Cassowary

| Cassowary

| ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Southern Cassowary

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Casuarius casuarius |

Cassowary is the common name for any of the very large, flightless [bird]]s comprising the ratite genus Casuarius, characterized by powerful legs with three-toed feet with sharp claws, a long dagger-like claw on the inner toe, small wings, a featherless head, and a horny crest on the head. These ratites are native to New Guinea, northeastern Australia, and various other islands in the Australo-Papuan region.

There are three extant species recognized today and one extinct. The southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius) is the third largest flightless bird on the planet, smaller only than the ostrich and emu.

They are a keystone species of rain forests because they eat fallen fruit whole and distribute seeds across the jungle floor via excrement.[2]

Cassowaries are very shy, but when disturbed, they are capable of inflicting fatal injuries to dogs and children.

Description

The Northern and Dwarf Cassowaries are not well known. All cassowaries are usually shy birds of the deep forest, adept at disappearing long before a human knows they are there. Even the more accessible Southern Cassowary of the far north Queensland rain forests is not well understood.

Females are bigger and more brightly coloured. Adult Southern Cassowaries are Template:Convert/to(-) tall, although some females may reach 2 meters (79 in)[3], and weigh 58.5 kilograms (129 lb)[4].

All cassowaries have feathers that consist of a shaft and loose barbules. They do not have retrices (tail feathers), a preen gland. Cassowaries have small wings with 5-6 large remeges. These are reduced to stiff, keratinous, quills, like porcupine quills, with no barbs[4]. There is a claw on each second finger[5]. The furcula and coracoid are degenerate, and their palatal bones and sphenoid bones touch each other.[2] A cassowary's three-toed feet have sharp claws. The second toe, the inner one in the medial position, sports a dagger-like claw that is 125 millimeters (4.9 in) long[4]. This claw is particularly fearsome since cassowaries sometimes kick humans and animals with their enormously powerful legs (see Cassowary Attacks, below). Cassowaries can run up to 50 km/h (31 mph) through the dense forest. They can jump up to 1.5 meters (4.9 ft) [citation needed]and they are good swimmers, crossing wide rivers and swimming in the sea as well[5].

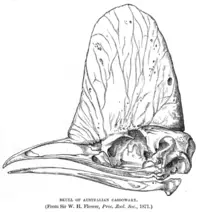

All three species have horn-like crests called casques on their heads, up to 18 cm (7.1 in).[2] These consist of "a keratinous skin over a core of firm, cellular foam-like material".[6] Several purposes for the casques have been proposed. One possibility is that they are secondary sexual characteristics. Other suggestions include that they are used to batter through underbrush, as a weapon for dominance disputes, or as a tool for pushing aside leaf litter during foraging. The latter three are disputed by biologist Andrew Mack, whose personal observation suggests that the casque amplifies deep sounds.[7] However, the earlier article by Crome and Moore says that the birds do lower their heads when they are running "full tilt through the vegetation, brushing saplings aside and occasionally careering into small trees. The casque would help protect the skull from such collisions."[6] Mack and Jones also speculate that the casques play a role in either sound reception or acoustic communication. This is related to their discovery that at least the Dwarf Cassowary and Southern Cassowary produce very-low frequency sounds, which may aid in communication in dense rainforest.[7] This "boom" is the lowest known bird call, and is on the edge of human hearing.[8]

the tropical forests of New Guinea and nearby islands, and northeastern Australia[9].

Taxonomy and evolution

Cassowaries (from the Malay name kesuari)[10] are part of the ratite group, which also includes the Emu, rheas, Ostrich, and kiwis, and the extinct moas and elephant birds. There are three extant species recognized today and one extinct:

- Casuarius casuarius, Southern Cassowary or Double-wattled Cassowary, found in southern New Guinea, northeastern Australia, and the Aru Islands,[9] mainly in lowlands.

- Casuarius bennetti, Dwarf Cassowary or Bennett's Cassowary, found in New Guinea, New Britain, and on Yapen,[9] mainly in highlands.

- Casuarius unappendiculatus, Northern Cassowary or Single-wattled Cassowary, found in the northern and western New Guinea, and Yapen,[9][11] mainly in lowlands.

- Casuarius lydekki Extinct[1]

Presently, most authorities consider the above monotypic, but several subspecies have been described of each (some have even been suggested as separate species, e.g. C. (b) papuanus).[11] It has proven very difficult to confirm the validity of these due to individual variations, age-related variations, the relatively few available specimens (and the bright skin of the head and neck – the basis of which several subspecies have been described – fades in specimens), and that locals are known to have traded live cassowaries for hundreds, if not thousands, of years, some of which are likely to have escaped/been deliberately introduced to regions away from their origin.[11]

The evolutionary history of cassowaries, as of all ratites, is not well known. A fossil species was reported from Australia, but for reasons of biogeography this assignment is not certain and it might belong to the prehistoric "emuwaries", Emuarius, which were cassowary-like primitive emus.

Behavior

Cassowaries are solitary birds except during courtship, egg-laying, and sometimes around ample food supplies.[2]

Reproductive

Females lay three to eight large, pale green-blue eggs in each clutch into a prepared heap of leaf litter.[2] These eggs measure about 9 by 14 centimeters (3.5 in × 5.5 in)

— only Ostrich and Emu eggs are larger. The female does not care for the eggs or the chicks; the male incubates the eggs for 50-52 days, removing or adding litter to regulate the temperature, then protects the brown-striped chicks for nine months, defending them fiercely against all potential predators, including humans.[2]

Diet

Cassowaries feed mainly on fruits, though all species are truly omnivorous and will take a range of other plant food including shoots, grass seeds and fungi in addition to invertebrates and small vertebrates.

Cassowaries are frugivorous; fallen fruit, such as the cassowary plum and fruit on low branches is the mainstay of their diet. They also eat fungi, snails, insects, frogs, and snakes. They are a keystone species of rain forests because they eat fallen fruit whole and distribute seeds across the jungle floor via excrement.[2]

Distribution and habitat

Cassowaries are native to the humid rainforests of New Guinea and nearby smaller islands, and northeastern Australia.[9] They will, however, venture out into palm scrub, grassland, savanna, and swamp forest.[2] It is unclear if some islands populations are natural or the result of trade in young birds by natives.

Threats

The Southern Cassowary is endangered in Queensland, Australia. Kofron and Chapman (2006) assessed the decline of this species. They found that, of the former cassowary habitat, only 20 - 25% remains. They stated that habitat loss and fragmentation is the primary cause of decline[12]. They then studied 140 cases of cassowary mortality and found that motor vehicle strikes accounted for 55% of them, and dog attacks produced another 18%. Remaining causes of death included hunting (5 cases), entanglement in wire (1 case), the removal of cassowaries that attacked humans (4 cases), and natural causes (18 cases), including tuberculosis (4 cases). 15 cases were for unknown reasons[12].

Hand feeding of cassowaries poses a big threat to their survival.[13] In suburban areas the birds are more susceptible to vehicles and dogs. Contact with humans encourages Cassowaries to take most unsuitable food from picnic tables.

Feral pigs are a huge problem. They probably destroy nests and eggs; but their worst effect is as competitors for food, which could be catastrophic for the Cassowaries during lean times.

Cassowary Attacks

Cassowaries have a reputation for being dangerous to people and domestic animals. The 2007 edition of the Guinness World Records lists the cassowary as the world's most dangerous bird. During World War II American and Australian troops stationed in New Guinea were warned to steer clear of them. Many internet entries about cassowaries state that they can disembowel a man or dog with one kick, with the long second toe claw cutting the gut open. This belief has been repeated in print by authors including Gregory S. Paul (1988)[14] and Jared Diamond (1997)[15].

Research on cassowary attacks has been unable to substantiate a single claim of any cassowary disemboweling any person or animal[16].

Cassowary attacks occur every year in Queensland, Australia. Of 221 attacks studied, 150 were against humans. 75% of these were from cassowaries that had been fed by people. 71% of the time the bird chased or charged the victim. 15% of the time they kicked. Of the attacks, 73% involved the birds expecting or snatching food, 5% involved defending natural food sources, 15% involved defending themselves from attack, 7% involved defending their chicks or eggs. Of all 150 attacks there was only one human death[17].

The one documented human death caused by a cassowary was that of Phillip Mclean, aged 16 years old, and it happened on 6 April 1926. He and his brother, aged 13, were attempting to beat the cassowary to death with clubs. They were accompanied by their dog. The bird kicked the younger boy, who fell and ran away. Then the older boy struck the bird. The bird charged and knocked the older boy to the ground. While on the ground, Phillip was kicked in the neck, opening a 1.25 centimeter wound. Phillip got up and ran but died shortly afterwards from the hemorrhaging blood vessel in his neck[16].

Cassowary strikes to the abdomen are among the rarest of all, but there is one case of a dog that was kicked in the belly in 1995. The blow left no puncture, but there was severe bruising. The dog later died from an apparent intestinal rupture[16].

Role in seed dispersal and germination

Cassowaries feed on the fruits of several hundred rainforest species and usually pass viable seeds in large dense scats. They are known to disperse seeds over distances greater than a kilometre, and thus probably play an important role in the ecosystem. Germination rates for seeds of the rare Australian rainforest tree Ryparosa were found to be much higher after passing through a cassowary's gut (92% versus 4%).[18]

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Brands, S. (2008)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Davies, S. J. J. F. (2003)

- ↑ buzzle.com

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Davies, S.J.J.F. (2002) Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Davies2002" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 5.0 5.1 Harmer, S. F. & Shipley, A. E. (1899)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Crome, F., and Moore, L. (1988)

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Mack, A.L. & Jones, J (2003)

- ↑ Owen, J. (2003)

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Clements, J (2007)

- ↑ Gotch, A.T. (1995)

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Davies, S. J. J. F. (2002)

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Kofron, C. P. & Chapman, A. (2006)

- ↑ Borrell 2008.

- ↑ Paul, G. S. (1988)

- ↑ Diamond, J. (2008)

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Kofron, C. P. (2003)

- ↑ Kofron, C. P. (1999)

- ↑ Weber, B.L. & Woodrow, I.E.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brands, Sheila (Aug 14 2008). Systema Naturae 2000 / Classification, Genus Casuarius. Project: The Taxonomicon. Retrieved Feb 04 2009.

- Buzzle.com The Cassowary Bird

- Clark, Philip (ed), (1990) Stay in Touch The Sydney Morning Herald, 5 November 1990. Cites "authorities" for the death claim.

- (2007) The Clements Checklist of the Birds of the World, 6, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978 0 8014 4501 9.

- Crome, F., and L. Moore. (1988) The cassowary’s casque. Emu 88:123–124.

- Davies, S. J. J. F. (2002). Ratites and Tinamous. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0 19 854996 2

- Davies, S.J.J.F.. (2003). "Cassowaries". Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia (2) 8 Birds I Tinamous and Ratites to Hoatzins: 75-77. Ed. Hutchins, Michael. Farmington Hills, MI: Gale Group.

- Diamond, J. (March 1997 pg 165). Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies. W.W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-03891-2. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

- [1979] (1995) "Cassowaries", Latin Names Explained. A Guide to the Scientific Classifications of Reptiles, Birds & Mammals. New York, NY: Facts on File, 178-179. ISBN 0 8160 3377 3.

- (1899) The Cambridge Natural History. Macmillan and Co, 35-36.

- Kofron, Christopher P. (1999) "Attacks to humans and domestic animals by the southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius johnsonii) in Queensland, Australia

- Kofron, Christopher P. (2003) "Case histories of attacks by the southern cassowary in Queensland" Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 49(1) 335-338

- Kofron, Christopher P., Chapman, Angela. (2006) "Causes of mortality to the endangered Southern Cassowary Casuarius casuariusjohnsonii in Queensland, Australia." Pacific Conservation Biology vol. 12: 175-179

- Mack, A.L. & Jones, J (2003) Low-frequency vocalizations by cassowaries (Casuarius spp.) The Auk 120(4):1062–1068

- Owen, J. (2003). Does Rain Forest Bird "Boom" Like a Dinosaur?. National Geographic News.

- Paul, Gregory S. (1988) Predatory Dinosaurs of the World. Simon and Schuster, New York, USA. pg. 364, 464pp.

- Readers' Digest, June 2006 issue.

- Underhill, D (1993) Australia's Dangerous Creatures, Reader's Digest, Sydney, New South Wales, ISBN 0-86438-018-6

- Weber, B.L. & Woodrow, I.E. Functional Plant Biology "Cassowary frugivory, seed defleshing and fruit fly infestation influence the transition from seed to seedling in the rare Australian rainforest tree, Ryparosa sp. nov. 1 (Achariaceae)." 31: 505-516

See also

- Fauna of Australia

- Fauna of New Guinea

External links

- C4 - Cassowary Conservation based in Mission Beach

- The cassowary (photo essay)

- Dave Kimble's Rainforest Photo Catalog

- The Cassowary Bird

- ARKive - images and movies of the southern cassowary (Casuarius casuarius)

- Cassowary videos on the Internet Bird Collection

- Cassowaries in Mission Beach

- Mission Beach Cassowaries - Places to spot them

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.