|

|

| (69 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | '''Currently working on''' —[[User:Jennifer Tanabe|Jennifer Tanabe]] May 2021.

| + | {{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Approved}}{{Copyedited}} |

| | | | |

| | [[File:Old woman with young baby boy.JPG|thumb|right|300px|95-year-old woman holding a five-month-old boy]] | | [[File:Old woman with young baby boy.JPG|thumb|right|300px|95-year-old woman holding a five-month-old boy]] |

| | | | |

| − | '''Aging''' or '''ageing''' is the process of becoming older. The term refers especially to [[human]]s, many other animals, and [[fungi]]. In the broader sense, aging can refer to single cells within an organism which have ceased dividing ([[cellular senescence]]) or to the population of a species ([[population aging]]). | + | '''Aging''' or '''ageing''' is the process of becoming older. The term refers especially to [[human]]s, many other [[animal]]s, and [[fungi]]. In the broader sense, aging can refer to single cells within an [[organism]] which have ceased dividing ([[cellular senescence]]) or to the population of a species ([[population aging]]). |

| − | | + | {{toc}} |

| − | In humans, aging represents the accumulation of changes in a human being over time and can encompass [[Human body|physical]], [[psychological]], and social changes. Reaction time, for example, may slow with age, while memories and general knowledge typically increase.

| + | This article focuses primarily on humans. Aging represents the accumulation of changes in a [[human being]] over time and can encompass [[Human body|physical]], [[psychological]], and social changes. Reaction time, for example, may slow with age, while memories and general knowledge typically increase. Society's view of aging, for example valuing youth over experience, affects a person's self-perception of their own aging. A belief in an [[afterlife]], the continued existence of an eternal [[spirit]] or [[soul]] after the [[death]] of the physical body, gives a different view to aging and reduces the stress associated with physical deterioration. |

| − | | |

| | | | |

| | == Definitions == | | == Definitions == |

| − | Mortality can be used to define biological aging, which refers to an organism's increased rate of death as it progresses throughout its lifecycle and increases its chronological age.<ref name=McDonald>Roger B. McDonald, ''Biology of Aging'' (Garland Science, 2019, ISBN 0815345674).</ref> Another possible way to define aging is through functional definitions, of which there are two main types: The first describes how varying types of deteriorative changes that accumulate in the life of a post-maturation organism can leave it vulnerable, leading to a decreased ability of the organism to survive. The second is a senescence-based definition which describes age-related changes in an organism that increase its mortality rate over time by negatively affecting its vitality and functional performance.<ref name=McDonald/>

| + | Biological aging refers to an [[organism]]'s increased rate of death as it progresses through its lifecycle and increases its chronological age.<ref name=McDonald>Roger B. McDonald, ''Biology of Aging'' (Garland Science, 2019, ISBN 0815345674).</ref> Another possible way to define aging is through functional definitions, of which there are two main types: The first describes how varying types of deteriorative changes that accumulate in the life of a post-maturation organism can leave it vulnerable, leading to a decreased ability of the organism to survive: "Aging is the progressive accumulation of changes with time that are associated with or responsible for the ever-increasing susceptibility to disease and death which accompanies advancing age."<ref>D. Harman, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC349208/ The aging process] ''Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A'' 78(11) (November 1981): 7124–7128. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> The second is a senescence-based definition which describes age-related changes in an organism that increase its mortality rate over time by negatively affecting its vitality and functional performance.<ref name=McDonald/> |

| − | | + | {{readout||right|250px|Aging is the natural biological process that all [[animal]] life, including [[human being]]s, go through from conception to [[death]]}} |

| − | An important distinction to make is that biological aging is not the same thing as the accumulation of [[disease]]s related to old age; ''disease'' is a blanket term used to describe a process within an organism that causes a decrease in its functional ability.<ref name=McDonald/> Aging is the natural and inevitable biological process that all [[animal]] life, including [[human being]]s go through from conception through birth to [[death]]. While death by other external causes, such as disease, accident, predation, and so forth, is common, it would occur naturally due to aging if such causes were absent. | + | An important distinction to make is that biological aging is not the same as the accumulation of [[disease]]s related to old age; ''disease'' is a blanket term used to describe a process within an organism that causes a decrease in its functional ability.<ref name=McDonald/> Aging is the natural and inevitable biological process that all [[animal]] life, including [[human being]]s, go through from conception through birth to [[death]]. While death by other external causes, such as disease, accident, predation, and so forth, is common, nonetheless death would occur naturally due to aging even in the absence of such causes. |

| | | | |

| | == Biological basis == | | == Biological basis == |

| − | The causes of aging are uncertain;<ref>{{Cite journal|last=Liochev|first=Stefan I.|date=2015-12-17|title=Which Is the Most Significant Cause of Aging?|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4712935/|journal=Antioxidants|volume=4|issue=4|pages=793–810|doi=10.3390/antiox4040793|issn=2076-3921|pmc=4712935|pmid=26783959}}</ref> current theories are assigned to the damage concept, whereby the accumulation of damage (such as [[DNA oxidation]]) may cause biological systems to fail, or to the programmed aging concept, whereby problems with the internal processes (epigenomic maintenance such as [[DNA methylation]]<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Ghosh|first1=Shampa|last2=Sinha|first2=Jitendra Kumar|last3=Raghunath|first3=Manchala|date=2016|title=Epigenomic maintenance through dietary intervention can facilitate DNA repair process to slow down the progress of premature aging|url=https://iubmb.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/iub.1532|journal=IUBMB Life|language=en|volume=68|issue=9|pages=717–721|doi=10.1002/iub.1532|pmid=27364681|issn=1521-6551|doi-access=free}}</ref>) may cause aging. Programmed aging should not be confused with programmed cell death ([[apoptosis]]). Additionally, there can be other reasons, which can speed up the rate of aging in organisms including human beings like obesity<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Ghosh|first1=Shampa|last2=Sinha|first2=Jitendra Kumar|last3=Raghunath|first3=Manchala|date=May 2019|title='Obesageing': Linking obesity & ageing|journal=The Indian Journal of Medical Research|volume=149|issue=5|pages=610–615|doi=10.4103/ijmr.IJMR_2120_18|issn=0971-5916|pmc=6702696|pmid=31417028}}</ref><ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Salvestrini|first1=Valentina|last2=Sell|first2=Christian|last3=Lorenzini|first3=Antonello|date=2019-05-03|title=Obesity May Accelerate the Aging Process|journal=Frontiers in Endocrinology|volume=10|page=266|doi=10.3389/fendo.2019.00266|issn=1664-2392|pmc=6509231|pmid=31130916}}</ref> and compromised [[immune system]]. | + | The causes of aging are uncertain, but appear to involve a number of factors.<ref>Stefan I. Liochev, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4712935/ Which Is the Most Significant Cause of Aging?] ''Antioxidants (Basel)'' 4(4) (December 2015): 793–810. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> The factors proposed to influence biological aging fall into two main categories: ''programmed'' and ''damage-related''. They are not necessarily mutually exclusive. |

| | | | |

| − | Researchers are only just beginning to understand the biological basis of aging even in relatively simple and short-lived organisms, such as [[yeast]].<ref name="Janssens 2015">{{cite journal | vauthors = Janssens GE, Meinema AC, González J, Wolters JC, Schmidt A, Guryev V, Bischoff R, Wit EC, Veenhoff LM, Heinemann M | display-authors = 6 | title = Protein biogenesis machinery is a driver of replicative aging in yeast | journal = eLife | volume = 4 | pages = e08527 | date = December 2015 | pmid = 26422514 | pmc = 4718733 | doi = 10.7554/eLife.08527 }}</ref> Less still is known of mammalian aging, in part due to the much longer lives of even small mammals such as the mouse (around 3 years). A [[model organism]] for studying of aging is the [[nematode]] ''[[Caenorhabditis elegans|C. elegans]]''. Thanks to its short lifespan of 2–3 weeks, our ability to easily perform genetic manipulations or to suppress gene activity with [[RNA interference]], or other factors.<ref name="RothmanSingson2012">{{cite book| vauthors = Wilkinson DS, Taylor RC, Dillin A | veditors = Rothman JH, Singson A | title = Caenorhabditis Elegans: Cell Biology and Physiology|chapter-url=https://books.google.com/books?id=F-jp8kwcHiAC|year=2012|publisher=Academic Press|isbn=978-0-12-394620-1|pages=353–81|chapter=Analysis of Aging in ''Caenorhabditis elegans''}}</ref> Most known mutations and RNA interference targets that extend lifespan were first discovered in ''C. elegans''.<ref name="Reis2009">{{cite journal | vauthors = Shmookler Reis RJ, Bharill P, Tazearslan C, Ayyadevara S | title = Extreme-longevity mutations orchestrate silencing of multiple signaling pathways | journal = Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects | volume = 1790 | issue = 10 | pages = 1075–83 | date = October 2009 | pmid = 19465083 | pmc = 2885961 | doi = 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.05.011 }}</ref>

| + | The first posits that aging is programmed and therefore follows an inexorable path, a biological timetable, perhaps one that might be a continuation of that which regulates childhood growth and development. This regulation would depend on changes in [[gene]] expression that affect the systems responsible for maintenance, repair, and defense responses. Programmed aging should not be confused with programmed cell death ([[apoptosis]]). |

| | | | |

| − | The factors proposed to influence biological aging<ref>{{cite web | title = Mitochondrial Theory of Aging and Other Aging Theories | publisher = 1Vigor | url = http://www.1vigor.com/science/mitochondrial-theory/ | access-date = 4 October 2013 }}</ref> fall into two main categories, ''programmed'' and ''damage-related''. Programmed factors follow a biological timetable, perhaps one that might be a continuation of the one that regulates childhood growth and development. This regulation would depend on changes in gene expression that affect the systems responsible for maintenance, repair and defense responses. Damage-related factors include internal and environmental assaults to living organisms that induce cumulative damage at various levels.<ref name="KunlinJin2010">{{cite journal | vauthors = Jin K | title = Modern Biological Theories of Aging | journal = Aging and Disease | volume = 1 | issue = 2 | pages = 72–74 | date = October 2010 | pmid = 21132086 | pmc = 2995895 }}</ref> A third, novel, concept is that aging is mediated by [[Virtuous circle and vicious circle|vicious cycles]].<ref name="Aleksey V 2018">{{cite journal | vauthors = Belikov AV | title = Age-related diseases as vicious cycles | journal = Ageing Research Reviews | volume = 49 | pages = 11–26 | date = January 2019 | pmid = 30458244 | doi = 10.1016/j.arr.2018.11.002 | s2cid = 53567141 }}</ref> | + | The second category of theories suggests various sources and targets of damage that lead to aging. Damage-related factors include internal and environmental assaults to living organisms that induce cumulative damage at various levels. |

| | | | |

| − | In a detailed review, Lopez-Otin and colleagues (2013), who discuss ageing through the lens of the damage theory, propose nine metabolic "hallmarks" of ageing in various organisms but especially mammals:<ref name="Lopez-Otin2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G | title = The hallmarks of aging | journal = Cell | volume = 153 | issue = 6 | pages = 1194–217 | date = June 2013 | pmid = 23746838 | pmc = 3836174 | doi = 10.1016/j.cell.2013.05.039 }}</ref>

| + | A third, novel concept is that aging is mediated by [[Virtuous circle and vicious circle|vicious cycles]].<ref>Aleksey V. Belikov, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30458244/ Age-related diseases as vicious cycles] ''Ageing Research Reviews'' 49 (January 2019): 11–26. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| − | * genomic instability (mutations accumulated in nuclear DNA, in mtDNA, and in the nuclear lamina)

| |

| − | * telomere attrition (the authors note that artificial telomerase confers non-cancerous immortality to otherwise mortal cells)

| |

| − | * epigenetic alterations (including DNA methylation patterns, post-translational modification of histones, and chromatin remodelling)

| |

| − | * loss of [[proteostasis]] (protein folding and proteolysis)

| |

| − | * deregulated nutrient sensing (relating to the [[Insulin-like growth factor 1#Aging|Growth hormone/Insulin-like growth factor 1 signalling pathway]], which is the most conserved ageing-controlling pathway in evolution and among its targets are the [[FOXO]]3/[[Sirtuin]] transcription factors and the [[mTOR]] complexes, probably responsive to [[caloric restriction]])

| |

| − | * mitochondrial dysfunction (the authors point out however that a causal link between ageing and increased mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species is no longer supported by recent research)

| |

| − | * cellular senescence (accumulation of no longer dividing cells in certain tissues, a process induced especially by [[P16|p16INK4a]]/Rb and p19ARF/[[p53]] to stop cancerous cells from proliferating)

| |

| − | * stem cell exhaustion (in the authors' view caused by damage factors such as those listed above)

| |

| − | * altered intercellular communication (encompassing especially inflammation but possibly also other intercellular interactions)

| |

| | | | |

| − | There are three main metabolic pathways which can influence the rate of ageing:

| + | Additionally, there can be other reasons which can speed up the rate of aging in organisms including human beings, such as obesity and compromised [[immune system]]. |

| − | * the [[FOXO3]]/[[Sirtuin]] pathway, probably responsive to [[caloric restriction]]

| |

| − | * the [[Insulin-like growth factor 1#Aging|Growth hormone/Insulin-like growth factor 1 signalling pathway]]

| |

| − | * the activity levels of the [[electron transport chain]] in mitochondria<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Berdyshev GD, Korotaev GK, Boiarskikh GV, Vaniushin BF | title = Molecular Biology of Aging | journal = Cell | volume = 96 | issue = 2 | pages = 347–62 | year = 2008 | pmid = 9988222 | doi = 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80567-x | publisher = Cold Spring Harbor | isbn = 978-0-87969-824-9 | s2cid = 17724023 }}</ref> and (in plants) in chloroplasts.

| |

| | | | |

| − | It is likely that most of these pathways affect ageing separately, because targeting them simultaneously leads to additive increases in lifespan.<ref name="Taylor2011">{{cite journal | vauthors = Taylor RC, Dillin A | title = Aging as an event of proteostasis collapse | journal = Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology | volume = 3 | issue = 5 | pages = a004440 | date = May 2011 | pmid = 21441594 | pmc = 3101847 | doi = 10.1101/cshperspect.a004440 }}</ref>

| + | ===Programmed factors=== |

| | + | The programmed approach suggests three major mechanisms which control aging:<ref name=Jin>Kunlin Jin, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2995895/ Modern Biological Theories of Aging] ''Aging Dis.'' 1(2) (October 2010): 72–74. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| | + | ;Programmed Longevity |

| | + | Aging is the result of a sequential switching on and off of certain [[gene]]s, with senescence being defined as the time when age-associated deficits are manifested. |

| | + | ;Endocrine Theory |

| | + | Biological clocks act through [[hormone]]s to control the pace of aging. |

| | + | ;Immunological Theory |

| | + | The [[immune system]] is programmed to decline over time, which leads to an increased vulnerability to infectious [[disease]]s and thus aging and death. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Programmed factors===

| + | The rate of aging varies substantially across different species, and this, to a large extent, is genetically based. For example, numerous [[perennial plant]]s ranging from [[strawberry|strawberries]] and [[potato]]es to [[willow]] trees typically produce [[clone]]s of themselves by [[vegetative reproduction]] and are thus potentially immortal, while [[annual plants]] such as [[wheat]] and [[watermelon]]s die each year and reproduce by sexual reproduction. The oldest [[animal]]s known so far are 15,000-year-old [[Antarctica|Antarctic]] [[sponge]]s,<ref>Marnie Chesterton, [https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-40224991 The oldest living thing on Earth] ''BBC News'', June 12, 2017. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> which can reproduce both sexually and clonally. |

| − | The rate of ageing varies substantially across different species, and this, to a large extent, is genetically based. For example, numerous [[perennial plant]]s ranging from strawberries and potatoes to [[Willow#Cultivation|willow trees]] typically produce clones of themselves by [[vegetative reproduction]] and are thus potentially immortal, while [[annual plants]] such as wheat and watermelons die each year and reproduce by sexual reproduction. In 2008 it was discovered that inactivation of only two genes in the annual plant ''Arabidopsis thaliana'' leads to its conversion into a potentially immortal perennial plant.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Melzer S, Lens F, Gennen J, Vanneste S, Rohde A, Beeckman T | title = Flowering-time genes modulate meristem determinacy and growth form in Arabidopsis thaliana | journal = Nature Genetics | volume = 40 | issue = 12 | pages = 1489–92 | date = December 2008 | pmid = 18997783 | doi = 10.1038/ng.253 | url = http://www.repository.naturalis.nl/record/429531 | s2cid = 13225884 }}</ref> The oldest animals known so far are 15,000-year-old Antarctic [[sponge]]s,<ref name=BBC2017-OldestLivingThing>{{Cite news|last1=Chesterton|first1=Marnie| name-list-style = vanc |title=The oldest living thing on Earth|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-40224991|access-date=16 September 2017|date=12 June 2017|work=BBC News}}</ref> which can reproduce both sexually and clonally. | |

| | | | |

| − | Clonal immortality apart, there are certain species whose individual lifespans stand out among Earth's life-forms, including the [[bristlecone pine]] at 5062 years<ref name=oldest>{{cite web|url=http://www.rmtrr.org/oldlist.htm|title=Oldlist|publisher=Rocky Mountain Tree Ring Research|access-date=2016-08-12}}</ref> or 5067 years,<ref name=BBC2017-OldestLivingThing/> invertebrates like the [[hard clam]] (known as ''quahog'' in New England) at 508 years,<ref name="Sosnowska2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Sosnowska D, Richardson C, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Ridgway I | title = A heart that beats for 500 years: age-related changes in cardiac proteasome activity, oxidative protein damage and expression of heat shock proteins, inflammatory factors, and mitochondrial complexes in Arctica islandica, the longest-living noncolonial animal | journal = The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences | volume = 69 | issue = 12 | pages = 1448–61 | date = December 2014 | pmid = 24347613 | pmc = 4271020 | doi = 10.1093/gerona/glt201 }}</ref> the [[Greenland shark]] at 400 years,<ref name="Nielsen2016">{{cite journal | vauthors = Nielsen J, Hedeholm RB, Heinemeier J, Bushnell PG, Christiansen JS, Olsen J, Ramsey CB, Brill RW, Simon M, Steffensen KF, Steffensen JF | display-authors = 6 | title = Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) | journal = Science | volume = 353 | issue = 6300 | pages = 702–4 | date = August 2016 | pmid = 27516602 | doi = 10.1126/science.aaf1703 | url = https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:6c040460-9519-4720-9669-9911bdd03b09 | s2cid = 206647043 | bibcode = 2016Sci...353..702N }}</ref> various deep-sea [[tube worms]] at over 300 years,<ref name="Durkin2017">{{cite journal | vauthors = Durkin A, Fisher CR, Cordes EE | title = Extreme longevity in a deep-sea vestimentiferan tubeworm and its implications for the evolution of life history strategies | journal = Die Naturwissenschaften | volume = 104 | issue = 7–8 | pages = 63 | date = August 2017 | pmid = 28689349 | doi = 10.1007/s00114-017-1479-z | s2cid = 11287549 | bibcode = 2017SciNa.104...63D }}</ref> fish like the [[sturgeon]] and the [[Sebastes|rockfish]], and the [[sea anemone]]<ref>Timiras, Paola S. (2003) ''Physiological Basis of Ageing and Geriatrics''. Informa Health Care. {{ISBN|0-8493-0948-4}}. p. 26.</ref> and [[lobster]].<ref>{{cite web |url=http://animals.howstuffworks.com/marine-life/400-pound-lobster.htm/printable |title=Is there a 400 pound lobster out there? | vauthors = Silverman J |publisher=[[howstuffworks]]|date=2007-07-05 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book |title=Consider the Lobster and Other Essays | vauthors = Wallace DF |publisher=[[Little, Brown & Company]] |year=2005 |isbn=978-0-316-15611-0|title-link=Consider the Lobster }}{{page needed|date=November 2013}}</ref> Such organisms are sometimes said to exhibit [[negligible senescence]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Guerin JC | title = Emerging area of aging research: long-lived animals with "negligible senescence" | journal = Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences | volume = 1019 | issue = 1 | pages = 518–20 | date = June 2004 | pmid = 15247078 | doi = 10.1196/annals.1297.096 | bibcode = 2004NYASA1019..518G | s2cid = 6418634 }}</ref> The genetic aspect has also been demonstrated in studies of human [[Research into centenarians|centenarians]]. | + | Clonal immortality apart, there are certain species whose individual lifespans stand out among Earth's life-forms, including the [[bristlecone pine]] at around 5,000 years<ref>[http://www.rmtrr.org/oldlist.htm Oldlist] ''Rocky Mountain Tree Ring Research''. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> invertebrates like the [[hard clam]] (known as ''quahog'' in New England) at 508 years,<ref>Danuta Sosnowska, Chris Richardson, William E. Sonntag, Anna Csiszar, Zoltan Ungvari, and Iain Ridgway, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4271020/ A heart that beats for 500 years] ''The Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences'' 69(12) (December 2014): 1448–1461. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> the [[Greenland shark]] at 400 years,<ref>J. Nielsen, ''et al'', [https://ora.ox.ac.uk/objects/uuid:6c040460-9519-4720-9669-9911bdd03b09 Eye lens radiocarbon reveals centuries of longevity in the Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus)] ''Science'' 353(6300) (August 2016): 702–704. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> various deep-sea [[tube worms]] at over 300 years,<ref>Alanna Durkin, Charles R. Fisher, Erik E. Cordes, [https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00114-017-1479-z Extreme longevity in a deep-sea vestimentiferan tubeworm and its implications for the evolution of life history strategies] ''The Science of Nature'' 104(7–8) (August 2017): 63. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> and [[lobster]]s.<ref>Jacob Silverman, [https://animals.howstuffworks.com/marine-life/400-pound-lobster.htm Is there a 400 pound lobster out there?] ''How Stuff Works''. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> Such organisms are sometimes said to exhibit [[negligible senescence]].<ref>John C. Guerin, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15247078/ Emerging area of aging research: long-lived animals with "negligible senescence"] ''Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences'' 1019(1) (June 2004): 518–520. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> |

| | | | |

| − | * [[Evolution of aging|Evolution of ageing]]: Many have argued that life span, like other [[phenotypes]], is [[natural selection|selected]]. Traits that benefit early survival and reproduction will be [[natural selection|selected]] for even if they contribute to an earlier death. Such a genetic effect is called the [[Antagonistic pleiotropy hypothesis|antagonistic pleiotropy]] effect when referring to a gene (pleiotropy signifying the gene has a double function – enabling reproduction at a young age but costing the organism life expectancy in old age) and is called the [[Evolution of aging|disposable soma]] effect when referring to an entire genetic programme (the organism diverting limited resources from maintenance to reproduction).<ref name="Williams1957"/> The biological mechanisms which regulate lifespan evolved several hundred million years ago.<ref name="Reis2009" />

| + | [[File:Habibaadansalat.jpg|thumb|right|350px|An elderly [[Somali people|Somali]] woman]] |

| − | ** Some evidence is provided by oxygen-deprived bacterial cultures.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Nyström T | title = The free-radical hypothesis of aging goes prokaryotic | journal = Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences | volume = 60 | issue = 7 | pages = 1333–41 | date = July 2003 | pmid = 12943222 | doi = 10.1007/s00018-003-2310-X | s2cid = 8406111 }}</ref>

| |

| − | ** The theory would explain why the [[Dominance (genetics)|autosomal dominant]] disease, [[Huntington's disease]], can persist even though it is inexorably lethal. Also, it has been suggested that some of the genetic variants that increase fertility in the young increase cancer risk in the old. Such variants occur in genes p53<ref name="Kang 2009">{{cite journal | vauthors = Kang HJ, Feng Z, Sun Y, Atwal G, Murphy ME, Rebbeck TR, Rosenwaks Z, Levine AJ, Hu W | display-authors = 6 | title = Single-nucleotide polymorphisms in the p53 pathway regulate fertility in humans | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 106 | issue = 24 | pages = 9761–6 | date = June 2009 | pmid = 19470478 | pmc = 2700980 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.0904280106 | bibcode = 2009PNAS..106.9761K }}</ref> and BRCA1.<ref name="Smith 2012">{{cite journal | vauthors = Smith KR, Hanson HA, Mineau GP, Buys SS | title = Effects of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations on female fertility | journal = Proceedings. Biological Sciences | volume = 279 | issue = 1732 | pages = 1389–95 | date = April 2012 | pmid = 21993507 | pmc = 3282366 | doi = 10.1098/rspb.2011.1697 }}</ref>

| |

| − | ** The [[reproductive-cell cycle theory]] argues that ageing is regulated specifically by reproductive hormones that act in an antagonistic [[pleiotropic]] manner via cell cycle signalling, promoting growth and development early in life to achieve reproduction, but becoming dysregulated later in life, driving senescence (dyosis) in a futile attempt to maintain reproductive ability.<ref name="Bowen 2004">{{cite journal | vauthors = Bowen RL, Atwood CS | title = Living and dying for sex. A theory of aging based on the modulation of cell cycle signaling by reproductive hormones | journal = Gerontology | volume = 50 | issue = 5 | pages = 265–90 | year = 2004 | pmid = 15331856 | doi = 10.1159/000079125 | s2cid = 18109386 }}</ref><ref name="pmid20851172">{{cite journal | vauthors = Atwood CS, Bowen RL | title = The reproductive-cell cycle theory of aging: an update | journal = Experimental Gerontology | volume = 46 | issue = 2–3 | pages = 100–7 | year = 2011 | pmid = 20851172 | doi = 10.1016/j.exger.2010.09.007 | s2cid = 20998909 }}</ref> The endocrine dyscrasia that follows the loss of follicles with menopause, and the loss of Leydig and Sertoli cells during andropause, drive aberrant cell cycle signalling that leads to cell death and dysfunction, tissue dysfunction (disease) and ultimately death. Moreover, the hormones that regulate reproduction also regulate cellular metabolism, explaining the increases in fat deposition during pregnancy through to the deposition of centralised adiposity with the dysregulation of the HPG axis following menopause and during andropause (Atwood and Bowen, 2004). This theory, which introduced a new definition of ageing, has facilitated the conceptualisation of why and how ageing occurs at the evolutionary, physiological and molecular levels.<ref name="Bowen 2004"/>

| |

| − | * Autoimmunity: The idea that ageing results from an increase in [[autoantibodies]] that attack the body's tissues. A number of diseases associated with ageing, such as [[atrophic gastritis]] and [[Hashimoto's thyroiditis]], are probably autoimmune in this way. However, while inflammation is very much evident in old mammals, even completely [[Severe combined immunodeficiency#SCID in animals|immunodeficient]] mice raised in [[Specific-pathogen-free|pathogen-free]] laboratory conditions still experience senescence.{{citation needed|date=August 2016}}

| |

| − | [[File:Habibaadansalat.jpg|thumb|right|300px|An elderly [[Somali people|Somali]] woman]] | |

| − | * The cellular balance between energy generation and consumption (energy homeostasis) requires tight regulation during ageing. In 2011, it was demonstrated that acetylation levels of [[AMP-activated protein kinase]] change with age in yeast and that preventing this change slows yeast ageing.<ref name="Mair2011">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mair W, Steffen KK, Dillin A | title = SIP-ing the elixir of youth | journal = Cell | volume = 146 | issue = 6 | pages = 859–60 | date = September 2011 | pmid = 21925309 | doi = 10.1016/j.cell.2011.08.026 | doi-access = free }}</ref>

| |

| − | * Skin ageing is caused in part by [[TGF-β]], which reduces the subcutaneous fat that gives skin a pleasant appearance and texture. [[TGF-β]] does this by blocking the conversion of [[dermal fibroblasts]] into [[fat cells]]; with fewer fat cells underneath to provide support, the skin becomes saggy and wrinkled. Subcutaneous fat also produces [[cathelicidin]], which is a [[peptide]] that fights bacterial infections.<ref>{{Cite press release |title = UC San Diego Researchers Identify How Skin Ages, Loses Fat and Immunity |url = https://ucsdnews.ucsd.edu/pressrelease/uc_san_diego_researchers_identify_how_skin_ages_loses_fat_and_immunity |date = 2018-12-26 |first = Yadira | last = Galindo | publisher = University of California San Diego}}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Zhang LJ, Chen SX, Guerrero-Juarez CF, Li F, Tong Y, Liang Y, Liggins M, Chen X, Chen H, Li M, Hata T, Zheng Y, Plikus MV, Gallo RL | display-authors = 6 | title = Age-Related Loss of Innate Immune Antimicrobial Function of Dermal Fat Is Mediated by Transforming Growth Factor Beta | journal = Immunity | volume = 50 | issue = 1 | pages = 121–136.e5 | date = January 2019 | pmid = 30594464 | pmc = 7191997 | doi = 10.1016/j.immuni.2018.11.003 | url = | doi-access = free }}</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| | ===Damage-related factors=== | | ===Damage-related factors=== |

| − | * [[DNA damage theory of aging|DNA damage theory of ageing]]: DNA damage is thought to be the common basis of both cancer and ageing, and it has been argued that intrinsic causes of [[DNA damage (naturally occurring)|DNA damage]] are the most important drivers of ageing.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Gensler HL, Bernstein H | title = DNA damage as the primary cause of aging | journal = The Quarterly Review of Biology | volume = 56 | issue = 3 | pages = 279–303 | date = September 1981 | pmid = 7031747 | doi = 10.1086/412317 | jstor = 2826464 | s2cid = 20822805 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sinha JK, Ghosh S, Swain U, Giridharan NV, Raghunath M | title = Increased macromolecular damage due to oxidative stress in the neocortex and hippocampus of WNIN/Ob, a novel rat model of premature aging | journal = Neuroscience | volume = 269 | pages = 256–64 | date = June 2014 | pmid = 24709042 | doi = 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2014.03.040 | s2cid = 9934178 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Freitas AA, de Magalhães JP | title = A review and appraisal of the DNA damage theory of ageing | journal = Mutation Research | volume = 728 | issue = 1–2 | pages = 12–22 | year = 2011 | pmid = 21600302 | doi = 10.1016/j.mrrev.2011.05.001 }}</ref> Genetic damage (aberrant structural alterations of the DNA), [[mutation]]s (changes in the DNA sequence), and epimutations ([[Cancer epigenetics#DNA methylation|methylation of gene promoter regions]] or alterations of the [[Cancer epigenetics#Histone modification|DNA scaffolding]] which [[Regulation of gene expression|regulate gene expression]]), can cause abnormal gene expression. DNA damage causes the cells to stop dividing or induces [[apoptosis]], often [[Stem cell theory of aging|affecting stem cell pools]] and hence hindering regeneration. However, lifelong studies of mice suggest that most mutations happen during embryonic and childhood development, when cells divide often, as each cell division is a chance for errors in DNA replication.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Robert L, Labat-Robert J, Robert AM | title = Genetic, epigenetic and posttranslational mechanisms of aging | journal = Biogerontology | volume = 11 | issue = 4 | pages = 387–99 | date = August 2010 | pmid = 20157779 | doi = 10.1007/s10522-010-9262-y | s2cid = 21455794 }}</ref>

| + | Numerous damage-related factors have been proposed that lead to aging, including the following:<ref name=Jin/> |

| − | * [[Genetic instability]]: Dogs annually lose approximately 3.3% of the DNA in their heart muscle cells while humans lose approximately 0.6% of their heart muscle DNA each year. These numbers are close to the ratio of the maximum longevities of the two species (120 years vs. 20 years, a 6/1 ratio). The comparative percentage is also similar between the dog and human for yearly DNA loss in the brain and lymphocytes. As stated by lead author, [[Bernard L. Strehler]], "... genetic damage (particularly gene loss) is almost certainly (or probably the) central cause of ageing."<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Strehler BL | title = Genetic instability as the primary cause of human aging | journal = Experimental Gerontology | volume = 21 | issue = 4–5 | pages = 283–319 | year = 1986 | pmid = 3545872 | doi = 10.1016/0531-5565(86)90038-0 | s2cid = 34431271 }}</ref>

| + | ;Wear and tear theory |

| − | * Accumulation of waste:

| + | Cells and tissues have vital parts that wear out resulting in aging. Like components of an aging machine, parts of the body eventually wear out from repeated use, leading to cell death and inability to function. |

| − | ** A buildup of waste products in cells presumably interferes with metabolism. For example, a waste product called [[lipofuscin]] is formed by a complex reaction in cells that binds fat to proteins. This waste accumulates in the cells as small granules, which increase in size as a person ages.<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Gavrilov LA, Gavrilova NA | date = 2006 | chapter = Reliability Theory of Aging and Longevity | pages = 3–42 | title = Handbook of the Biology of Aging | veditors = Masoro EJ, Austad SN | publisher = Academic Press | location = San Diego, CA }}</ref>

| |

| − | ** The hallmark of ageing yeast cells appears to be overproduction of certain proteins.<ref name="Janssens 2015"/>

| |

| − | ** [[Autophagy]] induction can enhance clearance of toxic intracellular waste associated with neurodegenerative diseases and has been comprehensively demonstrated to improve lifespan in yeast, worms, flies, rodents and primates. The situation, however, has been complicated by the identification that autophagy up-regulation can also occur during ageing.<ref name="Carroll 2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Carroll B, Hewitt G, Korolchuk VI | title = Autophagy and ageing: implications for age-related neurodegenerative diseases | journal = Essays in Biochemistry | volume = 55 | pages = 119–31 | year = 2013 | pmid = 24070476 | doi = 10.1042/bse0550119 | s2cid = 1603760 }}</ref> Autophagy is enhanced in obese mice by caloric restriction, exercise, and a low fat diet (but in these mice is evidently not related with the activation of [[AMP-activated protein kinase]], see above).<ref name="Cui 2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Cui M, Yu H, Wang J, Gao J, Li J | title = Chronic caloric restriction and exercise improve metabolic conditions of dietary-induced obese mice in autophagy correlated manner without involving AMPK | journal = Journal of Diabetes Research | volume = 2013 | pages = 852754 | year = 2013 | pmid = 23762877 | pmc = 3671310 | doi = 10.1155/2013/852754 }}</ref>

| |

| − | * Wear-and-tear theory: The very general idea that changes associated with ageing are the result of chance damage that accumulates over time.<ref name="KunlinJin2010"/>

| |

| − | * Accumulation of errors: The idea that ageing results from chance events that escape proof reading mechanisms, which gradually damages the genetic code.

| |

| − | * [[Heterochromatin]] loss, model of ageing.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lee JH, Kim EW, Croteau DL, Bohr VA | title = Heterochromatin: an epigenetic point of view in aging | journal = Experimental & Molecular Medicine | pages = 1466–1474 | date = September 2020 | volume = 52 | issue = 9 | pmid = 32887933 | doi = 10.1038/s12276-020-00497-4 | url = https://www.nature.com/articles/s12276-020-00497-4 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Villeponteau B | title = The heterochromatin loss model of aging | journal = Experimental Gerontology | volume = 32 | issue = 4–5 | pages = 383–94 | date = 1997-07-01 | pmid = 9315443 | doi = 10.1016/S0531-5565(96)00155-6 | url = http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0531556596001556 | series = Proceedings of the Third International Symposium on the Neurobiology and Neuroendocrinology of Aging | s2cid = 29375335 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Tsurumi A, Li WX | title = Global heterochromatin loss: a unifying theory of aging? | journal = Epigenetics | volume = 7 | issue = 7 | pages = 680–8 | date = July 2012 | pmid = 22647267 | pmc = 3414389 | doi = 10.4161/epi.20540 }}</ref>

| |

| − | * [[Transposable elements]] in genome disintegration as the primary role in the mechanism of ageing.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sturm Á, Ivics Z, Vellai T | title = The mechanism of ageing: primary role of transposable elements in genome disintegration | journal = Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences | volume = 72 | issue = 10 | pages = 1839–47 | date = May 2015 | pmid = 25837999 | doi = 10.1007/s00018-015-1896-0 | s2cid = 13241098 | doi-access = free }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Elsner D, Meusemann K, Korb J | title = Longevity and transposon defense, the case of termite reproductives | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 115 | issue = 21 | pages = 5504–5509 | date = May 2018 | pmid = 29735660 | pmc = 6003524 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.1804046115 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Sturm Á, Perczel A, Ivics Z, Vellai T | title = The Piwi-piRNA pathway: road to immortality | journal = Aging Cell | volume = 16 | issue = 5 | pages = 906–911 | date = October 2017 | pmid = 28653810 | pmc = 5595689 | doi = 10.1111/acel.12630 }}</ref>

| |

| − | * Cross-linkage: The idea that ageing results from accumulation of [[cross-linked]] compounds that interfere with normal cell function.<ref name="Bernstein book" /><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Bjorksten J, Tenhu H | title = The crosslinking theory of aging—added evidence | journal = Experimental Gerontology | volume = 25 | issue = 2 | pages = 91–5 | year = 1990 | pmid = 2115005 | doi = 10.1016/0531-5565(90)90039-5 | s2cid = 19115146 }}</ref>

| |

| − | * Studies of mtDNA mutator mice have shown that increased levels of somatic mtDNA mutations directly can cause a variety of ageing phenotypes. The authors propose that mtDNA mutations lead to respiratory-chain-deficient cells and thence to apoptosis and cell loss. They cast doubt experimentally however on the common assumption that mitochondrial mutations and dysfunction lead to increased generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Trifunovic A, Larsson NG | title = Mitochondrial dysfunction as a cause of ageing | journal = Journal of Internal Medicine | volume = 263 | issue = 2 | pages = 167–78 | date = February 2008 | pmid = 18226094 | doi = 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2007.01905.x | s2cid = 28396237 | doi-access = free }}</ref>

| |

| − | * [[Free-radical theory]]: Damage by [[free radical]]s, or more generally [[reactive oxygen species]] or [[oxidative stress]], create damage that may give rise to the symptoms we recognise as ageing.<ref name="Bernstein book" /><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Harman D | title = The aging process | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 78 | issue = 11 | pages = 7124–8 | date = November 1981 | pmid = 6947277 | pmc = 349208 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.78.11.7124 | bibcode = 1981PNAS...78.7124H }}</ref> [[Michael Ristow]]'s group has provided evidence that the effect of calorie restriction may be due to increased formation of [[free radicals]] within the [[mitochondria]], causing a secondary induction of increased [[antioxidant]] defence capacity.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Schulz TJ, Zarse K, Voigt A, Urban N, Birringer M, Ristow M | title = Glucose restriction extends Caenorhabditis elegans life span by inducing mitochondrial respiration and increasing oxidative stress | journal = Cell Metabolism | volume = 6 | issue = 4 | pages = 280–93 | date = October 2007 | pmid = 17908557 | doi = 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.08.011 }}</ref>

| |

| − | *[[Mitochondrial theory of ageing]]: [[free radicals]] produced by [[mitochondria]]l activity damage cellular components, leading to ageing.

| |

| − | * [[8-Oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine|DNA oxidation]] and caloric restriction: Caloric restriction reduces [[8-Oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine|8-OH-dG]] DNA damage in organs of ageing rats and mice.<ref name="pmid11517304">{{cite journal | vauthors = Hamilton ML, Van Remmen H, Drake JA, Yang H, Guo ZM, Kewitt K, Walter CA, Richardson A | display-authors = 6 | title = Does oxidative damage to DNA increase with age? | journal = Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America | volume = 98 | issue = 18 | pages = 10469–74 | date = August 2001 | pmid = 11517304 | pmc = 56984 | doi = 10.1073/pnas.171202698 | bibcode = 2001PNAS...9810469H }}</ref><ref name="pmid15763395">{{cite journal | vauthors = Wolf FI, Fasanella S, Tedesco B, Cavallini G, Donati A, Bergamini E, Cittadini A | title = Peripheral lymphocyte 8-OHdG levels correlate with age-associated increase of tissue oxidative DNA damage in Sprague-Dawley rats. Protective effects of caloric restriction | journal = Experimental Gerontology | volume = 40 | issue = 3 | pages = 181–8 | date = March 2005 | pmid = 15763395 | doi = 10.1016/j.exger.2004.11.002 | s2cid = 23752647 }}</ref> Thus, reduction of oxidative DNA damage is associated with a slower rate of ageing and increased lifespan.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Anson RM, Bohr VA | title = Mitochondria, oxidative DNA damage, and aging | journal = Journal of the American Aging Association | volume = 23 | issue = 4 | pages = 199–218 | date = October 2000 | pmid = 23604866 | pmc = 3455271 | doi = 10.1007/s11357-000-0020-y }}</ref> In a 2021 review article, Vijg stated that “Based on an abundance of evidence, [[DNA damage (naturally occurring)|DNA damage]] is now considered as the single most important driver of the degenerative processes that collectively cause aging.”<ref>Vijg J. From DNA damage to mutations: All roads lead to aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2021 Mar 9;68:101316. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2021.101316. Epub ahead of print. PMID 33711511</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | == Effects ==

| + | ;Rate of living theory |

| − | [[File:Senescence.JPG|thumb|300px|Enlarged ears and noses of old humans are sometimes blamed on continual cartilage growth, but the cause is more probably gravity.<ref name=Guardian2013>{{Cite news|title=Big ears: they really do grow as we age |url=https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/shortcuts/2013/jul/17/big-ears-grow-as-we-age|access-date=9 September 2016|date=July 2013|id=MeshID:D000375; OMIM:502000| vauthors = Moss S |newspaper=The Guardian}}</ref>]] | + | This suggests that the greater an organism’s rate of [[oxygen]] basal [[metabolism]], the shorter its life span. While helpful, this does not explain maximum life span. |

| | + | |

| | + | ;Cross-linking theory |

| | + | According to this theory, an accumulation of cross-linked [[protein]]s damages cells and tissues, slowing down bodily processes and resulting in aging. |

| | | | |

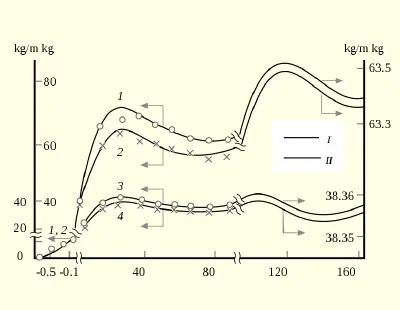

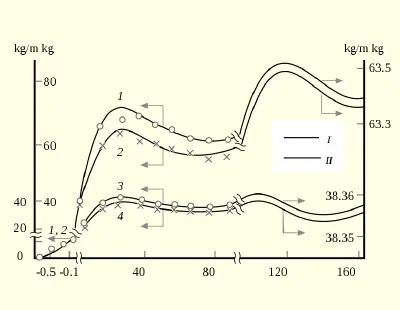

| − | [[File: Age dynamics of the body mass.png|thumb|400px|Age dynamics of the body mass (1, 2) and mass normalized to height (3, 4) of men (1, 3) and women (2, 4).<ref name="Age dynamics">{{cite journal| vauthors = Gerasimov IG, Ignatov DY |title=Age Dynamics of Body Mass and Human Lifespan| journal = Journal of Evolutionary Biochemistry and Physiology | volume = 40 | issue = 3| pages = 343–349|year=2004| doi = 10.1023/B:JOEY.0000042639.72529.e1|s2cid=9070790|url=https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226729610}}</ref>]] | + | ;Free radical theory |

| | + | This proposes that [[free radical]]s cause damage to the macromolecular components of the cell, giving rise to accumulated damage causing cells, and eventually organs, to stop functioning. Macromolecules, such as [[nucleic acid]]s, [[lipid]]s, [[sugar]]s, and [[proteins]], are susceptible to free radical attack. [[Enzyme]]s, which are natural antioxidants, are found in the body and function to curb build-up of free radicals. |

| | | | |

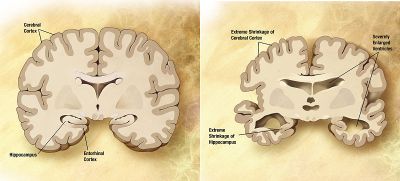

| − | [[File:Alzheimer's disease brain comparison.jpg|thumb|400px|Comparison of a normal aged brain (left) and a brain affected by [[Alzheimer's disease]] (right).]] | + | ;Somatic DNA damage theory |

| − | Ageing increases the [[risk factor|risk]] of [[diseas]]es.

| + | [[DNA]] damage occurs continuously in cells of living organisms. While most of the damage is repaired naturally, some accumulates as the repair mechanisms cannot correct defects as fast as they are produced. Thus, aging results from damage to the genetic integrity of the body’s cells. |

| | | | |

| − | A number of characteristic ageing symptoms are experienced by a majority or by a significant proportion of humans during their lifetimes.

| + | Other suggested factors include: progressive loss of physiological integrity through genomic instability (mutations accumulated in nuclear DNA, in mtDNA, and in the nuclear lamina) and [[telomere]] attrition.<ref>Carlos López-Otín, Maria A. Blasco, Linda Partridge, Manuel Serrano, and Guido Kroemer, [https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3836174/ The Hallmarks of Aging] ''Cell'' 153(6) (June 2013): 1194–1217. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> Also, accumulation of waste products in cells presumably interferes with [[metabolism]]. For example, a waste product called [[lipofuscin]] is formed by a complex reaction in cells that binds fat to proteins. This waste accumulates in the cells as small granules, which increase in size as a person ages.<ref> Edward J. Masoro and Steven N. Austad (eds.), ''Handbook of the Biology of Aging'' (Academic Press, 2006, ISBN 0120883872).</ref> |

| − | * Teenagers lose the young child's ability to [[Presbycusis|hear]] high-frequency sounds above 20 kHz.<ref name=HiFreqAudiometry2014>{{cite journal | vauthors = Rodríguez Valiente A, Trinidad A, García Berrocal JR, Górriz C, Ramírez Camacho R | title = Extended high-frequency (9-20 kHz) audiometry reference thresholds in 645 healthy subjects | journal = International Journal of Audiology | volume = 53 | issue = 8 | pages = 531–45 | date = August 2014 | pmid = 24749665 | doi = 10.3109/14992027.2014.893375 | s2cid = 30960789 }}</ref>

| |

| − | * [[Wrinkle]]s develop mainly due to [[photoaging|photoageing]], particularly affecting sun-exposed areas (face).<ref name="Thurstan 2012">{{cite journal | vauthors = Thurstan SA, Gibbs NK, Langton AK, Griffiths CE, Watson RE, Sherratt MJ | title = Chemical consequences of cutaneous photoageing | journal = Chemistry Central Journal | volume = 6 | issue = 1 | pages = 34 | date = April 2012 | pmid = 22534143 | pmc = 3410765 | doi = 10.1186/1752-153X-6-34 }}</ref>

| |

| − | * After [[Age and female fertility|peaking in the mid-20s, female fertility]] declines.<ref>{{cite journal|url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0076677/|title=Infertility: Overview|last=pmhdev|date=25 March 2015|publisher=Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG)|via=www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov}}</ref>

| |

| − | * After age 30 the mass of human body is decreased until 70 years and then shows damping oscillations.<ref name="Age dynamics"/>

| |

| − | * Muscles have reduced capacity of responding to exercise or injury and loss of muscle mass and strength ([[sarcopenia]]) is common.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Ryall JG, Schertzer JD, Lynch GS | title = Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and weakness | journal = Biogerontology | volume = 9 | issue = 4 | pages = 213–28 | date = August 2008 | pmid = 18299960 | doi = 10.1007/s10522-008-9131-0 | s2cid = 8576449 }}</ref> VO2 max and maximum heart rate decline.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Betik AC, Hepple RT | title = Determinants of VO2 max decline with aging: an integrated perspective | journal = Applied Physiology, Nutrition, and Metabolism | volume = 33 | issue = 1 | pages = 130–40 | date = February 2008 | pmid = 18347663 | doi = 10.1139/H07-174 | s2cid = 24468921 }}</ref>

| |

| − | *Hand strength and mobility are decreased during the aging process. These things include, "hand and finger strength and ability to control submaximal pinch force and maintain a steady precision pinch posture, manual speed, and hand sensation"<ref>{{Cite journal|last1=Ranganathan|first1=Vinoth K.|last2=Siemionow|first2=Vlodek|last3=Sahgal|first3=Vinod|last4=Yue|first4=Guang H.|date=November 2001|title=Effects of Aging on Hand Function|url=http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911240.x|journal=Journal of the American Geriatrics Society|volume=49|issue=11|pages=1478–1484|doi=10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911240.x|pmid=11890586|s2cid=22988219|issn=0002-8614}}</ref>

| |

| − | * People over 35 years of age are at increasing risk for losing strength in the [[ciliary muscle]] of the eyes which leads to difficulty focusing on close objects, or [[presbyopia]].<ref>{{cite web|title=Facts About Presbyopia|url=https://nei.nih.gov/health/errors/presbyopia|publisher=National Eye Institute|access-date=11 September 2016|location=Last Reviewed October 2010}}</ref><ref name="Weale 2003">{{cite journal | vauthors = Weale RA | title = Epidemiology of refractive errors and presbyopia | journal = Survey of Ophthalmology | volume = 48 | issue = 5 | pages = 515–43 | year = 2003 | pmid = 14499819 | doi = 10.1016/S0039-6257(03)00086-9 }}</ref> Most people experience [[presbyopia]] by age 45–50.<ref name="Truscott 2009">{{cite journal | vauthors = Truscott RJ | title = Presbyopia. Emerging from a blur towards an understanding of the molecular basis for this most common eye condition | journal = Experimental Eye Research | volume = 88 | issue = 2 | pages = 241–7 | date = February 2009 | pmid = 18675268 | doi = 10.1016/j.exer.2008.07.003 }}</ref> The cause is lens hardening by decreasing levels of [[alpha-crystallin]], a process which may be sped up by higher temperatures.<ref name="Truscott 2009"/><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Pathai S, Shiels PG, Lawn SD, Cook C, Gilbert C | title = The eye as a model of ageing in translational research—molecular, epigenetic and clinical aspects | journal = Ageing Research Reviews | volume = 12 | issue = 2 | pages = 490–508 | date = March 2013 | pmid = 23274270 | doi = 10.1016/j.arr.2012.11.002 | s2cid = 26015190 }}</ref>

| |

| − | * Around age 50, [[Human hair color#Aging or achromotrichia|hair turns grey]].<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Pandhi D, Khanna D | title = Premature graying of hair | journal = Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology and Leprology | volume = 79 | issue = 5 | pages = 641–53 | date = 2013 | pmid = 23974581 | doi = 10.4103/0378-6323.116733 | doi-access = free }}</ref> [[Pattern hair loss]] by the age of 50 affects about 30–50% of males<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Hamilton JB | title = Patterned loss of hair in man; types and incidence | journal = Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences | volume = 53 | issue = 3 | pages = 708–28 | date = March 1951 | pmid = 14819896 | doi = 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1951.tb31971.x | bibcode = 1951NYASA..53..708H | s2cid = 32685699 }}</ref> and a quarter of females.<ref name=Var2015>{{cite journal | vauthors = Vary JC | title = Selected Disorders of Skin Appendages—Acne, Alopecia, Hyperhidrosis | journal = The Medical Clinics of North America | volume = 99 | issue = 6 | pages = 1195–211 | date = November 2015 | pmid = 26476248 | doi = 10.1016/j.mcna.2015.07.003 }}</ref>

| |

| − | * [[Menopause]] typically occurs between 44 and 58 years of age.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Morabia A, Costanza MC | title = International variability in ages at menarche, first livebirth, and menopause. World Health Organization Collaborative Study of Neoplasia and Steroid Contraceptives | journal = American Journal of Epidemiology | volume = 148 | issue = 12 | pages = 1195–205 | date = December 1998 | pmid = 9867266 | doi = 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009609 | doi-access = free }}</ref>

| |

| − | * In the 60–64 age cohort, the incidence of [[osteoarthritis]] rises to 53%. Only 20% however report disabling osteoarthritis at this age.<ref name="Thomas2014">{{cite journal | vauthors = Thomas E, Peat G, Croft P | title = Defining and mapping the person with osteoarthritis for population studies and public health | journal = Rheumatology | volume = 53 | issue = 2 | pages = 338–45 | date = February 2014 | pmid = 24173433 | pmc = 3894672 | doi = 10.1093/rheumatology/ket346 }}</ref>

| |

| − | * Almost half of people older than 75 have [[hearing loss]] (presbycusis) inhibiting spoken communication.<ref>{{cite web|title=Hearing Loss and Older Adults|url=https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/hearing-loss-older-adults|publisher=National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders|access-date=11 September 2016|format=Last Updated 3 June 2016|date=2016-01-26}}</ref> Many vertebrates such as fish, birds and amphibians do not suffer presbycusis in old age as they are able to regenerate their [[cochlea]]r sensory cells, whereas mammals including humans have genetically lost this ability.<ref name="Rubel2013">{{cite journal | vauthors = Rubel EW, Furrer SA, Stone JS | title = A brief history of hair cell regeneration research and speculations on the future | journal = Hearing Research | volume = 297 | pages = 42–51 | date = March 2013 | pmid = 23321648 | pmc = 3657556 | doi = 10.1016/j.heares.2012.12.014 }}</ref>

| |

| − | * By age 80, more than half of all Americans either have a [[cataract]] or have had [[cataract surgery]].<ref name=NIH2009>{{cite web|title=Facts About Cataract|url=https://www.nei.nih.gov/health/cataract/cataract_facts|access-date=14 August 2016|date=September 2015}}</ref>

| |

| − | * [[Frailty syndrome|Frailty]], a syndrome of decreased strength, physical activity, physical performance and energy, affects 25% of those over 85.<ref name=Fried_2001>{{cite journal | vauthors = Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, Newman AB, Hirsch C, Gottdiener J, Seeman T, Tracy R, Kop WJ, Burke G, McBurnie MA | display-authors = 6 | title = Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype | journal = The Journals of Gerontology. Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences | volume = 56 | issue = 3 | pages = M146-56 | date = March 2001 | pmid = 11253156 | doi = 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146 | citeseerx = 10.1.1.456.139 }}</ref><ref>Percentage derived from Table 2 in Fried et al. 2001</ref>

| |

| − | * [[Atherosclerosis]] is classified as an ageing disease.<ref name="Wang 2012">{{cite journal | vauthors = Wang JC, Bennett M | title = Aging and atherosclerosis: mechanisms, functional consequences, and potential therapeutics for cellular senescence | journal = Circulation Research | volume = 111 | issue = 2 | pages = 245–59 | date = July 2012 | pmid = 22773427 | doi = 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261388 | doi-access = free }}</ref> It leads to cardiovascular disease (for example [[stroke]] and [[Myocardial infarction|heart attack]])<ref name="Wang 2016">{{cite journal | vauthors = Herrington W, Lacey B, Sherliker P, Armitage J, Lewington S | title = Epidemiology of Atherosclerosis and the Potential to Reduce the Global Burden of Atherothrombotic Disease | journal = Circulation Research | volume = 118 | issue = 4 | pages = 535–46 | date = February 2016 | pmid = 26892956 | doi = 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307611 | doi-access = free }}</ref> which globally is the most common cause of death.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death |title=The top 10 causes of death |author=<!--Not stated—> |date=9 December 2020 |publisher=WHO |access-date=11 March 2021}}</ref> Vessel ageing causes vascular remodeling and loss of arterial elasticity and as a result causes the stiffness of the vasculature.<ref name="Wang 2012"/>

| |

| − | * Recent evidence suggests that age-related risk of death plateaus after age 105.<ref>{{cite web |url=https://www.webmd.com/healthy-aging/news/20180628/does-human-life-span-really-have-a-limit#1|title=Does Human Life Span Really Have a Limit?|website=WebMD|date=28 June 2018}}</ref> The maximum human lifespan is suggested to be [[Old age|115 years]].<ref name="NYT-20161005">{{cite news |last=Zimmer |first=Carl |author-link=Carl Zimmer |title=What's the Longest Humans Can Live? 115 Years, New Study Says |url=https://www.nytimes.com/2016/10/06/science/maximum-life-span-study.html |date=5 October 2016 |work=[[The New York Times]] |access-date=6 October 2016 }}</ref><ref name="NAT-20151005">{{cite journal | vauthors = Dong X, Milholland B, Vijg J | title = Evidence for a limit to human lifespan | journal = Nature | volume = 538 | issue = 7624 | pages = 257–259 | date = October 2016 | pmid = 27706136 | doi = 10.1038/nature19793 | s2cid = 3623127 | bibcode = 2016Natur.538..257D }}</ref> The oldest reliably recorded human was [[Jeanne Calment]] who died in 1997 at 122.

| |

| | | | |

| − | [[Dementia]] becomes more common with age.<ref name=Larson2013>{{cite journal | vauthors = Larson EB, Yaffe K, Langa KM | title = New insights into the dementia epidemic | journal = The New England Journal of Medicine | volume = 369 | issue = 24 | pages = 2275–7 | date = December 2013 | pmid = 24283198 | pmc = 4130738 | doi = 10.1056/nejmp1311405 }}</ref> About 3% of people between the ages of 65 and 74, 19% between 75 and 84, and nearly half of those over 85 years of age have dementia.<ref>{{cite book|last1=Umphred|first1=Darcy| name-list-style = vanc |title=Neurological rehabilitation|date=2012|publisher=Elsevier Mosby|location=St. Louis, MO|isbn=978-0-323-07586-2|page=838|edition=6th|url=https://books.google.com/books?id=I9ltC-ZrNOMC&pg=PA838}}</ref> The spectrum ranges from [[mild cognitive impairment]] to the neurodegenerative diseases of [[Alzheimer's disease]], [[cerebrovascular disease]], [[Parkinson's disease]] and [[Lou Gehrig's disease]]. Furthermore, many types of [[Memory and aging|memory decline with ageing]], but not [[semantic memory]] or general knowledge such as vocabulary definitions, which typically increases or remains steady until late adulthood<ref name="Schaie2005">{{cite book|last1=Schaie|first1=K. Warner v|year=2005|doi=10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195156737.001.0001|title=Developmental Influences on Adult Intelligence|isbn=978-0-19-515673-7}}{{page needed|date=November 2013}}</ref> (see [[Aging brain|Ageing brain]]). [[Intelligence]] declines with age, though the rate varies depending on the [[Theory of multiple intelligences|type]] and may in fact remain steady throughout most of the lifespan, dropping suddenly only as people near the end of their lives. Individual variations in rate of cognitive decline may therefore be explained in terms of people having different lengths of life.<ref name=Stuart>{{cite book| vauthors = Stuart-Hamilton I |title=The Psychology of Ageing: An Introduction|publisher=Jessica Kingsley Publishers|location=London|year=2006|isbn=978-1-84310-426-1}}</ref> There are changes to the brain: after 20 years of age there is a 10% reduction each decade in the total length of the brain's [[myelinated]] [[axons]].<ref name="Marner">{{cite journal | vauthors = Marner L, Nyengaard JR, Tang Y, Pakkenberg B | title = Marked loss of myelinated nerve fibers in the human brain with age | journal = The Journal of Comparative Neurology | volume = 462 | issue = 2 | pages = 144–52 | date = July 2003 | pmid = 12794739 | doi = 10.1002/cne.10714 | s2cid = 35293796 }}</ref><ref>{{cite book|chapter-url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK3873/|title=Brain Aging: Models, Methods, and Mechanisms| vauthors = Peters A | veditors = Riddle DR |date=1 January 2007|publisher=CRC Press/Taylor & Francis|pmid=21204349|isbn=978-0-8493-3818-2|chapter=The Effects of Normal Aging on Nerve Fibers and Neuroglia in the Central Nervous System|series=Frontiers in Neuroscience}}</ref>

| + | == Effects == |

| | + | [[File:Senescence.JPG|thumb|300px|Enlarged ears and noses of old humans are sometimes blamed on continual cartilage growth, but the cause is more probably gravity.<ref>Stephen Moss, [https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/shortcuts/2013/jul/17/big-ears-grow-as-we-age Big ears: they really do grow as we age] ''The Guardian'', July 17, 2013. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref>]] |

| | | | |

| − | Age can result in [[visual impairment]], whereby [[non-verbal communication]] is reduced,<ref>{{cite book | vauthors = Worrall L, Hickson LM | date = 2003 | chapter = Theoretical foundations of communication disability in aging | title = Communication disability in aging: from prevention to intervention | pages = 32–33 | veditors = Worrall L, Hickson LM | location = Clifton Park, NY | publisher = Delmar Learning }}</ref> which can lead to isolation and possible depression. Older adults, however, may not suffer depression as much as younger adults, and were paradoxically found to have improved mood despite declining physical health.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Lys R, Belanger E, Phillips SP | title = Improved mood despite worsening physical health in older adults: Findings from the International Mobility in Aging Study (IMIAS) | journal = PLOS ONE | volume = 14 | issue = 4 | pages = e0214988 | date = April 2019 | pmid = 30958861 | pmc = 6453471 | doi = 10.1371/journal.pone.0214988 | bibcode = 2019PLoSO..1414988L }}</ref> [[Macular degeneration]] causes vision loss and increases with age, affecting nearly 12% of those above the age of 80.<ref name="Meh2015">{{cite journal | vauthors = Mehta S | title = Age-Related Macular Degeneration | journal = Primary Care | volume = 42 | issue = 3 | pages = 377–91 | date = September 2015 | pmid = 26319344 | doi = 10.1016/j.pop.2015.05.009 }}</ref> This degeneration is caused by systemic changes in the circulation of waste products and by growth of abnormal vessels around the retina.<ref name="Nussbaum, J. F. 1989">{{cite book | vauthors = Nussbaum JF, Thompson TL, Robinson JD | date = 1989 | chapter = Barriers to conversation | pages = 234–53 | veditors = Nussbaum JF, Thompson TL, Robinson JD | title = Communication and aging | location = New York | publisher = Harper & Row }}</ref>

| + | [[File: Age dynamics of the body mass.png|thumb|400px|Age dynamics of the body mass (1, 2) and mass normalized to height (3, 4) of men (1, 3) and women (2, 4).<ref name="Age dynamics">I. G. Gerasimov and Dmitry Yu Ignatov, [https://www.researchgate.net/publication/226729610_Age_Dynamics_of_Body_Mass_and_Human_Lifespan Age Dynamics of Body Mass and Human Lifespan] ''Journal of Evolutionary Biochemistry and Physiology'' 40(3) (2004):343–349. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref>]] |

| | | | |

| − | Other visual diseases that often appear with age would be cataracts and glaucoma. A cataract occurs when the lens of the eye becomes cloudy making vision blurry and eventually causing blindness if untreated.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Cataracts {{!}} National Eye Institute|url=https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/cataracts|access-date=2021-07-03|website=www.nei.nih.gov}}</ref> They develop over time and are seen most often with those that are older. Cataracts can be treated through surgery. Glaucoma is another common visual disease that appears in older adults. Glaucoma is caused by damage to the optic nerve causing vision loss.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Glaucoma {{!}} National Eye Institute|url=https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/glaucoma|access-date=2021-07-03|website=www.nei.nih.gov}}</ref> Glaucoma usually develops over time but there are variations to glaucoma, and some have sudden onset. There are a few procedures for glaucoma but there is no cure or fix for the damage once it has happened. Prevention is the best measure in the case of glaucoma.<ref>{{Cite web|title=Glaucoma {{!}} National Eye Institute|url=https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/glaucoma|access-date=2021-07-03|website=www.nei.nih.gov}}</ref>

| + | [[File:Alzheimer's disease brain comparison.jpg|thumb|400px|Comparison of a normal aged brain (left) and a brain affected by [[Alzheimer's disease]] (right).]] |

| | | | |

| − | A distinction can be made between "proximal ageing" (age-based effects that come about because of factors in the recent past) and "distal ageing" (age-based differences that can be traced to a cause in a person's early life, such as childhood [[poliomyelitis]]).<ref name=Stuart/>

| + | In humans, aging represents the accumulation of changes in a [[human being]] over time and can encompass [[Human body|physical]], [[psychological]], and social changes. Reaction time, for example, may slow with age, while memories and general knowledge typically increase. Aging also increases the [[risk factor|risk]] of [[disease]]s. |

| | | | |

| | + | A number of characteristic aging symptoms are experienced by a significant proportion of human beings during their lifetimes, including the following: |

| | + | |

| | + | * After peaking in the mid-20s, female [[fertility]] declines.<ref>[https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK293711/ Infertility: Overview] ''Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care'', March 25, 2015. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| | + | * After age 30 the mass of human body is decreased until 70 years and then shows damping oscillations.<ref name="Age dynamics"/> |

| | + | * Muscles have reduced capacity of responding to exercise or injury and loss of muscle mass and strength ([[sarcopenia]]) is common.<ref>James G. Ryall, Jonathan D. Schertzer, and Gordon S. Lynch, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18299960/ Cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying age-related skeletal muscle wasting and weakness] ''Biogerontology'' 9(4) (August 2008): 213–228. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> |

| | + | *Hand strength and mobility are decreased during the aging process. These things include "hand and finger strength and ability to control submaximal pinch force and maintain a steady precision pinch posture, manual speed, and hand sensation."<ref>Vinoth K. Ranganathan, Vlodek Siemionow, Vinod Sahgal, and Guang H. Yue, [https://agsjournals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911240.x Effects of Aging on Hand Function] ''Journal of the American Geriatrics Society'' 49(11) (November 2001):1478–1484. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| | + | * People over 35 years of age are at increasing risk for losing strength in the [[ciliary muscle]] of the [[eye]]s which leads to difficulty focusing on close objects, or [[presbyopia]].<ref>[https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/refractive-errors Refractive Errors] ''National Eye Institute''. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> Most people experience [[presbyopia]] by age 45–50. |

| | + | * Around age 50, [[hair]] turns grey. [[Pattern hair loss]] or [[baldness]] by the age of 50 affects about 50 percent of men and 25 percent of women. |

| | + | * [[Menopause]] typically occurs between 44 and 58 years of age. |

| | + | * In the 60–64 age cohort, the incidence of [[osteoarthritis]] rises. |

| | + | * [[Wrinkle]]s develop mainly due to [[photoaging|photoageing]], particularly affecting sun-exposed areas (face). |

| | + | * Almost half of people older than 75 have [[hearing loss]] (presbycusis) inhibiting spoken communication.<ref>[https://www.nidcd.nih.gov/health/hearing-loss-older-adults Hearing Loss and Older Adults] ''National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders''. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| | + | * By age 80, more than half of all Americans either have a [[cataract]] or have had [[cataract surgery]].<ref>[https://www.nei.nih.gov/learn-about-eye-health/eye-conditions-and-diseases/cataracts Cataracts] ''National Eye Institute''. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| | + | * [[Frailty syndrome|Frailty]], a syndrome of decreased strength, physical activity, physical performance and energy, affects 25 percent of those over 85.<ref>L.P. Fried, C.M. Tangen, J. Walston, A.B. Newman, C. Hirsch, J. Gottdiener, T. Seeman, R. Tracy, W.J. Kop, G. Burke, and M.A. McBurnie, [https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11253156/ Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype] ''The Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences'' 56(3) (March 2001): M146-156. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> |

| | + | * [[Atherosclerosis]] is classified as an aging disease, which leads to cardiovascular disease (for example [[stroke]] and [[Myocardial infarction|heart attack]]), globally the most common causes of death.<ref>[https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death The top 10 causes of death] ''World Health Organization'', December 9, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2022.</ref> |

| | + | *[[Dementia]] becomes more common with age. The spectrum ranges from [[mild cognitive impairment]] to the neurodegenerative diseases of [[Alzheimer's disease]], [[cerebrovascular disease]], [[Parkinson's disease]] and [[Lou Gehrig's disease]]. bout 3 percent of people between the ages of 65 and 74, 19 percent between 75 and 84, and nearly half of those over 85 years of age have dementia.<ref> Rolando T. Lazaro, Sandra G. Reina-Guerra, and Myla Quiben, ''Umphred's Neurological Rehabilitation'' (Mosby, 2019, ISBN 0323611176).</ref> Furthermore, many types of [[Memory and aging|memory decline with aging]], but not [[semantic memory]] or general knowledge such as vocabulary definitions, which typically increases or remains steady until late adulthood.<ref>K. Warner Schaie, ''Developmental Influences on Adult Intelligence'' (Oxford University Press, 2012, ISBN 0195386132). </ref> Individual variations in rate of cognitive decline may be explained in terms of people having different lengths of life.<ref>Ian Stuart-Hamilton, ''The Psychology of Ageing: An Introduction'' (Jessica Kingsley Publishers, 2012, ISBN 184905245X).</ref> |

| | | | |

| | == Prevention and delay == | | == Prevention and delay == |

| − | | + | Human beings who do not have a belief in an [[afterlife]], the continued existence of an eternal [[spirit]] or [[soul]] after the [[death]] of their physical body, have sought ways to prevent aging and death, or at least to delay the process. Such research supports each individual's likelihood of living their full lifespan in good [[health]]. The following are factors which have been found to increase the length and quality of life. |

| | | | |

| | ===Lifestyle=== | | ===Lifestyle=== |

| − | [[Caloric restriction]] substantially affects lifespan in many animals, including the ability to delay or prevent many age-related diseases.<ref name="Guarente2005">{{cite journal | vauthors = Guarente L, Picard F | title = Calorie restriction—the SIR2 connection | journal = Cell | volume = 120 | issue = 4 | pages = 473–82 | date = February 2005 | pmid = 15734680 | doi = 10.1016/j.cell.2005.01.029 | s2cid = 14245512 }}</ref> Typically, this involves caloric intake of 60–70% of what an ''[[ad libitum#Biology|ad libitum]]'' animal would consume, while still maintaining proper nutrient intake.<ref name="Guarente2005"/> In rodents, this has been shown to increase lifespan by up to 50%;<ref name="Agarwal2011">{{cite journal | vauthors = Agarwal B, Baur JA | title = Resveratrol and life extension | journal = Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences | volume = 1215 | issue = 1 | pages = 138–43 | date = January 2011 | pmid = 21261652 | doi = 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05850.x | bibcode = 2011NYASA1215..138A | s2cid = 41701458 | doi-access = free }}</ref> similar effects occur for yeast and ''Drosophila''.<ref name="Guarente2005"/> No lifespan data exist for humans on a calorie-restricted diet,<ref name="Junnila2013"/> but several reports support protection from age-related diseases.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Larson-Meyer DE, Newcomer BR, Heilbronn LK, [[Júlia Volaufová|Volaufova J]], Smith SR, Alfonso AJ, Lefevre M, Rood JC, Williamson DA, Ravussin E | display-authors = 6 | title = Effect of 6-month calorie restriction and exercise on serum and liver lipids and markers of liver function | journal = Obesity | volume = 16 | issue = 6 | pages = 1355–62 | date = June 2008 | pmid = 18421281 | pmc = 2748341 | doi = 10.1038/oby.2008.201 }}</ref><ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Heilbronn LK, de Jonge L, Frisard MI, DeLany JP, Larson-Meyer DE, Rood J, Nguyen T, Martin CK, Volaufova J, Most MM, Greenway FL, Smith SR, Deutsch WA, Williamson DA, Ravussin E | display-authors = 6 | title = Effect of 6-month calorie restriction on biomarkers of longevity, metabolic adaptation, and oxidative stress in overweight individuals: a randomized controlled trial | journal = JAMA | volume = 295 | issue = 13 | pages = 1539–48 | date = April 2006 | pmid = 16595757 | pmc = 2692623 | doi = 10.1001/jama.295.13.1539 }}</ref> Two major ongoing studies on [[Rhesus macaque|rhesus monkeys]] initially revealed disparate results; while one study, by the University of Wisconsin, showed that caloric restriction does extend lifespan,<ref name = "Colman2009">{{cite journal | vauthors = Colman RJ, Anderson RM, Johnson SC, Kastman EK, Kosmatka KJ, Beasley TM, Allison DB, Cruzen C, Simmons HA, Kemnitz JW, Weindruch R | display-authors = 6 | title = Caloric restriction delays disease onset and mortality in rhesus monkeys | journal = Science | volume = 325 | issue = 5937 | pages = 201–4 | date = July 2009 | pmid = 19590001 | pmc = 2812811 | doi = 10.1126/science.1173635 | bibcode = 2009Sci...325..201C }}</ref> the second study, by the National Institute on Aging (NIA), found no effects of caloric restriction on longevity.<ref>{{cite journal | vauthors = Mattison JA, Roth GS, Beasley TM, Tilmont EM, Handy AM, Herbert RL, Longo DL, Allison DB, Young JE, Bryant M, Barnard D, Ward WF, Qi W, Ingram DK, de Cabo R | display-authors = 6 | title = Impact of caloric restriction on health and survival in rhesus monkeys from the NIA study | journal = Nature | volume = 489 | issue = 7415 | pages = 318–21 | date = September 2012 | pmid = 22932268 | pmc = 3832985 | doi = 10.1038/nature11432 | bibcode = 2012Natur.489..318M }}</ref> Both studies nevertheless showed improvement in a number of health parameters. Notwithstanding the similarly low calorie intake, the diet composition differed between the two studies (notably a high [[sucrose]] content in the Wisconsin study), and the monkeys have different origins (India, China), initially suggesting that genetics and dietary composition, not merely a decrease in calories, are factors in longevity.<ref name="Junnila2013"/> However, in a comparative analysis in 2014, the Wisconsin researchers found that the allegedly non-starved NIA control monkeys in fact are moderately underweight when compared with other monkey populations, and argued this was due to the NIA's apportioned feeding protocol in contrast to Wisconsin's truly unrestricted ''ad libitum'' feeding protocol.<ref name=Colman2014>{{cite journal | vauthors = Colman RJ, Beasley TM, Kemnitz JW, Johnson SC, Weindruch R, Anderson RM | title = Caloric restriction reduces age-related and all-cause mortality in rhesus monkeys | journal = Nature Communications | volume = 5 | pages = 3557 | date = April 2014 | pmid = 24691430 | pmc = 3988801 | doi = 10.1038/ncomms4557 | bibcode = 2014NatCo...5.3557C }}</ref> They conclude that moderate calorie restriction rather than extreme calorie restriction is sufficient to produce the observed health and longevity benefits in the studied rhesus monkeys.<ref>"There may be little advantage of moderate CR over modest CR—this would be an extremely important discovery and one that merits further investigation."</ref> | + | A healthy [[diet]] may reduce the effects of aging. For example, the [[Mediterranean diet]] is credited with lowering the risk of heart disease and early death. The major contributors to mortality risk reduction appear to be a higher consumption of vegetables, fish, fruits, nuts, and monounsaturated fatty acids ([[olive]] oil).<ref name>[https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2016/08/160829094040.htm Mediterranean diet associated with lower risk of early death in cardiovascular disease patients] ''European Society of Cardiology'', August 29, 2016. Retrieved May 31, 2022. </ref> |

| − | | |