Atlantis

Atlantis (Greek: Ἀτλαντὶς νῆσος, "Island of Atlas") is a mythical island nation first mentioned and described by the classical Greek philosopher Plato in the dialogues Timaeus and Critias. Alledged to be an imperical power in the ancient world before its downfall, the existence of Atlantis has been debated since Plato first spoke of it. The notion of Atlantis represents different ideas to everyone: for some, it is the ultimate archaeological site waiting to be discovered, a lost source of supernatural knowledge and power or perhaps nothing more than a philosophical treatise on the dangers of a civilization at the pinnacle of its power. Whether Atlantis did exist or is the creation of Plato may never be known, but until then the very idea of its existence will continue to inspire.

Origin

Plato's account of Atlantis, believed to be the first, is found in the dialogues Timaeus and Critias, written in the year 360B.C.E. In the socractic dialouge style, Plato conveys his story through a conversation among politicians Critias and Hermocrates as well as the philosophers Socrates and Timaeus. It is Critias who speaks of Atlantis, first in the Timaeus, describing briefly the vast empire "beyond the pillars of Hercules" that was defeated by Atheans after it attempted to conquer Europe and Asia Minor. In Timaeus Critias goes into more detail as he describes the civilization of Atlantis. Critias claims that his accounts of ancient Athens and Atlantis stem from a visit to Egypt by the Athenian lawgiver Solon in the sixth century B.C.E. In Egypt, Solon met a priest of Sais, who translated the history of ancient Athens and Atlantis, recorded on papyri in Egyptian hieroglyphs, into Greek.

According to Critias, the Hellenic gods of old divided the land so that each god might own a lot; Poseidon was appropriately, and to his liking, bequeathed the island of Atlantis. The island was larger than Libya and Asia Minor combined, but it afterwards was sunk by an earthquake and became an impassable mud shoal, inhibiting travel to any part of the ocean. The Egyptians described Atlantis as an island approximately 700 kilometres (435 mi) across, comprising mostly mountains in the northern portions and along the shore, and encompassing a great plain of an oblong shape in the south. Fifty stadia [about 600 km; 375 mi] inland from the coast was a mountain, where a native woman lived, with whom Poseidon fell in love and who bore him five pairs of male twins. The eldest of these, Atlas, was made rightful king of the entire island and the ocean (called the Atlantic Ocean in honor of Atlas), and was given the mountain of his birth and the surrounding area as his fiefdom. Atlas's twin Gadeirus or Eumelus in Greek, was given the extremity of the island towards the Pillars of Heracles. The other four pairs of twins — Ampheres and Evaemon, Mneseus and Autochthon, Elasippus and Mestor, and Azaes and Diaprepes were likewise given positions of power on the island. Poseidon carved the inland mountain where his love dwelt into a palace and enclosed it with three circular moats of increasing width, varying from one to three stadia and separated by rings of land proportional in size. The Atlanteans then built bridges northward from the mountain, making a route to the rest of the island. They dug a great canal to the sea, and alongside the bridges carved tunnels into the rings of rock so that ships could pass into the city around the mountain; they carved docks from the rock walls of the moats. Every passage to the city was guarded by gates and towers, and a wall surrounded each of the city's rings. The society of Atlantis lived peacefully at first, but as the society advanced, the desires of the islanders forced them to reach beyond the island's boundaries.

According to Critias, 9,000 years before his lifetime a war took place between those outside the Pillars of Hercules (generally thought to be the Strait of Gibraltar) and those who dwelt within them. The Atlanteans had conquered the parts of Libya within the columns of Heracles as far as Egypt and the European continent as far as Tyrrhenia, and subjected its people to slavery. The Athenians led an alliance of resistors against the Atlantean empire and as the alliance disintegrated, prevailed alone against the empire, liberating the occupied lands. "But later there occurred violent earthquakes and floods; and in a single day and night of misfortune all your warlike men in a body sank into the earth, and the island of Atlantis in like manner disappeared in the depths of the sea."

Fact or Fiction

The question of Atlantis' existence is one that as of late has been regulated to the category of New Age beliefs, yet it was not always like this. Admiration of Greek literaure and culture has been prevalent for centuries in Europe. While Atlantis was kept in circulation throughout the western world, along with the rest of Greek myth, but real interest in finding Atlantis did not become arosed until the 19th century. With Heinrich Schliemann's 1872 discovery of the lost city of Troy using.Some stories that started as myth have been proven to contain elements of truth, such as the story of Troy depicted by Homer in ''The Illiad'' and ''The Odessy'' which was considered legend until scholar discovered the actual city of Troy in Turkey. In the nineteenth century, many people, such as Ignatius Donnelly, began to do scholarly work on the idea of Atlantis as a not yet archaeological discovery. Along with scholarly works, more outlandish ideas attributing supernatural aspects to Atlantis became popular, such as those put forward by the theosophy movement. [1] On a side note, a new hypothesis states that this amount of time may have been "misinterpreted" by Solon. The Egyptians used a lunar calender based on months, and the Greeks a solar one based on years. It is therefore possible that the measure of time interpreted as 9,000 years may actually have been 9,000 months. This would place the destrucion of Atlantis within approximately 700 years beforehand, as there are 13 lunar months in a year. [2]

Symbolism

Plato scholar Dr Julia Annas[3] (Regents Professor of Philosophy, University of Arizona) has had this to say on the matter:

- The continuing industry of discovering Atlantis illustrates the dangers of reading Plato. For he is clearly using what has become a standard device of fiction — stressing the historicity of an event (and the discovery of hitherto unknown authorities) as an indication that what follows is fiction. The idea is that we should use the story to examine our ideas of government and power. We have missed the point if instead of thinking about these issues we go off exploring the sea bed. The continuing misunderstanding of Plato as historian here enables us to see why his distrust of imaginative writing is sometimes justified.[4]

Francis Bacon's 1627 novel The New Atlantis describes a utopian society, called Bensalem, located off the western coast of America. A character in the novel gives a history of Atlantis that is similar to Plato's, and places Atlantis in America. It is not clear whether Bacon means North or South America.

Many ancient philosophers viewed Atlantis as fiction, including (according to Strabo), Aristotle. However, in antiquity, there were also philosophers, geographers, and historians who believed that Atlantis was real.[5] For instance, the philosopher Crantor, a student of Plato's student Xenocrates, tried to find proof of Atlantis' existence. His work, a commentary on Plato's Timaeus, is lost, but another ancient historian, Proclus, reports that Crantor traveled to Egypt and actually found columns with the history of Atlantis written in hieroglyphic characters.[6] However, Plato did not write that Solon saw the Atlantis story on a column but on a source that can be "taken to hand".[7] Proclus' proof appears implausible.

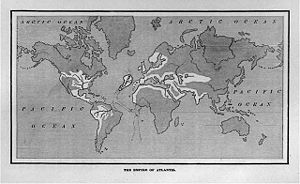

Location hypotheses

The 1882 publication of Atlantis: the Antediluvian World by Ignatius L. Donnelly stimulated much popular interest in Atlantis. Donnelly took Plato's account of Atlantis seriously and attempted to establish that all known ancient civilizations were descended from its high Neolithic culture. During the late 19th century, ideas about the legendary nature of Atlantis were combined with stories of other lost continents such as Mu and Lemuria by popular figures in the occult and the growing new age phenomenon. Helena Blavatsky, the "Grandmother of the New Age movement," writes in The Secret Doctrine that the Atlanteans were cultural heroes (contrary to Plato who describes them mainly as a military threat), and are the fourth "Root Race", succeeded by the "Aryan race". Rudolf Steiner wrote of the cultural evolution of Mu or Atlantis. Famed psychic Edgar Cayce first mentioned Atlantis in a life reading given in 1923,[8] and later gave its geographical location as the Caribbean, and proposed that Atlantis was an ancient, now-submerged, highly-evolved civilization which had ships and aircraft powered by a mysterious form of energy crystal. He also predicted that parts of Atlantis would rise in 1968 or 1969. The Bimini Road, found by Dr.J Manson Valentine, was a submarine geological formation just off North Bimini Island, discovered in 1968, has been claimed by some to be evidence of the lost civilization (among many other things) and is still being explored today.

Inside the Mediterranean

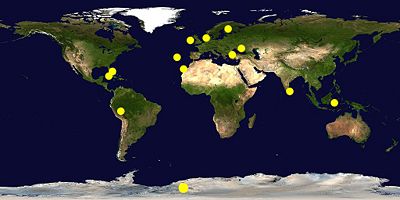

Since Donnelly's day, there have been dozens – perhaps hundreds – of locations proposed for Atlantis, to the point where the name has become a generic term rather than referring to one specific (possibly even genuine) location. This is reflected in the fact that many proposed sites are not within the Atlantic at all. Some are scholarly or archaeological hypotheses, while others have been made by psychic or other pseudoscientific means. Many of the proposed sites share some of the characteristics of the Atlantis story (water, catastrophic end, relevant time period), but none has been proven conclusively to be a true historical Atlantis. Most of the historically proposed locations are in or near the Mediterranean Sea, either islands such as Sardinia, Crete and Santorini, Cyprus, Malta, and Ponza or as land-based cities or states such as Troy, Tartessos or Tantalus (in the province of Manisa), Turkey, and the new theory of Israel-Sinai or Canaan as possible locations.[citation needed] The massive Thera eruption, dated either to the 17th or the 15th century B.C.E., caused a massive tsunami that experts hypothesise devastated the Minoan civilization on the nearby island of Crete, further leading some to believe that this may have been the catastrophe that inspired the story.

A. G. Galanopoulos argued that the time scale has been distorted by an error in translation, probably from Egyptian into Greek, which produced "thousands" instead of "hundreds"; this same error would rescale Plato's Kingdom of Atlantis to the size of Crete, while leaving the city the size of the crater on Thera. 900 years before Solon would be the 15th century B.C.E. [9]

Outside the Mediterranean

Locations as wide-ranging as Andalusia, Antarctica, Indonesia, underneath the Bermuda Triangle, and the Caribbean have been proposed as the true site of Atlantis. In the area of the Black Sea at least three locations have been proposed: Bosporus, Sinop and Ancomah (a legendary place near Trabzon). The nearby Sea of Azov was proposed as another site in 2003.[10] In Northern Europe, Sweden (by Olof Rudbeck in "Atland", 1672-1702), Ireland, and the North Sea have been proposed (the Swedish geographer Ulf Erlingsson combines the North Sea and Ireland in a comprehensive hypothesis).[citation needed] Areas in the Pacific and Indian Ocean have also been proposed including Indonesia, Malaysia or both (i.e. Sundaland) and stories of a lost continent off India named "Kumari Kandam" have drawn parallels to Atlantis.[citation needed] Even Cuba and the Bahamas have been suggested. Some believe that Atlantis stretched from the tip of Spain to Central America.[citation needed] According to Ignatius L. Donnelly in his book Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, there is a connection between Atlantis and Aztlan (the ancestral home of the Aztecs).[citation needed] He claims that the Aztecs pointed east to the Caribbean as the former location of Aztlan. Some have considered the Philippines to be the possible site of Atlantis, and proposed that the islands were remnants of Atlantis's mountains.

The Canary Islands have also been identified as a possible location, West of the Straits of Gibraltar but in close proximity to the Mediterranean Sea.[citation needed] Various islands or island groups in the Atlantic were also identified as possible locations, notably the Azores (Mid-Atlantic islands which are a territory of Portugal), and even several Caribbean islands.[citation needed] The submerged island of Spartel near the Strait of Gibraltar would coincide with some elements of Plato's account, matching both the location and the date of submersion given in the Critias. Popular culture increasingly places Atlantis in the Atlantic Ocean and perpetuates the original Platonic ideal.

In/Near the Mediterranean Sea

Many theories of Atlantis center around the Mediterranean. In part because of the Ancient Greek myth which is the first written record of Atlantis, but it was also a superhighway of transport in ancient times, allowing for trade and cultural exchange between emergent peoples of the region. The roots of Western civilization began in the Mesopotamia in nearby modern day Iraq. Some of the more popular theories include the Minoan civilization on Crete, the island of Sardinia as well as some other river valley civilizations.

Crete and Santorini

Among those who believe in an historical Atlantis, a common hypothesis holds that Plato's story of the destruction of Atlantis was inspired by massive volcanic eruptions on the Mediterranean island of Santorini during Minoan times. Skeptics of an Atlantic Ocean location usually promote this theory. Some consider this to be the likeliest hypothesis, though investigators (such as Frank Joseph) discount this theory as misleading. A main criticism of this hypothesis is that the ancient Greeks were well aware of volcanoes, and if there was a volcanic eruption, it would seem likely that it would be mentioned. Additionally, Pharaoh Amenhotep III commanded an emissary to visit the cities surrounding Crete and found the towns occupied shortly after the time Santorini was speculated to have completely destroyed the area.

Part of this hypothesis proposes, because Solon received his information from Egypt, that we assume that the Ancient Egyptian symbol for "hundred" was mistakenly read as "thousand". If this was possible, the translation would reduce the age and size of Atlantis by a factor of ten. This alteration would make Atlantis fit Minoan Crete well in size and age. Though, a translation error is believed by some to be unlikely because there is highly destinguishable variations in the visual appearance of hieroglyphic symbols of Egyptian numeric values.

Near Cape Spartel

Another recent hypothesis is based on a recreation of the geography of the Mediterranean at the time of Atlantis' supposed existence. Plato states that Atlantis was located beyond the Pillars of Hercules, the name given to the Strait of Gibraltar linking the Mediterranean to the Atlantic Ocean. 11,000 years ago the sea level in the area was some 130 metres lower, exposing a number of islands in the strait. One of these, Spartel, could have been Atlantis, though there are a number of inconsistencies with Plato's account.

Sardinia

In 2002 the Italian journalist Sergio Frau published a book, Le colonne d'Ercole ("Pillars of Hercules"), in which he states that before Eratosthenes, all the ancient Greek writers located the Pillars of Hercules on the Strait of Sicily, while only Alexander the Great's conquest of the east obliged Eratosthenes to move the pillars at Gibraltar in his description of the world.[11]

According to his thesis, the Atlantis described by Plato could be identified with Sardinia. In fact, a tsunami eradicated Sardinia which destroyed the enigmatic Nuragic civilization. The few survivors migrated to the nearby Italian peninsula, founding the Etruscan civilization, the basis for the later Roman civilization, while other survivors were part of those Sea Peoples that attacked Egypt.

Antarctica

The theory that Antarctica was Atlantis was particularly fashionable during the 1960s and 1970s, spurred on partly both by the isolation of the continent, H. P. Lovecraft's novella At the Mountains of Madness, and also the Piri Reis map, which purportedly shows Antarctica as it would be ice free, suggesting human knowledge of that period. Charles Berlitz, Erich Von Daniken and Peter Kolosimo have been amongst those popular authors who made this proposal.

Atlantis in art, literature and popular culture

The legend of Atlantis is featured in many books, movies, television series, games, songs, and other creative works. Recent examples of Atlantis on-screen include the television series Stargate Atlantis and the Disney animated movie Atlantis: The Lost Empire.

Pop Culture

Footnotes

- ↑ Carroll, Robert Todd (2005) ["Atlantis"] Retrieved April 18, 2007

- ↑ Hawk, Alex (1998) ["Atlantis.....Thira?"] Retrieved April 11, 2007

- ↑ http://www.u.arizona.edu/~jannas/, or for curriculum vitae: http://www.u.arizona.edu/~jannas/CVJAcurrent.htm

- ↑ J.Annas, Plato: A Very Short Introduction (OUP 2003), p.42 (emphasis not in the original)

- ↑ Nesselrath (2005), pp. 161-171.

- ↑ Proclus, In Tim. 1,76,1–2 (= FGrHist 665, F 31)

- ↑ Timaios 24a: τὰ γράμματα λαβόντες.

- ↑ Robinson, Lytle, 1972, Edgar Cayce’s Story of the Origin and Destiny of Man, Berkeley Books, New York, pg 51.

- ↑ Galanopoulos, Angelos Geōrgiou, and Edward Bacon, "Atlantis; the truth behind the legend". Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill; 1969

- ↑ http://establishment.com.ua/articles/2005/10/25/543/

- ↑ Frau, Sergio, Le colonne d'Ercole, NurNeon, ISBN 88-900740-0-0

Ancient sources

- Plato. 360 B.C.E. Timaeus, translated by Benjamin Jowett. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

- Plato. 360 B.C.E. Critias, translated by Benjamin Jowett. Retrieved April 12, 2007.

Modern sources

- Bichler, R (1986). 'Athen besiegt Atlantis. Eine Studie über den Ursprung der Staatsutopie', Canopus, vol. 20, no. 51, pp. 71-88.

- De Camp, LS (1954). Lost Continents: The Atlantis Theme in History, Science, and Literature, New York: Gnome Press.

- Donnelly, I (1882). Atlantis: The Antediluvian World, New York: Harper & Bros. Retrieved November 6, 2001, from Project Gutenberg.

- Ellis, R (1998). Imaging Atlantis, New York: Knopf. ISBN 0-679-44602-8

- Erlingsson, U (2004). Atlantis from a Geographer's Perspective: Mapping the Fairy Land, Miami: Lindorm. ISBN 0-9755946-0-5

- Flem-Ath, R & Wilson, C (2000). The Atlantis Blueprint, London: Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-85313-5

- Frau, S (2002). Le Colonne d'Ercole: Un'inchiesta, Rome: Nur neon. ISBN 88-900740-0-0

- Gill, C (1976). 'The origin of the Atlantis myth', Trivium, vol. 11, pp. 8-9.

- Görgemanns, H (2000). 'Wahrheit und Fiktion in Platons Atlantis-Erzählung', Hermes, vol. 128, pp. 405-420.

- Griffiths, JP (1985). 'Atlantis and Egypt', Historia, vol. 34, pp. 35f.

- Heidel, WA (1933). 'A suggestion concerning Platon's Atlantis', Daedalus, vol. 68, pp. 189-228.

- Jordan, P (1994). The Atlantis Syndrome, Stroud: Sutton Publishing. ISBN 0-7509-3518-9

- Martin, TH [1841] (1981). 'Dissertation sur l'Atlantide', in TH Martin, Études sur le Timée de Platon, Paris: Librairie philosophique J. Vrin, pp. 257-332.

- Morgan, KA (1998). 'Designer history: Plato's Atlantis story and fourth-century ideology', Journal of Hellenic Studies, vol. 118, pp. 101-118.

- Nesselrath, HG (1998). 'Theopomps Meropis und Platon: Nachahmung und Parodie', Göttinger Forum für Altertumswissenschaft, vol. 1, pp. 1-8.

- Nesselrath, HG (2001a). 'Atlantes und Atlantioi: Von Platon zu Dionysios Skytobrachion', Philologus, vol. 145, pp. 34-38.

- Nesselrath, HG (2001b). 'Atlantis auf ägyptischen Stelen? Der Philosoph Krantor als Epigraphiker', Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik, vol. 135, pp. 33-35.

- Nesselrath, HG (2002). Platon und die Erfindung von Atlantis, München/Leipzig: KG Saur Verlag. ISBN 3-598-77560-1

- Nesselrath, HG (2005). 'Where the Lord of the Sea Grants Passage to Sailors through the Deep-blue Mere no More: The Greeks and the Western Seas', Greece & Rome, vol. 52, pp. 153-171.

- Phillips, ED (1968). 'Historical Elements in the Myth of Atlantis', Euphrosyne, vol. 2, pp. 3-38.

- Ramage, ES (1978). Atlantis: Fact or Fiction?, Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-10482-3

- Settegast, M. (1987). Plato Prehistorian: 10,000 to 5000 B.C.E. in Myth and Archaeology, Cambridge, MA, Rotenberg Press.

- Spence, L [1926] (2003). The History of Atlantis, Mineola, NY: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-42710-2

- Szlezák, TA (1993). 'Atlantis und Troia, Platon und Homer: Bemerkungen zum Wahrheitsanspruch des Atlantis-Mythos', Studia Troica, vol. 3, pp. 233-237.

- Vidal-Naquet, P (1986). 'Athens and Atlantis: Structure and Meaning of a Platonic Myth', in P Vidal-Naquet, The Black Hunter, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 263-284. ISBN 0-8018-3251-9

- Wilson, C (1997). From Atlantis to the Sphinx, London: Virgin Books. ISBN 0-88064-176-2

- Zangger, E (1993). The Flood from Heaven: Deciphering the Atlantis legend, New York: William Morrow and Company. ISBN 0-688-11350-8

Further reading

- Gene Matlock, The last Atlantis book you’ll ever have to read: the Atlantis-Mexico-India connection. Tempe, AZ: Dandelion Books, 2001.

- Joseph, Frank, "The Destruction of Atlantis: Compelling Evidence of the Sudden Fall of the Legendary Civilization". Bear & Company, 2002. ISBN 1-879181-85-1

- Zangger, Eberhard, "''The Flood from Heaven: Deciphering the Atlantis legend". Sidgwick & Jackson, 1992, ISBN 0-688-11350-8.

- Mifsud, Anton, Simon Mifsud, Chris Agius Sultana, and Charles Savona Ventura, "Echoes of Plato's Island". (2nd edition) Malta, 2001. ISBN 99932-15-01-5

- Ashe, Geoffrey, "Atlantis : lost lands, ancient wisdom / Geoffrey Ashe". New York, N.Y., Thames and Hudson; 1992. ISBN 0-500-81039-7

- Zeilinga de Boer, Jelle, et. al., "Volcanoes in human history : the far-reaching effects of major eruptions". The Bronze Age eruption of Thera : destroyer of Atlantis and Minoan Crete?. Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press; 2002.

- Ley, Willy, "Another look at Atlantis, and fifteen other essays". Garden City, N.Y., Doubleday; 1969. LCCN 69011988

- Galanopoulos, Angelos Geōrgiou, and Edward Bacon, "Atlantis; the truth behind the legend". Indianapolis, Bobbs-Merrill; 1969. LCCN 71080738 //r892

- Donnelly, Ignatius L., "Atlantis: The Antediluvian World". New York, Harper, 1882. LCCN 06001749

- Erlingsson, Ulf, "Atlantis from a Geographer's Perspective: Mapping the Fairy Land". Lindorm Publishing, 2004. ISBN 0-9755946-0-5

- Flem-Ath, Rand & Wilson, Colin, The Atlantis Blueprint, 2000.

- Flem-Ath, Rand & Flem-Ath, Rose, When The Sky Fell.

- Shirley Andrews, Atlantis. Llewellyn Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-56718-023-X

- Charles Berlitz, The Bermuda Triangle

- Atlantis of the West: The Case For Britain's Drowned Megalithic Civilization, ISBN 0-7867-1145-0 , Paul Dunbavin

External links

- Atlantis: the Myth from Encyclopedia Mythica

General information

- The Atlantis Archives

- Atlantis Channel

- lost-civilizations.net

- about.com

- International Conference Atlantis 2005 , Milos/Greece

- [http://www.atlantis-scout.de/charter.htm Atlantis Research Charter about methods of Atlantis research

- Atlantis: Myth or Memory ? from UnXplained-Factor

Support a specific location

- Real Expedition Nov. 2006

- Atlantis in the Atlantic based on writings of Helena Blavatsky

- Antarctica was Atlantis

- Atlantis was in the Black Sea

- Atlantis was near Cyprus

- Bolivia was Atlantis

- Indonesia/Sundaland was Atlantis

- Atlantis was inspired by Silver Pit / Dogger Bank / Ireland / West Europe

- Atlantis Iberian-Mauretanian; the Acropolis before Gibraltar

- Israel was Atlantis (In Spanish)

- Tartessos was Atlantis

- Sea of Azov was Atlantis site

Support invention hypothesis

- Atlantis: No way, No how, No where" — Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal

- Skeptics dictionary

News

- PRWeb News, "Atlantis and Tartessus—Norway Scientific Institutions Recognize Spanish Paleographical Hypothesis". July 20, 2006.

- PRWeb News, "The Arab Authors Located to the Atlantis Island and the Amazonian Island in Andalusia". July 20, 2006.

- BBC News, "Tsunami clue to 'Atlantis' found". August 15, 2005.

- BBC News, "Satellite images 'show Atlantis' in Spain". June 6, 2004.

- BBC News, "Have scientists really found the lost city of Atlantis?". November 15, 2004.

- BBC News, "Atlantis 'obviously near Gibraltar'", September 20, 2001.

- Radford, Tim, The Guardian, "Evidence found of Noah's ark flood victims", September 14, 2000.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.