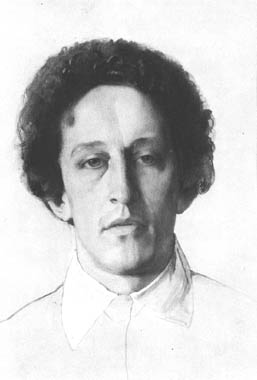

Alexander Blok

Alexander Blok (Александр Александрович Блок, November 16, 1880 - August 7, 1921), was perhaps the most gifted lyrical poet produced by Russia after Alexander Pushkin.[1]

Early Life and Influences

Blok was born in St Petersburg, into a sophisticated and intellectual family. Some of his relatives were men of letters, his father being a law professor in Warsaw, and his maternal grandfather the rector of the Saint Petersburg University. After his parents' separation, Blok lived with aristocratic relatives at the Shakhmatovo manor near Moscow, where he discovered the philosophy of his uncle Vladimir Solovyov, and the verse of then-obscure 19th-century poets, Fyodor Tyutchev and Afanasy Fet. These influences would be fused and transformed into the harmonies of his early pieces, later collected in the book Ante Lucem.

He fell in love with Lyubov (Lyuba) Mendeleeva (the great chemist's daughter) and married her in 1903. Later, she would involve him in a complicated love-hate relationship with his fellow Symbolist Andrey Bely. To Lyuba he dedicated a cycle of poetry that brought him fame, Stikhi o prekrasnoi Dame (Verses About the Beautiful Lady, 1904). In it, he transformed his humble wife into a timeless vision of the feminine soul and eternal womanhood (The Greek Sophia of Solovyov's teaching).

Blok's Early Poetry

The idealized mystical images present in his first book helped establish Blok as a leader of the Russian Symbolist movement. Blok's early verse is impeccably musical and rich in sound, but he later sought to introduce daring rhythmic patterns and uneven beats into his poetry. Poetical inspiration came to him naturally, often producing unforgettable, otherwordly images out of the most banal surroundings and trivial events (Fabrika, 1903). Consequently, his mature poems are often based on the conflict between the Platonic vision of ideal beauty and the disappointing reality of foul industrial outskirts (Neznakomka, 1906).

The image of St Petersburg he crafted for his next collection of poems, The City (1904-08), was both impressionistic and eerie. Subsequent collections, Faina and the Mask of Snow, helped augment Blok's reputation to fabulous dimensions. He was often compared with Alexander Pushkin, and the whole Silver Age of Russian Poetry was sometimes styled the "Age of Blok". In the 1910s, Blok was almost universally admired by literary colleagues, and his influence on younger poets was virtually unsurpassed. Anna Akhmatova, Marina Tsvetaeva, Boris Pasternak, and Vladimir Nabokov wrote important verse tributes to Blok.

Revolution in Rhythm and Subject Matter

During the later period of his life, Blok concentrated primarily on political themes, pondering the messianic destiny of his country (Vozmezdie, 1910-21; Rodina, 1907-16; Skify, 1918). Influenced by Solovyov's doctrines, he was full of vague apocalyptic apprehensions and often vacillated between hope and despair. "I feel that a great event was coming, but what it was exactly was not revealed to me", he wrote in his diary during the the summer of 1917. Quite unexpectedly for most of his admirers, he accepted the October Revolution as the final resolution of these apocalyptic yearnings.

Blok expressed his views on the revolution in the enigmatic The Twelve (1918). The long poem, with its "mood-creating sounds, polyphonic rhythms, and harsh, slangy language" (as the Encyclopædia Britannica termed it), is one of the most controversial in the whole corpus of the Russian poetry. It describes the march of twelve Bolshevik rapists and murderers (likened to the Twelve Apostles who followed Christ) through the streets of revolutionary Petrograd, with a fierce winter blizzard raging around them.

The Twelve promptly alienated Blok from a mass of his intellectual followers (who accused him of appallingly bad taste), while the Bolsheviks scorned his former mysticism and aesceticism. He slid into a state of depression and withdrew from the public eye. The true cause of Blok's death at the age of 40 is still disputed. Some say that he died from the famine caused by the Russian Civil War. Others still attribute his death to what they ambiguously call a "lack of air." Several months earlier, Blok had delivered a celebrated lecture on Pushkin, whom he believed to be an iconic figure capable of uniting White and Red Russia.

Symbolism of Alexander Blok

Alexander Blok, on all accounts one of the most important poets of the century, envisioned his poetical output as composed of three volumes. The first volume contains his early poems about the Fair Lady; its dominant colour is white. The second volume, dominated by the blue colour, comments upon impossibility to rich the ideal he craved for. The third volume, featuring his poems from pre-revolutionary years, is steeped in fiery or bloody red.

In Blok's poetry, colours are essential, for they convey mystical intimations of things beyond human experience. Blue or violet is the colour of frustration, when the poet understands that his hope to see the Lady is delusive. The yellow colour of street lanterns, windows and sunsets is the colour of treason and triviality. Black hints at something terrible, dangerous but potentially capable of esoteric revelation. Russian words for yellow and black are spelled by the poet with a long O instead of YO, in order to underline "a hole inside the word".

Following on the footsteps of Fyodor Tyutchev, Blok developed a complicated system of poetic symbols. In his early work, for instance, wind stands for the Fair Lady's approach, whereas morning or spring is the time when their meeting is most likely to happen. Winter and night are the evil times when the poet and his lady are far away from each other. Bog and mire stand for everyday life with no spiritual light from above.

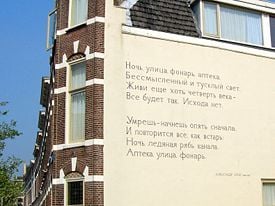

"Night, street, lamp, drugstore" (1912)

|

Night, street, lamp, drugstore, |

Ночь, улица, фонарь, аптека, |

(Written on October 10, 1912. source: [1])

Notes

- ↑ Encyclopaedia Britannica, 15th edition, 2006. Article "Russia".

External links

- Alice Koonen reading Blok's poem

- Leon Trotsky's article on Alexander Blok

- In Defense of A. Blok by Nikolai Berdyaev

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.