Difference between revisions of "Aging" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (36 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} | |

[[File:Old woman with young baby boy.JPG|thumb|right|300px|95-year-old woman holding a five-month-old boy]] | [[File:Old woman with young baby boy.JPG|thumb|right|300px|95-year-old woman holding a five-month-old boy]] | ||

| − | '''Aging''' or '''ageing''' | + | '''Aging''' or '''ageing''' is the process of becoming older. The term refers especially to [[human]]s, many other [[animal]]s, and [[fungi]]. In the broader sense, aging can refer to single cells within an [[organism]] which have ceased dividing ([[cellular senescence]]) or to the population of a species ([[population aging]]). |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | This article focuses primarily on humans. Aging represents the accumulation of changes in a [[human being]] over time and can encompass [[Human body|physical]], [[psychological]], and social changes. Reaction time, for example, may slow with age, while memories and general knowledge typically increase. Society's view of aging, for example valuing youth over experience, affects a person's self-perception of their own aging. A belief in an [[afterlife]], the continued existence of an eternal [[spirit]] or [[soul]] after the [[death]] of the physical body, gives a different view to aging and reduces the stress associated with physical deterioration. | ||

| − | + | == Definitions == | |

| + | Biological aging refers to an [[organism]]'s increased rate of death as it progresses through its lifecycle and increases its chronological age.<ref name=McDonald>Roger B. McDonald, ''Biology of Aging'' (Garland Science, 2019, ISBN 0815345674).</ref> Another possible way to define aging is through functional definitions, of which there are two main types: The first describes how varying types of deteriorative changes that accumulate in the life of a post-maturation organism can leave it vulnerable, leading to a decreased ability of the organism to survive: "Aging is the progressive accumulation of changes with time that are associated with or responsible for the ever-increasing susceptibility to disease and death which accompanies advancing age."<ref>D. Harman, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC349208/ The aging process] ''Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A'' 78(11) (November 1981): 7124–7128. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> The second is a senescence-based definition which describes age-related changes in an organism that increase its mortality rate over time by negatively affecting its vitality and functional performance.<ref name=McDonald/> | ||

| + | {{readout||right|250px|Aging is the natural biological process that all [[animal]] life, including [[human being]]s, go through from conception to [[death]]}} | ||

| + | An important distinction to make is that biological aging is not the same as the accumulation of [[disease]]s related to old age; ''disease'' is a blanket term used to describe a process within an organism that causes a decrease in its functional ability.<ref name=McDonald/> Aging is the natural and inevitable biological process that all [[animal]] life, including [[human being]]s, go through from conception through birth to [[death]]. While death by other external causes, such as disease, accident, predation, and so forth, is common, nonetheless death would occur naturally due to aging even in the absence of such causes. | ||

| + | |||

| + | == Biological basis == | ||

| + | The causes of aging are uncertain, but appear to involve a number of factors.<ref>Stefan I. Liochev, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4712935/ Which Is the Most Significant Cause of Aging?] ''Antioxidants (Basel)'' 4(4) (December 2015): 793–810. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> The factors proposed to influence biological aging fall into two main categories: ''programmed'' and ''damage-related''. They are not necessarily mutually exclusive. | ||

| + | The first posits that aging is programmed and therefore follows an inexorable path, a biological timetable, perhaps one that might be a continuation of that which regulates childhood growth and development. This regulation would depend on changes in [[gene]] expression that affect the systems responsible for maintenance, repair, and defense responses. Programmed aging should not be confused with programmed cell death ([[apoptosis]]). | ||

| − | + | The second category of theories suggests various sources and targets of damage that lead to aging. Damage-related factors include internal and environmental assaults to living organisms that induce cumulative damage at various levels. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | A third, novel concept is that aging is mediated by [[Virtuous circle and vicious circle|vicious cycles]].<ref>Aleksey V. Belikov, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30458244/ Age-related diseases as vicious cycles] ''Ageing Research Reviews'' 49 (January 2019): 11–26. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | + | Additionally, there can be other reasons which can speed up the rate of aging in organisms including human beings, such as obesity and compromised [[immune system]]. | |

| − | |||

| + | ===Programmed factors=== | ||

| + | The programmed approach suggests three major mechanisms which control aging:<ref name=Jin>Kunlin Jin, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2995895/ Modern Biological Theories of Aging] ''Aging Dis.'' 1(2) (October 2010): 72–74. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> | ||

| + | ;Programmed Longevity | ||

| + | Aging is the result of a sequential switching on and off of certain [[gene]]s, with senescence being defined as the time when age-associated deficits are manifested. | ||

| + | ;Endocrine Theory | ||

| + | Biological clocks act through [[hormone]]s to control the pace of aging. | ||

| + | ;Immunological Theory | ||

| + | The [[immune system]] is programmed to decline over time, which leads to an increased vulnerability to infectious [[disease]]s and thus aging and death. | ||

| + | The rate of aging varies substantially across different species, and this, to a large extent, is genetically based. For example, numerous [[perennial plant]]s ranging from [[strawberry|strawberries]] and [[potato]]es to [[willow]] trees typically produce [[clone]]s of themselves by [[vegetative reproduction]] and are thus potentially immortal, while [[annual plants]] such as [[wheat]] and [[watermelon]]s die each year and reproduce by sexual reproduction. The oldest [[animal]]s known so far are 15,000-year-old [[Antarctica|Antarctic]] [[sponge]]s,<ref>Marnie Chesterton, [https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-40224991 The oldest living thing on Earth] ''BBC News'', June 12, 2017. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> which can reproduce both sexually and clonally. | ||

| − | + | Clonal immortality apart, there are certain species whose individual lifespans stand out among Earth's life-forms, including the [[bristlecone pine]] at around 5,000 years<ref>[http://www.rmtrr.org/oldlist.htm Oldlist] ''Rocky Mountain Tree Ring Research''. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> invertebrates like the [[hard clam]] (known as ''quahog'' in New England) at 508 years,<ref>Danuta Sosnowska, Chris Richardson, William E. Sonntag, Anna Csiszar, Zoltan Ungvari, and Iain Ridgway, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4271020/ A heart that beats for 500 years] ''The Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences'' 69(12) (December 2014): 1448–1461. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> the [[Greenland shark]] at 400 years,<ref>J. Nielsen, ''et al'', [https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:6c040460-9519-4720-9669-9911bdd03b09 Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus)] ''Science'' 353(6300) (August 2016): 702–704. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> various deep-sea [[tube worms]] at over 300 years,<ref>Alanna Durkin, Charles R. Fisher, Erik E. Cordes, [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00114-017-1479-z Extreme longevity in a deep-sea vestimentiferan tubeworm and its implications for the evolution of life history strategies] ''The Science of Nature'' 104(7–8) (August 2017): 63. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> and [[lobster]]s.<ref>Jacob Silverman, [https://animals.howstuffworks.com/marine-life/400-pound-lobster.htm Is there a 400 pound lobster out there?] ''How Stuff Works''. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> Such organisms are sometimes said to exhibit [[negligible senescence]].<ref>John C. Guerin, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15247078/ Emerging area of aging research: long-lived animals with "negligible senescence"] ''Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences'' 1019(1) (June 2004): 518–520. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | [[File:Habibaadansalat.jpg|thumb|right|350px|An elderly [[Somali people|Somali]] woman]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Damage-related factors=== | |

| − | + | Numerous damage-related factors have been proposed that lead to aging, including the following:<ref name=Jin/> | |

| − | + | ;Wear and tear theory | |

| − | + | Cells and tissues have vital parts that wear out resulting in aging. Like components of an aging machine, parts of the body eventually wear out from repeated use, leading to cell death and inability to function. | |

| − | + | ;Rate of living theory | |

| + | This suggests that the greater an organism’s rate of [[oxygen]] basal [[metabolism]], the shorter its life span. While helpful, this does not explain maximum life span. | ||

| − | + | ;Cross-linking theory | |

| − | + | According to this theory, an accumulation of cross-linked [[protein]]s damages cells and tissues, slowing down bodily processes and resulting in aging. | |

| − | + | ;Free radical theory | |

| + | This proposes that [[free radical]]s cause damage to the macromolecular components of the cell, giving rise to accumulated damage causing cells, and eventually organs, to stop functioning. Macromolecules, such as [[nucleic acid]]s, [[lipid]]s, [[sugar]]s, and [[proteins]], are susceptible to free radical attack. [[Enzyme]]s, which are natural antioxidants, are found in the body and function to curb build-up of free radicals. | ||

| − | + | ;Somatic DNA damage theory | |

| − | + | [[DNA]] damage occurs continuously in cells of living organisms. While most of the damage is repaired naturally, some accumulates as the repair mechanisms cannot correct defects as fast as they are produced. Thus, aging results from damage to the genetic integrity of the body’s cells. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Other suggested factors include: progressive loss of physiological integrity through genomic instability (mutations accumulated in nuclear DNA, in mtDNA, and in the nuclear lamina) and [[telomere]] attrition.<ref>Carlos López-Otín, Maria A. Blasco, Linda Partridge, Manuel Serrano, and Guido Kroemer, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3836174/ The Hallmarks of Aging] ''Cell'' 153(6) (June 2013): 1194–1217. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> Also, accumulation of waste products in cells presumably interferes with [[metabolism]]. For example, a waste product called [[lipofuscin]] is formed by a complex reaction in cells that binds fat to proteins. This waste accumulates in the cells as small granules, which increase in size as a person ages.<ref> Edward J. Masoro and Steven N. Austad (eds.), ''Handbook of the Biology of Aging'' (Academic Press, 2006, ISBN 0120883872).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Effects == | == Effects == | ||

| − | [[File:Senescence.JPG|thumb|300px|Enlarged ears and noses of old humans are sometimes blamed on continual cartilage growth, but the cause is more probably gravity.<ref>Stephen Moss, [https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/shortcuts/2013/jul/17/big-ears-grow-as-we-age Big ears: they really do grow as we age] ''The Guardian'', July 17, 2013. Retrieved | + | [[File:Senescence.JPG|thumb|300px|Enlarged ears and noses of old humans are sometimes blamed on continual cartilage growth, but the cause is more probably gravity.<ref>Stephen Moss, [https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/shortcuts/2013/jul/17/big-ears-grow-as-we-age Big ears: they really do grow as we age] ''The Guardian'', July 17, 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref>]] |

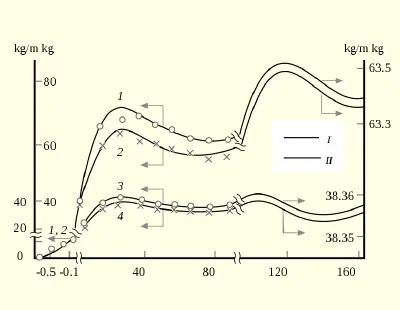

| − | [[File: Age dynamics of the body mass.png|thumb|400px|Age dynamics of the body mass (1, 2) and mass normalized to height (3, 4) of men (1, 3) and women (2, 4).<ref name="Age dynamics">I. G. Gerasimov and Dmitry Yu Ignatov, [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226729610_Age_Dynamics_of_Body_Mass_and_Human_Lifespan Age Dynamics of Body Mass and Human Lifespan] ''Journal of Evolutionary Biochemistry and Physiology'' 40(3) (2004):343–349. Retrieved | + | [[File: Age dynamics of the body mass.png|thumb|400px|Age dynamics of the body mass (1, 2) and mass normalized to height (3, 4) of men (1, 3) and women (2, 4).<ref name="Age dynamics">I. G. Gerasimov and Dmitry Yu Ignatov, [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226729610_Age_Dynamics_of_Body_Mass_and_Human_Lifespan Age Dynamics of Body Mass and Human Lifespan] ''Journal of Evolutionary Biochemistry and Physiology'' 40(3) (2004):343–349. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref>]] |

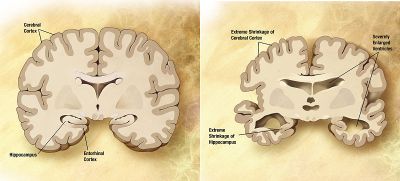

[[File:Alzheimer's disease brain comparison.jpg|thumb|400px|Comparison of a normal aged brain (left) and a brain affected by [[Alzheimer's disease]] (right).]] | [[File:Alzheimer's disease brain comparison.jpg|thumb|400px|Comparison of a normal aged brain (left) and a brain affected by [[Alzheimer's disease]] (right).]] | ||

| − | Aging increases the [[risk factor|risk]] of [[disease]]s. | + | In humans, aging represents the accumulation of changes in a [[human being]] over time and can encompass [[Human body|physical]], [[psychological]], and social changes. Reaction time, for example, may slow with age, while memories and general knowledge typically increase. Aging also increases the [[risk factor|risk]] of [[disease]]s. |

A number of characteristic aging symptoms are experienced by a significant proportion of human beings during their lifetimes, including the following: | A number of characteristic aging symptoms are experienced by a significant proportion of human beings during their lifetimes, including the following: | ||

| − | * After peaking in the mid-20s, female [[fertility]] declines.<ref>[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK293711/ Infertility: Overview] ''Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care'', March 25, 2015. Retrieved | + | * After peaking in the mid-20s, female [[fertility]] declines.<ref>[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK293711/ Infertility: Overview] ''Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care'', March 25, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

* After age 30 the mass of human body is decreased until 70 years and then shows damping oscillations.<ref name="Age dynamics"/> | * After age 30 the mass of human body is decreased until 70 years and then shows damping oscillations.<ref name="Age dynamics"/> | ||

| − | * Muscles have reduced capacity of responding to exercise or injury and loss of muscle mass and strength ([[sarcopenia]]) is common.<ref>James G. Ryall, Jonathan D. Schertzer, and Gordon S. Lynch, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18299960/ Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and weakness] ''Biogerontology'' 9(4) (August 2008): 213–228. Retrieved | + | * Muscles have reduced capacity of responding to exercise or injury and loss of muscle mass and strength ([[sarcopenia]]) is common.<ref>James G. Ryall, Jonathan D. Schertzer, and Gordon S. Lynch, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18299960/ Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and weakness] ''Biogerontology'' 9(4) (August 2008): 213–228. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> |

| − | *Hand strength and mobility are decreased during the aging process. These things include "hand and finger strength and ability to control submaximal pinch force and maintain a steady precision pinch posture, manual speed, and hand sensation."<ref>Vinoth K. Ranganathan, Vlodek Siemionow, Vinod Sahgal, and Guang H. Yue, [https://agsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911240.x Effects of Aging on Hand Function] ''Journal of the American Geriatrics Society'' 49(11) (November 2001):1478–1484. Retrieved | + | *Hand strength and mobility are decreased during the aging process. These things include "hand and finger strength and ability to control submaximal pinch force and maintain a steady precision pinch posture, manual speed, and hand sensation."<ref>Vinoth K. Ranganathan, Vlodek Siemionow, Vinod Sahgal, and Guang H. Yue, [https://agsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911240.x Effects of Aging on Hand Function] ''Journal of the American Geriatrics Society'' 49(11) (November 2001):1478–1484. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| − | * People over 35 years of age are at increasing risk for losing strength in the [[ciliary muscle]] of the [[eye]]s which leads to difficulty focusing on close objects, or [[presbyopia]].<ref>[https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/refractive-errors Refractive Errors] ''National Eye Institute''. Retrieved | + | * People over 35 years of age are at increasing risk for losing strength in the [[ciliary muscle]] of the [[eye]]s which leads to difficulty focusing on close objects, or [[presbyopia]].<ref>[https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/refractive-errors Refractive Errors] ''National Eye Institute''. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> Most people experience [[presbyopia]] by age 45–50. |

* Around age 50, [[hair]] turns grey. [[Pattern hair loss]] or [[baldness]] by the age of 50 affects about 50 percent of men and 25 percent of women. | * Around age 50, [[hair]] turns grey. [[Pattern hair loss]] or [[baldness]] by the age of 50 affects about 50 percent of men and 25 percent of women. | ||

* [[Menopause]] typically occurs between 44 and 58 years of age. | * [[Menopause]] typically occurs between 44 and 58 years of age. | ||

* In the 60–64 age cohort, the incidence of [[osteoarthritis]] rises. | * In the 60–64 age cohort, the incidence of [[osteoarthritis]] rises. | ||

* [[Wrinkle]]s develop mainly due to [[photoaging|photoageing]], particularly affecting sun-exposed areas (face). | * [[Wrinkle]]s develop mainly due to [[photoaging|photoageing]], particularly affecting sun-exposed areas (face). | ||

| − | * Almost half of people older than 75 have [[hearing loss]] (presbycusis) inhibiting spoken communication.<ref>[https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/hearing-loss-older-adults Hearing Loss and Older Adults] ''National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders''. Retrieved | + | * Almost half of people older than 75 have [[hearing loss]] (presbycusis) inhibiting spoken communication.<ref>[https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/hearing-loss-older-adults Hearing Loss and Older Adults] ''National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders''. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| − | * By age 80, more than half of all Americans either have a [[cataract]] or have had [[cataract surgery]].<ref>[https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/cataracts Cataracts] ''National Eye Institute''. Retrieved | + | * By age 80, more than half of all Americans either have a [[cataract]] or have had [[cataract surgery]].<ref>[https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/cataracts Cataracts] ''National Eye Institute''. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| − | * [[Frailty syndrome|Frailty]], a syndrome of decreased strength, physical activity, physical performance and energy, affects 25 percent of those over 85.<ref>L.P. Fried, C.M. Tangen, J. Walston, A.B. Newman, C. Hirsch, J. Gottdiener, T. Seeman, R. Tracy, W.J. Kop, G. Burke, and M.A. McBurnie, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11253156/ Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype] ''The Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences'' 56(3) (March 2001): M146-156. Retrieved | + | * [[Frailty syndrome|Frailty]], a syndrome of decreased strength, physical activity, physical performance and energy, affects 25 percent of those over 85.<ref>L.P. Fried, C.M. Tangen, J. Walston, A.B. Newman, C. Hirsch, J. Gottdiener, T. Seeman, R. Tracy, W.J. Kop, G. Burke, and M.A. McBurnie, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11253156/ Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype] ''The Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences'' 56(3) (March 2001): M146-156. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> |

| − | * [[Atherosclerosis]] is classified as an aging disease, which leads to cardiovascular disease (for example [[stroke]] and [[Myocardial infarction|heart attack]]), globally the most common causes of death.<ref>[https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death The top 10 causes of death] ''World Health Organization'', December 9, 2020. Retrieved | + | * [[Atherosclerosis]] is classified as an aging disease, which leads to cardiovascular disease (for example [[stroke]] and [[Myocardial infarction|heart attack]]), globally the most common causes of death.<ref>[https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death The top 10 causes of death] ''World Health Organization'', December 9, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

*[[Dementia]] becomes more common with age. The spectrum ranges from [[mild cognitive impairment]] to the neurodegenerative diseases of [[Alzheimer's disease]], [[cerebrovascular disease]], [[Parkinson's disease]] and [[Lou Gehrig's disease]]. bout 3 percent of people between the ages of 65 and 74, 19 percent between 75 and 84, and nearly half of those over 85 years of age have dementia.<ref> Rolando T. Lazaro, Sandra G. Reina-Guerra, and Myla Quiben, ''Umphred's Neurological Rehabilitation'' (Mosby, 2019, ISBN 0323611176).</ref> Furthermore, many types of [[Memory and aging|memory decline with aging]], but not [[semantic memory]] or general knowledge such as vocabulary definitions, which typically increases or remains steady until late adulthood.<ref>K. Warner Schaie, ''Developmental Influences on Adult Intelligence'' (Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0195386132). </ref> Individual variations in rate of cognitive decline may be explained in terms of people having different lengths of life.<ref>Ian Stuart-Hamilton, ''The Psychology of Ageing: An Introduction'' (Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2012, ISBN 184905245X).</ref> | *[[Dementia]] becomes more common with age. The spectrum ranges from [[mild cognitive impairment]] to the neurodegenerative diseases of [[Alzheimer's disease]], [[cerebrovascular disease]], [[Parkinson's disease]] and [[Lou Gehrig's disease]]. bout 3 percent of people between the ages of 65 and 74, 19 percent between 75 and 84, and nearly half of those over 85 years of age have dementia.<ref> Rolando T. Lazaro, Sandra G. Reina-Guerra, and Myla Quiben, ''Umphred's Neurological Rehabilitation'' (Mosby, 2019, ISBN 0323611176).</ref> Furthermore, many types of [[Memory and aging|memory decline with aging]], but not [[semantic memory]] or general knowledge such as vocabulary definitions, which typically increases or remains steady until late adulthood.<ref>K. Warner Schaie, ''Developmental Influences on Adult Intelligence'' (Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0195386132). </ref> Individual variations in rate of cognitive decline may be explained in terms of people having different lengths of life.<ref>Ian Stuart-Hamilton, ''The Psychology of Ageing: An Introduction'' (Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2012, ISBN 184905245X).</ref> | ||

== Prevention and delay == | == Prevention and delay == | ||

| − | + | Human beings who do not have a belief in an [[afterlife]], the continued existence of an eternal [[spirit]] or [[soul]] after the [[death]] of their physical body, have sought ways to prevent aging and death, or at least to delay the process. Such research supports each individual's likelihood of living their full lifespan in good [[health]]. The following are factors which have been found to increase the length and quality of life. | |

===Lifestyle=== | ===Lifestyle=== | ||

| − | A healthy [[diet]] may reduce the effects of aging. For example, the [[Mediterranean diet]] is credited with lowering the risk of heart disease and early death. The major contributors to mortality risk reduction appear to be a higher consumption of vegetables, fish, fruits, nuts, and monounsaturated fatty acids ([[olive]] oil).<ref name>[https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/08/160829094040.htm Mediterranean diet associated with lower risk of early death in cardiovascular disease patients] ''European Society of Cardiology'', August 29, 2016. Retrieved | + | A healthy [[diet]] may reduce the effects of aging. For example, the [[Mediterranean diet]] is credited with lowering the risk of heart disease and early death. The major contributors to mortality risk reduction appear to be a higher consumption of vegetables, fish, fruits, nuts, and monounsaturated fatty acids ([[olive]] oil).<ref name>[https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/08/160829094040.htm Mediterranean diet associated with lower risk of early death in cardiovascular disease patients] ''European Society of Cardiology'', August 29, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> |

| − | Amount of [[sleep]] is related to mortality. People who live the longest report sleeping for six to seven hours each night, while the National Sleep Foundation recommends eight hours of sleep per night for optimal health. However, this range of sleep has not been shown to be causal in increasing life span, merely correlated with longer life which may be affected by various other factors. Studies linking longer or shorter sleep patterns to increased mortality do not necessarily imply that people should change their existing, and comfortable, sleep patterns. <ref> Rhonda Rowland, [https://edition.cnn.com/2002/HEALTH/02/14/sleep.study/index.html Experts challenge study linking sleep, life span] ''CNN'', February 15, 2002. Retrieved | + | Amount of [[sleep]] is related to mortality. People who live the longest report sleeping for six to seven hours each night, while the National Sleep Foundation recommends eight hours of sleep per night for optimal health. However, this range of sleep has not been shown to be causal in increasing life span, merely correlated with longer life which may be affected by various other factors. Studies linking longer or shorter sleep patterns to increased mortality do not necessarily imply that people should change their existing, and comfortable, sleep patterns. <ref> Rhonda Rowland, [https://edition.cnn.com/2002/HEALTH/02/14/sleep.study/index.html Experts challenge study linking sleep, life span] ''CNN'', February 15, 2002. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| − | [[Physical exercise]] may increase life expectancy. People who participate in moderate to high levels of physical exercise have a lower mortality rate compared to individuals who are not physically active.<ref> Claude Bouchard, Steven N. Blair, and William L. Haskell (eds.), ''Physical Activity and Health'' (Human Kinetics, 2012, ISBN 0736095411).</ref> Moderate levels of exercise have been correlated with preventing aging and improving quality of life by reducing inflammatory potential.<ref>Jeffrey A. Woods, Kenneth R. Wilund, Stephen A. Martin, and Brandon M. Kistler, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3320801/ Exercise, inflammation and aging] ''Aging and Disease'' 3(1) (February 2012): 130–140. Retrieved | + | [[Physical exercise]] may increase life expectancy. People who participate in moderate to high levels of physical exercise have a lower mortality rate compared to individuals who are not physically active.<ref> Claude Bouchard, Steven N. Blair, and William L. Haskell (eds.), ''Physical Activity and Health'' (Human Kinetics, 2012, ISBN 0736095411).</ref> Moderate levels of exercise have been correlated with preventing aging and improving quality of life by reducing inflammatory potential.<ref>Jeffrey A. Woods, Kenneth R. Wilund, Stephen A. Martin, and Brandon M. Kistler, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3320801/ Exercise, inflammation and aging] ''Aging and Disease'' 3(1) (February 2012): 130–140. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> Regular physical exercise has also been shown to have restorative properties for cognitive and brain function in old age.<ref>Arthur F. Kramer and Kirk I. Erickson, [https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1364661307001581 Capitalizing on cortical plasticity: influence of physical activity on cognition and brain function] ''Trends in Cognitive Sciences'' 11(8) (August 2007):342-348. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| − | Avoidance of [[chronic stress]] (as opposed to acute stress) is associated with a slower loss of [[telomere]]s in most but not all studies, and with decreased [[cortisol]] levels, both of which are factors in increasing morbidity and mortality. Stress can be countered by social connection, spirituality, and (for men more clearly than for women) married life, all of which are associated with longevity.<ref> Harold Koenig, Dana King, and Verna B. Carson, ''Handbook of Religion and Health'' (Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0195335953). </ref><ref> Lecia Bushak, [https://www.medicaldaily.com/married-vs-single-what-science-says-better-your-health-327878 Married Vs Single: What Science Says Is Better For Your Health] ''Medical Daily'', April 2, 2015. Retrieved | + | Avoidance of [[chronic stress]] (as opposed to acute stress) is associated with a slower loss of [[telomere]]s in most but not all studies, and with decreased [[cortisol]] levels, both of which are factors in increasing morbidity and mortality. Stress can be countered by social connection, [[spirituality]], and (for men more clearly than for women) [[married]] life, all of which are associated with longevity.<ref> Harold Koenig, Dana King, and Verna B. Carson, ''Handbook of Religion and Health'' (Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0195335953). </ref><ref> Lecia Bushak, [https://www.medicaldaily.com/married-vs-single-what-science-says-better-your-health-327878 Married Vs Single: What Science Says Is Better For Your Health] ''Medical Daily'', April 2, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

===Medical intervention=== | ===Medical intervention=== | ||

| Line 119: | Line 106: | ||

In the fielda of [[sociology]] and [[mental health]], ageing is seen in five different views: aging as [[Maturity (psychological)|maturity]], aging as decline, aging as a life-cycle event, aging as generation, and aging as survival.<ref>Teresa L. Scheid and Eric R. Wright (eds.), ''A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health'' (Cambridge University Press, 2017, ISBN 9781316500965).</ref> Positive correlates with aging often include economics, employment, marriage, children, education, and sense of control. [[Retirement]], a common transition faced by the elderly, may have both positive and negative consequences.<ref>Susan K. Whitbourne and Stacey B. Whitbourne, ''Adult Development and Aging'' (Wiley, 2020, ISBN 1119667453).</ref> | In the fielda of [[sociology]] and [[mental health]], ageing is seen in five different views: aging as [[Maturity (psychological)|maturity]], aging as decline, aging as a life-cycle event, aging as generation, and aging as survival.<ref>Teresa L. Scheid and Eric R. Wright (eds.), ''A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health'' (Cambridge University Press, 2017, ISBN 9781316500965).</ref> Positive correlates with aging often include economics, employment, marriage, children, education, and sense of control. [[Retirement]], a common transition faced by the elderly, may have both positive and negative consequences.<ref>Susan K. Whitbourne and Stacey B. Whitbourne, ''Adult Development and Aging'' (Wiley, 2020, ISBN 1119667453).</ref> | ||

| − | Population aging is the increase in the number and proportion of older people in society. Population aging occurs through [[human migration|migration]], longer [[life expectancy]] (decreased death rate), and decreased birth rate. As a population ages, it has a significant impact on society. Young people tend to have fewer legal privileges (if they are below the [[age of majority]]), they are more likely to push for political and social change, to develop and adopt new technologies, and to need education. Older people have different requirements from society and government, and frequently have differing values as well, such as for property and pension rights.<ref>John A. Vincent, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16309437/ Understanding generations: political economy and culture in an ageing society] ''The British Journal of Sociology'' 56(4) (December 2005): 579–599. Retrieved | + | Population aging is the increase in the number and proportion of older people in society. Population aging occurs through [[human migration|migration]], longer [[life expectancy]] (decreased death rate), and decreased birth rate. As a population ages, it has a significant impact on society. Young people tend to have fewer legal privileges (if they are below the [[age of majority]]), they are more likely to push for political and social change, to develop and adopt new technologies, and to need education. Older people have different requirements from society and government, and frequently have differing values as well, such as for property and pension rights.<ref>John A. Vincent, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16309437/ Understanding generations: political economy and culture in an ageing society] ''The British Journal of Sociology'' 56(4) (December 2005): 579–599. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

=== Economics === | === Economics === | ||

| − | Among the most urgent concerns of older persons worldwide is income security. This poses challenges for governments with aging populations to ensure that investment in pension systems is sufficient to provide economic independence and reduce poverty in old age. These challenges vary for developing and developed countries: <blockquote>Sustainability of these systems is of particular concern, particularly in developed countries, while social protection and old-age pension coverage remain a challenge for developing countries, where a large proportion of the labour force is found in the informal sector.<ref name=UNPF> Jose Miguel Guzman, Ann Pawliczko, Sylvia Beales, Celia Till, and Ina Voelcker (ed.), ''Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and a Challenge'' (United Nations Population Fund, HelpAge International, 2012, ISBN 0897149815).</ref></blockquote> | + | Among the most urgent concerns of older persons worldwide is income security. This poses challenges for governments with aging populations to ensure that investment in pension systems is sufficient to provide economic independence and reduce poverty in old age. These challenges vary for developing and developed countries: |

| + | <blockquote>Sustainability of these systems is of particular concern, particularly in developed countries, while social protection and old-age pension coverage remain a challenge for developing countries, where a large proportion of the labour force is found in the informal sector.<ref name=UNPF> Jose Miguel Guzman, Ann Pawliczko, Sylvia Beales, Celia Till, and Ina Voelcker (ed.), ''Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and a Challenge'' (United Nations Population Fund, HelpAge International, 2012, ISBN 0897149815).</ref></blockquote> | ||

| − | === Health care | + | === Health care === |

With age inevitable biological changes occur that increase the risk of illness and disability. A number of health problems become more prevalent as people get older. These include [[mental health]] problems as well as physical health problems, especially [[dementia]]. | With age inevitable biological changes occur that increase the risk of illness and disability. A number of health problems become more prevalent as people get older. These include [[mental health]] problems as well as physical health problems, especially [[dementia]]. | ||

| Line 131: | Line 119: | ||

===Self-perception=== | ===Self-perception=== | ||

| − | As humans age, their bodies begin to break down, and among other changes their skin begins to look different. However, especially in Western culture, these changes are not always appreciated and being young or at least youthful is celebrated especially when young people are successful.<ref>Carolyn Gregoire, [https://www.huffpost.com/entry/why-30-under-30-lists-mis_n_4791178 Here's Everything That's Wrong With Our 'Under 30' Obsession] ''Huffington Post'', February 25, 2014. Retrieved | + | As humans age, their bodies begin to break down, and among other changes their skin begins to look different. However, especially in Western culture, these changes are not always appreciated and being young, or at least youthful, is celebrated especially when young people are successful.<ref>Carolyn Gregoire, [https://www.huffpost.com/entry/why-30-under-30-lists-mis_n_4791178 Here's Everything That's Wrong With Our 'Under 30' Obsession] ''Huffington Post'', February 25, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| − | Generally, aversion to aging and its effects is primarily a Western attitude. In other places around the world, old age is celebrated and honored. In Korea, for example, a special party called ''[[hwangap]]'' is held to celebrate and congratulate an individual for turning 60 years old.<ref>[http://www.asianinfo.org/asianinfo/korea/cel/birthday_celebrations.htm Korea - Birthday Celebrations] ''Asian Info''. Retrieved | + | Generally, aversion to aging and its effects is primarily a Western attitude. In other places around the world, old age is celebrated and honored. In Korea, for example, a special party called ''[[hwangap]]'' is held to celebrate and congratulate an individual for turning 60 years old.<ref>[http://www.asianinfo.org/asianinfo/korea/cel/birthday_celebrations.htm Korea - Birthday Celebrations] ''Asian Info''. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| − | Positive self-perceptions of aging are associated with better mental and physical health and well-being.<ref>Serena Sabatini, Barbora Silarova, Anthony Martyr, Rachel Collins, Clive Ballard, Kaarin J. Anstey, Sarang Kim, and Linda Clare, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31350849/ Associations of Awareness of Age-Related Change With Emotional and Physical Well-being: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis] ''The Gerontologist'' 60(6) (August 2020): e477–e490. Retrieved | + | Positive self-perceptions of aging are associated with better mental and physical health and well-being.<ref>Serena Sabatini, Barbora Silarova, Anthony Martyr, Rachel Collins, Clive Ballard, Kaarin J. Anstey, Sarang Kim, and Linda Clare, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31350849/ Associations of Awareness of Age-Related Change With Emotional and Physical Well-being: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis] ''The Gerontologist'' 60(6) (August 2020): e477–e490. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> Positive self-perception of [[health]] has been correlated with higher well-being and reduced mortality among the elderly. Various reasons have been proposed for this association; people who are objectively healthy may naturally rate their health better as than that of their ill counterparts. |

As people age, subjective health remains relatively stable, even though objective health worsens. In fact, perceived health improves with age when objective health is controlled in the equation. This phenomenon is known as the "paradox of aging," and may be a result of [[social comparison]]; for instance, the older people get, the more they may consider themselves in better health than their same-aged peers. Elderly people often associate their functional and physical decline with the normal aging process.<ref>Jutta Heckhausen, ''Developmental Regulation in Adulthood: Age-Normative and Sociostructural Constraints as Adaptive Challenges'' (Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521027136). </ref> | As people age, subjective health remains relatively stable, even though objective health worsens. In fact, perceived health improves with age when objective health is controlled in the equation. This phenomenon is known as the "paradox of aging," and may be a result of [[social comparison]]; for instance, the older people get, the more they may consider themselves in better health than their same-aged peers. Elderly people often associate their functional and physical decline with the normal aging process.<ref>Jutta Heckhausen, ''Developmental Regulation in Adulthood: Age-Normative and Sociostructural Constraints as Adaptive Challenges'' (Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521027136). </ref> | ||

===Successful aging=== | ===Successful aging=== | ||

| − | Traditional definitions of successful aging have emphasized absence of physical and cognitive disabilities.<ref>Paul B. Baltes and Margaret M. Baltes, ''Successful Aging'' (Cambridge University Press, 1993, ISBN 052143582X). </ref> Successful aging has been characterized as involving three components: a) freedom from disease and disability, b) high cognitive and physical functioning, and c) social and productive engagement.<ref>J.W. Rowe and R.L. Kahn, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3299702/ Human aging: usual and successful] ''Science'' 237(4811) (July 1987): 143–149. Retrieved | + | Traditional definitions of successful aging have emphasized absence of physical and cognitive disabilities.<ref>Paul B. Baltes and Margaret M. Baltes, ''Successful Aging'' (Cambridge University Press, 1993, ISBN 052143582X). </ref> Successful aging has been characterized as involving three components: a) freedom from disease and disability, b) high cognitive and physical functioning, and c) social and productive engagement.<ref>J.W. Rowe and R.L. Kahn, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/3299702/ Human aging: usual and successful] ''Science'' 237(4811) (July 1987): 143–149. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

== Notes == | == Notes == | ||

| Line 152: | Line 140: | ||

*Koenig, Harold, Dana King, and Verna B. Carson. ''Handbook of Religion and Health''. Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 0195335953 | *Koenig, Harold, Dana King, and Verna B. Carson. ''Handbook of Religion and Health''. Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 0195335953 | ||

*Lazaro, Rolando T., Sandra G. Reina-Guerra, and Myla Quiben. ''Umphred's Neurological Rehabilitation''. Mosby, 2019. ISBN 0323611176 | *Lazaro, Rolando T., Sandra G. Reina-Guerra, and Myla Quiben. ''Umphred's Neurological Rehabilitation''. Mosby, 2019. ISBN 0323611176 | ||

| + | *Masoro, Edward J., and Steven N. Austad (eds.). ''Handbook of the Biology of Aging''. Academic Press, 2006. ISBN 0120883872 | ||

*McDonald, Roger B. ''Biology of Aging''. Garland Science, 2019. ISBN 0815345674 | *McDonald, Roger B. ''Biology of Aging''. Garland Science, 2019. ISBN 0815345674 | ||

*Phillips, Judith, Kristine Ajrouch, and Sarah Hillcoat-Nallétamby. ''Key Concepts in Social Gerontology''. SAGE Publications, 2010. ISBN 1412922720 | *Phillips, Judith, Kristine Ajrouch, and Sarah Hillcoat-Nallétamby. ''Key Concepts in Social Gerontology''. SAGE Publications, 2010. ISBN 1412922720 | ||

| Line 160: | Line 149: | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | All links retrieved | + | All links retrieved June 16, 2023. |

* [https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/aging.html Aging and Death in Folklore] | * [https://sites.pitt.edu/~dash/aging.html Aging and Death in Folklore] | ||

* [https://www.helpage.org/global-agewatch/ Global AgeWatch] | * [https://www.helpage.org/global-agewatch/ Global AgeWatch] | ||

* [https://www.helpage.org/resources/ageing-in-the-21st-century-a-celebration-and-a-challenge/ Ageing in the 21st Century] ''HelpAge International'' | * [https://www.helpage.org/resources/ageing-in-the-21st-century-a-celebration-and-a-challenge/ Ageing in the 21st Century] ''HelpAge International'' | ||

| − | + | * [https://www.nia.nih.gov/ National Institute on Aging] | |

| − | + | * [https://www.mayoclinic.org/healthy-lifestyle/healthy-aging/in-depth/aging/art-20046070 Healthy aging] ''Mayo Clinic'' | |

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

[[Category:Social sciences]] | [[Category:Social sciences]] | ||

{{Credits|Ageing|1023559864}} | {{Credits|Ageing|1023559864}} | ||

Latest revision as of 06:45, 16 June 2023

Aging or ageing is the process of becoming older. The term refers especially to humans, many other animals, and fungi. In the broader sense, aging can refer to single cells within an organism which have ceased dividing (cellular senescence) or to the population of a species (population aging).

This article focuses primarily on humans. Aging represents the accumulation of changes in a human being over time and can encompass physical, psychological, and social changes. Reaction time, for example, may slow with age, while memories and general knowledge typically increase. Society's view of aging, for example valuing youth over experience, affects a person's self-perception of their own aging. A belief in an afterlife, the continued existence of an eternal spirit or soul after the death of the physical body, gives a different view to aging and reduces the stress associated with physical deterioration.

Definitions

Biological aging refers to an organism's increased rate of death as it progresses through its lifecycle and increases its chronological age.[1] Another possible way to define aging is through functional definitions, of which there are two main types: The first describes how varying types of deteriorative changes that accumulate in the life of a post-maturation organism can leave it vulnerable, leading to a decreased ability of the organism to survive: "Aging is the progressive accumulation of changes with time that are associated with or responsible for the ever-increasing susceptibility to disease and death which accompanies advancing age."[2] The second is a senescence-based definition which describes age-related changes in an organism that increase its mortality rate over time by negatively affecting its vitality and functional performance.[1]

An important distinction to make is that biological aging is not the same as the accumulation of diseases related to old age; disease is a blanket term used to describe a process within an organism that causes a decrease in its functional ability.[1] Aging is the natural and inevitable biological process that all animal life, including human beings, go through from conception through birth to death. While death by other external causes, such as disease, accident, predation, and so forth, is common, nonetheless death would occur naturally due to aging even in the absence of such causes.

Biological basis

The causes of aging are uncertain, but appear to involve a number of factors.[3] The factors proposed to influence biological aging fall into two main categories: programmed and damage-related. They are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

The first posits that aging is programmed and therefore follows an inexorable path, a biological timetable, perhaps one that might be a continuation of that which regulates childhood growth and development. This regulation would depend on changes in gene expression that affect the systems responsible for maintenance, repair, and defense responses. Programmed aging should not be confused with programmed cell death (apoptosis).

The second category of theories suggests various sources and targets of damage that lead to aging. Damage-related factors include internal and environmental assaults to living organisms that induce cumulative damage at various levels.

A third, novel concept is that aging is mediated by vicious cycles.[4]

Additionally, there can be other reasons which can speed up the rate of aging in organisms including human beings, such as obesity and compromised immune system.

Programmed factors

The programmed approach suggests three major mechanisms which control aging:[5]

- Programmed Longevity

Aging is the result of a sequential switching on and off of certain genes, with senescence being defined as the time when age-associated deficits are manifested.

- Endocrine Theory

Biological clocks act through hormones to control the pace of aging.

- Immunological Theory

The immune system is programmed to decline over time, which leads to an increased vulnerability to infectious diseases and thus aging and death.

The rate of aging varies substantially across different species, and this, to a large extent, is genetically based. For example, numerous perennial plants ranging from strawberries and potatoes to willow trees typically produce clones of themselves by vegetative reproduction and are thus potentially immortal, while annual plants such as wheat and watermelons die each year and reproduce by sexual reproduction. The oldest animals known so far are 15,000-year-old Antarctic sponges,[6] which can reproduce both sexually and clonally.

Clonal immortality apart, there are certain species whose individual lifespans stand out among Earth's life-forms, including the bristlecone pine at around 5,000 years[7] invertebrates like the hard clam (known as quahog in New England) at 508 years,[8] the Greenland shark at 400 years,[9] various deep-sea tube worms at over 300 years,[10] and lobsters.[11] Such organisms are sometimes said to exhibit negligible senescence.[12]

Numerous damage-related factors have been proposed that lead to aging, including the following:[5]

- Wear and tear theory

Cells and tissues have vital parts that wear out resulting in aging. Like components of an aging machine, parts of the body eventually wear out from repeated use, leading to cell death and inability to function.

- Rate of living theory

This suggests that the greater an organism’s rate of oxygen basal metabolism, the shorter its life span. While helpful, this does not explain maximum life span.

- Cross-linking theory

According to this theory, an accumulation of cross-linked proteins damages cells and tissues, slowing down bodily processes and resulting in aging.

- Free radical theory

This proposes that free radicals cause damage to the macromolecular components of the cell, giving rise to accumulated damage causing cells, and eventually organs, to stop functioning. Macromolecules, such as nucleic acids, lipids, sugars, and proteins, are susceptible to free radical attack. Enzymes, which are natural antioxidants, are found in the body and function to curb build-up of free radicals.

- Somatic DNA damage theory

DNA damage occurs continuously in cells of living organisms. While most of the damage is repaired naturally, some accumulates as the repair mechanisms cannot correct defects as fast as they are produced. Thus, aging results from damage to the genetic integrity of the body’s cells.

Other suggested factors include: progressive loss of physiological integrity through genomic instability (mutations accumulated in nuclear DNA, in mtDNA, and in the nuclear lamina) and telomere attrition.[13] Also, accumulation of waste products in cells presumably interferes with metabolism. For example, a waste product called lipofuscin is formed by a complex reaction in cells that binds fat to proteins. This waste accumulates in the cells as small granules, which increase in size as a person ages.[14]

Effects

In humans, aging represents the accumulation of changes in a human being over time and can encompass physical, psychological, and social changes. Reaction time, for example, may slow with age, while memories and general knowledge typically increase. Aging also increases the risk of diseases.

A number of characteristic aging symptoms are experienced by a significant proportion of human beings during their lifetimes, including the following:

- After peaking in the mid-20s, female fertility declines.[17]

- After age 30 the mass of human body is decreased until 70 years and then shows damping oscillations.[16]

- Muscles have reduced capacity of responding to exercise or injury and loss of muscle mass and strength (sarcopenia) is common.[18]

- Hand strength and mobility are decreased during the aging process. These things include "hand and finger strength and ability to control submaximal pinch force and maintain a steady precision pinch posture, manual speed, and hand sensation."[19]

- People over 35 years of age are at increasing risk for losing strength in the ciliary muscle of the eyes which leads to difficulty focusing on close objects, or presbyopia.[20] Most people experience presbyopia by age 45–50.

- Around age 50, hair turns grey. Pattern hair loss or baldness by the age of 50 affects about 50 percent of men and 25 percent of women.

- Menopause typically occurs between 44 and 58 years of age.

- In the 60–64 age cohort, the incidence of osteoarthritis rises.

- Wrinkles develop mainly due to photoageing, particularly affecting sun-exposed areas (face).

- Almost half of people older than 75 have hearing loss (presbycusis) inhibiting spoken communication.[21]

- By age 80, more than half of all Americans either have a cataract or have had cataract surgery.[22]

- Frailty, a syndrome of decreased strength, physical activity, physical performance and energy, affects 25 percent of those over 85.[23]

- Atherosclerosis is classified as an aging disease, which leads to cardiovascular disease (for example stroke and heart attack), globally the most common causes of death.[24]

- Dementia becomes more common with age. The spectrum ranges from mild cognitive impairment to the neurodegenerative diseases of Alzheimer's disease, cerebrovascular disease, Parkinson's disease and Lou Gehrig's disease. bout 3 percent of people between the ages of 65 and 74, 19 percent between 75 and 84, and nearly half of those over 85 years of age have dementia.[25] Furthermore, many types of memory decline with aging, but not semantic memory or general knowledge such as vocabulary definitions, which typically increases or remains steady until late adulthood.[26] Individual variations in rate of cognitive decline may be explained in terms of people having different lengths of life.[27]

Prevention and delay

Human beings who do not have a belief in an afterlife, the continued existence of an eternal spirit or soul after the death of their physical body, have sought ways to prevent aging and death, or at least to delay the process. Such research supports each individual's likelihood of living their full lifespan in good health. The following are factors which have been found to increase the length and quality of life.

Lifestyle

A healthy diet may reduce the effects of aging. For example, the Mediterranean diet is credited with lowering the risk of heart disease and early death. The major contributors to mortality risk reduction appear to be a higher consumption of vegetables, fish, fruits, nuts, and monounsaturated fatty acids (olive oil).[28]

Amount of sleep is related to mortality. People who live the longest report sleeping for six to seven hours each night, while the National Sleep Foundation recommends eight hours of sleep per night for optimal health. However, this range of sleep has not been shown to be causal in increasing life span, merely correlated with longer life which may be affected by various other factors. Studies linking longer or shorter sleep patterns to increased mortality do not necessarily imply that people should change their existing, and comfortable, sleep patterns. [29]

Physical exercise may increase life expectancy. People who participate in moderate to high levels of physical exercise have a lower mortality rate compared to individuals who are not physically active.[30] Moderate levels of exercise have been correlated with preventing aging and improving quality of life by reducing inflammatory potential.[31] Regular physical exercise has also been shown to have restorative properties for cognitive and brain function in old age.[32]

Avoidance of chronic stress (as opposed to acute stress) is associated with a slower loss of telomeres in most but not all studies, and with decreased cortisol levels, both of which are factors in increasing morbidity and mortality. Stress can be countered by social connection, spirituality, and (for men more clearly than for women) married life, all of which are associated with longevity.[33][34]

Medical intervention

Theoretically, extension of maximum lifespan in humans could be achieved by reducing the rate of aging damage by periodic replacement of damaged tissues, molecular repair or rejuvenation of deteriorated cells and tissues, reversal of harmful epigenetic changes, or the enhancement of enzyme telomerase activity. Research geared towards life extension strategies in various organisms is currently under way at a number of academic and private institutions. Various drugs and interventions have been shown to slow or reverse the biological effects of aging in animal models, but none has yet been proven to do so in humans.

Society and culture

Different cultures express age in different ways. Most legal systems define a specific age for when an individual is allowed or obliged to do particular activities. These age specifications include voting age, drinking age, age of consent, age of majority, age of criminal responsibility, marriageable age, age of candidacy, and mandatory retirement age. In other words, chronological aging may be distinguished from "social aging" (cultural age-expectations of how people should act as they grow older) and "biological aging" (an organism's physical state as it ages).[35]

Sociology

In the fielda of sociology and mental health, ageing is seen in five different views: aging as maturity, aging as decline, aging as a life-cycle event, aging as generation, and aging as survival.[36] Positive correlates with aging often include economics, employment, marriage, children, education, and sense of control. Retirement, a common transition faced by the elderly, may have both positive and negative consequences.[37]

Population aging is the increase in the number and proportion of older people in society. Population aging occurs through migration, longer life expectancy (decreased death rate), and decreased birth rate. As a population ages, it has a significant impact on society. Young people tend to have fewer legal privileges (if they are below the age of majority), they are more likely to push for political and social change, to develop and adopt new technologies, and to need education. Older people have different requirements from society and government, and frequently have differing values as well, such as for property and pension rights.[38]

Economics

Among the most urgent concerns of older persons worldwide is income security. This poses challenges for governments with aging populations to ensure that investment in pension systems is sufficient to provide economic independence and reduce poverty in old age. These challenges vary for developing and developed countries:

Sustainability of these systems is of particular concern, particularly in developed countries, while social protection and old-age pension coverage remain a challenge for developing countries, where a large proportion of the labour force is found in the informal sector.[39]

Health care

With age inevitable biological changes occur that increase the risk of illness and disability. A number of health problems become more prevalent as people get older. These include mental health problems as well as physical health problems, especially dementia.

While the effects on society of population aging are multidimensional, there is no doubt about its impact on health care demand:

A life-cycle approach to health care – one that starts early, continues through the reproductive years and lasts into old age – is essential for the physical and emotional well-being of older persons, and, indeed, all people. Public policies and programmes should additionally address the needs of older impoverished people who cannot afford health care.[39]

Self-perception

As humans age, their bodies begin to break down, and among other changes their skin begins to look different. However, especially in Western culture, these changes are not always appreciated and being young, or at least youthful, is celebrated especially when young people are successful.[40]

Generally, aversion to aging and its effects is primarily a Western attitude. In other places around the world, old age is celebrated and honored. In Korea, for example, a special party called hwangap is held to celebrate and congratulate an individual for turning 60 years old.[41]

Positive self-perceptions of aging are associated with better mental and physical health and well-being.[42] Positive self-perception of health has been correlated with higher well-being and reduced mortality among the elderly. Various reasons have been proposed for this association; people who are objectively healthy may naturally rate their health better as than that of their ill counterparts.

As people age, subjective health remains relatively stable, even though objective health worsens. In fact, perceived health improves with age when objective health is controlled in the equation. This phenomenon is known as the "paradox of aging," and may be a result of social comparison; for instance, the older people get, the more they may consider themselves in better health than their same-aged peers. Elderly people often associate their functional and physical decline with the normal aging process.[43]

Successful aging

Traditional definitions of successful aging have emphasized absence of physical and cognitive disabilities.[44] Successful aging has been characterized as involving three components: a) freedom from disease and disability, b) high cognitive and physical functioning, and c) social and productive engagement.[45]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Roger B. McDonald, Biology of Aging (Garland Science, 2019, ISBN 0815345674).

- ↑ D. Harman, The aging process Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 78(11) (November 1981): 7124–7128. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Stefan I. Liochev, Which Is the Most Significant Cause of Aging? Antioxidants (Basel) 4(4) (December 2015): 793–810. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Aleksey V. Belikov, Age-related diseases as vicious cycles Ageing Research Reviews 49 (January 2019): 11–26. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kunlin Jin, Modern Biological Theories of Aging Aging Dis. 1(2) (October 2010): 72–74. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Marnie Chesterton, The oldest living thing on Earth BBC News, June 12, 2017. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Oldlist Rocky Mountain Tree Ring Research. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Danuta Sosnowska, Chris Richardson, William E. Sonntag, Anna Csiszar, Zoltan Ungvari, and Iain Ridgway, A heart that beats for 500 years The Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 69(12) (December 2014): 1448–1461. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ J. Nielsen, et al, Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) Science 353(6300) (August 2016): 702–704. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Alanna Durkin, Charles R. Fisher, Erik E. Cordes, Extreme longevity in a deep-sea vestimentiferan tubeworm and its implications for the evolution of life history strategies The Science of Nature 104(7–8) (August 2017): 63. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Jacob Silverman, Is there a 400 pound lobster out there? How Stuff Works. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ John C. Guerin, Emerging area of aging research: long-lived animals with "negligible senescence" Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1019(1) (June 2004): 518–520. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Carlos López-Otín, Maria A. Blasco, Linda Partridge, Manuel Serrano, and Guido Kroemer, The Hallmarks of Aging Cell 153(6) (June 2013): 1194–1217. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Edward J. Masoro and Steven N. Austad (eds.), Handbook of the Biology of Aging (Academic Press, 2006, ISBN 0120883872).

- ↑ Stephen Moss, Big ears: they really do grow as we age The Guardian, July 17, 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 I. G. Gerasimov and Dmitry Yu Ignatov, Age Dynamics of Body Mass and Human Lifespan Journal of Evolutionary Biochemistry and Physiology 40(3) (2004):343–349. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Infertility: Overview Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care, March 25, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ James G. Ryall, Jonathan D. Schertzer, and Gordon S. Lynch, Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and weakness Biogerontology 9(4) (August 2008): 213–228. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Vinoth K. Ranganathan, Vlodek Siemionow, Vinod Sahgal, and Guang H. Yue, Effects of Aging on Hand Function Journal of the American Geriatrics Society 49(11) (November 2001):1478–1484. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Refractive Errors National Eye Institute. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Hearing Loss and Older Adults National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Cataracts National Eye Institute. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ L.P. Fried, C.M. Tangen, J. Walston, A.B. Newman, C. Hirsch, J. Gottdiener, T. Seeman, R. Tracy, W.J. Kop, G. Burke, and M.A. McBurnie, Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype The Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 56(3) (March 2001): M146-156. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ The top 10 causes of death World Health Organization, December 9, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Rolando T. Lazaro, Sandra G. Reina-Guerra, and Myla Quiben, Umphred's Neurological Rehabilitation (Mosby, 2019, ISBN 0323611176).

- ↑ K. Warner Schaie, Developmental Influences on Adult Intelligence (Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0195386132).

- ↑ Ian Stuart-Hamilton, The Psychology of Ageing: An Introduction (Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2012, ISBN 184905245X).

- ↑ Mediterranean diet associated with lower risk of early death in cardiovascular disease patients European Society of Cardiology, August 29, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Rhonda Rowland, Experts challenge study linking sleep, life span CNN, February 15, 2002. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Claude Bouchard, Steven N. Blair, and William L. Haskell (eds.), Physical Activity and Health (Human Kinetics, 2012, ISBN 0736095411).

- ↑ Jeffrey A. Woods, Kenneth R. Wilund, Stephen A. Martin, and Brandon M. Kistler, Exercise, inflammation and aging Aging and Disease 3(1) (February 2012): 130–140. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Arthur F. Kramer and Kirk I. Erickson, Capitalizing on cortical plasticity: influence of physical activity on cognition and brain function Trends in Cognitive Sciences 11(8) (August 2007):342-348. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Harold Koenig, Dana King, and Verna B. Carson, Handbook of Religion and Health (Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0195335953).

- ↑ Lecia Bushak, Married Vs Single: What Science Says Is Better For Your Health Medical Daily, April 2, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Judith Phillips, Kristine Ajrouch, and Sarah Hillcoat-Nallétamby, Key Concepts in Social Gerontology (SAGE Publications, 2010, ISBN 1412922720).

- ↑ Teresa L. Scheid and Eric R. Wright (eds.), A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health (Cambridge University Press, 2017, ISBN 9781316500965).

- ↑ Susan K. Whitbourne and Stacey B. Whitbourne, Adult Development and Aging (Wiley, 2020, ISBN 1119667453).

- ↑ John A. Vincent, Understanding generations: political economy and culture in an ageing society The British Journal of Sociology 56(4) (December 2005): 579–599. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 Jose Miguel Guzman, Ann Pawliczko, Sylvia Beales, Celia Till, and Ina Voelcker (ed.), Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and a Challenge (United Nations Population Fund, HelpAge International, 2012, ISBN 0897149815).

- ↑ Carolyn Gregoire, Here's Everything That's Wrong With Our 'Under 30' Obsession Huffington Post, February 25, 2014. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Korea - Birthday Celebrations Asian Info. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Serena Sabatini, Barbora Silarova, Anthony Martyr, Rachel Collins, Clive Ballard, Kaarin J. Anstey, Sarang Kim, and Linda Clare, Associations of Awareness of Age-Related Change With Emotional and Physical Well-being: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis The Gerontologist 60(6) (August 2020): e477–e490. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

- ↑ Jutta Heckhausen, Developmental Regulation in Adulthood: Age-Normative and Sociostructural Constraints as Adaptive Challenges (Cambridge University Press, 2006, ISBN 0521027136).

- ↑ Paul B. Baltes and Margaret M. Baltes, Successful Aging (Cambridge University Press, 1993, ISBN 052143582X).

- ↑ J.W. Rowe and R.L. Kahn, Human aging: usual and successful Science 237(4811) (July 1987): 143–149. Retrieved May 31, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baltes, Paul B., and Margaret M. Baltes. Successful Aging. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 052143582X

- Bouchard, Claude, Steven N. Blair, and William L. Haskell (eds.). Physical Activity and Health. Human Kinetics, 2012. ISBN 0736095411

- Guzman, Jose Miguel, Ann Pawliczko, Sylvia Beales, Celia Till, and Ina Voelcker (eds.). Ageing in the Twenty-First Century: A Celebration and a Challenge. United Nations Population Fund, HelpAge International, 2012. ISBN 0897149815

- Heckhausen, Jutta. Developmental Regulation in Adulthood: Age-Normative and Sociostructural Constraints as Adaptive Challenges. Cambridge University Press, 2006. ISBN 0521027136

- Koenig, Harold, Dana King, and Verna B. Carson. Handbook of Religion and Health. Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 0195335953

- Lazaro, Rolando T., Sandra G. Reina-Guerra, and Myla Quiben. Umphred's Neurological Rehabilitation. Mosby, 2019. ISBN 0323611176

- Masoro, Edward J., and Steven N. Austad (eds.). Handbook of the Biology of Aging. Academic Press, 2006. ISBN 0120883872

- McDonald, Roger B. Biology of Aging. Garland Science, 2019. ISBN 0815345674

- Phillips, Judith, Kristine Ajrouch, and Sarah Hillcoat-Nallétamby. Key Concepts in Social Gerontology. SAGE Publications, 2010. ISBN 1412922720

- Schaie, K. Warner. Developmental Influences on Adult Intelligence. Oxford University Press, 2012. ISBN 0195386132

- Scheid, Teresa L., and Eric R. Wright (eds.). A Handbook for the Study of Mental Health. Cambridge University Press, 2017. ISBN 9781316500965

- Stuart-Hamilton, Ian. The Psychology of Ageing: An Introduction. Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2012. ISBN 184905245X

- Whitbourne, Susan K., and Stacey B. Whitbourne. Adult Development and Aging. Wiley, 2020. ISBN 1119667453

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2023.

- Aging and Death in Folklore

- Global AgeWatch

- Ageing in the 21st Century HelpAge International

- National Institute on Aging

- Healthy aging Mayo Clinic

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.