Satyagraha

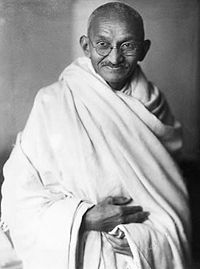

Satyagraha (Sanskrit: सत्याग्रह satyāgraha) is a variety of nonviolent resistance developed by Mohandas Gandhi. Gandhi deployed satyagraha in campaigns for Indian independence and also during his struggles in South Africa. Satyagraha theory also influenced Martin Luther King Jr. during the campaigns he led during the Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

Meaning of the term

Satya is the Sanskrit word for “truth,” and graha (from the Sanskrit root grah cognate with English word “grab”) can be rendered as “effort/endeavor.” The term was popularized during the Indian Independence Movement, and is used in many Indian languages including Hindi.

Gandhi described it as follows:

Its root meaning is holding on to truth, hence truth-force. I have also called it Love-force or Soul-force. In the application of Satyagraha I discovered in the earliest stages that pursuit of truth did not admit of violence being inflicted on one’s opponent but that he must be weaned from error by patience and sympathy. For what appears to be truth to the one may appear to be error to the other. And patience means self-suffering. So the doctrine came to mean vindication of truth not by infliction of suffering on the opponent but on one’s self.[1]

Origins of satyagraha

Gandhi coined the term Satyagraha to describe his philosophy of nonviolent resistance. Speaking of his initial satyagraha campaign in South Africa, he said:

None of us knew what name to give to our movement. I then used the term “passive resistance” in describing it. I did not quite understand the implications of “passive resistance” as I called it. I only knew that some new principle had come into being. As the struggle advanced, the phrase “passive resistance” gave rise to confusion and it appeared shameful to permit this great struggle to be known only by an English name. Again, that foreign phrase could hardly pass as current coin among the community. A small prize was therefore announced in Indian Opinion to be awarded to the reader who invented the best designation for our struggle. We thus received a number of suggestions. The meaning of the struggle had been then fully discussed in Indian Opinion and the competitors for the prize had fairly sufficient material to serve as a basis for their exploration. Shri Maganlal Gandhi was one of the competitors and he suggested the word sadagraha, meaning “firmness in a good cause.” I liked the word, but it did not fully represent the whole idea I wished it to connote. I therefore corrected it to “satyagraha”. Truth (satya) implies love, and firmness (agraha) engenders and therefore serves as a synonym for force. I thus began to call the Indian movement Satyagraha, that is to say, the Force which is born of Truth and Love or non-violence, and gave up the use of the phrase “passive resistance”, in connection with it, so much so that even in English writing we often avoided it and used instead the word “satyagraha” itself or some other equivalent English phrase.[2]

Contrast to “passive resistance”

Gandhi further distinguished between his ideas and passive resistance:

I have drawn the distinction between passive resistance as understood and practised in the West and satyagraha before I had evolved the doctrine of the latter to its full logical and spiritual extent. I often used “passive resistance” and “satyagraha” as synonymous terms: but as the doctrine of satyagraha developed, the expression “passive resistance” ceases even to be synonymous, as passive resistance has admitted of violence as in the case of suffragettes and has been universally acknowledged to be a weapon of the weak. Moreover, passive resistance does not necessarily involve complete adherence to truth under every circumstance. Therefore it is different from satyagraha in three essentials: Satyagraha is a weapon of the strong; it admits of no violence under any circumstance whatever; and it ever insists upon truth. I think I have now made the distinction perfectly clear.[3]

Influences

In developing satyagraha, Gandhi was influenced by earlier theorists of nonviolence as expounded in the concept of ahimsa in the Hindu Upanishads and the tenets of Jainism, as well as nonviolent resistance and nonresistance including Jesus (particularly the Sermon on the Mount), Leo Tolstoy (particularly The Kingdom of God Is Within You), John Ruskin (particularly Unto This Last), and Henry David Thoreau (particularly Civil Disobedience).[4]

Satyagraha theory

Defining success

In traditional violent and nonviolent conflict, the goal is to defeat the opponent or frustrate the opponent’s objectives, or to meet one’s own objectives despite the efforts of the opponent to obstruct these. In satyagraha, by contrast, these are not the goals. “The Satyagrahi’s object is to convert, not to coerce, the wrong-doer.”[5] Success is defined as cooperating with the opponent to meet a just end that the opponent is unwittingly obstructing. The opponent must be converted, at least as far as to stop obstructing the just end, for this cooperation to take place.

Means and ends

The theory of satyagraha sees means and ends as inseparable. The means used to obtain an end are wrapped up and attached to that end. Therefore, it is contradictory to try to use unjust means to obtain justice or to try to use violence to obtain peace. Gandhi used an example to explain this:

If I want to deprive you of your watch, I shall certainly have to fight for it; if I want to buy your watch, I shall have to pay for it; and if I want a gift, I shall have to plead for it; and, according to the means I employ, the watch is stolen property, my own property, or a donation.[6]

Gandhi rejected the idea that injustice should, or even could, be fought against “by any means neccessary” — if you use violent, coercive, unjust means, whatever ends you produce will necessarily embed that injustice.

Satyagraha and its offshoots, non-cooperation and civil disobedience, are based on the “law of suffering”[7], a doctrine that the endurance of suffering is a means to an end. This end usually implies a moral upliftment or progress of an individual or society. Therefore, non-cooperation in Satyagraha is in fact a means to secure the cooperation of the opponent consistently with truth and justice.

The essence of non-violent resistance is that it seeks to eliminate antagonisms without harming the antagonists themselves, as opposed to violent resistance, which is meant to cause harm to the antagonist. A Satyagrahi therefore does not seek to end or destroy the relationship with the antagonist, but instead seeks to transform or “purify” it to a higher level. A euphemism sometimes used for Satyagraha is that it is a “silent force” or a “soul force” (a term also used by Martin Luther King Jr. during his famous “I Have a Dream” speech). It arms the individual with moral power rather than physical power. Satyagraha is also termed a “universal force,” as it essentially “makes no distinction between kinsmen and strangers, young and old, man and woman, friend and foe.”[8]

Satyagraha in large-scale conflict

Civil obedience as a prerequisite

When using satyagraha in a large-scale political conflict involving civil disobedience, Gandhi believed that the satyagrahis must

- appreciate the other laws of the State and obey them voluntarily

- tolerate these laws, even when they are inconvenient

- be willing to undergo suffering, loss of property, and to endure the suffering that might be inflicted on family and friends

and that they must undergo training, as necessary, to ensure that they have this discipline.[9]

Civil disobedience cannot stem from irresponsibility: “only when a people have proved their active loyalty by obeying the many laws of the State that they acquire the right of Civil Disobedience.”[9]

This obedience has to be not merely grudging, but extraordinary:

…an honest, respectable man will not suddenly take to stealing whether there is a law against stealing or not, but this very man will not feel any remorse for failure to observe the rule about carrying headlights on bicycles after dark.… But he would observe any obligatory rule of this kind, if only to escape the inconvenience of facing a prosecution for a breach of the rule. Such compliance is not, however, the willing and spontaneous obedience that is required of a Satyagrahi.[10]

Rules

Gandhi proposed a series of rules for satyagrahis to follow in a resistance campaign:[8]

- harbour no anger

- suffer the anger of the opponent

- never retaliate to assaults or punishment; but do not submit, out of fear of punishment or assault, to an order given in anger

- voluntarily submit to arrest or confiscation of your own property

- if you are a trustee of property, defend that property (non-violently) from confiscation with your life

- do not curse or swear

- do not insult the opponent

- neither salute nor insult the flag of your opponent or your opponent’s leaders

- if anyone attempts to insult or assault your opponent, defend your opponent (non-violently) with your life

- as a prisoner, behave courteously and obey prison regulations (except any that are contrary to self-respect)

- as a prisoner, do not ask for special favourable treatment

- as a prisoner, do not fast in an attempt to gain conveniences whose deprivation does not involve any injury to your self-respect

- joyfully obey the orders of the leaders of the civil disobedience action

- do not pick and choose amongst the orders you obey; if you find the action as a whole improper or immoral, sever your connection with the action entirely

- do not make your participation conditional on your comrades taking care of your dependants while you are engaging in the campaign or are in prison; do not expect them to provide such support

- do not become a cause of communal quarrels

- do not take sides in such quarrels, but assist only that party which is demonstrably in the right; in the case of inter-religious conflict, give your life to protect (non-violently) those in danger on either side

- avoid occasions that may give rise to communal quarrels

- do not take part in processions that would wound the religious sensibilities of any community

Application of Satyagraha during WWII

As a rule, Gandhi was opposed to the concept of partition as it contradicted his vision of religious unity.[11] As he had with the partition of India to create Pakistan, Gandhi expressed his dislike for partition during the late 1930s in response to the topic of the partition of Palestine to create Israel. He stated in Harijan on 26 October, 1938:

- Several letters have been received by me asking me to declare my views about the Arab-Jew question in Palestine and persecution of the Jews in Germany. It is not without hesitation that I venture to offer my views on this very difficult question. My sympathies are all with the Jews. I have known them intimately in South Africa. Some of them became life-long companions. Through these friends I came to learn much of their age-long persecution. They have been the untouchables of Christianity [...] But my sympathy does not blind me to the requirements of justice. The cry for the national home for the Jews does not make much appeal to me. The sanction for it is sought in the Bible and the tenacity with which the Jews have hankered after return to Palestine. Why should they not, like other peoples of the earth, make that country their home where they are born and where they earn their livelihood? Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the English or France to the French. It is wrong and inhuman to impose the Jews on the Arabs. What is going on in Palestine today cannot be justified by any moral code of conduct.[12][13]

He continued this argument in a number of articles reprinted in Homer Jack's The Gandhi Reader: A Sourcebook of His Life and Writings. In the first, "Zionism and Anti-Semitism," written in 1938, Gandhi commented upon the 1930s persecution of the Jews in Germany within the context of Satyagraha. He offered non-violence as a method of combating the difficulties Jews faced in Germany, stating,

- If I were a Jew and were born in Germany and earned my livelihood there, I would claim Germany as my home even as the tallest Gentile German might, and challenge him to shoot me or cast me in the dungeon; I would refuse to be expelled or to submit to discriminating treatment. And for doing this I should not wait for the fellow Jews to join me in civil resistance, but would have confidence that in the end the rest were bound to follow my example. If one Jew or all the Jews were to accept the prescription here offered, he or they cannot be worse off than now. And suffering voluntarily undergone will bring them an inner strength and joy [...] the calculated violence of Hitler may even result in a general massacre of the Jews by way of his first answer to the declaration of such hostilities. But if the Jewish mind could be prepared for voluntary suffering, even the massacre I have imagined could be turned into a day of thanksgiving and joy that Jehovah had wrought deliverance of the race even at the hands of the tyrant. For to the God-fearing, death has no terror.[14]

Gandhi was highly criticized for these statements and responded in the article "Questions on the Jews" with "Friends have sent me two newspaper cuttings criticizing my appeal to the Jews. The two critics suggest that in presenting non-violence to the Jews as a remedy against the wrong done to them, I have suggested nothing new....what I have pleaded for is renunciation of violence of the heart and consequent active exercise of the force generated by the great renunciation. [15] He responded to the criticisms in "Reply to Jewish Friends"[16] and "Jews and Palestine."[17] by arguing that "What I have pleaded for is renunciation of violence of the heart and consequent active exercise of the force generated by the great renunciation."[18]

In a similar vein, anticipating a possible attack on India by Japan during World War II, Gandhi recommended satyagraha as a defense:

…there should be unadulterated non-violent non-cooperation, and if the whole of India responded and unanimously offered it, I should show that, without shedding a single drop of blood, Japanese arms – or any combination of arms – can be sterilized. That involves the determination of India not to give quarter on any point whatsoever and to be ready to risk loss of several million lives. But I would consider that cost very cheap and victory won at that cost glorious. That India may not be ready to pay that price may be true. I hope it is not true, but some such price must be paid by any country that wants to retain its independence. After all, the sacrifice made by the Russians and the Chinese is enormous, and they are ready to risk all. The same could be said of the other countries also, whether aggressors or defenders. The cost is enormous. Therefore, in the non-violent technique I am asking India to risk no more than other countries are risking and which India would have to risk even if she offered armed resistance.[19]

Satyagraha vows

Gandhi envisioned satyagraha as not only a tactic to be used in acute political struggle, but as a universal solvent for injustice and harm. He felt that it was equally applicable to large-scale political struggle and to one-on-one interpersonal conflicts and that it should be taught to everyone.[20]

He founded the Sabarmati Ashram to teach satyagraha. He asked satyagrahis to follow the following principles:[21]

- Nonviolence (ahimsa)

- Truth — this includes honesty, but goes beyond it to mean living fully in accord with and in devotion to that which is true

- Non-stealing

- Chastity (brahmacharya) — this includes sexual chastity, but also the subordination of other sensual desires to the primary devotion to truth

- Non-possession (poverty)

- Body-labor or bread-labor

- Control of the palate

- Fearlessness

- Equal respect for all religions

- Swadeshi

- Freedom from untouchability

On another occasion, he listed seven rules as “essential for every Satyagrahi in India”:[22]

- must have a living faith in God

- must believe in truth and non-violence and have faith in the inherent goodness of human nature which he expects to evoke by suffering in the satyagraha effort

- must be leading a chaste life, and be willing to die or lose all his possessions

- must be a habitual khadi wearer and spinner

- must abstain from alcohol and other intoxicants

- must willingly carry out all the rules of discipline that are issued

- must obey the jail rules unless they are specially devised to hurt his self respect

Gandhi’s definition of Satyagraha relied on three basic tenets: satya or truth, implying openness, honesty, and fairness; ahimsa, meaning physical and mental non-violence; and tapasya, literally penance, in this context self-sacrifice.

The Satyagrahi is meant to practice self-effacement, humility, patience and faith. Fasting is seen as a powerful tool to achieve personal self-restraint that can be projected outwards to show determination and courage.

Gandhi wrote:

Satyagraha presupposes self-discipline, self-control, self-purification, and a recognized social status in the person offering it. A Satyagrahi must never forget the distinction between evil and the evil-doer. He must not harbour ill-will or bitterness against the latter. He may not even employ needlessly offensive language against the evil person, however unrelieved his evil might be. For it should be an article of faith with every Satyagrahi that there is none so fallen in this world but can be converted by love. A Satyagrahi will always try to overcome evil by good, anger by love, untruth by truth, himsa by ahimsa.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Gandhi, M.K. Non-violent Resistance (Satyagraha) (1961) p. 6

- ↑ Gandhi, M.K. “The Advent of Satyagraha” (chapter 12 of Satyagraha in South Africa, 1926)

- ↑ Gandhi, M.K. “Letter to Mr. ——” 25 January 1920 (The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi vol. 19, p. 350)

- ↑ Gandhi, M.K. Non-violent Resistance (Satyagraha) (1961) p. iii

- ↑ Gandhi, M.K. “Requisite Qualifications” Harijan 25 March 1939

- ↑ Gandhi, M.K. Non-violent Resistance (Satyagraha) (1961) p. 11

- ↑ Gandhi, M.K. “The Law of Suffering” Young India 16 June 1920

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Gandhi, M.K. “Some Rules of Satyagraha” Young India (Navajivan) 27 February 1930

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Gandhi, M.K. “Pre-requisites for Satyagraha” Young India 1 August 1925

- ↑ Gandhi, M.K. “A Himalayan Miscalculation” in The Story of My Experiments with Truth Chapter 33

- ↑ reprinted in The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas., Louis Fischer, ed., 2002 (reprint edition) pp. 106–108.

- ↑ reprinted in The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas., Louis Fischer, ed., 2002 (reprint edition) pp. 286-288.

- ↑ http://lists.ifas.ufl.edu/cgi-bin/wa.exe?A2=ind0109&L=sanet-mg&P=31587.

- ↑ Jack, Homer. The Gandhi Reader, pp. 319–20.

- ↑ Jack, Homer. The Gandhi Reader, p. 322.

- ↑ Jack, Homer. The Gandhi Reader, pp. 323–4.

- ↑ Jack, Homer The Gandhi Reader, pp. 324–6.

- ↑ Jack, Homer. The Gandhi Reader, p. 322.

- ↑ Gandhi, M.K. “Non-violent Non-cooperation” Harijan 24 May 1942, p. 167

- ↑ Gandhi, M.K. “The Theory and Practice of Satyagraha” Indian Opinion 1914

- ↑ Gandhi, M.K. Non-violent Resistance (Satyagraha) (1961) p. 37

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Gandhi, M.K. “Qualifications for Satyagraha” Young India 8 August 1929

See also

- Non-violence

- Gandhism

- David McReynolds

- Civil Disobedience

- Christian nonviolence

- Deep Democracy

- Mohandas Gandhi

- Indian Independence Movement

- Martin Luther King Jr.

| |||||||||||

de:Satyagraha eo:Satyagraha es:Satyagraha fr:Satyagraha ko:사티아그라하 it:Satyagraha he:סאטיאגרהא pt:Satyagraha ru:Сатьяграха fi:Satyagraha sv:Satyagraha

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.