Difference between revisions of "Cairo Geniza" - New World Encyclopedia

m |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (32 intermediate revisions by 4 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

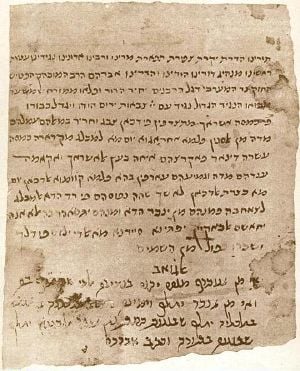

| − | The '''Cairo | + | [[image:Cairo Genizah Fragment.jpg|thumb|Original letter of Abraham, the son of [[Maimonides]] and head of the Egyptian Jewish community, found in the Cairo geniza]] |

| + | The '''Cairo geniza''' was a storeroom in a [[synagogue]] in [[Cairo, Egypt]], in which almost 200,000 [[Judaism|Jewish]] medieval manuscripts were discovered. It is considered among the greatest archaeological finds of the modern era, providing many unique insights into Jewish and [[Middle East]]ern history during a period of more than a thousand years. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Although the existence of the ''geniza'' (a [[Hebrew]] word meaning a "hiding place" for worn, damaged, or unauthorized documents) was known from the mid-nineteenth century, the Jewish scholar [[Solomon Schechter]] is generally credited with uncovering and analyzing the treasure trove of medieval documents that lay there, many untouched for centuries, beginning in 1896. The vast collection came to be housed in several university libraries and received careful study over the next century, revealing a great deal of information valuable both to the religious history of [[Judaism]] and to the general study of Middle Eastern society in the medieval period. Among the geniza's treasures were the first known copy of the Book of [[Ecclesiasticus]] in Hebrew, documents related to the history of the [[Karaite Jews]] and [[Khazars]], Talmudic and Jewish liturgical works, Arabic poetry and medical texts, legal ''responsa'' and philosophical writings, many personal and business documents, and the so-called [[Zadokite Fragments]], which were later also discovered among the [[Dead Sea Scrolls]]. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | The term "Cairo Geniza" also refers to a wider collection of documents, including those found at the ''geniza'' of [[Ben Ezra Synagogue]] itself, as well as discarded documents buried in the Basatin cemetery east of Old Cairo, and a number of related texts bought in the Cairo antiquities market in the later nineteenth century. | ||

== Discovery == | == Discovery == | ||

| − | + | A ''geniza'' is a storeroom or depository in a [[synagogue]], a literary [[cemetery]] in which worn-out scriptures are placed and heretical or disgraced Hebrew writings are stored so as to prevent their circulation. The Cairo geniza was of medieval origin, as the Jews of the area bought and renovated a destroyed [[Coptic church]] in 882, turning it into the Ben Ezra Synagogue. Cairo was a prominent center of Middle Eastern political, economic, and cultural life, and the Jewish community of Cairo consequently was a very significant one. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | [[Image:Jacob Saphir portrait.jpg|thumb|130px|Jacob Shaphir wrote of the Cairo geniza's potential in the mid-eighteenth century.]] | |

| − | + | The German traveler and book dealer [[Simon von Geldern]] is the first known western visitor to the Cairo geniza, having visited the Ben Ezra Synagogue in 1753 and mentioning the geniza in his 1773 book, ''The Israelites on Mount Horeb''. However, local [[superstition]] prevented von Geldern from examining the geniza's contents. The potential of the geniza as a significant subject of research was first recognized by the Jewish writer and traveler [[Jacob Saphir]] in the mid 1800s. After growing up in [[Safed]], in 1848, he was commissioned by the Jewish community of [[Jerusalem]] to collect [[alms]] for the city's poor from the Jewish residents of the countries to the south, and made several subsequent journeys to [[Cairo]]. In his ''Eben Sappir,'' he describes how he spent two days ferreting among the geniza's ancient books and papers until the dust and ashes of the room caused him to become ill. "Who knows what may yet be beneath?" he asked. In the late nineteenth century, Russian Jews Abraham Firkovich and Albert Harkavy succeeded in obtaining documents from a nearby Karaite geniza, in an effort to research the history of [[Karaite Judaism]]. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | The Cairo geniza seems to have become virtually lost in the following decades. In 1888, the collector and author [[Elkan Nathan Adler]] visited the Ben Ezra Synagogue but did not succeed in seeing more than a recess in the upper part of a wall containing an old scroll of the [[Book of Ezra]] and a few other ancient manuscripts. Adler was informed that all old manuscripts were buried in the Jewish cemetery at Basatin. The normal practice for genizas was to periodically remove the contents and bury them in a cemetery, and apparently the geniza had been sealed after one of these removals. | ||

| − | The | + | The English archaeologist [[Henry Archibald Sayce]], who wintered in Cairo for reasons of his health, also visited the synagogue and likewise found that many of the geniza's contents had been buried. However, Sayce was able to acquire many fragments from the synagogue's caretakers, which were later stored in the Bodleian Library of [[Oxford University]]. Other libraries made similar acquisitions. The American [[Cyrus Adler]] secured about 40 pieces from a dealer in 1891, and additional documents were purchased on the antiquities market by various other researches. |

| − | + | When the synagogue was renovated c. 1889, the old storeroom was rediscovered, being a secret chamber approached by climbing a ladder and entering through a hole in the wall. During E.N. Adler's subsequent visits to Cairo until 1896, he collected and brought over 25,000 Genizah manuscript fragments back to [[England]]. His greatest find took place in January 1896 under the escort of the synagogue's [[chief rabbi]], Rafaïl ben Shimon ha-Kohen, who allowed him to take away with him a sack containing all the parchment and paper fragments they had been able to gather in about four hours. Some of these turned out to be of exceptional interest, and were published shortly afterward. | |

| − | + | [[Image:Solomon Schechter.jpg|thumb|[[Solomon Schechter]] works on the documents of the Cairo geniza]] | |

| − | + | It was the identification of a text of ''[[Ben Sira]]'' among the Bodleian fragments which induced [[Solomon Schechter]] to proceed to Cairo in the autumn on 1896 and bring back with him practically the entire written contents of the geniza. Two researchers associated with [[Cambridge University]], [[Agnes and Margaret Smith]], showed Schechter, who at the time was a professor of Talmudic and rabbinical literature at Cambridge, several intriguing fragments from the geniza. Schechter was able to determine that they were part of the previously unknown [[Hebrew]] original of Ben Sira's ''Book of Wisdom,'' the Greek version of which had been accepted into the Christian canon and was known as ''[[Ecclesiasticus]]'' in Catholic bibles. No Hebrew version of this work was previously known. Schechter then received a grant enabling him to lead an expedition to Egypt, where he carefully went through the Cairo geniza and returned to Cambridge with thousands of new documents. These now constitute the bulk of the collection at the Cambridge University Library. Schechter's subsequent publications revealed the great value of the texts, which has since received careful and exhaustive study. | |

| − | + | The documents of the Cairo geniza have now been archived in various American and European libraries. The [[Charles Taylor (scholar)|Taylor]]-Schechter collection in the [[University of Cambridge]] runs to 140,000 manuscripts; there are a further 40,000 manuscripts at the [[Jewish Theological Seminary of America]]. Also, the [[John Rylands University Library]] in Manchester, Egnland holds a collection of over 11,000 fragments, which are currently being digitized and uploaded to an online archive. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | + | == Contents and significance == | |

| + | [[Image:BenEzraAnnex.jpg|thumb|250px|Modern annex at the Ben Ezra Synagogue in Cairo.]] | ||

| + | The documents of the Cairo geniza were written from about 870 C.E. to as late as 1880. Although none of them can be considered truly ancient, many represent copies of ancient texts, some of which were not previously known and have proven to be of great significance. Many of the documents are secular in nature, revealing previously unknown facts about Jewish and Egyptian life over a period of more than a millennium. In terms of importance, their discovery is often likened to the later and much more famous discovery of the [[Dead Sea Scrolls]]. | ||

| − | + | Schecter's work on [[Ben Sirah]] brought considerable attention to the find just before the turn of the twentieth century. His ''Saadyana'' (1903) revealed substantial new light from the geniza on the work of the great medieval Jewish [[rabbi]] and [[philosopher]] [[Saadia Gaon]]. His ''[[Zakokite fragments|Documents of Jewish Sectaries]]'' (1910), dealing with a previously unknown first-century sect now thought to be part of the [[Essenes]], proved especially significant after fragments of the same document turned up among the [[Dead Sea Scrolls]], proving that the documents which Schechter found at the geniza were indeed copies of texts from around the turn of the [[Common Era]], as he had suspected. | |

| − | The | + | The geniza also contained copies of Greek translations of the [[Bible]] by [[Aquila of Sinope]], who originally worked c. 130 C.E. Ancient Jewish liturgical prayers of both [[Babylonia]]n and [[spain|Spanish]] origin were also uncovered, as well as a great deal of material dealing with the history and traditions of [[Karaites]]. A tenth-century letter from [[Kiev]] constitutes the earliest known evidence of Jews living in the [[Ukraine]]. The geniza also shone new light on the conversion to Judaism of the kingdom of the [[Khazars]] from the ninth century onward. [[Yiddish]] letters and poems from the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries were also discovered at the geniza. |

| − | + | Many of the geniza documents were written in the [[Arabic language]] using the [[Hebrew alphabet]]. As Hebrew was considered the language of God by the Jews, the texts could not be destroyed even long after they had served their purpose. The documents are invaluable as evidence for how colloquial Arabic of this period was spoken and understood. | |

| − | The | + | The importance of these materials for reconstructing the social and economic history of medieval Egypt and the Middle East cannot be overemphasized. For example, the geniza documents include a unique romantic tale of Umayyid caliph [[Al-Walid II]], from the mid-eighth century. They also contain the only copies of some of the pharmacological works of eleventh-century physician Ahmed [[Ibn Al-Jazzar]]. The geniza provided a great deal of previously unknown information about the rule of the Ayyubid sultans in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, showing as well the role that the Jews of the period played in Cairo's life and culture. They show, for instance, that the Jews of Cairo practiced the same trades as their [[Muslim]] and [[Christian]] neighbors, including farming. They also bought, sold, and rented properties to and from their [[Gentile]] contemporaries. |

| − | + | An index created by the scholar [[Shelomo Dov Goitein]] covers about 35,000 individuals named in the documents, including about 350 "prominent people," including [[Maimonides]] (who moved to Cairo late in life) and his son [[Avraham son of Rambam|Abraham]]; 200 "better known families;" and mentions 450 professions and 450 trade goods. Goitein identified material from [[Egypt]], [[Palestine]], [[Lebanon]], [[Syria]], [[Tunisia]], [[Sicily]], and even [[India]]. Cities mentioned range from [[Samarkand]] in Central Asia to [[Seville]] and [[Sijilmasa]], [[Morocco]] to the west; from [[Aden]] north to [[Constantinople]]; Europe not only is represented by the Mediterranean port cities of [[Narbonne]], [[Marseilles]], [[Genoa]], and [[Venice]], but even [[Kiev]] and [[Rouen]] are occasionally mentioned. | |

| − | + | The materials include a vast number of books, most of them fragments, which Goitein estimated number 250,000 leaves, including parts of Jewish religious writings and fragments from the [[Qur'an]]. Goitein also found that the number of documents dropped in number about the 1266 and saw a rise around 1500, when the local community was increased by [[Spanish expulsion|refugees from Spain]]. It was these Spanish immigrants who brought to Cairo several documents that shed important light on the history of [[Khazaria]] and [[Kievan Rus]]. | |

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

*[[Dead Sea Scrolls]] | *[[Dead Sea Scrolls]] | ||

| − | *[[ | + | *[[Solomon Schechter]] |

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | * | + | * Cohen, Mark R. ''The Voice of the Poor in the Middle Ages: An Anthology of Documents from the Cairo Geniza''. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005. ISBN 9780691092713. |

| + | * Goitein, S. D., and Paula Sanders. ''A Mediterranean Society; The Jewish Communities of the Arab World As Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza''. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967. ISBN 9780520056473. | ||

| + | * Hunter, Erica C. D., Rebecca J. W. Jefferson, and Geoffrey Khan. ''Published Material from the Cambridge Genizah Collections: A Bibliography 1980-1997''. Cambridge, UK: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 2004. ISBN 9780521750868. | ||

| + | * Kahle, Paul. ''The Cairo Geniza''. Oxford: Blackwell, 1959. {{OCLC|9617721}} | ||

| + | * Olszowy-Schlanger, Judith. ''Karaite Marriage Documents from the Cairo Geniza: Legal Tradition and Community Life in Medieval Egypt and Palestine''. Etudes sur le judaïsme médiéval, t. 20. Leiden: Brill, 1998. ISBN 9789004108868. | ||

| + | * Reif, Stefan C., and Shulamit Reif. ''The Cambridge Genizah Collections: Their Contents and Significance''. Cambridge University Library Genizah series, 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 9780521813617. | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved November 25, 2023. | |

| − | *[http://www.princeton.edu/~geniza/ Princeton Geniza Project | + | *[http://www.princeton.edu/~geniza/ Princeton Geniza Project ] |

| − | |||

*[http://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/Taylor-Schechter/ University of Cambridge Taylor-Shechter Geniza Research Unit] | *[http://www.lib.cam.ac.uk/Taylor-Schechter/ University of Cambridge Taylor-Shechter Geniza Research Unit] | ||

*[http://sceti.library.upenn.edu/genizah/ Penn/Cambridge Genizah Fragment Project] | *[http://sceti.library.upenn.edu/genizah/ Penn/Cambridge Genizah Fragment Project] | ||

| Line 55: | Line 63: | ||

[[Category:philosophy and religion]] | [[Category:philosophy and religion]] | ||

[[Category:literature]] | [[Category:literature]] | ||

| − | |||

[[Category:Judaism]] | [[Category:Judaism]] | ||

| − | [[Category:history]] | + | [[Category:history of the Middle East]] |

{{credit|256820353}} | {{credit|256820353}} | ||

Latest revision as of 18:19, 25 November 2023

The Cairo geniza was a storeroom in a synagogue in Cairo, Egypt, in which almost 200,000 Jewish medieval manuscripts were discovered. It is considered among the greatest archaeological finds of the modern era, providing many unique insights into Jewish and Middle Eastern history during a period of more than a thousand years.

Although the existence of the geniza (a Hebrew word meaning a "hiding place" for worn, damaged, or unauthorized documents) was known from the mid-nineteenth century, the Jewish scholar Solomon Schechter is generally credited with uncovering and analyzing the treasure trove of medieval documents that lay there, many untouched for centuries, beginning in 1896. The vast collection came to be housed in several university libraries and received careful study over the next century, revealing a great deal of information valuable both to the religious history of Judaism and to the general study of Middle Eastern society in the medieval period. Among the geniza's treasures were the first known copy of the Book of Ecclesiasticus in Hebrew, documents related to the history of the Karaite Jews and Khazars, Talmudic and Jewish liturgical works, Arabic poetry and medical texts, legal responsa and philosophical writings, many personal and business documents, and the so-called Zadokite Fragments, which were later also discovered among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

The term "Cairo Geniza" also refers to a wider collection of documents, including those found at the geniza of Ben Ezra Synagogue itself, as well as discarded documents buried in the Basatin cemetery east of Old Cairo, and a number of related texts bought in the Cairo antiquities market in the later nineteenth century.

Discovery

A geniza is a storeroom or depository in a synagogue, a literary cemetery in which worn-out scriptures are placed and heretical or disgraced Hebrew writings are stored so as to prevent their circulation. The Cairo geniza was of medieval origin, as the Jews of the area bought and renovated a destroyed Coptic church in 882, turning it into the Ben Ezra Synagogue. Cairo was a prominent center of Middle Eastern political, economic, and cultural life, and the Jewish community of Cairo consequently was a very significant one.

The German traveler and book dealer Simon von Geldern is the first known western visitor to the Cairo geniza, having visited the Ben Ezra Synagogue in 1753 and mentioning the geniza in his 1773 book, The Israelites on Mount Horeb. However, local superstition prevented von Geldern from examining the geniza's contents. The potential of the geniza as a significant subject of research was first recognized by the Jewish writer and traveler Jacob Saphir in the mid 1800s. After growing up in Safed, in 1848, he was commissioned by the Jewish community of Jerusalem to collect alms for the city's poor from the Jewish residents of the countries to the south, and made several subsequent journeys to Cairo. In his Eben Sappir, he describes how he spent two days ferreting among the geniza's ancient books and papers until the dust and ashes of the room caused him to become ill. "Who knows what may yet be beneath?" he asked. In the late nineteenth century, Russian Jews Abraham Firkovich and Albert Harkavy succeeded in obtaining documents from a nearby Karaite geniza, in an effort to research the history of Karaite Judaism.

The Cairo geniza seems to have become virtually lost in the following decades. In 1888, the collector and author Elkan Nathan Adler visited the Ben Ezra Synagogue but did not succeed in seeing more than a recess in the upper part of a wall containing an old scroll of the Book of Ezra and a few other ancient manuscripts. Adler was informed that all old manuscripts were buried in the Jewish cemetery at Basatin. The normal practice for genizas was to periodically remove the contents and bury them in a cemetery, and apparently the geniza had been sealed after one of these removals.

The English archaeologist Henry Archibald Sayce, who wintered in Cairo for reasons of his health, also visited the synagogue and likewise found that many of the geniza's contents had been buried. However, Sayce was able to acquire many fragments from the synagogue's caretakers, which were later stored in the Bodleian Library of Oxford University. Other libraries made similar acquisitions. The American Cyrus Adler secured about 40 pieces from a dealer in 1891, and additional documents were purchased on the antiquities market by various other researches.

When the synagogue was renovated c. 1889, the old storeroom was rediscovered, being a secret chamber approached by climbing a ladder and entering through a hole in the wall. During E.N. Adler's subsequent visits to Cairo until 1896, he collected and brought over 25,000 Genizah manuscript fragments back to England. His greatest find took place in January 1896 under the escort of the synagogue's chief rabbi, Rafaïl ben Shimon ha-Kohen, who allowed him to take away with him a sack containing all the parchment and paper fragments they had been able to gather in about four hours. Some of these turned out to be of exceptional interest, and were published shortly afterward.

It was the identification of a text of Ben Sira among the Bodleian fragments which induced Solomon Schechter to proceed to Cairo in the autumn on 1896 and bring back with him practically the entire written contents of the geniza. Two researchers associated with Cambridge University, Agnes and Margaret Smith, showed Schechter, who at the time was a professor of Talmudic and rabbinical literature at Cambridge, several intriguing fragments from the geniza. Schechter was able to determine that they were part of the previously unknown Hebrew original of Ben Sira's Book of Wisdom, the Greek version of which had been accepted into the Christian canon and was known as Ecclesiasticus in Catholic bibles. No Hebrew version of this work was previously known. Schechter then received a grant enabling him to lead an expedition to Egypt, where he carefully went through the Cairo geniza and returned to Cambridge with thousands of new documents. These now constitute the bulk of the collection at the Cambridge University Library. Schechter's subsequent publications revealed the great value of the texts, which has since received careful and exhaustive study.

The documents of the Cairo geniza have now been archived in various American and European libraries. The Taylor-Schechter collection in the University of Cambridge runs to 140,000 manuscripts; there are a further 40,000 manuscripts at the Jewish Theological Seminary of America. Also, the John Rylands University Library in Manchester, Egnland holds a collection of over 11,000 fragments, which are currently being digitized and uploaded to an online archive.

Contents and significance

The documents of the Cairo geniza were written from about 870 C.E. to as late as 1880. Although none of them can be considered truly ancient, many represent copies of ancient texts, some of which were not previously known and have proven to be of great significance. Many of the documents are secular in nature, revealing previously unknown facts about Jewish and Egyptian life over a period of more than a millennium. In terms of importance, their discovery is often likened to the later and much more famous discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Schecter's work on Ben Sirah brought considerable attention to the find just before the turn of the twentieth century. His Saadyana (1903) revealed substantial new light from the geniza on the work of the great medieval Jewish rabbi and philosopher Saadia Gaon. His Documents of Jewish Sectaries (1910), dealing with a previously unknown first-century sect now thought to be part of the Essenes, proved especially significant after fragments of the same document turned up among the Dead Sea Scrolls, proving that the documents which Schechter found at the geniza were indeed copies of texts from around the turn of the Common Era, as he had suspected.

The geniza also contained copies of Greek translations of the Bible by Aquila of Sinope, who originally worked c. 130 C.E. Ancient Jewish liturgical prayers of both Babylonian and Spanish origin were also uncovered, as well as a great deal of material dealing with the history and traditions of Karaites. A tenth-century letter from Kiev constitutes the earliest known evidence of Jews living in the Ukraine. The geniza also shone new light on the conversion to Judaism of the kingdom of the Khazars from the ninth century onward. Yiddish letters and poems from the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries were also discovered at the geniza.

Many of the geniza documents were written in the Arabic language using the Hebrew alphabet. As Hebrew was considered the language of God by the Jews, the texts could not be destroyed even long after they had served their purpose. The documents are invaluable as evidence for how colloquial Arabic of this period was spoken and understood.

The importance of these materials for reconstructing the social and economic history of medieval Egypt and the Middle East cannot be overemphasized. For example, the geniza documents include a unique romantic tale of Umayyid caliph Al-Walid II, from the mid-eighth century. They also contain the only copies of some of the pharmacological works of eleventh-century physician Ahmed Ibn Al-Jazzar. The geniza provided a great deal of previously unknown information about the rule of the Ayyubid sultans in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, showing as well the role that the Jews of the period played in Cairo's life and culture. They show, for instance, that the Jews of Cairo practiced the same trades as their Muslim and Christian neighbors, including farming. They also bought, sold, and rented properties to and from their Gentile contemporaries.

An index created by the scholar Shelomo Dov Goitein covers about 35,000 individuals named in the documents, including about 350 "prominent people," including Maimonides (who moved to Cairo late in life) and his son Abraham; 200 "better known families;" and mentions 450 professions and 450 trade goods. Goitein identified material from Egypt, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria, Tunisia, Sicily, and even India. Cities mentioned range from Samarkand in Central Asia to Seville and Sijilmasa, Morocco to the west; from Aden north to Constantinople; Europe not only is represented by the Mediterranean port cities of Narbonne, Marseilles, Genoa, and Venice, but even Kiev and Rouen are occasionally mentioned.

The materials include a vast number of books, most of them fragments, which Goitein estimated number 250,000 leaves, including parts of Jewish religious writings and fragments from the Qur'an. Goitein also found that the number of documents dropped in number about the 1266 and saw a rise around 1500, when the local community was increased by refugees from Spain. It was these Spanish immigrants who brought to Cairo several documents that shed important light on the history of Khazaria and Kievan Rus.

See also

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cohen, Mark R. The Voice of the Poor in the Middle Ages: An Anthology of Documents from the Cairo Geniza. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2005. ISBN 9780691092713.

- Goitein, S. D., and Paula Sanders. A Mediterranean Society; The Jewish Communities of the Arab World As Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1967. ISBN 9780520056473.

- Hunter, Erica C. D., Rebecca J. W. Jefferson, and Geoffrey Khan. Published Material from the Cambridge Genizah Collections: A Bibliography 1980-1997. Cambridge, UK: Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 2004. ISBN 9780521750868.

- Kahle, Paul. The Cairo Geniza. Oxford: Blackwell, 1959. OCLC 9617721

- Olszowy-Schlanger, Judith. Karaite Marriage Documents from the Cairo Geniza: Legal Tradition and Community Life in Medieval Egypt and Palestine. Etudes sur le judaïsme médiéval, t. 20. Leiden: Brill, 1998. ISBN 9789004108868.

- Reif, Stefan C., and Shulamit Reif. The Cambridge Genizah Collections: Their Contents and Significance. Cambridge University Library Genizah series, 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 9780521813617.

External links

All links retrieved November 25, 2023.

- Princeton Geniza Project

- University of Cambridge Taylor-Shechter Geniza Research Unit

- Penn/Cambridge Genizah Fragment Project

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.