. The study of ancient documents in general is called [[paleography]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[New World]] codices were written as late as the 16th century (see [[Maya codices]] and [[Aztec codices]]). Those written before the Spanish conquests seem all to have been single long sheets folded [[concertina]]-style, sometimes written on both sides of the local [[amatl]] paper. So, strictly speaking they are not in codex format, but they more consistently have "Codex" in their usual names than do other types of manuscript. | ||

| − | [[ | + | The codex was an improvement upon the [[scroll]], which it gradually replaced, first in the West, and much later in Asia. The codex in turn became the [[printing|printed]] [[book]], for which the term is not used. In [[China]] books were already printed but only on one side of the paper, and there were [[woodblock printing|intermediate]] stages, such as scrolls folded [[concertina]]-style and pasted together at the back.<ref>[http://idp.bl.uk/education/bookbinding/bookbinding.a4d International Dunhuang Project - Several intermediate Chinese bookbinding forms from the C10th].</ref> |

| − | |||

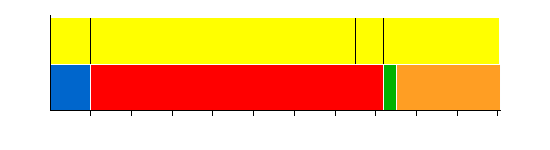

| − | + | <timeline> | |

| + | # définition de la taille de la frise | ||

| + | ImageSize = width:550 height:150 # taille totale de l'image : largeur, hauteur | ||

| + | PlotArea = width:450 height:95 left:50 bottom:40 # taille réelle de la frise au sein de l'image | ||

| + | DateFormat = yyyy # format des dates utilisées | ||

| + | Period = from:-200 till:2010 # laps de temps (de ... à ...) | ||

| + | TimeAxis = orientation:horizontal # orientation de la frise (verticale ou horizontale) | ||

| + | ScaleMajor = unit:year increment:200 start:0 # incrément temporel (majeur) | ||

| − | [[ | + | # définition des données de la frise |

| + | PlotData= | ||

| + | # définition de la première barre: 45 pixels de large, etc. | ||

| + | bar:Book color:yellow width:45 mark:(line,white) align:left fontsize:M | ||

| + | from: start till:2007 shift:(-15,30) | ||

| + | at:0 mark:(line, black) shift:(0,30) textcolor:black fontsize:8 text:[[Parchment]] | ||

| + | at:1300 mark:(line, black) shift:(-15,30) textcolor:black fontsize:8 text:[[Paper]] | ||

| + | at:1440 mark:(line, black) shift:(20,30) textcolor:black fontsize:8 text:[[Typography]] | ||

| + | bar:Evolution color: blue width:45 mark:(line,white) align:left fontsize:M | ||

| + | bar:Evolution color:blue from: start till: 0 shift:(-20,-60) textcolor:black text:[[Papyrus]] | ||

| + | bar:Evolution color:red from: 0 till: 1440 shift:(-15,-60) textcolor:black text:[[Codex]] | ||

| + | bar:Evolution color:green from: 1440 till: 1500 shift:(-65,-60) textcolor:black text:[[Incunabulum]] | ||

| + | bar:Evolution color:orange from: 1500 till: 2010 shift:(-20,-60)text:Modern book | ||

| + | </timeline> | ||

| − | |||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| − | The Romans used similar precursors made of reusable wax-covered tablets of wood for taking notes and other informal writings. The first recorded use of the codex for literary works dates from the late [[first century]] AD, when [[Martial]] experimented with the format. At that time the [[scroll (parchment)|scroll]] was the dominant medium for literary works and would remain dominant for secular works until the fourth century. [[Julius Caesar]], traveling in Gaul, found it useful to fold his scrolls [[concertina]]-style for quicker reference{{Fact|date=February 2007}}, as the Chinese also later did. As far back as the early [[2nd century]], there is evidence that the codex—usually of [[papyrus]]—was the preferred format among [[Christianity|Christians]]: in the library of the [[Villa of the Papyri]], [[Herculaneum]] (buried in AD 79), all the texts (Greek literature) are scrolls; in the [[Nag Hammadi]] "library, | + | The basic form of the codex was invented in [[Pergamon]] in the third century B.C.E. Rivalry between the Pergamene and Alexandrian libraries had resulted in the suspension of papyrus exports from Egypt. In response the Pergamenes developed [[parchment]] from sheepskin; because of the much greater expense it was necessary to write on both sides of the page. The Romans used similar precursors made of reusable wax-covered tablets of wood for taking notes and other informal writings. The first recorded Roman use of the codex for literary works dates from the late [[first century]] AD, when [[Martial]] experimented with the format. At that time the [[scroll (parchment)|scroll]] was the dominant medium for literary works and would remain dominant for secular works until the fourth century. [[Julius Caesar]], traveling in Gaul, found it useful to fold his scrolls [[concertina]]-style for quicker reference{{Fact|date=February 2007}}, as the Chinese also later did. As far back as the early [[2nd century]], there is evidence that the codex—usually of [[papyrus]]—was the preferred format among [[Christianity|Christians]]: in the library of the [[Villa of the Papyri]], [[Herculaneum]] (buried in AD 79), all the texts (Greek literature) are scrolls; in the [[Nag Hammadi]] "library", secreted about AD 390, all the texts (Gnostic Christian) are codices. The earliest surviving fragments from codices come from Egypt and are variously dated (always tentatively) towards the end of the 1st century or in the first half of the 2nd. This group includes the [[Rylands Library Papyrus P52]], containing part of St John's Gospel, and perhaps dating from between 125 and 160.<ref>Turner ''The Typology of the Early Codex'', U Penn 1977, and Roberts & Skeat ''The Birth of the Codex'' (Oxford University 1983). From Robert A Kraft (see link): "A fragment of a Latin parchment codex of an otherwise unknown historical text dating to about 100 C.E. was also found at Oxyrhynchus (POx 30; see Roberts & Skeat 28). Papyrus fragments of a "Treatise of the Empirical School" dated by its editor to the centuries 1-2 C.E. is also attested in the Berlin collection (inv. # 9015, Pack\2 # 2355) - Turner, Typology # 389, and Roberts & Skeat 71, call it a "medical manual.""</ref> |

| − | + | [[Image:KellsFol034rChiRhoMonogram.jpg|right|240px|thumb|The [[Labarum|Chi Rho]] Monogram from the [[Book of Kells]]]] | |

| + | [[Image:Kodeks IV NagHammadi.jpg|thumb|240px|right|The [[Nag Hammadi library]] is a collection of [[Early Christianity|early Christian]] [[Gnostic]] texts discovered near the [[Egypt|Egyptian]] town of [[Nag Hammadi]] in 1945.]] | ||

| + | [[Image:Codex sinaticus.jpg|thumb|240px|A portion of the ''[[Codex Sinaiticus]]'', containing [[Book of Esther|Esther]] 2:3-8.]] | ||

In [[Western culture#Foundations|Western culture]] the codex gradually replaced the scroll. From the fourth century, when the codex gained wide acceptance, to the [[Carolingian Renaissance]] in the eighth century, many works that were not converted from scroll to codex were lost to posterity. The codex was an improvement over the scroll in several ways. It could be opened flat at any page, allowing easier reading; the pages could be written on both [[recto]] and [[verso]]; and the codex, protected within its durable covers, was more compact and easier to transport. | In [[Western culture#Foundations|Western culture]] the codex gradually replaced the scroll. From the fourth century, when the codex gained wide acceptance, to the [[Carolingian Renaissance]] in the eighth century, many works that were not converted from scroll to codex were lost to posterity. The codex was an improvement over the scroll in several ways. It could be opened flat at any page, allowing easier reading; the pages could be written on both [[recto]] and [[verso]]; and the codex, protected within its durable covers, was more compact and easier to transport. | ||

| Line 25: | Line 49: | ||

In Asia, the scroll remained standard for far longer than in the West. The [[Jewish]] religion still retains the [[Torah]] scroll, at least for ceremonial use. | In Asia, the scroll remained standard for far longer than in the West. The [[Jewish]] religion still retains the [[Torah]] scroll, at least for ceremonial use. | ||

{{-}} | {{-}} | ||

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | == | + | <references/> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

| − | * | + | * Lists: |

| − | *[[ | + | :*[[List of codices]] |

| − | + | :*[[List of New Testament papyri]] | |

| − | + | :*[[List of New Testament uncials]] | |

| − | *[[List of New Testament papyri]] | ||

| − | *[[List of New Testament uncials | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * Specific traditions: | |

| − | + | :*[[Aztec codices]] | |

| + | :*[[Traditional Chinese bookbinding]] | ||

| + | :*[[Maya codices]] | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | *[http://www.kchanson.com/papyri.html K.C. Hanson, ''Catalogue of New Testament Papyri & Codices 2nd—10th Centuries''] |

| − | + | * David Diringer, The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental, Courier Dover Publications, New York 1982, ISBN 0486242439 | |

| + | * C.H. Roberts – T.C. Skeat, The Birth of the Codex, Oxford University Press, New York – Cambridge 1983. | ||

| + | * L.W. Hurtado, The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins, Cambridge 2006. | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | *[http://www.hss.ed.ac.uk/chb Centre for the History of the Book] | |

| − | + | *[http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/gopher/other/journals/kraftpub/Christianity/Canon The Codex and Canon Consciousness - Draft paper by Robert Kraft on the change from scroll to codex] | |

| − | *[http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/gopher/other/journals/kraftpub/Christianity/Canon | + | * [http://www.mathcs.duq.edu/~tobin/maya/ The Construction of the Codex In Classic- and Postclassic-Period Maya Civilization] Maya Codex and Paper Making |

| − | * [http://www.mathcs.duq.edu/~tobin/maya/ The Construction of the Codex In Classic- and Postclassic-Period Maya Civilization] | + | *[http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/scroll/scrollcodex.html Encyclopaedia Romana: "Scroll and codex"] |

| − | *[http://penelope.uchicago.edu/~grout/encyclopaedia_romana/scroll/scrollcodex.html "Scroll and codex"] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 01:29, 8 October 2008

A codex (Latin for block of wood, book; plural codices) is a book in the format used for modern books, with separate pages normally bound together and given a cover. It was a Roman invention that replaced the scroll, which was the first form of book in all Eurasian cultures.

Although technically any modern paperback is a codex, the term is used only for manuscript (hand-written) books, produced from Late Antiquity through the Middle Ages. The scholarly study of manuscripts from the point of view of the bookmaking craft is called codicology. The study of ancient documents in general is called paleography.

New World codices were written as late as the 16th century (see Maya codices and Aztec codices). Those written before the Spanish conquests seem all to have been single long sheets folded concertina-style, sometimes written on both sides of the local amatl paper. So, strictly speaking they are not in codex format, but they more consistently have "Codex" in their usual names than do other types of manuscript.

The codex was an improvement upon the scroll, which it gradually replaced, first in the West, and much later in Asia. The codex in turn became the printed book, for which the term is not used. In China books were already printed but only on one side of the paper, and there were intermediate stages, such as scrolls folded concertina-style and pasted together at the back.[1]

History

The basic form of the codex was invented in Pergamon in the third century B.C.E. Rivalry between the Pergamene and Alexandrian libraries had resulted in the suspension of papyrus exports from Egypt. In response the Pergamenes developed parchment from sheepskin; because of the much greater expense it was necessary to write on both sides of the page. The Romans used similar precursors made of reusable wax-covered tablets of wood for taking notes and other informal writings. The first recorded Roman use of the codex for literary works dates from the late first century AD, when Martial experimented with the format. At that time the scroll was the dominant medium for literary works and would remain dominant for secular works until the fourth century. Julius Caesar, traveling in Gaul, found it useful to fold his scrolls concertina-style for quicker reference[citation needed], as the Chinese also later did. As far back as the early 2nd century, there is evidence that the codex—usually of papyrus—was the preferred format among Christians: in the library of the Villa of the Papyri, Herculaneum (buried in AD 79), all the texts (Greek literature) are scrolls; in the Nag Hammadi "library", secreted about AD 390, all the texts (Gnostic Christian) are codices. The earliest surviving fragments from codices come from Egypt and are variously dated (always tentatively) towards the end of the 1st century or in the first half of the 2nd. This group includes the Rylands Library Papyrus P52, containing part of St John's Gospel, and perhaps dating from between 125 and 160.[2]

In Western culture the codex gradually replaced the scroll. From the fourth century, when the codex gained wide acceptance, to the Carolingian Renaissance in the eighth century, many works that were not converted from scroll to codex were lost to posterity. The codex was an improvement over the scroll in several ways. It could be opened flat at any page, allowing easier reading; the pages could be written on both recto and verso; and the codex, protected within its durable covers, was more compact and easier to transport.

The codex also made it easier to organize documents in a library because it had a stable spine on which the title of the book could be written. The spine could be used for the incipit, before the concept of a proper title was developed, during medieval times.

Although most early codices were made of papyrus, papyrus was fragile and supplies from Egypt, the only place where papyrus grew, became scanty; the more durable parchment and vellum gained favor, despite the cost.

The codices of pre-Columbian Mesoamerica had the same form as the European codex, but were instead made with long folded strips of either fig bark (amatl) or plant fibers, often with a layer of whitewash applied before writing.

In Asia, the scroll remained standard for far longer than in the West. The Jewish religion still retains the Torah scroll, at least for ceremonial use.

Notes

- ↑ International Dunhuang Project - Several intermediate Chinese bookbinding forms from the C10th.

- ↑ Turner The Typology of the Early Codex, U Penn 1977, and Roberts & Skeat The Birth of the Codex (Oxford University 1983). From Robert A Kraft (see link): "A fragment of a Latin parchment codex of an otherwise unknown historical text dating to about 100 C.E. was also found at Oxyrhynchus (POx 30; see Roberts & Skeat 28). Papyrus fragments of a "Treatise of the Empirical School" dated by its editor to the centuries 1-2 C.E. is also attested in the Berlin collection (inv. # 9015, Pack\2 # 2355) - Turner, Typology # 389, and Roberts & Skeat 71, call it a "medical manual.""

See also

- Lists:

- List of codices

- List of New Testament papyri

- List of New Testament uncials

- Specific traditions:

- Aztec codices

- Traditional Chinese bookbinding

- Maya codices

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- K.C. Hanson, Catalogue of New Testament Papyri & Codices 2nd—10th Centuries

- David Diringer, The Book Before Printing: Ancient, Medieval and Oriental, Courier Dover Publications, New York 1982, ISBN 0486242439

- C.H. Roberts – T.C. Skeat, The Birth of the Codex, Oxford University Press, New York – Cambridge 1983.

- L.W. Hurtado, The Earliest Christian Artifacts: Manuscripts and Christian Origins, Cambridge 2006.