ADHD

| Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder | |

| |

| Symptoms | Inattention, carelessness, hyperactivity, executive dysfunction, disinhibition, emotional dysregulation, impulsivity, impaired working memory |

|---|---|

| Usual onset | Symptoms should onset in developmental period unless ADHD occurred after traumatic brain injury (TBI). |

| Causes | Genetic (inherited, de novo) and to a lesser extent, environmental factors (exposure to biohazards during pregnancy, traumatic brain injury) |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms after other possible causes have been ruled out |

| Differential diagnosis | Normally active child, bipolar disorder, cognitive disengagement syndrome, conduct disorder, major depressive disorder, autism spectrum disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, learning disorder, intellectual disability, anxiety disorder, borderline personality disorder, fetal alcohol spectrum disorder |

| Treatment | Psychotherapy, lifestyle changes, medication |

| Medication | CNS stimulants (methylphenidate, amphetamine), non-stimulants (atomoxetine, viloxazine), alpha-2a agonists (guanfacine XR, clonidine XR) |

| Frequency | 0.8–1.5% |

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by executive dysfunction occasioning symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity and emotional dysregulation that are excessive and pervasive, impairing in multiple contexts, and otherwise age-inappropriate. Although people with ADHD struggle to sustain attention on tasks that entail delayed rewards or consequences, they are often able to maintain an unusually prolonged and intense level of attention for tasks they do find interesting or rewarding; this is known as hyperfocus.

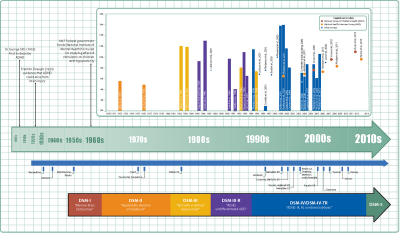

ADHD, its diagnosis, and its treatment have been considered controversial since the 1970s. ADHD was officially known as attention deficit disorder (ADD) from 1980 to 1987; prior to the 1980s, it was known as hyperkinetic reaction of childhood. ADHD is now a well-validated clinical diagnosis in children and adults, and the debate in the scientific community mainly centers on how it is diagnosed and treated. ADHD management recommendations vary and usually involve some combination of medications, counseling, and lifestyle changes.

History

Hyperactivity has long been part of the human condition. Sir Alexander Crichton described "mental restlessness" in his book An Inquiry Into The Nature And Origin Of Mental Derangement written in 1798. He made observations about children showing signs of being inattentive and having the "fidgets."[2]

The first clear description of ADHD is credited to George Still in 1902 during a series of lectures he gave to the Royal College of Physicians of London.[3] He noted that both nature and nurture could be influencing this disorder.

The terminology used to describe the condition has changed over time. Prior to the DSM, terms included minimal brain damage in the 1930s.[4] Other terms include: minimal brain dysfunction in the DSM-I (1952), hyperkinetic reaction of childhood in the DSM-II (1968), and attention-deficit disorder with or without hyperactivity in the DSM-III (1980).[1] In 1987, this was changed to Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the DSM-III-R, and in 1994 the DSM-IV in split the diagnosis into three subtypes: ADHD inattentive type, ADHD hyperactive-impulsive type, and ADHD combined type.[5] These terms were kept in the DSM-5 in 2013[6] and in the DSM-5-TR in 2022.[7]

Signs and symptoms

ADHD is characterized by symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and emotional dysregulation that are excessive and pervasive, impairing in multiple contexts, and otherwise age-inappropriate.[6][7][8] The signs and symptoms can be difficult to define, as it is hard to draw a line at where normal levels of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity end and significant levels requiring interventions begin.[9]

In children, problems paying attention may result in poor school performance. ADHD is associated with other neurodevelopmental and mental disorders as well as some non-psychiatric disorders, which can cause additional impairment, especially in modern society. Although people with ADHD struggle to sustain attention on tasks that entail delayed rewards or consequences, they are often able to maintain an unusually prolonged and intense level of attention for tasks they do find interesting or rewarding; this is known as hyperfocus.

Inattention, hyperactivity (restlessness in adults), disruptive behavior, and impulsivity are common in ADHD. Academic difficulties are frequent as are problems with relationships.[10] Elevated accident-proneness has been found in ADHD patients.[11]

Significantly more males than females are diagnosed with ADHD. It has been suggested that this could be due to gender differences in how ADHD presents. Boys and men tend to display more hyperactive and impulsive behavior while girls and women are more likely to have inattentive symptoms. There are also gender differences in how these symptomatic and behavioral differences are manifested.[12]

Symptoms are expressed differently and more subtly as the individual ages:

Whereas the core symptoms of hyperactivity, impulsivity and inattention, are well characterised in children, these symptoms may have different and more subtle expressions in adult life. [13]

Hyperactivity tends to become less overt with age and turns into inner restlessness, difficulty relaxing or remaining still, talkativeness or constant mental activity in teens and adults with ADHD:

For instance, where children with ADHD may run and climb excessively, or have difficulty in playing or engaging quietly in leisure activities, adults with ADHD are more likely to experience inner restlessness, inability to relax, or over talkativeness. Hyperactivity may also be expressed as excessive fidgeting, the inability to sit still for long in situations when sitting is expected (at the table, in the movie, in church or at symposia), or being on the go all the time. ... For example, physical overactivity in children could be replaced in adulthood by constant mental activity, feelings of restlessness and difficulty engaging in sedentary activities.[13]

Impulsivity in adulthood may appear as thoughtless behavior, impatience, irresponsible spending and sensation-seeking behaviors, while inattention may appear as becoming easily bored, difficulty with organization, remaining on task and making decisions, and sensitivity to stress:

Impulsivity may be expressed as impatience, acting without thinking, spending impulsively, starting new jobs and relationships on impulse, and sensation seeking behaviours. ... Inattention often presents as distractibility, disorganization, being late, being bored, need for variation, difficulty making decisions, lack of overview, and sensitivity to stress.[13]

Although not listed as an official symptom for this condition, emotional dysregulation or mood lability is generally understood to be a common symptom of ADHD.[13]

Diagnosis

ADHD is diagnosed by an assessment of a person's behavioral and mental development, including ruling out the effects of drugs, medications, and other medical or psychiatric problems as explanations for the symptoms. ADHD diagnosis often takes into account feedback from parents and teachers.[14]

In North America and Australia, DSM-5 criteria are used for diagnosis, while European countries usually use the ICD-11. ADHD is alternately classified as neurodevelopmental disorder[15] or a disruptive behavior disorder along with Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), Conduct disorder (CD), and antisocial personality disorder.[16]

Self-rating scales, such as the ADHD rating scale and the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic rating scale, are used in the screening and evaluation of ADHD.[17]

Classification

ADHD is divided into three primary presentations:

- predominantly inattentive (ADHD-PI or ADHD-I)

- predominantly hyperactive-impulsive (ADHD-PH or ADHD-HI)

- combined presentation (ADHD-C).

The table below lists the symptoms for ADHD-I and ADHD-HI from the two major classification systems. Symptoms which can be better explained by another psychiatric or medical condition which an individual has are not considered to be a symptom of ADHD for that person.

| Presentations | DSM-5[6] and DSM-5-TR[7] symptoms | ICD-11[8] symptoms |

|---|---|---|

| Inattention | Six or more of the following symptoms in children, and five or more in adults, excluding situations where these symptoms are better explained by another psychiatric or medical condition:

|

Multiple symptoms of inattention that directly negatively impact occupational, academic or social functioning. Symptoms may not be present when engaged in highly stimulating tasks with frequent rewards. Symptoms are generally from the following clusters:

The individual may also meet the criteria for hyperactivity-impulsivity, but the inattentive symptoms are predominant. |

| Hyperactivity-Impulsivity | Six or more of the following symptoms in children, and five or more in adults, excluding situations where these symptoms are better explained by another psychiatric or medical condition:

|

Multiple symptoms of hyperactivity/impulsivity that directly negatively impact occupational, academic or social functioning. Typically, these tend to be most apparent in environments with structure or which require self-control. Symptoms are generally from the following clusters:

The individual may also meet the criteria for inattention, but the hyperactive-impulsive symptoms are predominant. |

| Combined | Meet the criteria for both inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive ADHD. | Criteria are met for both inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive ADHD, with neither clearly predominating. |

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual

As with many other psychiatric disorders, a formal diagnosis should be made by a qualified professional based on a set number of criteria. In the United States, these criteria are defined by the American Psychiatric Association in the DSM. Based on the DSM-5 criteria published in 2013 and the DSM-5-TR criteria published in 2022, there are three presentations of ADHD:

- ADHD, predominantly inattentive type, presents with symptoms including being easily distracted, forgetful, daydreaming, disorganization, poor concentration, and difficulty completing tasks.

- ADHD, predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type, presents with excessive fidgeting and restlessness, hyperactivity, and difficulty waiting and remaining seated.

- ADHD, combined type, a combination of the first two presentations.

Symptoms must be present for six months or more to a degree that is much greater than others of the same age. This requires at least six symptoms of either inattention or hyperactivity/impulsivity for those under 17 and at least five symptoms for those 17 years or older. The symptoms must be present in at least two settings (such as social, school, work, or home), and must directly interfere with or reduce quality of functioning.[6] Additionally, several symptoms must have been present before age twelve.[7]

The DSM-5 and the DSM-5-TR also provide two diagnoses for individuals who have symptoms of ADHD but do not entirely meet the requirements. Other Specified ADHD allows the clinician to describe why the individual does not meet the criteria, whereas Unspecified ADHD is used where the clinician chooses not to describe the reason.

International Classification of Diseases

In the eleventh revision of the World Health Organization's ICD-11, the disorder is classified as Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (code 6A05). The defined subtypes are similar to those of the DSM-5: predominantly inattentive presentation (6A05.0); predominantly hyperactive-impulsive presentation(6A05.1); combined presentation (6A05.2). The ICD-11 also includes the two residual categories for individuals who do not entirely match any of the defined subtypes: other specified presentation (6A05.Y) where the clinician includes detail on the individual's presentation; and presentation unspecified (6A05.Z) where the clinician does not provide detail.[8]

Adults

Adults with ADHD are diagnosed under the same criteria as children, including that their signs must have been present by the age of six to twelve. The individual is the best source for information in diagnosis, however others may provide useful information about the individual's symptoms currently and in childhood; a family history of ADHD also adds weight to a diagnosis.

While the core symptoms of ADHD are similar in children and adults, they often present differently: Excessive physical activity seen in children may present as feelings of restlessness and constant mental activity in adults. Adults with ADHD may start relationships impulsively, display sensation-seeking behaviour, and be short-tempered. Addictive behavior such as substance abuse and gambling are common.[13]

Differential diagnosis

The DSM provides potential differential diagnoses – potential alternate explanations for specific symptoms. Assessment and investigation of clinical history determines which is the most appropriate diagnosis. The DSM-5 suggests ODD, intermittent explosive disorder, and other neurodevelopmental disorders (such as stereotypic movement disorder and Tourette's disorder), in addition to specific learning disorder, intellectual developmental disorder, ASD, reactive attachment disorder, anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, bipolar disorder, disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, substance use disorder, personality disorders, psychotic disorders, medication-induced symptoms, and neurocognitive disorders. Many but not all of these are also common comorbidities of ADHD.[6] The DSM-5-TR also suggests post-traumatic stress disorder.[7]

Primary sleep disorders may affect attention and behavior and the symptoms of ADHD may affect sleep. It is thus recommended that children with ADHD be regularly assessed for sleep problems. Sleepiness in children may result in symptoms ranging from the classic ones of yawning and rubbing the eyes, to hyperactivity and inattentiveness. Obstructive sleep apnea can also cause ADHD-type symptoms.

Comorbidities

Psychiatric

In children, ADHD occurs with other disorders about two-thirds of the time.[18]

Other neurodevelopmental conditions are common comorbidities. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD), co-occurring at a rate of 21% in those with ADHD, affects social skills, ability to communicate, behaviour, and interests.[19][20] Both ADHD and ASD can be diagnosed in the same person.[7] Learning disabilities have been found to occur in about 20–30% of children with ADHD. Learning disabilities can include developmental speech and language disorders, and academic skills disorders.[21] ADHD, however, is not considered a learning disability, but it very frequently causes academic difficulties.[21] Intellectual disabilities[7] and Tourette's syndrome[20] are also common.

ADHD is often comorbid with disruptive, impulse control, and conduct disorders. Oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) occurs in about 25% of children with an inattentive presentation and 50% of those with a combined presentation. It is characterised by angry or irritable mood, argumentative or defiant behaviour and vindictiveness which are age-inappropriate. Conduct disorder (CD) occurs in about 25% of adolescents with ADHD.[7] It is characterised by aggression, destruction of property, deceitfulness, theft and violations of rules.[22] Adolescents with ADHD who also have CD are more likely to develop antisocial personality disorder in adulthood.[23] Brain imaging supports that CD and ADHD are separate conditions, wherein conduct disorder was shown to reduce the size of one's temporal lobe and limbic system, and increase the size of one's orbitofrontal cortex, whereas ADHD was shown to reduce connections in the cerebellum and prefrontal cortex more broadly. Conduct disorder involves more impairment in motivation control than ADHD.[24] Intermittent explosive disorder is characterised by sudden and disproportionate outbursts of anger and co-occurs in individuals with ADHD more frequently than in the general population.

Anxiety and mood disorders are frequent comorbidities. Anxiety disorders have been found to occur more commonly in the ADHD population, as have mood disorders (especially bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder). Boys diagnosed with the combined ADHD subtype are more likely to have a mood disorder.[25] Adults and children with ADHD sometimes also have bipolar disorder, which requires careful assessment to accurately diagnose and treat both conditions.[26][27]

Sleep disorders and ADHD commonly co-exist. They can also occur as a side effect of medications used to treat ADHD. In children with ADHD, insomnia is the most common sleep disorder with behavioural therapy being the preferred treatment.[28][29] Problems with sleep initiation are common among individuals with ADHD but often they will be deep sleepers and have significant difficulty getting up in the morning.[30] Melatonin is sometimes used in children who have sleep onset insomnia.[31] Specifically, the sleep disorder restless legs syndrome has been found to be more common in those with ADHD and is often due to iron deficiency anemia.[32][33] However, restless legs can simply be a part of ADHD and requires careful assessment to differentiate between the two disorders.[34] Delayed sleep phase disorder is also a common comorbidity of those with ADHD.[35]

There are other psychiatric conditions which are often co-morbid with ADHD, such as substance use disorders.[36] Individuals with ADHD are at increased risk of substance abuse. This is most commonly seen with alcohol or cannabis.[13] The reason for this may be an altered reward pathway in the brains of ADHD individuals, self-treatment and increased psychosocial risk factors. This makes the evaluation and treatment of ADHD more difficult, with serious substance misuse problems usually treated first due to their greater risks.[37] Other psychiatric conditions include reactive attachment disorder,[38] characterised by a severe inability to appropriately relate socially, and sluggish cognitive tempo, a cluster of symptoms that potentially comprises another attention disorder and may occur in 30–50% of ADHD cases, regardless of the subtype.[39] Individuals with ADHD are three times more likely to develop and be diagnosed with an eating disorder compared to those without ADHD; conversely, individuals with eating disorders are two times more likely to have ADHD than those without eating disorders.[40]

Trauma

ADHD, trauma, and Adverse Childhood Experiences are also comorbid,[41][42] which could in part be potentially explained by the similarity in presentation between different diagnoses. The symptoms of ADHD and PTSD can have significant behavioural overlap—in particular, motor restlessness, difficulty concentrating, distractibility, irritability/anger, emotional constriction or dysregulation, poor impulse control, and forgetfulness are common in both.[43][44] This could result in trauma-related disorders or ADHD being mis-identified as the other.[45] Additionally, traumatic events in childhood are a risk factor for ADHD[46][47] - it can lead to structural brain changes and the development of ADHD behaviours.[45] Finally, the behavioural consequences of ADHD symptoms cause a higher chance of the individual experiencing trauma (and therefore ADHD leads to a concrete diagnosis of a trauma-related disorder).[48]Template:Primary source inline

Non-psychiatric

Some non-psychiatric conditions are also comorbidities of ADHD. This includes epilepsy,[20] a neurological condition characterised by recurrent seizures.[49][50] There are well established associations between ADHD and obesity, asthma and sleep disorders,[51] and an association with celiac disease.[52] Children with ADHD have a higher risk for migraine headaches,[53] but have no increased risk of tension-type headaches. In addition, children with ADHD may also experience headaches as a result of medication.[54][55]

A 2021 review reported that several neurometabolic disorders caused by inborn errors of metabolism converge on common neurochemical mechanisms that interfere with biological mechanisms also considered central in ADHD pathophysiology and treatment. This highlights the importance of close collaboration between health services to avoid clinical overshadowing.[56]

Suicide risk

Systematic reviews conducted in 2017 and 2020 found strong evidence that ADHD is associated with increased suicide risk across all age groups, as well as growing evidence that an ADHD diagnosis in childhood or adolescence represents a significant future suicidal risk factor.[57][58] Potential causes include ADHD's association with functional impairment, negative social, educational and occupational outcomes, and financial distress.[59][60] A 2019 meta-analysis indicated a significant association between ADHD and suicidal spectrum behaviours (suicidal attempts, ideations, plans, and completed suicides); across the studies examined, the prevalence of suicide attempts in individuals with ADHD was 18.9%, compared to 9.3% in individuals without ADHD, and the findings were substantially replicated among studies which adjusted for other variables. However, the relationship between ADHD and suicidal spectrum behaviours remains unclear due to mixed findings across individual studies and the complicating impact of comorbid psychiatric disorders.[59] There is no clear data on whether there is a direct relationship between ADHD and suicidality, or whether ADHD increases suicide risk through comorbidities.[58]

Causes

The precise causes of ADHD are unknown in the majority of cases.[61][62] For most people with ADHD, many genetic and environmental risk factors accumulate to cause the disorder. The environmental risks for ADHD most often exert their influence in the early prenatal period. In some cases a single event might cause ADHD such as traumatic brain injury, exposure to biohazards during pregnancy, a major genetic mutation or extreme nutritional deprivation early in life. Later in life, there is no biologically distinct adult onset ADHD except for when ADHD occurs after traumatic brain injury.[63]

Genetic factors play an important role; ADHD tends to run in families and has a heritability rate of 74%.[64] Toxins and infections during pregnancy as well as brain damage may be environmental risks.

ADHD is generally claimed to be the result of neurological dysfunction in processes associated with the production or use of dopamine and norepinephrine in various brain structures, but there are no confirmed causes.[65][66] It may involve interactions between genetics and the environment.[65][66][67]

Genetics

In November 1999, Biological Psychiatry published a literature review by psychiatrists Joseph Biederman and Thomas Spencer on the pathophysiology of ADHD that found the average heritability estimate of ADHD from twin studies to be 0.8,[68] while a subsequent family, twin, and adoption studies literature review published in Molecular Psychiatry in April 2019 by psychologists Stephen Faraone and Henrik Larsson that found an average heritability estimate of 0.74.[69] Additionally, evolutionary psychiatrist Randolph M. Nesse has argued that the 5:1 male-to-female sex ratio in the epidemiology of ADHD suggests that ADHD may be the end of a continuum where males are overrepresented at the tails, citing clinical psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen's suggestion for the sex ratio in the epidemiology of autism as an analogue.[70][71][72]

ADHD has a high heritability of 74%, meaning that 74% of the presence of ADHD in the population is due to genetic factors. There are multiple gene variants which each slightly increase the likelihood of a person having ADHD; it is polygenic and arises through the combination of many gene variants which each have a small effect.[73][74] The siblings of children with ADHD are three to four times more likely to develop the disorder than siblings of children without the disorder.[75]

Arousal is related to dopaminergic functioning, and ADHD presents with low dopaminergic functioning.[76] Typically, a number of genes are involved, many of which directly affect dopamine neurotransmission.[77] Those involved with dopamine include DAT, DRD4, DRD5, TAAR1, MAOA, COMT, and DBH.[77][78][79] Other genes associated with ADHD include SERT, HTR1B, SNAP25, GRIN2A, ADRA2A, TPH2, and BDNF.[80] A common variant of a gene called latrophilin 3 is estimated to be responsible for about 9% of cases and when this variant is present, people are particularly responsive to stimulant medication.[81] The 7 repeat variant of dopamine receptor D4 (DRD4–7R) causes increased inhibitory effects induced by dopamine and is associated with ADHD. The DRD4 receptor is a G protein-coupled receptor that inhibits adenylyl cyclase. The DRD4–7R mutation results in a wide range of behavioural phenotypes, including ADHD symptoms reflecting split attention.[82] The DRD4 gene is both linked to novelty seeking and ADHD. The genes GFOD1 and CDH13 show strong genetic associations with ADHD. CHD13's association with ASD, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression make it an interesting candidate causative gene.[83] Another candidate causative gene that has been identified is ADGRL3. In zebrafish, knockout of this gene causes a loss of dopaminergic function in the ventral diencephalon and the fish display a hyperactive/impulsive phenotype.[83]

For genetic variation to be used as a tool for diagnosis, more validating studies need to be performed. However, smaller studies have shown that genetic polymorphisms in genes related to catecholaminergic neurotransmission or the SNARE complex of the synapse can reliably predict a person's response to stimulant medication.[83] Rare genetic variants show more relevant clinical significance as their penetrance (the chance of developing the disorder) tends to be much higher.[84] However their usefulness as tools for diagnosis is limited as no single gene predicts ADHD. ASD shows genetic overlap with ADHD at both common and rare levels of genetic variation.[84]

Environment

In addition to genetics, some environmental factors might play a role in causing ADHD.[85][86] Alcohol intake during pregnancy can cause fetal alcohol spectrum disorders which can include ADHD or symptoms like it.[87] Children exposed to certain toxic substances, such as lead or polychlorinated biphenyls, may develop problems which resemble ADHD.[61][88] Exposure to the organophosphate insecticides chlorpyrifos and dialkyl phosphate is associated with an increased risk; however, the evidence is not conclusive.[89] Exposure to tobacco smoke during pregnancy can cause problems with central nervous system development and can increase the risk of ADHD.[61][90] Nicotine exposure during pregnancy may be an environmental risk.[91]

Extreme premature birth, very low birth weight, and extreme neglect, abuse, or social deprivation also increase the risk[92][61][93] as do certain infections during pregnancy, at birth, and in early childhood. These infections include, among others, various viruses (measles, varicella zoster encephalitis, rubella, enterovirus 71).[94] At least 30% of children with a traumatic brain injury later develop ADHD[95] and about 5% of cases are due to brain damage.[96]

Some studies suggest that in a small number of children, artificial food dyes or preservatives may be associated with an increased prevalence of ADHD or ADHD-like symptoms,[61][97] but the evidence is weak and may only apply to children with food sensitivities.[85][97][98] The European Union has put in place regulatory measures based on these concerns.[99] In a minority of children, intolerances or allergies to certain foods may worsen ADHD symptoms.[100]

Individuals with hypokalemic sensory overstimulation are sometimes diagnosed as having attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), raising the possibility that a subtype of ADHD has a cause that can be understood mechanistically and treated in a novel way. The sensory overload is treatable with oral potassium gluconate.

Research does not support popular beliefs that ADHD is caused by eating too much refined sugar, watching too much television, bad parenting, poverty or family chaos; however, they might worsen ADHD symptoms in certain people.[10]

In September 2014, Developmental Psychology published a meta-analysis of 45 studies investigating the relationship between media use and ADHD-related behaviors in children and adolescents and found a small but significant relationship between media use and ADHD-related behaviors.[101] In October 2018, PNAS USA published a systematic review of four decades of research on the relationship between children and adolescents' screen media use and ADHD-related behaviors and concluded that a statistically small relationship between children's media use and ADHD-related behaviors exists.[102] In July 2018, the Journal of the American Medical Association published a two-month longitudinal cohort survey of 3,051 U.S. teenagers ages 15 and 16 (recruited at 10 different Los Angeles County, California secondary schools by convenience sampling) self-reporting engagement in 14 different modern digital media activities at high-frequency. 2,587 subjects had no significant symptoms of ADHD at baseline with a mean number of 3.62 modern digital media activities used at high-frequency and each additional activity used frequently at baseline positively correlating with a significantly higher probability of ADHD symptoms at follow-ups. 495 subjects who reported no high-frequency digital media activities at baseline had a 4.6% mean rate of having ADHD symptoms at follow-ups, as compared with 114 subjects who reported 7 high-frequency activities who had a 9.5% mean rate at follow-ups and 51 subjects with 14 high-frequency activities who had a 10.5% mean rate at follow-ups (indicating a statistically significant but modest association between higher frequency of digital media use and subsequent symptoms of ADHD).[103][104][105]

In April 2019, PLOS One published the results of a longitudinal birth cohort study of screen time use reported by parents of 2,322 children in Canada at ages 3 and 5 and found that compared to children with less than 30 minutes per day of screen time, children with more than 2 hours of screen time per day had a 7.7-fold increased risk of meeting criteria for ADHD.[106] In January 2020, the Italian Journal of Pediatrics published a cross-sectional study of 1,897 children from ages 3 through 6 attending 42 kindergartens in Wuxi, China that also found that children exposed to more than 1 hour of screen-time per day were at increased risk for the development of ADHD and noted its similarity to a finding relating screen time and the development of autism spectrum disorder (ASD).[107] In November 2020, Infant Behavior and Development published a study of 120 3-year-old children with or without family histories of ASD or ADHD (20 with ASD, 14 with ADHD, and 86 for comparison) examining the relationship between screen time, behavioral outcomes, and expressive/receptive language development that found that higher screen time was associated with lower expressive/receptive language scores across comparison groups and that screen time was associated with behavioral phenotype, not family history of ASD or ADHD.[108]

In 2015, Preventive Medicine Reports published a multivariate linear and logistic regression study of 7,024 subjects aged 6–17 in the Maternal and Child Health Bureau's 2007 National Survey of Children's Health examining the association between bedroom televisions and screen time in children and adolescents diagnosed with ADHD that found that 59 percent of subjects had a bedroom television, subjects with bedroom televisions averaged 159.1 minutes of screen time per weekday versus 115.2 minutes per weekday for those without, and after adjusting for child and family characteristics, a bedroom television was associated with 25.1 minutes more of screen time per weekday and a 32.1 percent higher probability of average weekday screen time exceeding 2 hours.[109] In July 2021, Sleep Medicine published a correlational study of 374 French children with a mean age of 10.8±2.8 years where parents completed the Sleep Disturbance Scale for Children (SDSC), the ADHD Rating Scale, and a questionnaire about the subjects screen time habits during the morning, afternoon, and evening that found that subjects with bedroom televisions had greater sleep disturbance and ADHD symptoms, that evening screen time was associated with higher SDSC and ADHD scores, and that structural equation modeling demonstrated that evening screen time was directly associated with greater sleep disturbance which in turn was directly associated with greater ADHD symptoms.[110]

The youngest children in a class have been found to be more likely to be diagnosed as having ADHD, possibly due to them being developmentally behind their older classmates.[111][112] One study showed that the youngest children in fifth and eight grade was nearly twice as likely to use stimulant medication than their older peers.[113]

In some cases, an inappropriate diagnosis of ADHD may reflect a dysfunctional family or a poor educational system, rather than any true presence of ADHD in the individual.[114]Template:Better source needed In other cases, it may be explained by increasing academic expectations, with a diagnosis being a method for parents in some countries to get extra financial and educational support for their child.[96] Behaviours typical of ADHD occur more commonly in children who have experienced violence and emotional abuse.[115]

Pathophysiology

ADHD symptoms arise from executive dysfunction,[30][116][117] ADHD symptoms arise from executive dysfunction, and emotional dysregulation is often considered a core symptom. In children, problems paying attention may result in poor school performance. ADHD is associated with other neurodevelopmental and mental disorders as well as some non-psychiatric disorders, which can cause additional impairment, especially in modern society.

Once neuroimaging studies were possible, studies conducted in the 1990s provided support for the pre-existing theory that neurological differences - particularly in the frontal lobes - were involved in ADHD. During this same period, a genetic component was identified and ADHD was acknowledged to be a persistent, long-term disorder which lasted from childhood into adulthood.[118][119]

Current models of ADHD suggest that it is associated with functional impairments in some of the brain's neurotransmitter systems, particularly those involving dopamine and norepinephrine.[120] The dopamine and norepinephrine pathways that originate in the ventral tegmental area and locus coeruleus project to diverse regions of the brain and govern a variety of cognitive processes.[121][116] The dopamine pathways and norepinephrine pathways which project to the prefrontal cortex and striatum are directly responsible for modulating executive function (cognitive control of behaviour), motivation, reward perception, and motor function;[120][116] these pathways are known to play a central role in the pathophysiology of ADHD.[121][116][122][123] Larger models of ADHD with additional pathways have been proposed.[122][123]

Brain structure

In children with ADHD, there is a general reduction of volume in certain brain structures, with a proportionally greater decrease in the volume in the left-sided prefrontal cortex.[120][124] The posterior parietal cortex also shows thinning in individuals with ADHD compared to controls. Other brain structures in the prefrontal-striatal-cerebellar and prefrontal-striatal-thalamic circuits have also been found to differ between people with and without ADHD.[120][122][123]

The subcortical volumes of the accumbens, amygdala, caudate, hippocampus, and putamen appears smaller in individuals with ADHD compared with controls.[125] Structural MRI studies have also revealed differences in white matter, with marked differences in inter-hemispheric asymmetry between ADHD and typically developing youths.[126]

Function MRI (fMRI) studies have revealed a number of differences between ADHD and control brains. Mirroring what is known from structural findings, fMRI studies have showed evidence for a higher connectivity between subcortical and cortical regions, such as between the caudate and prefrontal cortex. The degree of hyperconnectivity between these regions correlated with the severity of inattention or hyperactivity [127] Hemispheric lateralization processes have also been postulated as being implicated in ADHD, but empiric results showed contrasting evidence on the topic.[128][129]

Neurotransmitter pathways

Previously, it had been suggested that the elevated number of dopamine transporters in people with ADHD was part of the pathophysiology, but it appears the elevated numbers may be due to adaptation following exposure to stimulant medication.[130] Current models involve the mesocorticolimbic dopamine pathway and the locus coeruleus-noradrenergic system.[121][120][116] ADHD psychostimulants possess treatment efficacy because they increase neurotransmitter activity in these systems.[120][116][131] There may additionally be abnormalities in serotonergic, glutamatergic, or cholinergic pathways.[131][132][133]

Executive function and motivation

The symptoms of ADHD arise from a deficiency in certain executive functions (e.g., attentional control, inhibitory control, and working memory).[120] Executive functions are a set of cognitive processes that are required to successfully select and monitor behaviours that facilitate the attainment of one's chosen goals.[116][117] The executive function impairments that occur in ADHD individuals result in problems with staying organised, time keeping, excessive procrastination, maintaining concentration, paying attention, ignoring distractions, regulating emotions, and remembering details.[30][120][116] People with ADHD appear to have unimpaired long-term memory, and deficits in long-term recall appear to be attributed to impairments in working memory.[134] Due to the rates of brain maturation and the increasing demands for executive control as a person gets older, ADHD impairments may not fully manifest themselves until adolescence or even early adulthood.[30] Conversely, brain maturation trajectories, potentially exhibiting diverging longitudinal trends in ADHD, may support a later improvement in executive functions after reaching adulthood.[128]

ADHD has also been associated with motivational deficits in children. Children with ADHD often find it difficult to focus on long-term over short-term rewards, and exhibit impulsive behaviour for short-term rewards.[135]

Paradoxical reaction to neuroactive substances

Another sign of the structurally altered signal processing in the central nervous system in this group of people is the conspicuously common Paradoxical reaction. These are unexpected reactions in the opposite direction to the normal effect, or otherwise significant different reactions. These are reactions to neuroactive substances such as local anesthetic at the dentist, sedative, caffeine, antihistamine, weak neuroleptics, and central and peripheral painkillers.

Management

ADHD management recommendations vary and usually involve some combination of medications, counseling, and lifestyle changes.[136] The British guideline emphasises environmental modifications and education about ADHD for individuals and carers as the first response. If symptoms persist, parent-training, medication, or psychotherapy (especially cognitive behavioural therapy) can be recommended based on age.[137] Canadian and American guidelines recommend medications and behavioural therapy together, except in preschool-aged children for whom the first-line treatment is behavioural therapy alone.[138][139][140]

While treatment may improve long-term outcomes, it does not get rid of negative outcomes entirely.[141]

Behavioural therapies

There is good evidence for the use of behavioural therapies in ADHD. They are the recommended first-line treatment in those who have mild symptoms or who are preschool-aged.[142][143] Psychological therapies used include: psychoeducational input, behavior therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy,[144] interpersonal psychotherapy, family therapy, school-based interventions, social skills training, behavioural peer intervention, organization training,[145] and parent management training.[115] Neurofeedback has greater treatment effects than non-active controls for up to 6 months and possibly a year following treatment, and may have treatment effects comparable to active controls (controls proven to have a clinical effect) over that time period.[146] Despite efficacy in research, there is insufficient regulation of neurofeedback practice, leading to ineffective applications and false claims regarding innovations.[147] Parent training may improve a number of behavioural problems including oppositional and non-compliant behaviours.[148]

There is little high-quality research on the effectiveness of family therapy for ADHD—but the existing evidence shows that it is similar to community care, and better than placebo.[149] ADHD-specific support groups can provide information and may help families cope with ADHD.[150]

Social skills training, behavioural modification, and medication may have some limited beneficial effects in peer relationships. Stable, high-quality friendships with non-deviant peers protect against later psychological problems.[151]

Medication

The use of stimulants to treat ADHD was first described in 1937.[152] Charles Bradley gave the children with behavioral disorders Benzedrine and found it improved academic performance and behavior.[153][154]

Stimulants

Methylphenidate and amphetamine or its derivatives are often first-line treatments for ADHD.[155][156] About 70 per cent respond to the first stimulant tried and as few as 10 per cent respond to neither amphetamines nor methylphenidate.[157] Stimulants may also reduce the risk of unintentional injuries in children with ADHD.[158] Magnetic resonance imaging studies suggest that long-term treatment with amphetamine or methylphenidate decreases abnormalities in brain structure and function found in subjects with ADHD.[159][160][161] A 2018 review found the greatest short-term benefit with methylphenidate in children, and amphetamines in adults.[162] Studies and meta-analyses show that amphetamine is slightly-to-modestly more effective than methylphenidate at reducing symptoms,[163][164] and they are more effective pharmacotherapy for ADHD than α2-agonists[165] but methylphenidate has comparable efficacy to non-stimulants such as atomoxetine.

Non-stimulants

Two non-stimulant medications, atomoxetine and viloxazine, are approved by the FDA and in other countries for the treatment of ADHD. They produce comparable efficacy and tolerability to methylphenidate, but all three tend to be modestly more tolerable and less effective than amphetamines.

Alpha-2a agonists

Two alpha-2a agonists, extended-release formulations of guanfacine and clonidine, are approved by the FDA and in other countries for the treatment of ADHD (effective in children and adolescents but effectiveness has still not been shown for adults).[166][167] They appear to be modestly less effective than the stimulants (amphetamine and methylphenidate) and non-stimulants (atomoxetine and viloxazine) at reducing symptoms,[168][169] but can be useful alternatives or used in conjunction with a stimulant.[157]

Exercise

Regular physical exercise, particularly aerobic exercise, is an effective add-on treatment for ADHD in children and adults, particularly when combined with stimulant medication (although the best intensity and type of aerobic exercise for improving symptoms are not currently known).[170] The long-term effects of regular aerobic exercise in ADHD individuals include better behaviour and motor abilities, improved executive functions (including attention, inhibitory control, and planning, among other cognitive domains), faster information processing speed, and better memory.[171] Parent-teacher ratings of behavioural and socio-emotional outcomes in response to regular aerobic exercise include: better overall function, reduced ADHD symptoms, better self-esteem, reduced levels of anxiety and depression, fewer somatic complaints, better academic and classroom behaviour, and improved social behaviour. Exercising while on stimulant medication augments the effect of stimulant medication on executive function.[172] It is believed that these short-term effects of exercise are mediated by an increased abundance of synaptic dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain.[172]

Prognosis

ADHD persists into adulthood in about 30–50% of cases.[173] Those affected are likely to develop coping mechanisms as they mature, thus compensating to some extent for their previous symptoms.[174] Children with ADHD have a higher risk of unintentional injuries.[158] Effects of medication on functional impairment and quality of life (e.g. reduced risk of accidents) have been found across multiple domains.[175] Rates of smoking among those with ADHD are higher than in the general population at about 40%.[176]

Controversy

ADHD, its diagnosis, and its treatment have been controversial since the 1970s.[177][178] The controversies involve clinicians, teachers, policymakers, parents, and the media. ADHD was officially known as attention deficit disorder (ADD) from 1980 to 1987; prior to the 1980s, it was known as hyperkinetic reaction of childhood.

Positions range from the view that ADHD is within the normal range of behavior[37][179] to the hypothesis that ADHD is a genetic condition.[180] Other areas of controversy include the use of stimulant medications in children,[177] the method of diagnosis, and the possibility of overdiagnosis.[181] In 2009, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, while acknowledging the controversy, states that the current treatments and methods of diagnosis are based on the dominant view of the academic literature.[182] In 2014, Keith Conners, one of the early advocates for recognition of the disorder, spoke out against overdiagnosis in a New York Times article.[183] In contrast, a 2014 peer-reviewed medical literature review indicated that ADHD is underdiagnosed in adults.[184]

With widely differing rates of diagnosis across countries, states within countries, races, and ethnicities, some suspect factors other than the presence of the symptoms of ADHD are playing a role in diagnosis, such as cultural norms.[185][186] Some sociologists consider ADHD to be an example of the medicalization of deviant behaviour, that is, the turning of the previously non-medical issue of school performance into a medical one.[187] Most healthcare providers accept ADHD as a genuine disorder, at least in the small number of people with severe symptoms.

ADHD is now a well-validated clinical diagnosis in children and adults, and the debate in the scientific community mainly centers on how it is diagnosed and treated.[188][189]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 ADHD Throughout the Years Center For Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ↑ Sir Alexander Crichton, An Inquiry Into The Nature And Origin Of Mental Derangement (Legare Street Press, 2022 (original 1798), ISBN 978-1017488913).

- ↑ George Still, The Goulstonian Lectures on some Abnormal Psychical Conditions in Children The Lancet 159(4102) (April 12, 1902):1008-1013. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ↑ Margaret Weiss, Lily Trokenberg Hechtman, and Gabrielle Weiss, ADHD in Adulthood: A Guide to Current Theory, Diagnosis, and Treatment (Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0801868221).

- ↑ J. Gordon Millichap, Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook (Springer, 2009, ISBN 978-1441913968).

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition: DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013, ISBN 978-0890425541).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition Text Revision: DSM-5-TR (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2022, ISBN 0890425760).

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 6A05 Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ICD-11. Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ↑ J. Russell Ramsay and Anthony L. Rostain, Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy for Adult ADHD: An Integrative Psychosocial and Medical Approach (Routledge, 2007, ISBN 978-0415955010).

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 CDC (6 January 2016). Facts About ADHD. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ↑ Nathalie Brunkhorst-Kanaan, Berit Libutzki, Andreas Reif, Henrik Larsson, Rhiannon V. McNeill, and Sarah Kittel-Schneider, ADHD and accidents over the life span – A systematic review Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews (125) (2021):582–591. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ↑ Female vs Male ADHD The ADHD Centre (December 21, 2022). Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 13.5 European consensus statement on diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD: The European Network Adult ADHD BMC Psychiatry 10(67) (2010). Retrieved January 20, 2024.

- ↑ Mina K. Dulcan, Rachel R. Ballard, Poonam Jha, and Julie M. Sadhu, Concise Guide to Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2017, ISBN 978-1615370788).

- ↑ Caroline S. Clauss-Ehlers, Encyclopedia of Cross-Cultural School Psychology (Springer, 2010, ISBN 978-0387717982).

- ↑ Jerry M. Wiener and Mina K. Dulcan (eds.), Textbook Of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (American Psychiatric Publishing, 2003, ISBN 978-1585620579).

- ↑ Eric A. Youngstrom, Mitchell J. Prinstein, Eric J. Mash, and Russell A. Barkley (eds.), Assessment of Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence (The Guilford Press, 2020, ISBN 978-1462543632).

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedWalitza_2012 - ↑ (May 2020) Guidance for identification and treatment of individuals with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism spectrum disorder based upon expert consensus. BMC Medicine 18 (1).

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 ADHD Symptoms (20 October 2017).

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 ADHD and Learning Disabilities: How can you help your child cope with ADHD and subsequent Learning Difficulties? There is a way.. Remedy Health Media, LLC..

- ↑ Evaluation and diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. Uptodate. Wolters Kluwer Health (5 December 2007).

- ↑ (2009). Continuity of aggressive antisocial behavior from childhood to adulthood: The question of phenotype definition. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 32 (4): 224–234.

- ↑ (June 2011) 'Cool' inferior frontostriatal dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder versus 'hot' ventromedial orbitofrontal-limbic dysfunction in conduct disorder: a review. Biological Psychiatry 69 (12): e69–e87.

- ↑ (September 2010) Understanding attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder from childhood to adulthood. Postgraduate Medicine 122 (5): 97–109.

- ↑ (June 2011) [Bipolar disorder and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults: differential diagnosis or comorbidity]. Revue Médicale Suisse 7 (297): 1219–1222.

- ↑ (July 2011) The intersection of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance abuse. Current Opinion in Psychiatry 24 (4): 280–285.

- ↑ (June 2011) A framework for the assessment and treatment of sleep problems in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatric Clinics of North America 58 (3): 667–683.

- ↑ (May 2010) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and sleep disorders in children. The Medical Clinics of North America 94 (3): 615–632.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 30.3 (October 2008) ADD/ADHD and Impaired Executive Function in Clinical Practice. Current Psychiatry Reports 10 (5): 407–411.

- ↑ (January 2010) Melatonin treatment for insomnia in pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The Annals of Pharmacotherapy 44 (1): 185–191.

- ↑ (March 2011) [Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and restless legs syndrome in children]. Revista de Neurología 52 (Suppl 1): S85–S95.

- ↑ (August 2010) Advances in pediatric restless legs syndrome: Iron, genetics, diagnosis and treatment. Sleep Medicine 11 (7): 643–651.

- ↑ (2008). [Restless-legs syndrome]. Revue Neurologique 164 (8–9): 701–721.

- ↑ (December 2018) Sleep disorders in patients with ADHD: impact and management challenges. Nature and Science of Sleep 10: 453–480.

- ↑ (September 2022) Distinct brain structural abnormalities in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and substance use disorders: A comparative meta-analysis. Translational Psychiatry 12 (1): 368.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2009). "Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder", Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People and Adults, NICE Clinical Guidelines. Leicester: British Psychological Society, 18–26, 38. ISBN 978-1-85433-471-8.

- ↑ (February 2016)Association Between Insecure Attachment and ADHD: Environmental Mediating Factors. Journal of Attention Disorders 20 (2): 187–196.

- ↑ (January 2014)Sluggish cognitive tempo (concentration deficit disorder?): current status, future directions, and a plea to change the name. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 42 (1): 117–125.

- ↑ (December 2016)The risk of eating disorders comorbid with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The International Journal of Eating Disorders 49 (12): 1045–1057.

- ↑ (2019) Adverse Childhood Experiences and Family Resilience Among Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics 40 (8): 573–580.

- ↑ (January 2021) Association between Maternal Adverse Childhood Experiences and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in the Offspring: The Mediating Role of Antepartum Health Risks. Soa—Ch'ongsonyon Chongsin Uihak = Journal of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 32 (1): 28–34.

- ↑ (1 June 2009) ADHD and post-traumatic stress disorder. Current Attention Disorders Reports 1 (2): 60–66.

- ↑ (August 2012) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder comorbidity in a sample of veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Comprehensive Psychiatry 53 (6): 679–690.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 (1 January 2011) Trauma and ADHD – Association or Diagnostic Confusion? A Clinical Perspective. Journal of Infant, Child, and Adolescent Psychotherapy 10 (1): 51–59.

- ↑ (October 2022) Understanding the association between adverse childhood experiences and subsequent attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Brain and Behavior 12 (10): e32748.

- ↑ (June 2019) Ecological model of school engagement and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-aged children. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 28 (6): 795–805.

- ↑ (5 January 2021) Childhood ADHD Symptoms in Relation to Trauma Exposure and PTSD Symptoms Among College Students: Attending to and Accommodating Trauma. Journal of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders 29 (3): 187–196.

- ↑ (2016) Epilepsy and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: links, risks, and challenges. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment 12: 287–296.

- ↑ (March 1996) Carbamazepine use in children and adolescents with features of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a meta-analysis. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 35 (3): 352–358.

- ↑ (February 2018) Adult ADHD and Comorbid Somatic Disease: A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Attention Disorders 22 (3): 203–228.

- ↑ (May 2022) The Association between ADHD and Celiac Disease in Children. Children 9 (6).

- ↑ (May 2022) Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and risk of migraine: A nationwide longitudinal study. Headache 62 (5): 634–641.

- ↑ (March 2018) ADHD is associated with migraine: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 27 (3): 267–277.

- ↑ (January 2022) Headache in ADHD as comorbidity and a side effect of medications: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine 52 (1): 14–25.

- ↑ (November 2021) ADHD symptoms in neurometabolic diseases: Underlying mechanisms and clinical implications. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 132: 838–856.

- ↑ (March 2017) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and suicide: A systematic review. World Journal of Psychiatry 7 (1): 44–59.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 (21 December 2020) Long-Term Suicide Risk of Children and Adolescents With Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorder-A Systematic Review. Frontiers in Psychiatry 11. 557909.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 (August 2019)Association between suicidal spectrum behaviors and Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 103: 109–118.

- ↑ (September 2020) ADHD, financial distress, and suicide in adulthood: A population study. Science Advances 6 (40): eaba1551. eaba1551.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 61.4 Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (Easy-to-Read). National Institute of Mental Health (2013).

- ↑ (October 2018) Live fast, die young? A review on the developmental trajectories of ADHD across the lifespan. European Neuropsychopharmacology 28 (10): 1059–1088.

- ↑ (2021-09-01) The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 Evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 128: 789–818.

- ↑ (April 2019) Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Molecular Psychiatry 24 (4): 562–575.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 (2010) "Chapter 2: Causative Factors", Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Handbook: A Physician's Guide to ADHD, 2nd, New York, NY: Springer Science. DOI:10.1007/978-1-4419-1397-5. ISBN 978-1-4419-1396-8.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 (January 2013) What have we learnt about the causes of ADHD?. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 54 (1): 3–16.

- ↑ (March 2015) Annual research review: Rare genotypes and childhood psychopathology—uncovering diverse developmental mechanisms of ADHD risk. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 56 (3): 251–273.

- ↑ (1999). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (adhd) as a noradrenergic disorder. Biological Psychiatry 46 (9): 1234–1242.

- ↑ (2019). Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Molecular Psychiatry 24 (4): 562–575.

- ↑ Baron-Cohen, Simon (2002). The extreme male brain theory of autism. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 6 (6): 248–254.

- ↑ (2005) "32. Evolutionary Psychology and Mental Health", The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, 1st, Wiley. ISBN 978-0471264033.

- ↑ (2016) "43. Evolutionary Psychology and Mental Health", The Handbook of Evolutionary Psychology, Volume 2: Integrations, 2nd, Wiley. ISBN 978-1118755808.

- ↑ (April 2019) Genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Molecular Psychiatry 24 (4): 562–575.

- ↑ (September 2021) The World Federation of ADHD International Consensus Statement: 208 Evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 128: 789–818.

- ↑ (2013) Abnormal Psychology, 6th, McGraw-Hill Education. ISBN 978-0-07-803538-8.

- ↑ (May 2018) Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Controversy, Developmental Mechanisms, and Multiple Levels of Analysis. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology 14 (1): 291–316.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 (December 2011) Neuropsychological endophenotypes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review of genetic association studies. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience 261 (8): 583–594.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedBerry_2007 - ↑ (August 2009) Trace amine-associated receptors as emerging therapeutic targets. Molecular Pharmacology 76 (2): 229–235.

- ↑ (July 2009) Candidate gene studies of ADHD: a meta-analytic review. Human Genetics 126 (1): 51–90.

- ↑ (November 2010) Toward a better understanding of ADHD: LPHN3 gene variants and the susceptibility to develop ADHD. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders 2 (3): 139–147.

- ↑ (June 2010) ADHD and the DRD4 exon III 7-repeat polymorphism: an international meta-analysis. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience 5 (2–3): 188–193.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 83.2 (February 2020) Genetics of ADHD: What Should the Clinician Know?. Current Psychiatry Reports 22 (4).

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 (12 February 2020) Recent advances in understanding of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): how genetics are shaping our conceptualization of this disorder. F1000Research 8.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedSonu_2013 - ↑ CDC (16 March 2016). Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- ↑ (September 2011) Einfluss des mütterlichen Alkoholkonsums während der Schwangerschaft auf die Entwicklung von ADHS beim Kind. Fortschritte der Neurologie-Psychiatrie 79 (9): 500–506.

- ↑ (December 2010) Lead and PCBs as risk factors for attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Environmental Health Perspectives 118 (12): 1654–1667.

- ↑ (August 2012) Does perinatal exposure to endocrine disruptors induce autism spectrum and attention deficit hyperactivity disorders? Review. Acta Paediatrica 101 (8): 811–818.

- ↑ (April 2012) Smoking during pregnancy: lessons learned from epidemiological studies and experimental studies using animal models. Critical Reviews in Toxicology 42 (4): 279–303.

- ↑ (October 2014) Prenatal nicotine exposure and child behavioural problems. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 23 (10): 913–929.

- ↑ (November 1997)Attention deficit hyperactivity disorders and other psychiatric outcomes in very low birthweight children at 12 years. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 38 (8): 931–941.

- ↑ (March 2012) What causes attention deficit hyperactivity disorder?. Archives of Disease in Childhood 97 (3): 260–265.

- ↑ (February 2008) Etiologic classification of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 121 (2): e358–e365.

- ↑ (April 2012) ADHD: an integration with pediatric traumatic brain injury. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics 12 (4): 475–483.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedErk_2009 - ↑ 97.0 97.1 (February 2012)The diet factor in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 129 (2): 330–337.

- ↑ "Food Additives – General". Encyclopedia of Food Safety (1st) 3: box|ambox}} 449–54. (2014). Amsterdam: Elsevier/Academic Press.

- ↑ Background Document for the Food Advisory Committee: Certified Color Additives in Food and Possible Association with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (March 2011).

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNigg_2014 - ↑ (2014). Media use and ADHD-related behaviors in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology 50 (9): 2228–41.

- ↑ (2 October 2018) Screen media use and ADHD-related behaviors: Four decades of research. PNAS USA 115 (40): 9875–9881.

- ↑ (17 July 2018)Association of Digital Media Use With Subsequent Symptoms of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Among Adolescents. JAMA 320 (3): 255–263.

- ↑ Chatterjee, Rhitu, "More Screen Time For Teens Linked To ADHD Symptoms", Morning Edition, NPR, 17 July 2018.

- ↑ Clopton, Jennifer, "ADHD Rising in the U.S., but Why?", Internet Brands, 20 November 2018.

- ↑ (17 April 2019) Screen-time is associated with inattention problems in preschoolers: Results from the CHILD birth cohort study. PLOS One 14 (4).

- ↑ (2020). Digital screen time and its effect on preschoolers' behavior in China: results from a cross-sectional study. Italian Journal of Pediatrics 46 (9).

- ↑ (2020). Screen time in 36-month-olds at increased likelihood for ASD and ADHD. Infant Behavior and Development 61.

- ↑ (2015). A television in the bedroom is associated with higher weekday screen time among youth with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD/ADHD). Preventive Medicine Reports 2: 1–3.

- ↑ (2021). Screen exposure exacerbates ADHD symptoms indirectly through increased sleep disturbance. Sleep Medicine 83: 241–247.

- ↑ (November 2019) Relative age and ADHD symptoms, diagnosis and medication: a systematic review. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 28 (11): 1417–1429.

- ↑ (2013) Disorders of Childhood: Development and Psychopathology. Cengage Learning, 151. ISBN 978-1-285-09606-3.

- ↑ (2016) Year Book of Pediatrics 2014 E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 9780323265270.

- ↑ Mental health of children and adolescents (15 January 2005).

- ↑ 115.0 115.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedNICE 2009 - ↑ 116.0 116.1 116.2 116.3 116.4 116.5 116.6 116.7 (2009) "Chapter 6: Widely Projecting Systems: Monoamines, Acetylcholine, and Orexin", Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience, 2nd, New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 148, 154–157. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4. “DA has multiple actions in the prefrontal cortex. It promotes the 'cognitive control' of behavior: the selection and successful monitoring of behavior to facilitate attainment of chosen goals. Aspects of cognitive control in which DA plays a role include working memory, the ability to hold information 'on line' in order to guide actions, suppression of prepotent behaviors that compete with goal-directed actions, and control of attention and thus the ability to overcome distractions. Cognitive control is impaired in several disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. ... Noradrenergic projections from the LC thus interact with dopaminergic projections from the VTA to regulate cognitive control. ... it has not been shown that 5HT makes a therapeutic contribution to treatment of ADHD.”

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology 64: 135–168.

- ↑ (July 1990) Family-genetic and psychosocial risk factors in DSM-III attention deficit disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 29 (4): 526–533.

- ↑ (2006) Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment. New York: Guilford, 42–5. ISBN 978-1-60623-750-2.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 120.2 120.3 120.4 120.5 120.6 120.7 (2009) "Chapters 10 and 13", Molecular Neuropharmacology: A Foundation for Clinical Neuroscience, 2nd, New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 266, 315, 318–323. ISBN 978-0-07-148127-4. “Early results with structural MRI show thinning of the cerebral cortex in ADHD subjects compared with age-matched controls in prefrontal cortex and posterior parietal cortex, areas involved in working memory and attention.”

- ↑ 121.0 121.1 121.2 (May 2014) New perspectives on catecholaminergic regulation of executive circuits: evidence for independent modulation of prefrontal functions by midbrain dopaminergic and noradrenergic neurons. Frontiers in Neural Circuits 8.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 122.2 (January 2012) Large-scale brain systems in ADHD: beyond the prefrontal-striatal model. Trends in Cognitive Sciences 16 (1): 17–26.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 123.2 (October 2012) Toward systems neuroscience of ADHD: a meta-analysis of 55 fMRI studies. The American Journal of Psychiatry 169 (10): 1038–1055.

- ↑ (August 2006) Brain development and ADHD. Clinical Psychology Review 26 (4): 433–444.

- ↑ (April 2017) Subcortical brain volume differences in participants with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adults: a cross-sectional mega-analysis. The Lancet. Psychiatry 4 (4): 310–319.

- ↑ (February 2018) Hemispheric brain asymmetry differences in youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. NeuroImage: Clinical 18: 744–752.

- ↑ (April 2021) Beneath the surface: hyper-connectivity between caudate and salience regions in ADHD fMRI at rest. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 30 (4): 619–631.

- ↑ 128.0 128.1 (December 2022) Centrality and interhemispheric coordination are related to different clinical/behavioral factors in attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a resting-state fMRI study. Brain Imaging and Behavior 16 (6): 2526–2542.

- ↑ (2015) Brain lateralization and self-reported symptoms of ADHD in a population sample of adults: a dimensional approach. Frontiers in Psychology 6: 1418.

- ↑ (March 2012) Striatal dopamine transporter alterations in ADHD: pathophysiology or adaptation to psychostimulants? A meta-analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry 169 (3): 264–272.

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedcognition enhancers - ↑ (September 2012) The neurobiology and genetics of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): what every clinician should know. European Journal of Paediatric Neurology 16 (5): 422–433.

- ↑ (June 2013) Dances with black widow spiders: dysregulation of glutamate signalling enters centre stage in ADHD. European Neuropsychopharmacology 23 (6): 479–491.

- ↑ (February 2017) Long-Term Memory Performance in Adult ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders 21 (4): 267–283.

- ↑ (July 2013) Are motivation deficits underestimated in patients with ADHD? A review of the literature. Postgraduate Medicine 125 (4): 47–52.

- ↑ Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (March 2016).

- ↑ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2019). Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis and management, NICE Guideline, No. 87. London: National Guideline Centre (UK). ISBN 978-1-4731-2830-9. OCLC 1126668845.

- ↑ Canadian ADHD Practice Guidelines. Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance.

- ↑ Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Recommendations. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (24 June 2015).

- ↑ (October 2019) Clinical Practice Guideline for the Diagnosis, Evaluation, and Treatment of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Pediatrics 144 (4): e20192528.

- ↑ (September 2012) A systematic review and analysis of long-term outcomes in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effects of treatment and non-treatment. BMC Medicine 10.

- ↑ (March 2009) A meta-analysis of behavioral treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Psychology Review 29 (2): 129–140.

- ↑ (March 2009) Review of pediatric attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder for the general psychiatrist. The Psychiatric Clinics of North America 32 (1): 39–56.

- ↑ (March 2018) Cognitive-behavioural interventions for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in adults. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2018 (3): CD010840.

- ↑ (2014) Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology 43 (4): 527–551.

- ↑ (March 2019) Sustained effects of neurofeedback in ADHD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 28 (3): 293–305.

- ↑ (May 2019) Neurofeedback as a Treatment Intervention in ADHD: Current Evidence and Practice. Current Psychiatry Reports 21 (6): 46.

- ↑ (September 2018)Practitioner Review: Current best practice in the use of parent training and other behavioural interventions in the treatment of children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines 59 (9): 932–947.

- ↑ (April 2005) Family therapy for attention-deficit disorder or attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD005042.

- ↑ box|ambox}} "Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)". The Encyclopedia of the Brain and Brain Disorders: 47. (2009). Infobase Publishing.

- ↑ (June 2010) The importance of friendship for youth with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review 13 (2): 181–198.

- ↑ (January 2009) Evolution of stimulants to treat ADHD: transdermal methylphenidate. Human Psychopharmacology 24 (1): 1–17.

- ↑ (February 1995) Origin of stimulant use for treatment of attention deficit disorder. The American Journal of Psychiatry 152 (2): 298–299.

- ↑ (1998) Charles Bradley, M.D.. American Journal of Psychiatry 155 (7).

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedDodson_2005 - ↑ (27 March 2023) Methylphenidate for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2023 (3): CD009885.

- ↑ 157.0 157.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedCNS09 - ↑ 158.0 158.1 (January 2018) Risk of unintentional injuries in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact of ADHD medications: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews 84: 63–71.

- ↑ (February 2013) Meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies of inhibition and attention in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: exploring task-specific, stimulant medication, and age effects. JAMA Psychiatry 70 (2): 185–198.

- ↑ (September 2013) Effect of psychostimulants on brain structure and function in ADHD: a qualitative literature review of magnetic resonance imaging-based neuroimaging studies. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 74 (9): 902–917.

- ↑ (February 2012) Meta-analysis of structural MRI studies in children and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder indicates treatment effects. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 125 (2): 114–126.

- ↑ (September 2018) Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet. Psychiatry 5 (9): 727–738.

- ↑ (February 2019) Efficacy, Acceptability, and Tolerability of Lisdexamfetamine, Mixed Amphetamine Salts, Methylphenidate, and Modafinil in the Treatment of Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 53 (2): 121–133.

- ↑ (October 2002) Comparative Efficacy of Adderall and Methylphenidate in Attention-deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: A Meta-Analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology 22 (5): 468–473.

- ↑ (1 April 2022) Stimulant Induced Movement Disorders in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Journal of the Korean Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 33 (2): 27–34.

- ↑ (March 2012) Revisiting clonidine: an innovative add-on option for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Drugs of Today 48 (3): 207–217.

- ↑ (January 2016) Guanfacine Extended Release: A New Pharmacological Treatment Option in Europe. Clinical Drug Investigation 36 (1): 1–25.

- ↑ (January 2008) A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of guanfacine extended release in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics 121 (1): e73–84.

- ↑ (February 2008) Clonidine for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: I. Efficacy and Tolerability Outcomes. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 47 (2): 180–188.

- ↑ (July 2014)Exercise reduces the symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and improves social behaviour, motor skills, strength and neuropsychological parameters. Acta Paediatrica 103 (7): 709–714.

- ↑ (September 2013) Protection from genetic diathesis in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: possible complementary roles of exercise. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 52 (9): 900–910.

- ↑ 172.0 172.1 (February 2017) Sweat it out? The effects of physical exercise on cognition and behavior in children and adults with ADHD: a systematic literature review. Journal of Neural Transmission 124 (Suppl 1): 3–26.

- ↑ (2008). A felnottkori figyelemhiányos/hiperaktivitás-zavarban tapasztalható neuropszichológiai deficit: irodalmi áttekintés. Psychiatria Hungarica 23 (5): 324–335. PsycNET 2008-18348-001.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedArt.218 - ↑ (August 2015) Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nature Reviews. Disease Primers 1.

- ↑ (October 2008) ADHD and smoking: from genes to brain to behavior. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1141 (1): 131–147.

- ↑ 177.0 177.1 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedMay_2008 - ↑ (February 2006) Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: legal and ethical aspects. Archives of Disease in Childhood 91 (2): 192–194.

- ↑ (February 2005) The scientific foundation for understanding attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder as a valid psychiatric disorder. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 14 (1): 1–10.

- ↑ "Hyperactive children may have genetic disorder, says study", 30 September 2010.

- ↑ (October 2008) Attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a review and update. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 23 (5): 345–357.

- ↑ National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health (2009). "Diagnosis", Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: Diagnosis and Management of ADHD in Children, Young People and Adults, NICE Clinical Guidelines. Leicester: British Psychological Society, 116–7, 119. ISBN 978-1-85433-471-8.

- ↑ "The Selling of Attention Deficit Disorder", 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedGinsberg_2014 - ↑ (September 2010) The importance of relative standards in ADHD diagnoses: evidence based on exact birth dates. Journal of Health Economics 29 (5): 641–656.

- ↑ (May 2015) Misdiagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: 'Normal behaviour' and relative maturity. Paediatrics & Child Health 20 (4): 200–202.