Difference between revisions of "Cheyenne" - New World Encyclopedia

(Started) |

({{Contracted}}) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Claimed}}{{Started}} | + | {{Claimed}}{{Started}}{{Contracted}} |

[[category:Politics and social sciences]] | [[category:Politics and social sciences]] | ||

[[category:Anthropology]] | [[category:Anthropology]] | ||

Revision as of 14:11, 7 September 2007

| Cheyenne |

|---|

| Total population |

| 6,591 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (Oklahoma, Montana) |

| Languages |

| Cheyenne, English |

| Religions |

| Christianity, other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Arapaho and other Algonquian peoples |

The Cheyenne are a Native American nation of the Great Plains. The Cheyenne nation is composed of two united tribes, the Sotaeo'o [no definite translation] and the Tsitsistas, which translates to "Like Hearted People." The name Cheyenne itself derives from a Sioux word meaning 'Little Cree'.

During the pre-reservation era, they were allied with the Arapaho and Lakota (Sioux). They are one of the best known of the Plains tribes. The Cheyenne nation comprised ten bands, spread all over the Great Plains, from southern Colorado to the Black Hills in South Dakota. In the mid-1800s, the bands began to split, with bands choosing to remain near the Black Hills, while the other bands chose to remain near the Platte Rivers of central Colorado.

Currently the Northern Cheyenne live in southeast Montana on the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation . The Southern Cheyenne, along with the Southern Arapaho, live in central Oklahoma. Their combined population is approximately 20,000.

Language

The Cheyenne of Montana and Oklahoma speak the cheyenne language, with only a handful of vocabulary items different between the two locations (their alphabet only contains fourteen letters which can be combined to form words and phrases). The Cheyenne language is part of the larger Algonquian language group, and is one of the few Plains Algonquian languages to have developed tonal characteristics. The closest linguistic relatives of the Cheyenne language are Arapaho and Ojibwa (Chippewa).

Early history and culture

Nothing is absolutely known about the Cheyenne people prior to the 16th century.

The earliest known official record of the Cheyenne comes from the mid-1600s, when a group of Cheyenne visited Fort Crevecoeur, near present-day Chicago. During the 1600 and 1700s, the Cheyenne moved from the Great Lakes region to present day Minnesota and North Dakota and established villages. The most prominent of these ancient villages is Biesterfeldt Village, in eastern North Dakota along the Sheyenne River. The Cheyenne also came into contact with the neighboring Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara nations and adopted many of their cultural characteristics. In 1804, the Lewis and Clark visited a Cheyenne village in North Dakota. Pressure from migrating Lakota and Ojibwa nations was forcing the Cheyenne west. By the mid 1800s, the Cheyenne had largely abandoned their sedentary, agricultural and pottery traditions and fully adopted the classic nomadic Plains culture. Tipis replaced earth lodges, and the diet switched from fish and agricultural produce to mainly bison and wild fruits and vegetables. During this time, the Cheyenne also moved into Wyoming, Colorado and South Dakota.

The traditional Cheyenne government system is a politically unified North American indigenous nation. Most other nations were divided into politically autonomous bands, whereas the the Cheyenne bands were politically unified. The central traditional government system of the Cheyenne was the "Council of Forty-four." The name denotes the number of seated chiefs on the council. Each band had 4 seated chief delegates; the remaining 4 chiefs were the principal advisors of the other delegates. This system also regulated the many societies that developed for planning warfare, enforcing rules, and conducting ceremonies. This governing system was developed by the time the Cheyenne reached the Great Plains.

There is a controversy among anthropologists about Cheyenne society organization. When the Cheyenne were fully adapted to the classic Plains culture, they had a bi-lateral band kinship system. However, some anthropologists note that the Cheyenne had a matrilineal band system. Studies into whether the Cheyenne ever developed a matrilineal clan system are inconclusive.

19th century and Indian Wars

In 1851, the first Cheyenne 'territory' was established in northern Colorado. The Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851 granted this territory. Today this former territory includes the cities of Fort Collins, Denver and Colorado Springs.

Starting in the late 1850s and accelerating in 1859 with the Colorado Gold Rush, European settlers moved into the lands reserved for the Cheyenne and other Plains Indians.. The influx eventually led to open warfare in the 1864 Colorado War, primarily between the Kiowa with the Cheyenne largely uninvolved, but caught in the middle of the conflict.

In November, 1864, a Cheyenne encampment under Chief Black Kettle, flying a flag of truce and indicating its allegiance to the authority of the national government, was attacked by the Colorado Militia. The battle, known as the Sand Creek Massacre resulted in the death of between 150 and 200 Cheyenne, mostly unarmed noncombatants.

Four years later, on November 27, 1868, the same Cheyenne band was attacked at the Battle of Washita River. The encampment under Chief Black Kettle was located within the defined reservation and thus complying with the government's orders, but some of its members were linked both pre and post battle to the ongoing raiding into Kansas by bands operating out of the Indian Territory. Over 100 Cheyenne were killed, mostly women and children.

There are conflicting claims as to whether the band was "hostile" or "friendly." Chief Black Kettle, head of the band, is generally accepted as not being part of the war party within the Plains tribes, but he did not command absolute authority over the members of his band. Consequently, when younger members of the band participated in the raiding, the band was implicated.

The Northern Cheyenne also participated in the Battle of the Little Bighorn, which took place on June 25, 1876. The Cheyenne, along with the Lakota and a small band of Arapaho, annihilated George Armstrong Custer and much of his 7th Cavalry contingent of Army soldiers. It is estimated that population of the encampment of the Cheyenne, Lakota and Arapaho along the Little Bighorn River was approximately 10,000, which would make it one of the largest gathering of Native Americans in North America in pre-reservation times. News of the event had traveled across the United States, and reached Washington DC just as the United States was celebrating its Centennial. This caused much anger towards the Cheyenne and Lakota.

Northern Cheyenne exodus

Following the Battle of the Little Bighorn attempts by the U.S. Army to capture the Cheyenne intensified. A group of 972 Cheyenne were escorted to Indian Territory in Oklahoma in 1877. The government intended to re-unite both the Northern and Southern Cheyenne into one nation. There the conditions were dire; the Northern Cheyenne were not used to the climate and soon many became ill with malaria. In addition, the food rations were insufficient and of poor quality. In 1878, the two principal Chiefs, Little Wolf and Morning Star (Dull Knife) pressed for the release of the Cheyenne so they could travel back north.

That same year a group of 353 Cheyenne left Indian Territory to travel back north. This group was led by Chiefs Little Wolf and Morning Star. The Army and other civilian volunteers were in hot pursuit of the Cheyenne as they traveled north. It is estimated that a total of 13,000 Army soldiers and volunteers were sent to pursue the Cheyenne over the whole course of their journey north. There were several skirmishes that occurred, and the two head chiefs were unable to keep some of their young warriors from attacking small white settlements along the way.

After crossing into Nebraska, the group split into two. One half was led by Little Wolf, and the other by Morning Star. Little Wolf and his band made it back to Montana. Morning Star and his band were captured and escorted to Fort Robinson, Nebraska. There Morning Star and his band were sequestered. They were ordered to return to Oklahoma but they refused. Conditions at the fort grew tense through the end of 1878 and soon the Cheyenne were confined to barracks with no food, water or heat. Finally there was an attempt to escape late at night on January 9, 1879. Much of the group was gunned down as they ran away from the fort, and others were discovered near the fort during the following days and ordered to surrender but most of the escapees chose to fight because they would rather be killed than taken back into custody. It is estimated that only 50 survived the breakout, including Morning Star (Dull Knife). Several of the escapees later had to stand trial for the murders which had been committed in Kansas. The remains of those killed were repatriated in 1994.

Northern Cheyenne return

The Cheyenne traveled to Fort Keogh (present day Miles City, Montana) and settled near the fort. Many of the Cheyenne worked with the army as scouts. The Cheyenne scouts were pivotal in helping the Army find Chief Joseph and his band of Nez Percé in northern Montana. Fort Keogh became the staging and gathering point for the Northern Cheyenne. Many families began to migrate south to the Tongue River watershed area and established homesteads. Seeing a need for a reservation, the United States government established, by executive order, a reservation in 1884. The Cheyenne would finally have a permanent home in the north. The reservation was expanded in 1890, the current western border is the Crow Indian Reservation, and the eastern border is the Togue River. The Cheyenne, along with the Lakota and Apache nations, were the last nations to be subdued and placed on reservations (the Seminole tribe of Florida was never subdued.).

Through determination and sacrifice, the Northern Cheyenne had earned their right to remain in the north near the Black Hills. The Cheyenne also had managed to retain their culture, religion and language intact. Today, the Northern Cheyenne Nation is one of the few American Indian nations to have control over the majority of its land base, currently at 98%.

Over the past four hundred years, the Cheyenne have gone through four stages of culture. First they lived in the Eastern Woodlands and were a sedentary and agricultural people, planting corn, and beans. Next they lived in present day Minnesota and South Dakota and continued their farming tradition and also started hunting the bison of the Great Plains. During the third stage the Cheyenne abandoned their sedentary, farming lifestyle and became a full-fledged Plains horse culture tribe. The fourth stage is the reservation phase.

Council of Forty-Four

The Council of Forty-Four was one of the two central institutions of traditional Cheyenne Indian tribal governance, the other being the military societies such as the Dog Soldiers. The influence of the Council of Forty-Four waned in the face of internal conflict among the Cheyenne about Cheyenne policy toward encroaching white settlers on the Great Plains, and was dealt a severe blow by the Sand Creek Massacre.

The Council of Forty-Four was the council of chiefs, comprising four chiefs from each of the ten Cheyenne bands plus four principal[1] or "Old Man" chiefs who had previously served on the council with distinction.[2] Council chiefs were generally older men who commanded wide respect; they were responsible for day-to-day matters affecting the tribe[2] as well as the maintenance of peace both within and without the tribe by force of their moral authority.[3] While chiefs of individual bands held primary responsibility for decisions affecting their own bands, matters which involved the entire tribe such as treaties and alliances required discussions by the entire Council of Forty-Four.[4] Chiefs were not chosen by vote, but rather by the Council of Forty-four, whose members named their own successors, with chiefs generally chosen for periods of ten years at councils held every four years. Many chiefs were chosen from among the ranks of the military societies, but were required to give up their society memberships upon selection.[1]

Military societies

While chiefs were responsible for overall governance of individual bands and the tribe as a whole, the chiefs or headmen of military societies were in charge of maintaining discipline within the tribe, overseeing tribal hunts and ceremonies, and providing military leadership.[2] Council chiefs selected which of the six military societies would assume these duties; after a period of time on-duty, the chiefs would select a different society to take up the duties.[5]

The six military societies included:

- Dog Men (Hotamitaneo), called Dog Soldiers by the whites

- Bowstring Men (Himatanohis) or Wolf Warriors (Konianutqio); among the Southern Cheyenne only.

- Foolish or Crazy Dogs (Hotamimasaw); similar to the Bowstrings, but found only among the Northern Cheyenne.

- Crooked Lance Society (Himoiyoqis) or Bone Scraper Society. This was the society of the famous warrior Roman Nose, and also of the mixed-blood Cheyenne George Bent.

- Red Shields (Mahohivas) or Bull Soldiers

- Kit Fox Men (Woksihitaneo)[6]

Deterioration of traditional tribal government

Beginning in the 1830s, the Dog Soldiers had evolved from the Cheyenne military society of the same name into a separate, composite band of Cheyenne and Lakota warriors that took as its territory the headwaters country of the Republican and Smoky Hill rivers in southern Nebraska, northern Kansas, and the northeast of Colorado Territory. By the 1860s, as conflict between Indians and encroaching whites intensified, the influence wielded by the militaristic Dog Soldiers, together with that of the military societies within other Cheyenne bands, had become a significant counter to the influence of the traditional Council of Forty-Four chiefs, who were more likely to favor peace with the whites.[7]

The Sand Creek Massacre of November 29, 1864, besides causing a heavy loss of life and material possessions by the Cheyenne and Arapaho bands present at Sand Creek, also devastated the Cheyenne's traditional government, due to the deaths at Sand Creek of eight of 44 members of the Council of Forty-Four, including White Antelope, One Eye, Yellow Wolf, Big Man, Bear Man, War Bonnet, Spotted Crow, and Bear Robe, as well as headmen of some of the Cheyenne's military societies.[8] Among the chiefs killed were most of those who had advocated peace with white settlers and the U.S. government.[9] The effect of this on Cheyenne society was to exacerbate the social and political rift between the traditional council chiefs and their followers on the one hand and the Dog Soldiers on the other.[7] To the Dog Soldiers, the Sand Creek Massacre illustrated the folly of the peace chiefs' policy of accommodating the whites through the signing of treaties such as the first Treaty of Fort Laramie and the Treaty of Fort Wise[10] and vindicated the Dog Soldiers' own militant posture towards the whites.[7] The traditional Cheyenne clan system, upon which the system of choosing chiefs for the Council of Forty-Four depended, was dealt a fatal blow by the events at Sand Creek.[11] The morale authority of traditional Council chiefs to moderate the behavior of the tribe's young men and to treat with whites was severely hampered by these events as well as the ascendancy of the Dog Soldiers' militant policies.

Dog Soldiers

The Dog Soldiers or Dog Men (Cheyenne Hotamitaneo) was one of six military societies of the Cheyenne Indians. Beginning in the late 1830s, this society evolved into a separate, militaristic band which played a dominant role in Cheyenne resistance to American expansion in Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, and Wyoming, often in opposition to the policies of peace chiefs such as Black Kettle. Today the Dog Soldiers society is making a comeback in such areas as the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana and the Cheyenne-Arapaho Indian Reservation in Oklahoma.

Cheyenne tribal governance

Military societies, also called soldier societies, were one of two central institutions of traditional Cheyenne tribal governance, the other being the Council of Forty-Four.[2]

Council of Forty-Four

The Council of Forty-Four was the council of chiefs, comprising four chiefs from each of the ten Cheyenne bands plus four principal[1] or "Old Man" chiefs who had previously served on the council with distinction.[2] Council chiefs were generally older men who commanded wide respect; they were responsible for day-to-day matters affecting the tribe[2] as well as the maintenance of peace both within and without the tribe by force of their moral authority.[3] While chiefs of individual bands held primary responsibility for decisions affecting their own bands, matters which involved the entire tribe such as treaties and alliances required the discussions by the entire Council of Forty-Four.[4] Chiefs were not chosen by vote, but rather by the Council of Forty-four, which named its own successors, with chiefs generally chosen for periods of ten years at councils held every four years. Many chiefs were chosen from among the ranks of the military societies, but were required to give up their society memberships upon selection.[1]

Military societies

While chiefs were responsible for overall governance of individual bands and the tribe as a whole, the chiefs or headmen of military societies were in charge of maintaining discipline within the tribe, overseeing tribal hunts and ceremonies, and providing military leadership.[2] Chiefs selected which of the six military societies would assume these duties; after a period of time on-duty, the chiefs would select a different society to take up the duties.[5]

The six military societies included:

- Dog Men (Hotamitaneo), called Dog Soldiers by the whites

- Bowstring Men (Himatanohis) or Wolf Warriors (Konianutqio); among the Southern Cheyenne only.

- Foolish or Crazy Dogs (Hotamimasaw); similar to the Bowstrings, but found only among the Northern Cheyenne.

- Crooked Lance Society (Himoiyoqis) or Bone Scraper Society. This was the society of the famous warrior Roman Nose, and also of the mixed-blood Cheyenne George Bent.

- Red Shields (Mahohivas) or Bull Soldiers

- Kit Fox Men (Woksihitaneo)[6]

The Dog Soldiers

Dog Soldiers were noted as both highly aggressive and effective combatants. One tradition states that in battle they would "pin" themselves to a "chosen" piece of ground, through an unusually long breech-clout "rear-apron," by use of one of three "Sacred Arrows" they would constantly carry into battle.

Emergence as a separate band

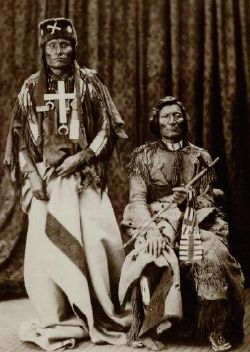

Porcupine Bear

Prior to the peace council held at Bent's Fort in 1840, there was enmity between the Cheyennes and Arapaho on one side and the Comanches, Kiowas, and Plains Apaches on the other. In 1837, while raiding the Kiowa horse herds along the North Fork of the Red River, a party of 48 Cheyenne Bowstring Men were discovered and killed by the Kiowas and Comanches.[12] Porcupine Bear, chief of the Dog Soldiers, took up the war pipe of the Cheyenne and proceeded to carry it to the various Cheyenne and Arapaho camps in order to drum up support for revenge against the Kiowas. He reached a Northern Cheyenne camp along the South Platte River just after it had traded for liquor from American Fur Company men at Fort Laramie. Porcupine Bear joined in the drinking and soon was sitting alone in a corner, very drunk, singing Dog Soldier war songs to himself. Two of his cousins, Little Creek and Around, became caught up in a drunken fight. Little Creek got on top of Around and held up a knife, ready to stab Around; at that point, Porcupine Bear, aroused by Around's calls for help, leapt up in a rage, tore the knife away from Little Creek, and stabbed him with it several times. He then compelled Around to finish Little Creek off.[13][14]

By the rules governing military societies, a man who had murdered or even accidentally killed another tribe member was prohibited from joining a society, and a society member who committed such a crime was expelled and outlawed.[15] Therefore Porcupine Bear for his act of murder was expelled from the Dog Soldiers and, along with all his relatives, was made to camp apart from the rest of the tribe.[15][16] The Dog Soldiers were also disgraced by Porcupine Bear's act. They were deprived of their leadership in bringing war against the Kiowas. Yellow Wolf reformed the Bowstring Society, which had been nearly annihilated in the fight with the Kiowas, and the task of leading the effort against the Kiowas was entrusted to them.[17][16] Though outlawed by the main body of the Cheyenne tribe, Porcupine Bear led the Dog Soldiers as participants into battle against the Kiowas and Comanches at Wolf Creek; they were reportedly the first to strike the enemy.[16][18] Due to their outlaw status, however, they were not accorded honors.[16]

Dog Soldier band

The outlawing of Porcupine Bear, his relatives, and his followers led to the transformation of the Dog Soldiers from a military society into a separate division of the tribe.[16][19] In the wake of a cholera epidemic in 1849 which greatly reduced the Masikota band of Cheyennes,[20] the remaining Masikota joined the Dog Soldiers;[19] thereafter when the Cheyenne bands camped together, the Dog Soldier band took the position in the camp circle formerly occupied by the Masikota.[21] Prominent or ambitious warriors from other bands also gradually joined the Dog Soldier band, and over time as the Dog Soldiers took a prominent leadership role in the wars against the whites, the rest of the tribe began to regard them no longer as outlaws but with great respect.[19]

The Dog Soldiers contributed to the breakdown of the traditional clan system of the Cheyennes. Customarily when a man married, he moved to the camp of his wife's band. The Dog Soldiers dropped this custom, instead bringing their wives to their own camp.[19] Other contributors to the breakdown of the clan system were the 1849 cholera epidemic, which killed perhaps half the Southern Cheyenne population,[22] particularly devastating the Masikota band and nearly wiping out the Oktoguna;[20] and the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, which especially decimated the Wutapai (Black Kettle's band), killed perhaps half of the Hevhaitaniu under Yellow Wolf and Big Man and the Oivimana under War Bonnet, and causing heavy losses also to the Hisiometanio (Ridge Men) under White Antelope. The Dog Soldiers and the Masikota, who had by that time joined the Dog Soldiers, were not present at Sand Creek.[11]

The Dog Soldiers band took as its territory the headwaters country of the Republican and Smoky Hill rivers in southern Nebraska, northern Kansas, and the northeast of Colorado Territory.[21][7][23]They were friends to the Lakota and Brulé Lakotas, who also frequented that area, and often intermarried with the Lakota. Many Dog Soldiers were half-Lakota, including the Dog Soldier chief Tall Bull.[21]

Due to an increasing polarity between the Dog Soldiers and the council chiefs with respect to policy towards the whites, the Dog Soldiers were somewhat divorced from the other Southern Cheyenne bands.[23][10] They effectively became a third division of the Cheyenne people, between the Northern Cheyenne who ranged north of the Platte River and the Southern Cheyennes who occupied the area along the Arkansas River.[2][23] A strong band numbering perhaps 100 lodges, the Dog Soldiers had a generally antagonistic attitude towards the encroaching whites.[23] By the 1860s, as conflict between Indians and whites intensified, the influence wielded by the militaristic Dog Soldiers, together with that of the military societies within other Cheyenne bands, had become a significant counter to the influence of the traditional Council of Forty-Four chiefs, who were more likely to favor peace with the whites.[7]

Indian wars

In the late 1860s, the Dog Soldiers were crucial in Cheyenne resistance to American expansion. Dog Soldiers refused to sign treaties that limited their hunting grounds and restricted them to a reservation south of the Arkansas River. They attempted to hold their traditional lands at Smoky Hill, but the campaigns of General Philip Sheridan foiled these efforts; most notably, after the Battle of Beecher's Island, many Dog Soldiers were forced to retreat south of the Arkansas River.

In the spring of 1867, they returned north with the intention of joining Red Cloud in Powder River country. They were attacked by General Eugene Carr, however, and instead began raiding settlements on Smoky Hill in revenge. Eventually, the Dog Soldiers fled west into Colorado, under the guidance of Chief Tall Bull. They were attacked by a force composed of Pawnee mercenaries and American cavalry; almost everyone, including Tall Bull, died in the attack near Summit Springs.

Modern Dog Soldiers

Today the Dog Soldiers society is making a comeback in such areas as the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana and the Cheyenne-Arapaho Indian Reservation in Oklahoma.

Notable Cheyenne

- Ben Nighthorse Campbell, Northern Cheyenne, Former Senator, State of Colorado, United States Congress

- W. Richard West Jr., Southern Cheyenne, Founding Director, Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian

- Suzan Shown Harjo, Southern Cheyenne and Muscogee (Creek), Founding Trustee, Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian; President, Morning Star Institute (A Native rights advocacy organization based in Washington DC).

- Chris Eyre, Southern Cheyenne and Southern Arapaho, Movie Director, notable film: "Smoke Signals."

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Hoig 1980, p. 11.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Greene 2004, p. 9.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hoig 1980, p. 8.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Hoig 1980, p. 12.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hyde 1968, p. 336.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Hyde 1968, p. 337.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Greene 2004, p. 26.

- ↑ Greene 2004, p. 23.

- ↑ Greene 2004, p. 24.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Greene 2004, p. 27.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Hyde 1968, p. 159.

- ↑ Hoig 1980, p. 30.

- ↑ Hyde 1968, p. 74.

- ↑ Hoig 1980, pp. 48-49.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Hyde 1968, p. 335.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 Hoig 1980, p. 49.

- ↑ Hyde 1968, p. 75.

- ↑ Hyde 1968, p. 79.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 Hyde 1968, p. 338.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Hyde 1968, p. 97.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Hyde 1968, p. 339.

- ↑ Hyde 1968, p. 96.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Hoig 1980, p. 85.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Greene, Jerome A. (2004). Washita, The Southern Cheyenne and the U.S. Army. Campaigns and Commanders Series, vol. 3. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806135514.

- Hoig, Stan. (1980). The Peace Chiefs of the Cheyennes. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1573-4.

- Hyde, George E. (1968). Life of George Bent Written from His Letters. Ed. by Savoie Lottinville. Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0-8061-1577-7.

- Brown, Dee, Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee.

- Sandoz, Marie, Cheyenne Autumn. ISBN 0-8032-9212-0

- Stands in Timber, John, Cheyenne Memories. ISBN 0-300-07300-3

- Grinnell, George Bird. "The Fighting Cheyenne." ISBN 0-87928-075-1

- Hoebel, E.A. "The Cheyennes."

- Broome, Jeff Dog Soldier Justice: The Ordeal of Susanna Alderdice in the Kansas Indian War, Lincoln, Kansas: Lincoln County Historical Society, 2003. ISBN 0-9742546-1-4

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.