Difference between revisions of "Arapaho" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 120: | Line 120: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * Grinnell, George | + | *Grinnell, George Bird. ''The Cheyenne Indians: Their History and Lifeways Vol 1''. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, Inc., 2008. ISBN 978-1933316604 |

| − | + | *Hinz-Penner, Raylene. ''Searching for Sacred Ground: The Journey of Chief Lawrence Hart, Mennonite''. Telford, PA: Cascadia Publishing House, 2007. 978-1931038409 | |

| − | + | *Mann, Henrietta. ''Cheyenne-Arapaho Education 1871-1982''. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1997. ISBN 978-0870814624 | |

| − | + | *Moore, John L. ''The Cheyenne''. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 1996. ISBN 978-0631218623 | |

| − | * | + | * Waldman, Carl. ''Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes.'' New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744 |

| − | *John L. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * Waldman, Carl | ||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

Revision as of 21:43, 5 October 2011

| Arapaho |

|---|

| Total population |

| 5,000 |

| Regions with significant populations |

| United States (Colorado, Oklahoma, Wyoming) |

| Languages |

| English, Arapaho |

| Religions |

| Christianity, other |

| Related ethnic groups |

| Cheyenne and other Algonquian peoples |

The Arapaho (in French: Gens de Vache) tribe of Native Americans historically living on the eastern plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Sioux. Arapaho is an Algonquian language closely related to Gros Ventre, who are seen as an early offshoot of the Arapaho. Blackfoot and Cheyenne are the other Algonquian languages on the Plains, but are quite different from Arapaho. By the 1850s, Arapaho bands separated into two tribes: the Northern Arapaho and Southern Arapaho. The Northern Arapaho Nation has lived since 1878, with the Eastern Shoshone on the Wind River Reservation, the seventh largest reservation in the United States. The Southern Arapaho Tribe lives with the Southern Cheyenne in Oklahoma. Together their members are enrolled as a federally recognized tribe, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes.

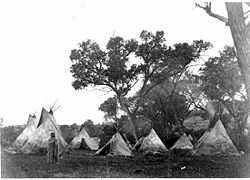

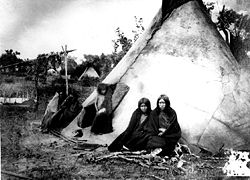

History

There is no direct historical or archaeological evidence to suggest how and when Arapaho bands entered the Plains culture area. The Arapaho Indian tribe most likely lived in Minnesota and North Dakota before entering the Plains. Before European expansion into the area, the Arapahos were living in South Dakota, Nebraska, Colorado, Wyoming, and Kansas. They lived in teepees which the women made from bison hide. Before they were sent to reservations, they migrated often chasing herds, so they had to design their teepees so that they could be transported easily. It is said that a whole village could pack up their homes and belongings and be ready to leave in only an hour. In winter the tribe split up into small camps sheltered in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains in present-day Colorado. In late spring they moved out onto the Plains into large camps to hunt buffalo gathering for the birthing season. In mid-summer Arapahos traveled into the Parks region of Colorado to hunt mountain herds, returning onto the Plains in late summer to autumn for ceremonies and for collective hunts of herds gathering for the rutting season.

They originally used dogs to pull travois with their belongings on them. When the Europeans came to North America, the Arapaho saw the Europeans' horses and realized that they could travel quicker and further with horses instead of dogs. They raided other Indian tribes, primarily the Pawnee and Comanche, to get the horses they needed.

Later on, they became great traders and often sold furs to other tribes and non-Indians. The name 'Arapaho' might have come from the Pawnee word for 'traders.'

The children often fished and hunted with their fathers for recreation. While they had more chores to do than present-day Arapaho, they still had time to play games. They played many games, including one involving a netted hoop and a pole where they would try to throw their pole through the center of the net. It was much like the game of darts which is enjoyed today.

Sand Creek Massacre

During November 1864, a small village of Cheyenne and Arapaho became the victims of a controversial attack by the Union Army, led by Colonel John Chivington. This attack is now known as the Sand Creek Massacre. According to an historical narrative on the Sand Creek Massacre titled "Chief Left Hand," by Margaret Coel, contributing factors that led to the Sand Creek Massacre were: Governor Evans' desire to hold title to the resource rich Denver-Boulder area; government trust officials' avoidance of Chief Left Hand (a linguistically gifted Southern Arapaho Chief), when executing a legal treaty that transferred title of the area away from Indian Trust; a local Cavalry stretched thin by the demands of the Civil War and the hijacking of their supplies by a few stray Indian warriors who had lost respect for their Chiefs; and followers of Chief Left Hand (including a group of Cheyenne and Arapaho elders, a few well behaved warriors, and mostly women and children), who had received a message to report to Fort Lyon with the promise of safety and food at the Fort, or risk being considered "hostile" and ordered killed by the Cavalry. (The tribe had been deprived of their normal wintering grounds in the Boulder area.)

Upon arrival at Fort Lyon, Chief Left Hand and his followers were accused of violence by Colonel Chivington who lusted to be a war hero. It must have been a conspiracy because Chief Left Hand and his people got the message that only those Indians that reported to Fort Lyon would be considered peaceful and all others would be considered hostile and ordered killed. Confused, Chief Left Hand and his followers turned away and traveled a safe distance away from the Fort to camp. A traitor gave Colonel Chivington directions to the camp. He and his battalion stalked and attacked the camp early the next morning. Rather than heroic, Colonel Chivington's efforts were considered a gross embarrassment to the Cavalry since he attacked peaceful elders, women and children. As a result of his war efforts, instead of the promotion he aspired for, he was relieved of his duties.

The late Eugene Ridgely, a Cheyenne-Northern Arapaho artist, is generally credited with bringing to light the fact that Arapahos were involved with the Massacre. His children Gail Ridgely, Benjamin Ridgley and, Eugene "Snowball" Ridgely were instrumental in designating the massacre site as a National Historic Site. In 1999 Benjamin Ridgley and Gail Ridgley organized a group of Northern Arapaho runners to run from Limon, Colorado to Ethete, Wyoming; in memory of their ancestors who were forced to run for their lives after being stalked by Colonel Chivington and his battalion. All of their efforts will be recognized and remembered by the "Sand Creek Massacre" signs that appear along the roadways from Limon, CO up through Casper, WY and over to Ethete, WY.

During November 1864, a small village of Cheyenne and Arapaho became the victims of a controversial attack by the Union Army, led by Colonel John Chivington. This attack is now known as the Sand Creek Massacre.

Chief Niwot or Left Hand (c. 1825-1864) was a tribal leader of the Arapahoe people and played an important part in the history of Colorado. His people lived along the Front Range often wintering in Boulder Valley, site of the future Boulder, Colorado. Despite breaching the borders of Arapahoe territory, early prospectors were welcomed by Niwot in Boulder Valley during the Colorado Gold Rush. Niwot died with many of his people at the hands of the Colorado Territory Militia in the Sand Creek Massacre. Throughout Boulder County, many places are attributed to him or his band of Araphoes. The town of Niwot, Colorado, Left Hand Canyon, Niwot Mountain, and Niwot Ridge are all named for him.

The late Eugene Ridgely, a Cheyenne-Northern Arapaho artist, is generally credited with bringing to light the fact that Arapahos were involved with the Massacre. His children, Eugene "Snowball" Ridgely, and Gail Ridgely, have been instrumental in designating the massacre site as a National Historic Site.

Language

The Arapaho language (also Arapahoe) is a Plains Algonquian language (an areal rather than genetic grouping) spoken almost entirely by elders in Wyoming. The language, which is in great danger of becoming extinct, has diverged very significantly phonologically from its posited proto-language, Proto-Algonquian.

Contemporary Arapaho

Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes are a united, federally recognized tribe of Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne people in western Oklahoma.

The Cheyennes and Arapahos are two distinct tribes with distinct histories. The Cheyenne (Tsis Tsis Tas/ The People) were once agrarian, or agricultural, people located near the Great Lakes in present-day Minnesota. Grinnell notes the Cheyenne language is a unique branch of the Algonquian language family and, The Nation itself, is descended from two related tribes, the Tsis Tsis Tas and the Suh' Tai. The latter is believed to have joined the Tsis Tsis Tas in the early 18th century (1: 1-2). The Tsis Tsis Tas and the Suh' Tai are characterized, and represented by two cultural heroes whom received divine articles which shaped the time-honored belief systems of the Southern and Northern families of the Cheyenne Nation. The Suh' Tai, represented by a man named Erect Horns, were blessed with the care of a sacred Buffalo Hat, which is kept among the Northern family. The Tsis Tsis Tas, represented by a man named Sweet Medicine, were bestowed with the care of a bundle of sacred Arrows, kept among the Southern Family. Inspired by Erect Horn's vision, they adopted the horse culture in the 18th century and moved westward onto the plains to follow the buffalo. The prophet Sweet Medicine organized the structure of Cheyenne society, including the Council of Forty-four peace chiefs and the warrior societies led by prominent warriors.[1]

The Arapaho, also Algonquian speaking, came from Saskatchewan, Montana, Wyoming, eastern Colorado, and western South Dakota in the 18th century. They adopted horse culture and became successful nomadic hunters. In 1800, the tribe began coalescing into northern and southern groups. Although the Arapaho had assisted the Cheyenne and Lakota in driving the Kiowa and Comanche south from the Northern Plains, in 1840 they made peace with both tribes. They became prosperous traders, until the expansion of American settlers onto their lands after the Civil War.[2]

The Cheyenne and Arapaho formed an alliance in the 18th and 19th centuries. Together they were a formidable military force, successful hunters, and active traders with other tribes. At the height of their alliance, their combined hunting territories spanned from Montana to Texas.[1]

The Arapaho signed the Fort Laramie Treaty with the US in 1851. It recognized and guaranteed their rights to traditional lands in portions of Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, and Wyoming. The US could not enforce the treaty, however, and European-American trespassers overran Indian lands. There were repeated conflicts between settlers and members of the tribes.

The US government brought the tribes to council again in 1867, to achieve peace under the Medicine Lodge Treaty. It promised the Arapaho a reservation in Kansas, but they disliked the location. They accepted a reservation with the Cheyenne in Indian Territory, so both tribes were forced to remove south near Fort Reno in present-day Oklahoma.[1]

The Dawes Act broke up the Cheyenne-Arapaho land base. All land not allotted to individual Indians was opened to settlement in the Land Run of 1892. The Curtis Act of 1898 dismantled the tribal governments in an attempt to have the tribal members assimilate to United States conventions and culture.

After the Oklahoma Indian Welfare Act passed in 1936, the Cheyenne and Arapaho organized a single tribal government in 1937.[2] The Indian Self-Determination Act of 1975 further enhanced tribal development.

The tribal government consists of the Tribal Council, Executive Branch, Legislative Branch, and Judicial Branch. The Tribal Council includes all tribal members over the age of 18.[3] The Executive Branch is led by the Governor and Lieutenant Governor. The Legislative Branch is made up of legislators from the four Arapaho districts and four Cheyenne districts. The Judicial Branch includes a Supreme Court, including one Chief Justice and four Associate Justices; a Trial Court, composed of one Chief Judge and at least one Associate Judge; and any lower courts deemed necessary by the Legislature.[4] In 2006 the tribes voted and ratified the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Constitution which replaced the 1975 constitution.[5]

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes are headquartered in Concho, Oklahoma.

The tribe operates three tribal smoke shops and four casinos: the Lucky Star Casino in Clinton, the Lucky Star Casino in Concho, the Feather Warrior Casino in Watonga, and the Feather Warrior Casino in Canton.[6] They also issue their own tribal vehicle tags. The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal Tribune is the tribe's newspaper.[6] The Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Culture and Heritage Program teaches hand games, powwow dancing and songs, horse care and riding, buffalo management, and Cheyenne and Arapaho language, and sponsored several running events.[7]

In partnership with Southwestern Oklahoma State University, the tribe founded the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College on August 25, 2006. Dr. Henrietta Mann, enrolled tribal member, currently is president. The campus is in Weatherford, Oklahoma and the school offers programs in Tribal Administration, American Indian Studies, and General Studies.[8]

Casinos

In July of 2005, Arapahos won a contentious court battle with the State of Wyoming to get into the gaming or casino industry. The 10th Circuit Court ruled that the State of Wyoming was acting in bad faith when it would not negotiate with the Arapahos for gaming. Presently, the Arapaho Tribe owns and operates high-stakes, Class III gaming at the Wind River Casino, Little Wind Casino and 789 Smoke Shop & Casino. They are regulated by a Gaming Commission composed of three Tribal members. The Northern Arapaho Tribe opened the first casinos in Wyoming.

Meanwhile, the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes operate three casinos: the Lucky Star Casino in Clinton, the Feather Warrior Casino in Watonga, and the Feather Warrior Casino in Canton.[6]

Wind River Indian Reservation

Wind River Indian Reservation is an Indian reservation shared by the Eastern Shoshone and Northern Arapaho tribes of Native Americans in the central western portion of the U.S. state of Wyoming. It is the seventh-largest Indian reservation by area in the United States, encompassing a land area of 8,995.733 km² (3,473.272 sq mi), encompassing most of Fremont County [9]. The reservation is surrounded by the Wind River Mountain Range, Owl Creek Mountains, and the Absaroka Mountains. The 2000 census reported a population of 23,250 inhabitants.[10] The largest town is Riverton. Headquarters are at Fort Washakie. Also home to the Wind River Casino, Little Wind Casino, 789 Smoke Shop & Casino (All Northern Arapahoe) and Shoshone Rose Casino (Eastern Shoshone), which are the only casinos in Wyoming.

The Wind River Indian Reservation was established for the Eastern Shoshone Indians in 1868. Camp Auger, a military post with troops was established at the present site of Lander on June 28, 1869. In 1870 the name was changed to Camp Brown and in 1871 the post was moved to the current site of Fort Washakie. The nickname was changed to honor the Shoshone Chief Washakie in 1878 and continued to serve as a military post until its abandonment in 1909.[11] A government school and hospital functioned for many years east of Fort Washakie and children were sent here to board during the school year. St. Michael's at Ethete was constructed in 1917-20. The village of Arapahoe was originally established as a sub-agency to distribute rations to the Arapaho and at one time had a large trading post. In 1906 a portion of the reservation was ceded to white settlement and Riverton evolved on some of this land. Lands were allotted in the 1800's to the various families and names were anglicized. Irrigation was brought in to develop farming and ranching and a flour mill constructed near Fort Washakie.[12]

Of the population in 2000, 6,728 (28,9%) were Native Americans (full or part) and of them 54% were Arapaho and 30% Shoshone.[10] Of the Native American population, 22% spoke a language other than English at home.

Literary reference

In Centennial, James A. Michener's epic historical novel about the West from prehistoric to modern times, the fourth chapter is about the Arapahoe peoples and their customs.

Notable Arapahos

- Chief Little Raven (ca. 1810-1889), negotiated peace between the Southern Arapaho and Cheyenne and the Comanche, Kiowa, and Plains Apache. He secured rights to the Cheyenne-Arapaho Reservation in Indian Territory.[13]

- Chief Niwot (Left Hand) (ca. 1840-1911), celebrated warrior and advocate for Arapahos in Washington D.C. He brought the Ghost Dance to the tribe and served as Principal Chief.[14]

- Chief Niwot (ca. 1825-1864), led a band in Northern Colorado and died from wounds sustained during the Sand Creek Massacre).

- Sherman Coolidge (Runs-on-Top) (1862–1932), Episcopal minister and educator, nominated as a "Wyoming Citizen of the Century." [15]

- Carl Sweezy (1881–1953), early professional Native American fine artist

- Mirac Creepingbear (1947–1990), Arapaho-Kiowa painter

- Harvey Pratt (b. 1941), contemporary Cheyenne-Arapaho artist

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Moore, John H. Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. (retrieved 7 Feb 2009)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Fowler, Loretta. Arapaho, Southern., Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture, retrieved 7 Feb 2009

- ↑ Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes Constitution, Article V, Section 1

- ↑ Cheyenne-Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Constitution and Bylaws. 1975 (retrieved 7 Feb 2009)

- ↑ http://www.c-a-tribes.org/cheyenne-arapaho-tribes-constitution

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. 2007 (retrieved 7 Feb 2009) Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "ca" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Culture. Cheyenne & Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma. 2007 (retrieved 7 Feb 2009)

- ↑ General Information. Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College. (retrieved 2 Nov 2009)

- ↑ Background of Wind River Reservation

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 2000 Census, U.S. Census Bureau

- ↑ Eastern Shoshone Tribal Culture

- ↑ Eastern Shoshone Tribal Culture

- ↑ May, Jon D. Little Raven (ca. 1810-1889). Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. (retrieved 7 February 2009)

- ↑ May, Jon D. Left Hand (ca. 1840-1911). Oklahoma Historical Society's Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History & Culture. (retrieved 7 February 2009)

- ↑ Wyoming Citizen of the Century Nominee Sherman Coolidge. University of Wyoming American Heritage Center. Retrieved 7 November 2009.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Grinnell, George Bird. The Cheyenne Indians: Their History and Lifeways Vol 1. Bloomington, IN: World Wisdom, Inc., 2008. ISBN 978-1933316604

- Hinz-Penner, Raylene. Searching for Sacred Ground: The Journey of Chief Lawrence Hart, Mennonite. Telford, PA: Cascadia Publishing House, 2007. 978-1931038409

- Mann, Henrietta. Cheyenne-Arapaho Education 1871-1982. Boulder, CO: University Press of Colorado, 1997. ISBN 978-0870814624

- Moore, John L. The Cheyenne. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley-Blackwell, 1996. ISBN 978-0631218623

- Waldman, Carl. Encyclopedia of Native American Tribes. New York, NY: Checkmark Books, 2006. ISBN 978-0816062744

External links

- The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes, official website

- Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes of Oklahoma Constitution and By-Laws

- Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribal College

- Northern Arapaho Tribe

| ||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.