Banneker, Benjamin

| (24 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | {{epname}} | + | {{epname|Banneker, Benjamin}} |

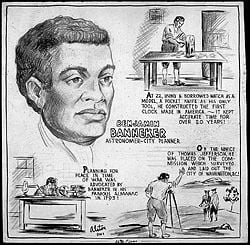

| − | [[Image:ben banneker.jpg|thumb| | + | [[Image:ben banneker.jpg|thumb|250px|Some highlights of Benjamin Banneker's life, as depicted by Charles Alston, 1943.]] |

| − | + | '''Benjamin Banneker,''' originally '''Banna Ka,''' or '''Bannakay''' (November 9, 1731 – October 9, 1806) was a free [[African American]] [[mathematician]], [[astronomer]], [[clockmaker]], and [[publisher]]. He was America's first African American scientist and a champion of [[civil rights]] and world [[peace]]. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | == Life == | ||

| + | Benjamin Banneker was born near Ellicot City, [[Maryland]], on November 9, 1731. He was the first of three children to Robert, a freed [[slave]] from West [[Africa]], and Mary Banneky, of English-African descent. Mary was the second of four daughters born to Molly Welsh, an [[English]] [[indentured servant]] who had earned her freedom by 1690. Molly rented a [[farm]], raised [[corn]] and [[tobacco]], and became a landowner. She purchased and freed two African [[slave]]s, one of whom (named Bannka or Banna Ka) she married. Bannka was the son of a [[Gambia]]n king who was captured by slave traders in Africa. His name, derived from the [[Wolof]] dialect of the [[Senegal]]-Gambia region of West Africa, connoted a person of sweet or peaceful disposition (Bedini, 1999). This trait seems to have characterized his grandson's personality as well. | ||

| − | + | Benjamin Banneker learned to read and write from his grandmother, Molly, who encouraged him to practice reading from a large [[Bible]] she had ordered from England. He attended a one-room schoolhouse near his home, where he was instructed by a [[Quaker]] schoolmaster. Acquiring a thirst for [[knowledge]], Banneker began to educate himself in [[mathematics]] and became intrigued by the solving of [[arithmetic]]al puzzles. Given that few people of African descent in the colonies were not subject to some form of slavery, his situation was unusual and he eventually played a key role in the [[abolition movement]]. | |

| − | + | Banneker's life and fortunes became linked with the Ellicots, a family of [[Quaker]] millers, who migrated from [[Pennsylvania]] to Maryland to pioneer the area known today as Ellicot City. The [[engineering]] methods and the mechanical workings of the grist [[mill]]s built by the Ellicot brothers captured Banneker's interest. He soon began to associate with the Ellicots and found himself welcomed in gatherings and discussions at the Ellicot and Company Store. In time, he struck up a friendship with George Ellicot, a son of one of the original Ellicot brothers. | |

| − | Benjamin | + | George shared Benjamin's fascination with [[natural science]] and mathematics and loaned him several important books, which Banneker used to learn about surveying and astronomy. The association with the Ellicots complemented his desire to learn new skills, and he was hired by Major Andrew Ellicot to assist in surveying the [[District of Columbia]]. |

| − | + | Retiring from that project due to health problems, the aging Banneker devoted his free time to the production of six [[almanac]]s, which included calculations of celestial phenomena for the years 1792-1797. These were published with the assistance of prominent [[abolitionist]]s who saw in the talented [[astronomer]] a strong argument for the equality of all humans, regardless of [[race]]. | |

| − | Benjamin | + | Benjamin Banneker died on October 9, 1806, at age 74, in his log cabin. He never married. |

| − | + | == Accomplishments == | |

| + | === Early years === | ||

| + | In his early 20s, Banneker studied the detailed workings of a pocket watch. Such was his genius that he was able to fashion his own time piece, a mechanical clock, with carefully crafted wooden movements driven by a system of falling weights. Young Banneker became famous throughout the area. The clock continued to work, striking each hour, for more than 50 years. | ||

| − | + | At the age of 28, following his father Robert's death, Benjamin Banneker assumed ownership of the family farm and became responsible for his mother and sisters. He farmed tobacco, raised cows, and tended beehives, from which he derived much pleasure. At the age of 32, he acquired his first book, a [[bible]], in which he inscribed the date of purchase, January 4, 1763 (Bedini, 1999). | |

| − | + | The arrival of the Ellicot brothers, who established grist mills in the mid-Maryland region around the Patapsco River, marked a turning point in Banneker's life. His fascination with the construction and workings of the modern mechanical devices and the mills themselves led him to associate with the Ellicots. The latter were Quakers and staunch abolitionists who welcomed him into their circle. Banneker found himself welcomed at gatherings and discussions at the Ellicot and Company Store. | |

| − | + | Eventually, Bannaker became friends with George Ellicot, one of the sons of the mill builders, who shared his interests in mathematics and astronomy. Young George loaned him several books, as well as a telescope, which greatly improved Banneker's grasp of astronomical and planetary phenomena. Thus, he began to calculate the appearances of solar and lunar eclipses and other celestial events. By 1790, he was able to calculate an ephemeris and attempted to have it published. At this point his work came to the attention of several prominent members of the newly emerging [[Abolitionist Movement]] in both Maryland and Pennsylvania. | |

| − | Banneker | + | ===Participation in Surveying of the District of Columbia=== |

| + | In early 1791, Joseph Ellicott's brother, Andrew Ellicot, hired Banneker to assist in a survey of the boundaries of the future 10 square-mile [[Washington, D.C.|District of Columbia]], which was to contain the federal capital city (the city of Washington) in the portion of the District that was northeast of the [[Potomac River]]. Because of illness and the difficulties in helping to survey, at the age of 59, an extensive area that was largely wilderness, Banneker left the boundary survey in April, 1791, and returned to his home at Ellicott Mills to work on his ephemeris. | ||

| − | + | ===Almanacs=== | |

| − | == | + | Benjamin Banneker saw an opportunity to demonstrate what a person of African descent could achieve by publishing Almanacs in both Baltimore and Philadelphia. He had the support and encouragement of several prominent members of the Abolitionist Societies of both Pennsylvania and Maryland. Those who promoted the endeavor included Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Joseph Townsend of Harford County and Baltimore, Maryland, and Dr. Benjamin Rush, among others. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Following a life journey that would be echoed by others after him including [[Martin Luther King Jr.]], and | + | The yearly Almanac was a popular book during the eighteenth century in the American colonies and in the newly founded republic of the United States of America. People in the eastern part of the United States often relied upon Almanacs as a source of information and entertainment in an era when there was very little else to be had. In some homes, the Almanac might be found alongside the family bible, and it was often filled with homely philosophy and wisdom. |

| + | |||

| + | Banneker's fascination with mathematics and astronomy led him to calculate the positions of the sun and moon and other elements of a complete ephemeris for each of the years from 1791 to 1797. These predictions of planetary positions, as well as solar and lunar eclipses, were published within six yearly Almanacs printed and sold mainly in the middle Atlantic states from 1792 to 1797. He became known as the "Sable Astronomer" and contributed greatly to the movement for the freeing of slaves and granting of equal rights to people of color in the United States. | ||

| + | |||

| + | === Champion of civil rights and peace === | ||

| + | The emergence of several early Abolition Societies in Pennsylvania and Maryland coincided with Banneker's developments in promoting his almanac. The Christian abolitionists, many of them [[Quaker]]s, held the view that slavery is a dishonor to the Christian character. They argued for universal application of the principles stated in the preamble to the Constitution that rights come from God and that all men are created equal. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Banneker expressed a vision of social justice and equity that he wished to be adhered to in the everyday fabric of American life. He wrote to [[Thomas Jefferson]], the Secretary of State and author of the Declaration of Independence, a plea for justice for African Americans, calling on the colonists' personal experience as "slaves" of Britain and quoting Jefferson's own words. To support his plea, Banneker included a copy of his newly published ephemeris with its astronomical calculations. Jefferson replied to Banneker less than two weeks later in a series of statements asserting his own interest in the advancement of the equality of America's black population. Jefferson also forwarded a copy of Banneker's ''Almanac'' to the French Academy of Sciences in Paris. It was also used in Britain's House of Commons. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Following a life journey that would be echoed by others after him, including [[Martin Luther King Jr.]], and being largely supported by [[Caucasian]]s who promoted racial equality and an end to [[racism|racial discrimination]], Banneker spent the early years of his advocacy efforts arguing specifically for the rights of American blacks. In his later years, he turned to an argument for the peaceful equality of all humankind. In 1793, Banneker's Almanac included "A Plan for a Peace Office for the United States." The plan was formulated by Dr. Benjamin Rush and it included the idea of appointing a Secretary of Peace who would be responsible for establishing free schools where reading, writing, and arithmetic would be taught, as well as morals and the doctrines of religion. The plan went into great detail, painting a picture of universal brotherhood and peace on earth to be promoted through seven points including the building of a special wing on the federal hall where the business of the Secretary of Peace would be conducted (Bedini, 1999). | ||

== Benjamin Banneker Park and Memorial, Washington, DC == | == Benjamin Banneker Park and Memorial, Washington, DC == | ||

| − | A small [[urban park]] memorializing Benjamin Banneker is located at a prominent overlook (Banneker Circle) at the south end of L'Enfant Promenade in southwest Washington, D.C., a half [[mile]] south of the [[Smithsonian Institution|Smithsonian Institution's]] [[castle|"Castle"]] on the [[National Mall]]. | + | A small [[urban park]] memorializing Benjamin Banneker is located at a prominent overlook (Banneker Circle) at the south end of L'Enfant Promenade in southwest Washington, D.C., a half [[mile]] south of the [[Smithsonian Institution|Smithsonian Institution's]] [[castle|"Castle"]] on the [[National Mall]]. Although the [[National Park Service]] administers the park, the Government of the [[Washington, D.C.#Local government|District of Columbia]] owns the park's site. |

| − | + | == Letter to Thomas Jefferson on racism == | |

| − | |||

| − | Letter to Thomas Jefferson on | ||

"How pitiable it is that although you are so fully convinced of the goodness of the Father of mankind you should go against His will by detaining, by fraud and violence, so many of my brothers under groaning captivity and oppression; that you should at the same time be guilty of the most criminal act which you detest in others." | "How pitiable it is that although you are so fully convinced of the goodness of the Father of mankind you should go against His will by detaining, by fraud and violence, so many of my brothers under groaning captivity and oppression; that you should at the same time be guilty of the most criminal act which you detest in others." | ||

| Line 43: | Line 54: | ||

== Popular misconceptions == | == Popular misconceptions == | ||

| − | * Although he is said to be the first person who made the first clock in America and made the plans of Washington D.C this is denied in one of the only biographies of Banneker ''The Life Of Benjamin Banneker'' by Silvio Bedini. | + | * Although he is said to be the first person who made the first clock in America and made the plans of Washington D.C., this is denied in one of the only biographies of Banneker, ''The Life Of Benjamin Banneker'' by Silvio Bedini. Several watch and clockmakers were already established in the colony [Maryland] prior to the time that Banneker made his clock. In Annapolis alone there were at least four such craftsmen prior to 1750. Among these may be mentioned John Batterson, a watchmaker who moved to Annapolis in 1723; James Newberry, a watch and clockmaker who advertised in the Maryland Gazette on July 20, 1748; John Powell, a watch and clockmaker believed to have been indentured and to have been working in 1745; and Powell's master, William Roberts. Banneker's departure from the District of Columbia occurred at some time late in the month of April 1791. It was not until some ten months after Banneker's departure from the scene that L'Enfant was dismissed, by means of a letter from Jefferson dated February 27, 1792. This conclusively dispels any basis for the legend that after L'Enfant's dismissal and his refusal to make available his plan of the city, Banneker recollected the plan in detail from which Ellicott was able to reconstruct it. |

| − | * A popular [[urban legend]] erroneously describes Banneker's activities after he left the boundary survey. In 1792, President [[George Washington]] accepted the resignation of the [[France|French]]-American [[Pierre L'Enfant|Peter (Pierre) Charles L'Enfant]], who had drawn the first plans for the city of Washington but had quit out of frustration with his superiors. According to the legend, L'Enfant took his plans with him, leaving no copies behind. As the story is told, Banneker spent two days recreating the bulk of the city plans from memory. The plans that Banneker drew from his presumably photographic memory then provided the basis for the later construction of the federal capital city. However, the legend cannot be correct. President Washington and others, including Andrew Ellicott (who, after completing the boundary survey had begun a survey of the federal city in accordance with L'Enfant's plan), also possessed copies of various versions of the plan that L'Enfant had prepared, one of which L'Enfant had sent out for printing. | + | * A popular [[urban legend]] erroneously describes Banneker's activities after he left the boundary survey. In 1792, President [[George Washington]] accepted the resignation of the [[France|French]]-American [[Pierre L'Enfant|Peter (Pierre) Charles L'Enfant]], who had drawn the first plans for the city of Washington but had quit out of frustration with his superiors. According to the legend, L'Enfant took his plans with him, leaving no copies behind. As the story is told, Banneker spent two days recreating the bulk of the city plans from memory. The plans that Banneker drew from his presumably photographic memory then provided the basis for the later construction of the federal capital city. However, the legend cannot be correct. President Washington and others, including Andrew Ellicott (who, after completing the boundary survey had begun a survey of the federal city in accordance with L'Enfant's plan), also possessed copies of various versions of the plan that L'Enfant had prepared, one of which L'Enfant had sent out for printing. The U.S. [[Library of Congress]] presently owns a copy of a plan for the federal city that bears the adopted name of the plan's author, "Peter Charles L'Enfant". Further, Banneker left the federal capital area and returned to Ellicott Mills in early 1791, while L'Enfant was still refining his plans for the capital city as part of his federal employment (Bedini, 1999; Arnebeck, 1991). |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

| + | * Arnebeck, Bob. 1991. ''Through a Fiery Trial: Building Washington, 1790-1800''. Lanham, MD: Madison Books. ISBN 0819178322 | ||

| + | * Bedini, Silvio A. 1999. ''The Life of Benjamin Banneker, The First African American Man of Science,'' 2nd ed. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society. ISBN 0938420593 | ||

| + | * Tyson, Martha E. 1884. ''A Memoir of Benjamin Banneker, the Negro Astronomer''. Philadelphia: Friend's Book Association. {{OCLC|504797561}} | ||

| + | * Williams, George W. 1883. ''History of the Negro Race in America from 1619-1880''. 2 volumes. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons. | ||

| − | + | ==External links== | |

| − | + | All links retrieved September 27, 2023. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * [http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cocoon/legacies/MD/200003116.html Benjamin Banneker Historical Park & Museum]. | |

| − | *[http://lcweb2.loc.gov/cocoon/legacies/MD/200003116.html Benjamin Banneker Historical Park & Museum] | + | * [http://www.notablebiographies.com/Ba-Be/Banneker-Benjamin.html Benjamin Banneker Biography]. |

| − | + | * [http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Banneker.html Benjamin Banneker]. | |

| − | *[http://www.notablebiographies.com/Ba-Be/Banneker-Benjamin.html Benjamin Banneker | ||

| − | |||

| − | *[http:// | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Category:Physical sciences]] | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

| − | [[Category:Biographies of Scientists and | + | [[Category:Biographies of Scientists and Mathematicians]] |

[[Category:Biography]] | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|104096121}} | {{credit|104096121}} | ||

Latest revision as of 09:16, 27 September 2023

Benjamin Banneker, originally Banna Ka, or Bannakay (November 9, 1731 – October 9, 1806) was a free African American mathematician, astronomer, clockmaker, and publisher. He was America's first African American scientist and a champion of civil rights and world peace.

Life

Benjamin Banneker was born near Ellicot City, Maryland, on November 9, 1731. He was the first of three children to Robert, a freed slave from West Africa, and Mary Banneky, of English-African descent. Mary was the second of four daughters born to Molly Welsh, an English indentured servant who had earned her freedom by 1690. Molly rented a farm, raised corn and tobacco, and became a landowner. She purchased and freed two African slaves, one of whom (named Bannka or Banna Ka) she married. Bannka was the son of a Gambian king who was captured by slave traders in Africa. His name, derived from the Wolof dialect of the Senegal-Gambia region of West Africa, connoted a person of sweet or peaceful disposition (Bedini, 1999). This trait seems to have characterized his grandson's personality as well.

Benjamin Banneker learned to read and write from his grandmother, Molly, who encouraged him to practice reading from a large Bible she had ordered from England. He attended a one-room schoolhouse near his home, where he was instructed by a Quaker schoolmaster. Acquiring a thirst for knowledge, Banneker began to educate himself in mathematics and became intrigued by the solving of arithmetical puzzles. Given that few people of African descent in the colonies were not subject to some form of slavery, his situation was unusual and he eventually played a key role in the abolition movement.

Banneker's life and fortunes became linked with the Ellicots, a family of Quaker millers, who migrated from Pennsylvania to Maryland to pioneer the area known today as Ellicot City. The engineering methods and the mechanical workings of the grist mills built by the Ellicot brothers captured Banneker's interest. He soon began to associate with the Ellicots and found himself welcomed in gatherings and discussions at the Ellicot and Company Store. In time, he struck up a friendship with George Ellicot, a son of one of the original Ellicot brothers.

George shared Benjamin's fascination with natural science and mathematics and loaned him several important books, which Banneker used to learn about surveying and astronomy. The association with the Ellicots complemented his desire to learn new skills, and he was hired by Major Andrew Ellicot to assist in surveying the District of Columbia.

Retiring from that project due to health problems, the aging Banneker devoted his free time to the production of six almanacs, which included calculations of celestial phenomena for the years 1792-1797. These were published with the assistance of prominent abolitionists who saw in the talented astronomer a strong argument for the equality of all humans, regardless of race.

Benjamin Banneker died on October 9, 1806, at age 74, in his log cabin. He never married.

Accomplishments

Early years

In his early 20s, Banneker studied the detailed workings of a pocket watch. Such was his genius that he was able to fashion his own time piece, a mechanical clock, with carefully crafted wooden movements driven by a system of falling weights. Young Banneker became famous throughout the area. The clock continued to work, striking each hour, for more than 50 years.

At the age of 28, following his father Robert's death, Benjamin Banneker assumed ownership of the family farm and became responsible for his mother and sisters. He farmed tobacco, raised cows, and tended beehives, from which he derived much pleasure. At the age of 32, he acquired his first book, a bible, in which he inscribed the date of purchase, January 4, 1763 (Bedini, 1999).

The arrival of the Ellicot brothers, who established grist mills in the mid-Maryland region around the Patapsco River, marked a turning point in Banneker's life. His fascination with the construction and workings of the modern mechanical devices and the mills themselves led him to associate with the Ellicots. The latter were Quakers and staunch abolitionists who welcomed him into their circle. Banneker found himself welcomed at gatherings and discussions at the Ellicot and Company Store.

Eventually, Bannaker became friends with George Ellicot, one of the sons of the mill builders, who shared his interests in mathematics and astronomy. Young George loaned him several books, as well as a telescope, which greatly improved Banneker's grasp of astronomical and planetary phenomena. Thus, he began to calculate the appearances of solar and lunar eclipses and other celestial events. By 1790, he was able to calculate an ephemeris and attempted to have it published. At this point his work came to the attention of several prominent members of the newly emerging Abolitionist Movement in both Maryland and Pennsylvania.

Participation in Surveying of the District of Columbia

In early 1791, Joseph Ellicott's brother, Andrew Ellicot, hired Banneker to assist in a survey of the boundaries of the future 10 square-mile District of Columbia, which was to contain the federal capital city (the city of Washington) in the portion of the District that was northeast of the Potomac River. Because of illness and the difficulties in helping to survey, at the age of 59, an extensive area that was largely wilderness, Banneker left the boundary survey in April, 1791, and returned to his home at Ellicott Mills to work on his ephemeris.

Almanacs

Benjamin Banneker saw an opportunity to demonstrate what a person of African descent could achieve by publishing Almanacs in both Baltimore and Philadelphia. He had the support and encouragement of several prominent members of the Abolitionist Societies of both Pennsylvania and Maryland. Those who promoted the endeavor included Benjamin Franklin of Pennsylvania, Joseph Townsend of Harford County and Baltimore, Maryland, and Dr. Benjamin Rush, among others.

The yearly Almanac was a popular book during the eighteenth century in the American colonies and in the newly founded republic of the United States of America. People in the eastern part of the United States often relied upon Almanacs as a source of information and entertainment in an era when there was very little else to be had. In some homes, the Almanac might be found alongside the family bible, and it was often filled with homely philosophy and wisdom.

Banneker's fascination with mathematics and astronomy led him to calculate the positions of the sun and moon and other elements of a complete ephemeris for each of the years from 1791 to 1797. These predictions of planetary positions, as well as solar and lunar eclipses, were published within six yearly Almanacs printed and sold mainly in the middle Atlantic states from 1792 to 1797. He became known as the "Sable Astronomer" and contributed greatly to the movement for the freeing of slaves and granting of equal rights to people of color in the United States.

Champion of civil rights and peace

The emergence of several early Abolition Societies in Pennsylvania and Maryland coincided with Banneker's developments in promoting his almanac. The Christian abolitionists, many of them Quakers, held the view that slavery is a dishonor to the Christian character. They argued for universal application of the principles stated in the preamble to the Constitution that rights come from God and that all men are created equal.

Banneker expressed a vision of social justice and equity that he wished to be adhered to in the everyday fabric of American life. He wrote to Thomas Jefferson, the Secretary of State and author of the Declaration of Independence, a plea for justice for African Americans, calling on the colonists' personal experience as "slaves" of Britain and quoting Jefferson's own words. To support his plea, Banneker included a copy of his newly published ephemeris with its astronomical calculations. Jefferson replied to Banneker less than two weeks later in a series of statements asserting his own interest in the advancement of the equality of America's black population. Jefferson also forwarded a copy of Banneker's Almanac to the French Academy of Sciences in Paris. It was also used in Britain's House of Commons.

Following a life journey that would be echoed by others after him, including Martin Luther King Jr., and being largely supported by Caucasians who promoted racial equality and an end to racial discrimination, Banneker spent the early years of his advocacy efforts arguing specifically for the rights of American blacks. In his later years, he turned to an argument for the peaceful equality of all humankind. In 1793, Banneker's Almanac included "A Plan for a Peace Office for the United States." The plan was formulated by Dr. Benjamin Rush and it included the idea of appointing a Secretary of Peace who would be responsible for establishing free schools where reading, writing, and arithmetic would be taught, as well as morals and the doctrines of religion. The plan went into great detail, painting a picture of universal brotherhood and peace on earth to be promoted through seven points including the building of a special wing on the federal hall where the business of the Secretary of Peace would be conducted (Bedini, 1999).

Benjamin Banneker Park and Memorial, Washington, DC

A small urban park memorializing Benjamin Banneker is located at a prominent overlook (Banneker Circle) at the south end of L'Enfant Promenade in southwest Washington, D.C., a half mile south of the Smithsonian Institution's "Castle" on the National Mall. Although the National Park Service administers the park, the Government of the District of Columbia owns the park's site.

Letter to Thomas Jefferson on racism

"How pitiable it is that although you are so fully convinced of the goodness of the Father of mankind you should go against His will by detaining, by fraud and violence, so many of my brothers under groaning captivity and oppression; that you should at the same time be guilty of the most criminal act which you detest in others."

Popular misconceptions

- Although he is said to be the first person who made the first clock in America and made the plans of Washington D.C., this is denied in one of the only biographies of Banneker, The Life Of Benjamin Banneker by Silvio Bedini. Several watch and clockmakers were already established in the colony [Maryland] prior to the time that Banneker made his clock. In Annapolis alone there were at least four such craftsmen prior to 1750. Among these may be mentioned John Batterson, a watchmaker who moved to Annapolis in 1723; James Newberry, a watch and clockmaker who advertised in the Maryland Gazette on July 20, 1748; John Powell, a watch and clockmaker believed to have been indentured and to have been working in 1745; and Powell's master, William Roberts. Banneker's departure from the District of Columbia occurred at some time late in the month of April 1791. It was not until some ten months after Banneker's departure from the scene that L'Enfant was dismissed, by means of a letter from Jefferson dated February 27, 1792. This conclusively dispels any basis for the legend that after L'Enfant's dismissal and his refusal to make available his plan of the city, Banneker recollected the plan in detail from which Ellicott was able to reconstruct it.

- A popular urban legend erroneously describes Banneker's activities after he left the boundary survey. In 1792, President George Washington accepted the resignation of the French-American Peter (Pierre) Charles L'Enfant, who had drawn the first plans for the city of Washington but had quit out of frustration with his superiors. According to the legend, L'Enfant took his plans with him, leaving no copies behind. As the story is told, Banneker spent two days recreating the bulk of the city plans from memory. The plans that Banneker drew from his presumably photographic memory then provided the basis for the later construction of the federal capital city. However, the legend cannot be correct. President Washington and others, including Andrew Ellicott (who, after completing the boundary survey had begun a survey of the federal city in accordance with L'Enfant's plan), also possessed copies of various versions of the plan that L'Enfant had prepared, one of which L'Enfant had sent out for printing. The U.S. Library of Congress presently owns a copy of a plan for the federal city that bears the adopted name of the plan's author, "Peter Charles L'Enfant". Further, Banneker left the federal capital area and returned to Ellicott Mills in early 1791, while L'Enfant was still refining his plans for the capital city as part of his federal employment (Bedini, 1999; Arnebeck, 1991).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Arnebeck, Bob. 1991. Through a Fiery Trial: Building Washington, 1790-1800. Lanham, MD: Madison Books. ISBN 0819178322

- Bedini, Silvio A. 1999. The Life of Benjamin Banneker, The First African American Man of Science, 2nd ed. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society. ISBN 0938420593

- Tyson, Martha E. 1884. A Memoir of Benjamin Banneker, the Negro Astronomer. Philadelphia: Friend's Book Association. OCLC 504797561

- Williams, George W. 1883. History of the Negro Race in America from 1619-1880. 2 volumes. New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons.

External links

All links retrieved September 27, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.