Autism

| Autism Classification and external resources | |

| Obsessively stacking or lining up objects may indicate autism. | |

| ICD-10 | F84.0 |

| ICD-9 | 299.0 |

| OMIM | 209850 |

| DiseasesDB | 1142 |

| MedlinePlus | 001526 |

| eMedicine | med/3202 ped/180 |

| MeSH | D001321 |

Autism is a brain development disorder characterized by impairments in social interaction and communication, and restricted and repetitive behavior, all exhibited before a child is three years old. These characteristics distinguish autism from milder autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Heritability contributes about 90% of the risk of a child's developing the disorder, although the genetics of autism are complex, and it is generally unclear which genes are responsible.[1] In rare cases, autism is strongly associated with agents that cause birth defects.[2] Other proposed causes, such as the exposure of children to vaccines, are controversial and the vaccine hypotheses are unsupported by convincing scientific evidence.[3] Most recent reviews estimate a prevalence of one to two cases per 1,000 people for autism, and about six per 1,000 for ASD, with ASD averaging a 4.3:1 male-to-female ratio. The number of people known to have autism has increased dramatically since the 1980s, at least partly due to changes in diagnostic practice; the question of whether prevalence has increased is unresolved.[4]

Autism affects many parts of the brain; how this occurs is poorly understood. Parents usually notice signs in the first year or two of their child's life. Early intervention may help children gain self-care and social skills, although few of these interventions are supported by scientific studies; there is no cure.[5] With severe autism, independent living is unlikely; with milder autism, there are some success stories for adults,[6] and an autistic culture has developed, with some seeking a cure and others believing that autism is a condition rather than a disorder.[7]

Classification

Autism is a developmental disorder of the human brain that first shows signs during infancy or childhood and follows a steady course without remission or relapse.[8] Impairments result from maturation-related changes in various systems of the brain.[9] Autism is one of the five pervasive developmental disorders (PDD) or autism spectrum disorders (ASD), which are characterized by widespread abnormalities of social interactions and communication, and severely restricted interests and highly repetitive behavior.[8]

Of the other four autism spectrum disorders, Asperger's syndrome is closest to autism in signs and likely causes; Rett syndrome and childhood disintegrative disorder share several signs with autism, but may have unrelated causes; pervasive developmental disorder not otherwise specified (PDD-NOS) is diagnosed when the criteria are not met for a more specific disorder.[10] Unlike autism, Asperger's has no substantial delay in language development.[11] The terminology of autism can be bewildering, with autism, Asperger's and PDD-NOS sometimes called the autistic disorders,[1] whereas autism itself is often called autistic disorder, childhood autism, or infantile autism. In this article, autism refers to the classic autistic disorder, while other sources sometimes use autism to refer to autistic disorders or even ASD. ASD, in turn, is a subset of the broader autism phenotype (BAP), which describes individuals who may not have ASD but do have autistic-like traits, such as avoiding eye contact.[12]

Autism's manifestations cover a wide spectrum, ranging from individuals with severe impairments—who may be silent, mentally disabled, and locked into hand flapping and rocking—to less impaired individuals who may have active but distinctly odd social approaches, narrowly focused interests, and verbose, pedantic communication.[13] Sometimes the syndrome is divided into low-, medium- and high-functioning autism (LFA, MFA, and HFA), based on IQ thresholds,[14] or on how much support the individual requires in daily life; these subdivisions are not standardized and are controversial. Autism can also be divided into syndromal and non-syndromal autism, where the former is associated with severe or profound mental retardation or a congenital syndrome with physical symptoms, such as tuberous sclerosis.[15] Although individuals with Asperger's tend to perform better cognitively than those with autism, the extent of the overlap between Asperger's, HFA, and non-syndromal autism is unclear.[16]

Some studies have reported diagnoses of autism in children due to a loss of language or social skills, as opposed to a failure to make progress. Several terms are used for this phenomenon, including regressive autism, setback autism, and developmental stagnation. The validity of this distinction remains controversial; it is possible that regressive autism is a specific subtype.[17][18]

Characteristics

Autism is distinguished by a pattern of symptoms rather than one single symptom. The main characteristics are impairments in social interaction, impairments in communication, restricted interests and repetitive behavior. Other aspects, such as atypical eating, are also common but are not essential for diagnosis.[19]

Social development

Autistic people have social impairments and often lack the intuition about others that many people take for granted. Noted autistic Temple Grandin described her inability to understand the social communication of neurotypicals as leaving her feeling "like an anthropologist on Mars".[20]

Social impairments become apparent early in childhood and continue through adulthood. Autistic infants show less attention to social stimuli, smile and look at others less often, and respond less to their own name. Autistic toddlers have more striking social deviance; for example, they have less eye contact and anticipatory postures and are less likely to use another person's hand or body as a tool.[18] Three- to five-year-old autistic children are less likely to exhibit social understanding, approach others spontaneously, imitate and respond to emotions, communicate nonverbally, and take turns with others. However, they do form attachments to their primary caregivers.[21] They display moderately less attachment security than usual, although this feature disappears in children with higher mental development or less severe ASD.[22] Older children and adults with ASD perform worse on tests of face and emotion recognition.[23]

Contrary to common belief, autistic children do not prefer to be alone. Making and maintaining friendships often proves to be difficult for those with autism. For them, the quality of friendships, not the number of friends, predicts how lonely they are.[24]

There are many anecdotal reports, but few systematic studies, of aggression and violence in individuals with ASD. The limited data suggest that in children with mental retardation, autism is associated with aggression, destruction of property, and tantrums. Dominick et al. interviewed the parents of 67 children with ASD and reported that about two-thirds of the children had periods of severe tantrums and about one third had a history of aggression, with tantrums significantly more common than in children with a history of language impairment.[25]

Communication

About a third to a half of individuals with autism do not develop enough natural speech to meet their daily communication needs.[26] Differences in communication may be present from the first year of life, and may include delayed onset of babbling, unusual gestures, diminished responsiveness, and the desynchronization of vocal patterns with the caregiver. In the second and third years, autistic children have less frequent and less diverse babbling, consonants, words, and word combinations; their gestures are less often integrated with words. Autistic children are less likely to make requests or share experiences, and are more likely to simply repeat others' words (echolalia)[17][27] or reverse pronouns.[28] Autistic children may have difficulty with imaginative play and with developing symbols into language.[17][27] They are more likely to have problems understanding pointing; for example, they may look at a pointing hand instead of the pointed-at object.[18][27]

In a pair of studies, high-functioning autistic children aged 8–15 performed equally well, and adults better than individually matched controls at basic language tasks involving vocabulary and spelling. Both autistic groups performed worse than controls at complex language tasks such as figurative language, comprehension and inference. As people are often sized up initially from their basic language skills, these studies suggest that people speaking to autistic individuals are more likely to overestimate what their audience comprehends.[29]

Repetitive behavior

Autistic individuals display many forms of repetitive or restricted behavior, which the Repetitive Behavior Scale-Revised (RBS-R) categorizes as follows.

- Stereotypy is apparently purposeless movement, such as hand flapping, head rolling, body rocking, or spinning a plate.

- Compulsive behavior is intended and appears to follow rules, such as arranging objects in a certain way.

- Sameness is resistance to change; for example, insisting that the furniture not be moved or refusing to be interrupted.

- Ritualistic behavior involves the performance of daily activities the same way each time, such as an unvarying menu or dressing ritual.

- Restricted behavior is limited in focus, interest, or activity, such as preoccupation with a single television program.

- Self-injury includes movements that injure or can injure the person, such as biting oneself. Dominick et al. reported that self-injury at some point affected about 30% of children with ASD.[25]

No single repetitive behavior is associated with autism, but only autism appears to have an elevated pattern of occurrence and severity of these behaviors.[30]

Other symptoms

Autistic individuals may have symptoms that are independent of the diagnosis, but that can affect the individual or the family.[19] As many as 10% of individuals with ASD show unusual abilities, ranging from splinter skills such as the memorization of trivia to the extraordinarily rare talents of prodigious autistic savants.[31]

Unusual responses to sensory stimuli are more common and prominent in autistic children, although there is no good evidence that sensory symptoms differentiate autism from other developmental disorders.[32] The responses may be more common in children: a pair of studies found that autistic children had impaired tactile perception while autistic adults did not. The same two studies also found that autistic individuals had more problems with complex memory and reasoning tasks such as Twenty Questions; these problems were somewhat more marked among adults.[29] Several studies have reported associated motor problems that include poor muscle tone, poor motor planning, and toe walking; ASD is not associated with severe motor disturbances.[33]

Atypical eating behavior occurs in about three-quarters of children with ASD, to the extent that it was formerly a diagnostic indicator. Selectivity is the most common problem, although eating rituals and food refusal also occur;[25] this does not appear to result in malnutrition. Some children with autism also have gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, but there is a lack of published rigorous data to support the theory that autistic children have more or different GI symptoms than usual.[34]

Sleep problems are known to be more common in children with developmental disabilities, and there is some evidence that children with ASD are more likely to have even more sleep problems than those with other developmental disabilities; autistic children may experience problems including difficulty in falling asleep, frequent nocturnal awakenings, and early morning awakenings. Dominick et al. found that about two-thirds of children with ASD had a history of sleep problems.[25]

Causes

Although many genetic and environmental causes of autism have been proposed, its theory of causation is still incomplete.[35] Some researchers argue this is because autism is not a single disorder, but rather a triad of core aspects (social impairment, communication difficulties, and repetitive behaviors) that have distinct causes but often co-occur.[36]

Genetic factors are the most significant cause for autism spectrum disorders. Early studies of twins estimated heritability to be more than 90%; in other words, that genetics explains more than 90% of autism cases.[1] When only one identical twin is autistic, the other often has learning or social disabilities. For adult siblings, the risk of having one or more features of the broader autism phenotype might be as high as 30%,[37] much higher than the risk in controls.[38]

The genetics of autism is complex.[1] For each autistic individual, mutations in more than one gene may be implicated. Mutations in different sets of genes may be involved in different autistic individuals. There may be significant interactions among mutations in several genes, or between the environment and mutated genes. By identifying genetic markers inherited with autism in family studies, numerous candidate genes have been located, most of which encode proteins involved in neural development and function.[39] However, for most of the candidate genes, the actual mutations that increase the risk for autism have not been identified. Typically, autism cannot be traced to a Mendelian (single-gene) mutation or to a single chromosome abnormality such as fragile X syndrome or 22q13 deletion syndrome.[15][40]

The large number of autistic individuals with unaffected family members may result from copy number variations (CNVs)—spontaneous alterations in the genetic material during meiosis that delete or duplicate genetic material. Sporadic (non-inherited) cases have been examined to identify candidate genetic loci involved in autism. Using array comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH), a technique for detecting CNVs, one study found them in 10% of families with one affected child.[42] Some of the altered loci had been identified in previous studies of inherited autism; many were unique to the sporadic cases examined in this study. Hence, a substantial fraction of autism may be highly heritable but not inherited: that is, the mutation that causes the autism is not present in the parental genome. The fraction of autism traceable to a genetic cause may grow to 30–40% as the resolution of array CGH improves.[41] The Autism Genome Project database contains genetic linkage and CNV data that connect autism to genetic loci and suggest that every human chromosome may be involved.[43]

Teratogens (agents that cause birth defects) related to the risk of autism include exposure of the embryo to thalidomide, valproic acid, or misoprostol, or to rubella infection in the mother. These cases are rare.[44] All known teratogens appear to act during the first eight weeks from conception, and though this does not exclude the possibility that autism can be initiated or affected later, it is strong evidence that autism arises very early in development.[2] Other possible contributors to autism include gastrointestinal or immune system abnormalities, allergies, and the exposure of children to drugs, vaccines, infection, certain foods,[45] or heavy metals; the evidence for these risk factors is anecdotal and has not been confirmed by reliable studies,[3] and extensive further searches are underway.[44] Parents may first become aware of autistic symptoms in their child around the time of a routine vaccination. Although there is overwhelming scientific evidence that there is no causal connection between the measles-mumps-rubella vaccine and autism, or between the vaccine preservative thiomersal and autism, parental concern has led to a decreasing uptake of childhood immunizations and the increasing likelihood of measles outbreaks.[46]

Mechanism

Despite extensive investigation, how autism occurs is not well understood. Its mechanism can be divided into two areas: the pathophysiology of brain structures and processes associated with autism, and the neuropsychological linkages between brain structures and behaviors.[9]

Pathophysiology

Autism appears to result from developmental factors that affect many or all functional brain systems, as opposed to localized physical damage.[40] Many major structures of the human brain have been implicated. Consistent neuroanatomical abnormalities have been found in the development of the cerebral cortex; and in the cerebellum and related inferior olive, which have a significant decrease in the number of Purkinje cells. Brain weight and volume and head circumference tend to be greater in autistic children; the effects of these are unknown.[47] It may be due to poorly regulated growth of neurons.[9]

Interactions between the immune system and the nervous system begin early during embryogenesis, and successful neurodevelopment depends on a balanced immune response. Several symptoms consistent with a poorly regulated immune response have been reported in autistic children. It is possible that aberrant immune activity during critical periods of neurodevelopment is part of the mechanism of some forms of ASD.[48] Given the lack of data in this area, it is still hard to draw conclusions about the role of immune factors in autism.[49]

Several neurotransmitter abnormalities have been detected in autism, notably increased blood levels of serotonin. Whether these lead to structural or behavioral abnormalities is unclear.[9]

The mirror neuron system (MNS) theory of autism hypothesizes that distortion in the development of the MNS interferes with imitation and leads to autism's core features of social impairment and communication difficulties. The MNS operates when an animal performs an action or observes another animal of the same species perform the same action. The MNS may contribute to an individual's understanding of other people by enabling the modeling of their behavior via embodied simulation of their actions, intentions, and emotions.[50] Several studies have tested this hypothesis by demonstrating structural abnormalities in MNS regions of individuals with ASD, delay in the activation in the core circuit for imitation in individuals with Asperger's, and a correlation between reduced MNS activity and severity of the syndrome in children with ASD.[51]

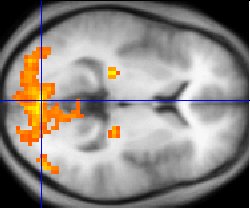

The underconnectivity theory of autism hypothesizes that autism is marked by underfunctioning high-level neural connections and synchronization, along with an excess of low-level processes.[52] Evidence for this theory has been found in functional neuroimaging studies on autistic individuals[29] and by a brain wave study that suggested that adults with ASD have local overconnectivity in the cortex and weak functional connections between the frontal lobe and the rest of the cortex.[53] Other evidence suggests the underconnectivity is mainly within each hemisphere of the cortex and that autism is a disorder of the association cortex.[54]

Neuropsychology

Two major categories of cognitive theories have been proposed about the links between autistic brains and behavior.

The first category focuses on deficits in social cognition. Hyper-systemizing hypothesizes that autistic individuals can systematize—that is, they can develop internal rules of operation to handle internal events—but are less effective at empathizing by handling events generated by other agents.[14] It extends the extreme male brain theory, which hypothesizes that autism is an extreme case of the male brain, defined psychometrically as individuals in whom systemizing is better than empathizing.[55] This in turn is related to the earlier theory of mind, which hypothesizes that autistic behavior arises from an inability to ascribe mental states to oneself and others. The theory of mind is supported by autistic children's atypical responses to the Sally-Anne test for reasoning about others' motivations,[56] and is mapped well from the mirror neuron system theory of autism.[51]

The second category focuses on nonsocial or general processing. Executive dysfunction hypothesizes that autistic behavior results in part from deficits in flexibility, planning, and other forms of executive function. A strength of the theory is predicting stereotyped behavior and narrow interests;[57] a weakness is that executive function deficits are not found in young autistic children.[23] Weak central coherence theory hypothesizes that a limited ability to see the big picture underlies the central disturbance in autism. One strength of this theory is predicting special talents and peaks in performance in autistic people.[58] A related theory—enhanced perceptual functioning—focuses more on the superiority of locally oriented and perceptual operations in autistic individuals.[59] The latter two theories map well from the underconnectivity theory of autism.

Neither category is satisfactory on its own; social cognition theories poorly address autism's rigid and repetitive behaviors, while the nonsocial theories have difficulty explaining social impairment and communication difficulties.[36] A combined theory based on multiple deficits may prove to be more useful.[7]

Screening

Parents are usually the first to notice unusual behaviors in their child.[60] As postponing treatment may affect long-term outcome, any of the following signs is reason to have a child evaluated by a specialist without delay:

- No babbling by 12 months.

- No gesturing (pointing, waving goodbye, etc.) by 12 months.

- No single words by 16 months.

- No two-word spontaneous phrases (not including echolalia) by 24 months.

- Any loss of any language or social skills, at any age.[19]

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that all children be screened for ASD at the 9-, 18-, and 30-month well-child doctor visits, using autism-specific formal screening tests.[61] In contrast, the UK National Screening Committee recommends against screening for ASD in the general population, because screening tools have not been fully validated and interventions lack sufficient evidence for effectiveness.[62]

Genetic screening for autism is generally still impractical. As genetic tests are developed several ethical, legal, and social issues will emerge. Commercial availability of tests may precede adequate understanding of how to use test results, given the complexity of autism's genetics.[63]

Diagnosis

Autism is defined in the DSM-IV-TR as exhibiting at least six symptoms total, including at least two symptoms of qualitative impairment in social interaction, at least one symptom of qualitative impairment in communication, and at least one symptom of restricted and repetitive behavior. Sample symptoms include lack of social or emotional reciprocity, stereotyped and repetitive use of language or idiosyncratic language, and persistent preoccupation with parts of objects. Onset must be prior to age three years, with delays or abnormal functioning in either social interaction, language as used in social communication, or symbolic or imaginative play. The disturbance must not be better accounted for by Rett syndrome or childhood disintegrative disorder.[64] ICD-10 uses essentially the same definition.[8]

Several diagnostic instruments are available. Two are commonly used in autism research: the Autism Diagnostic Interview-Revised (ADI-R) is a semistructured parent interview, and the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule (ADOS) uses observation and interaction with the child. The Childhood Autism Rating Scale (CARS) is used widely in clinical environments to assess severity of autism based on observation of children.[18]

A pediatrician commonly performs a preliminary investigation by taking developmental history and physically examining the child. If warranted, diagnosis and evaluations are conducted with help from ASD specialists, observing and assessing cognitive, communication, family, and other factors using standardized tools, and taking into account any associated medical conditions. A differential diagnosis for ASD at this stage might also consider mental retardation, hearing impairment, and a specific language disorder[65] such as Landau-Kleffner syndrome.[66] In the UK the National Autism Plan for Children recommends at most 30 weeks from first concern to completed diagnosis and assessment, though few cases are handled that quickly in practice.[65] ASD can sometimes be diagnosed by age 14 months,[67] but a 2006 U.S. study found the average age of first evaluation by a qualified professional was 48 months and of formal ASD diagnosis was 61 months, reflecting an average 13-month delay, all far above recommendations.[68]

Underdiagnosis and overdiagnosis are problems in marginal cases, and much of the recent increase in the number of reported ASD cases is likely due to changes in diagnostic practices. The increasing popularity of drug treatment options and the expansion of benefits has given providers incentives to diagnose ASD, resulting in some overdiagnosis of children with uncertain symptoms. Conversely, the cost of screening and diagnosis and the challenge of obtaining payment can inhibit or delay diagnosis.[69] It is particularly hard to diagnose autism among the visually impaired, partly because some of its diagnostic criteria depend on vision, and partly because autistic symptoms overlap with those of common blindness syndromes.[70]

The symptoms of autism and ASD begin early in childhood but are occasionally missed. Adults may seek retrospective diagnoses to help them or their friends and family understand themselves, to help their employers make adjustments, or in some locations to claim disability living allowances or other benefits.[71]

Treatment

The goal of treatment is to manage and improve symptoms and functioning. No single treatment is best and treatment is typically tailored to the child's needs. Intensive, sustained special education programs and behavior therapy early in life can help children acquire self-care, social, and job skills.[72][73] Among the available approaches, applied behavior analysis (ABA) has demonstrated efficacy in promoting social and language development and in reducing behaviors that interfere with learning and cognitive functioning;[73] ABA focuses on teaching tasks one-on-one using the behaviorist principles of stimulus, response and reward.[74] Cognitive therapies based on comprehensive programs in treatment centers are a common alternative: for example, TEACCH focuses on structuring the physical environment and using visual supports for language development tasks.[73] A 2005 California study found that early intensive behavior analytic treatment, a form of ABA, was substantially more effective for preschool children with autism than the mixture of methods provided in many programs.[74] The limited research on the effectiveness of adult residential programs shows mixed results.[75]

Medications are often used to treat problems associated with ASD. More than half of U.S. children diagnosed with ASD are prescribed psychoactive drugs or anticonvulsants, with the most common drug classes being antidepressants, stimulants, and antipsychotics.[76] In the United States, the antipsychotic risperidone is approved for treating symptomatic irritability in autistic children and adolescents.[77] Other drugs are prescribed off-label, which means they have not been approved for treating ASD. For example, serotonin reuptake inhibitors and dopamine blockers can sometimes reduce some symptoms.[9] However, there is scant reliable research about the effectiveness or safety of drug treatments for adolescents and adults with ASD.[78] A person with ASD may respond atypically to medications, the medications can have adverse side effects, and no known medication relieves autism's core symptoms of social and communication impairments.[60]

Many other therapies and interventions are available. Few are supported by scientific studies.[5][23][79][80] Treatment approaches lack empirical support in quality-of-life contexts, and many programs focus on success measures that lack predictive validity and real-world relevance.[24] Scientific evidence appears to matter less to service providers than program marketing, training availability, and parent requests.[81] Even if they do not help, conservative treatments such as changes in diet are probably harmless aside from their bother and cost.[45] Dubious invasive treatments are a much more serious matter: for example, in 2005, botched chelation therapy killed a 5-year-old autistic boy.[46]

Treatment is expensive;[82] indirect costs are more so. A U.S. study estimated the average additional lifetime cost due exclusively to autism to be $3.2 million in 2003 U.S. dollars for an autistic individual born in 2000, with about 10% medical care, 30% nonmedical care such as child care and education, and 60% the lost economic productivity of individuals and their parents.[83] A British study estimated an average lifetime cost of ₤2.4 million in 1997–1998 British pounds.[84] Legal rights to treatment are complex, vary with location and age, and require advocacy by caregivers.[80] Publicly supported programs are often inadequate or inappropriate for a given child, and unreimbursed out-of-pocket medical or therapy expenses are associated with likelihood of family financial problems.[85] After childhood, key treatment issues include residential care, job training and placement, sexuality, social skills, and estate planning.[80]

Prognosis

No cure is known for autism. Most children with autism lack social support, meaningful relationships, future employment opportunities or self-determination.[24] Although core difficulties remain, the severity of symptoms often becomes less marked in later childhood.[86] Few high-quality studies address long-term prognosis. Some adults show modest improvement in some symptoms, but some decline; no study has focused on autism after midlife.[87] Acquiring language before age 6, having IQ above 50, and having a marketable skill all predict better outcomes; independent living is unlikely with severe autism.[88] A 2004 British study of 68 adults who were diagnosed before 1980 as autistic children with IQ above 50 found that 12% achieved a high level of independence as adults, 10% had some friends and were generally in work but required some support, 19% had some independence but were generally living at home and needed considerable support and supervision in daily living, 46% needed specialist residential provision from facilities specializing in ASD with a high level of support and very limited autonomy, and 12% needed high-level hospital care.[6] Changes in diagnostic practice and increased availability of effective early intervention make it unclear whether these findings can be generalized to recently diagnosed children.[4]

Epidemiology

Estimates of the prevalence of autism vary widely depending on diagnostic criteria, age of children screened, and geographical location.[89] Most recent reviews tend to estimate a prevalence of 1–2 per 1,000 for autism and close to 6 per 1,000 for ASD;[4] PDD-NOS is the vast majority of ASD, Asperger's is about 0.3 per 1,000 and the atypical forms childhood disintegrative disorder and Rett syndrome are much rarer.[90] A 2006 study of nearly 57,000 British nine- and ten-year-olds reported a prevalence of 3.89 per 1,000 for autism and 11.61 per 1,000 for ASD; these higher figures could be associated with broadening diagnostic criteria.[91]

The risk of autism is associated with several prenatal and perinatal risk factors. A 2007 review of risk factors found associated parental characteristics that included advanced maternal age, advanced paternal age, and maternal place of birth outside Europe or North America, and also found associated obstetric conditions that included low birth weight and gestation duration, and hypoxia during childbirth.[92]

About 10–15% of autism cases have an identifiable Mendelian (single-gene) condition, chromosome abnormality, or other genetic syndrome,[37] and ASD is associated with several genetic disorders.[93] Autism is associated with mental retardation: a 2001 British study of 26 autistic children found about 30% with intelligence in the normal range (IQ above 70), 50% with mild to moderate retardation, and about 20% with severe to profound retardation (IQ below 35). For ASD other than autism the association is much weaker: the same study reported about 94% of 65 children with PDD-NOS or Asperger's had normal intelligence.[94] ASD is also associated with epilepsy, with variations in risk of epilepsy due to age, cognitive level, and type of language disorder.[95] Boys are at higher risk for autism than girls. The ASD sex ratio averages 4.3:1 and is greatly modified by cognitive impairment: it may be close to 2:1 with mental retardation and more than 5.5:1 without. Recent studies have found no association with socioeconomic status, and have reported inconsistent results about associations with race or ethnicity.[4] Phobias, depression and other psychopathological disorders have often been described along with ASD but this has not been assessed systematically.[96]

Autism's incidence, despite its advantages for assessing risk, is less useful in autism epidemiology, as the disorder starts long before it is diagnosed, and the gap between initiation and diagnosis is influenced by many factors unrelated to risk. Attention is focused mostly on whether prevalence is increasing with time. Earlier prevalence estimates were lower, centering at about 0.5 per 1,000 for autism during the 1960s and 1970s and about 1 per 1,000 in the 1980s, as opposed to today's 1–2 per 1,000.[4]

The number of reported cases of autism increased dramatically in the 1990s and early 2000s. This increase is largely attributable to changes in diagnostic practices, referral patterns, availability of services, age at diagnosis, and public awareness,[97] though as-yet-unidentified contributing environmental risk factors cannot be ruled out.[3] A widely cited 2002 pilot study concluded that the observed increase in autism in California cannot be explained by changes in diagnostic criteria,[98] but a 2006 analysis found that special education data poorly measured prevalence because so many cases were undiagnosed, and that the 1994–2003 U.S. increase was associated with declines in other diagnostic categories, indicating that diagnostic substitution had occurred.[99] It is unknown whether autism's prevalence increased during the same period. An increase in prevalence would suggest directing more attention and funding toward changing environmental factors instead of continuing to focus on genetics.[44]

History

A few examples of autistic symptoms and treatments were described long before autism was named. The Table Talk of Martin Luther contains a story of a 12-year-old boy who may have been severely autistic.[100] According to Luther's notetaker Mathesius, Luther thought the boy was a soulless mass of flesh possessed by the devil, and suggested that he be suffocated.[101] Victor of Aveyron, a feral child caught in 1798, showed several signs of autism; the medical student Jean Itard treated him with a behavioral program designed to help him form social attachments and to induce speech via imitation.[102]

The New Latin word autismus (English translation autism) was coined by the Swiss psychiatrist Eugen Bleuler in 1910 as he was defining symptoms of schizophrenia. He derived it from the Greek word autos (αὐτός, meaning self), and used it to mean morbid self-admiration, referring to "autistic withdrawal of the patient to his fantasies, against which any influence from outside becomes an intolerable disturbance."[103]

The word autism took its modern sense in 1943 when Leo Kanner of the Johns Hopkins Hospital reported 11 children with striking behavioral similarities and introduced the label early infantile autism.[28] He suggested autism to describe the children's lack of interest in other people. Almost all the characteristics described in Kanner's first paper on the subject, notably "autistic aloneness" and "insistence on sameness," are still regarded as typical of the autistic spectrum of disorders.[36] About the same time, the Viennese pediatrician Hans Asperger described a similar form of ASD now known as Asperger's, though for various reasons it was not widely recognized as a separate syndrome until 1981.[102]

Kanner's reuse of autism led to decades of confused terminology like "infantile schizophrenia," and child psychiatry's focus on maternal deprivation during the mid-1900s led to misconceptions of autism as an infant's response to "refrigerator mothers." Starting in the late 1960s autism was established as a separate syndrome by demonstrating that it is lifelong, distinguishing it from mental retardation and schizophrenia and from other developmental disorders, and demonstrating the benefits of involving parents in active programs of therapy.[104] Since then, the rise of parent organizations and the destigmatization of childhood ASD have deeply affected how we view ASD, its boundaries, and its treatments.[102] The Internet has helped autistic individuals bypass nonverbal cues and emotional sharing that they find so hard to deal with, and has given them a way to form online communities and work remotely.[105] Sociological and cultural aspects of autism have developed: some in the community seek a cure, while others believe that autism is simply another way of being.[7][106]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Freitag CM (2007). The genetics of autistic disorders and its clinical relevance: a review of the literature. Mol Psychiatry 12 (1): 2–22.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Arndt TL, Stodgell CJ, Rodier PM (2005). The teratology of autism. Int J Dev Neurosci 23 (2–3): 189–99.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Rutter M (2005). Incidence of autism spectrum disorders: changes over time and their meaning. Acta Paediatr 94 (1): 2–15.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Newschaffer CJ, Croen LA, Daniels J et al. (2007). The epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Annu Rev Public Health 28: 235–58.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Francis K (2005). Autism interventions: a critical update. Dev Med Child Neurol 47 (7): 493–99.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Howlin P, Goode S, Hutton J, Rutter M (2004). Adult outcome for children with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 45 (2): 212–29.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Rajendran G, Mitchell P (2007). Cognitive theories of autism. Dev Rev 27 (2): 224–60.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 World Health Organization (2006). "F84. Pervasive developmental disorders", International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, 10th ed. (ICD-10). Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 Penn HE (2006). Neurobiological correlates of autism: a review of recent research. Child Neuropsychol 12 (1): 57–79.

- ↑ Lord C, Cook EH, Leventhal BL, Amaral DG (2000). Autism spectrum disorders. Neuron 28 (2): 355–63.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2000). "Diagnostic criteria for 299.80 Asperger's Disorder (AD)", Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., text revision (DSM-IV-TR). ISBN 0890420254. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

- ↑ Piven J, Palmer P, Jacobi D, Childress D, Arndt S (1997). Broader autism phenotype: evidence from a family history study of multiple-incidence autism families. Am J Psychiatry 154 (2): 185–90.

- ↑ Happé F (1999). Understanding assets and deficits in autism: why success is more interesting than failure. Psychologist 12 (11): 540–47.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Baron-Cohen S (2006). The hyper-systemizing, assortative mating theory of autism. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 30 (5): 865–72.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Cohen D, Pichard N, Tordjman S et al. (2005). Specific genetic disorders and autism: clinical contribution towards their identification. J Autism Dev Disord 35 (1): 103–16.

- ↑ Autism and Asperger's:

- Schopler E, Mesibov GB, Kunce LJ (eds) (1998). Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism?. Springer. ISBN 0306457466.

- Klin A (2006). Autism and Asperger syndrome: an overview. Rev Bras Psiquiatr 28 (Suppl 1): S3–S11.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Landa R (2007). Early communication development and intervention for children with autism. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 13 (1): 16–25.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 Volkmar F, Chawarska K, Klin A (2005). Autism in infancy and early childhood. Annu Rev Psychol 56: 315–36.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Filipek PA, Accardo PJ, Baranek GT et al. (1999). The screening and diagnosis of autistic spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 29 (6): 439–84. Erratum (2000). J Autism Dev Disord 30 (1): 81. Digital object identifier (DOI): 10.1023/A:1017256313409 . PMID 10638459. This paper represents a consensus of representatives from nine professional and four parent organizations in the U.S.

- ↑ Sacks O (1995). An Anthropologist on Mars: Seven Paradoxical Tales. Knopf. ISBN 0679437851.

- ↑ Sigman M, Dijamco A, Gratier M, Rozga A (2004). Early detection of core deficits in autism. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 10 (4): 221–33.

- ↑ Rutgers AH, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, van IJzendoorn MH, van Berckelaer-Onnes IA (2004). Autism and attachment: a meta-analytic review. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 45 (6): 1123–34.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Sigman M, Spence SJ, Wang AT (2006). Autism from developmental and neuropsychological perspectives. Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2: 327–55.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Burgess AF, Gutstein SE (2007). Quality of life for people with autism: raising the standard for evaluating successful outcomes. Child Adolesc Ment Health 12 (2): 80–86.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 Dominick KC, Davis NO, Lainhart J, Tager-Flusberg H, Folstein S (2007). Atypical behaviors in children with autism and children with a history of language impairment. Res Dev Disabil 28 (2): 145–62.

- ↑ Noens I, van Berckelaer-Onnes I, Verpoorten R, van Duijn G (2006). The ComFor: an instrument for the indication of augmentative communication in people with autism and intellectual disability. J Intellect Disabil Res 50 (9): 621–32.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Tager-Flusberg H, Caronna E (2007). Language disorders: autism and other pervasive developmental disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am 54 (3): 469–81.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Kanner L (1943). Autistic disturbances of affective contact. Nerv Child 2: 217–50.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Williams DL, Goldstein G, Minshew NJ (2006). Neuropsychologic functioning in children with autism: further evidence for disordered complex information-processing. Child neuropsychol 12 (4–5): 279–98.

- ↑ Bodfish JW, Symons FJ, Parker DE, Lewis MH (2000). Varieties of repetitive behavior in autism: comparisons to mental retardation. J Autism Dev Disord 30 (3): 237–43.

- ↑ Treffert DA (2007). Savant syndrome: an extraordinary condition. Wisconsin Medical Society. Retrieved 2007-07-13.

- ↑ Rogers SJ, Ozonoff S (2005). Annotation: what do we know about sensory dysfunction in autism? A critical review of the empirical evidence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 46 (12): 1255–68.

- ↑ Ming X, Brimacombe M, Wagner GC (2007). Prevalence of motor impairment in autism spectrum disorders. Brain Dev.

- ↑ Erickson CA, Stigler KA, Corkins MR, Posey DJ, Fitzgerald JF, McDougle CJ (2005). Gastrointestinal factors in autistic disorder: a critical review. J Autism Dev Disord 35 (6): 713–27.

- ↑ Trottier G, Srivastava L, Walker CD (1999). Etiology of infantile autism: a review of recent advances in genetic and neurobiological research. J Psychiatry Neurosci 24 (2): 103–15.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Happé F, Ronald A, Plomin R (2006). Time to give up on a single explanation for autism. Nat Neurosci 9 (10): 1218–20.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Folstein SE, Rosen-Sheidley B (2001). Genetics of autism: complex aetiology for a heterogeneous disorder. Nat Rev Genet 2 (12): 943–55.

- ↑ Bolton P, Macdonald H, Pickles A et al. (1994). A case-control family history study of autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 35 (5): 877–900.

- ↑ Persico AM, Bourgeron T (2006). Searching for ways out of the autism maze: genetic, epigenetic and environmental clues. Trends Neurosci 29 (7): 349–58.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Müller RA (2007). The study of autism as a distributed disorder. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 13 (1): 85–95.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 Beaudet AL (2007). Autism: highly heritable but not inherited. Nat Med 13 (5): 534–36.

- ↑ Sebat J, Lakshmi B, Malhotra D et al. (2007). Strong association of de novo copy number mutations with autism. Science 316 (5823): 445–49.

- ↑ Autism Genome Project Consortium (2007). Mapping autism risk loci using genetic linkage and chromosomal rearrangements. Nat Genet 39 (3): 319–28.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Szpir M (2006). Tracing the origins of autism: a spectrum of new studies. Environ Health Perspect 114 (7): A412–18.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 Christison GW, Ivany K (2006). Elimination diets in autism spectrum disorders: any wheat amidst the chaff?. J Dev Behav Pediatr 27 (2 Suppl 2): S162–71.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Doja A, Roberts W (2006). Immunizations and autism: a review of the literature. Can J Neurol Sci 33 (4): 341–46.

- ↑ DiCicco-Bloom E, Lord C, Zwaigenbaum L et al. (2006). The developmental neurobiology of autism spectrum disorder. J Neurosci 26 (26): 6897–6906.

- ↑ Ashwood P, Wills S, Van de Water J (2006). The immune response in autism: a new frontier for autism research. J Leukoc Biol 80 (1): 1–15.

- ↑ Krause I, He XS, Gershwin ME, Shoenfeld Y (2002). Brief report: immune factors in autism: a critical review. J Autism Dev Disord 32 (4): 337–45.

- ↑ MNS and autism:

- Ramachandran VS, Oberman LM (2006). Broken mirrors: a theory of autism. Sci Am 295 (5): 62–69.

- Williams JHG, Whiten A, Suddendorf T, Perrett DI (2001). Imitation, mirror neurons and autism. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 25 (4): 287–95.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Iacoboni M, Dapretto M (2006). The mirror neuron system and the consequences of its dysfunction. Nat Rev Neurosci 7 (12): 942–51.

- ↑ Just MA, Cherkassky VL, Keller TA, Minshew NJ (2004). Cortical activation and synchronization during sentence comprehension in high-functioning autism: evidence of underconnectivity. Brain 127 (8): 1811–21.

- ↑ Murias M, Webb SJ, Greenson J, Dawson G (2007). Resting state cortical connectivity reflected in EEG coherence in individuals with autism. Biol Psychiatry 62 (3): 270–73.

- ↑ Minshew NJ, Williams DL (2007). The new neurobiology of autism: cortex, connectivity, and neuronal organization. Arch Neurol 64 (7): 945–50.

- ↑ Baron-Cohen S (2002). The extreme male brain theory of autism. Trends Cogn Sci 6 (6): 248–54.

- ↑ Baron-Cohen S, Leslie AM, Frith U (1985). Does the autistic child have a 'theory of mind'?. Cognition 21 (1): 37–46.

- ↑ Hill EL (2004). Executive dysfunction in autism. Trends Cogn Sci 8 (1): 26–32.

- ↑ Happé F, Frith U (2006). The weak coherence account: detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 36 (1): 5–25.

- ↑ Mottron L, Dawson M, Soulières I, Hubert B, Burack J (2006). Enhanced perceptual functioning in autism: an update, and eight principles of autistic perception. J Autism Dev Disord 36 (1): 27–43.

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Strock, M (2007). "Autism spectrum disorders (pervasive developmental disorders)". NIH-04-5511. National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- ↑ Council on Children With Disabilities, Section on Developmental Behavioral Pediatrics, Bright Futures Steering Committee, Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee (2006). Identifying infants and young children with developmental disorders in the medical home: an algorithm for developmental surveillance and screening. Pediatrics 118 (1): 405–20. [Same authors] (2006). Errata. Pediatrics 118 (4): 1808–09.

- ↑ Williams J, Brayne C (2006). Screening for autism spectrum disorders: what is the evidence?. Autism 10 (1): 11–35.

- ↑ McMahon WM, Baty BJ, Botkin J (2006). Genetic counseling and ethical issues for autism. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet 142C (1): 52–57.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2000). "Diagnostic criteria for 299.00 Autistic Disorder", Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th ed., text revision (DSM-IV-TR). ISBN 0890420254. Retrieved 2007-06-25.

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Dover CJ, Le Couteur A (2007). How to diagnose autism. Arch Dis Child 92 (6): 540–45.

- ↑ Mantovani JF (2000). Autistic regression and Landau-Kleffner syndrome: progress or confusion?. Dev Med Child Neurol 42 (5): 349–53.

- ↑ Landa RJ, Holman KC, Garrett-Mayer E (2007). Social and communication development in toddlers with early and later diagnosis of autism spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry 64 (7): 853–64.

- ↑ Wiggins LD, Baio J, Rice C (2006). Examination of the time between first evaluation and first autism spectrum diagnosis in a population-based sample. J Dev Behav Pediatr 27 (2 Suppl): S79–87.

- ↑ Shattuck PT, Grosse SD (2007). Issues related to the diagnosis and treatment of autism spectrum disorders. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 13 (2): 129–35.

- ↑ Cass H (1998). Visual impairment and autism: current questions and future research. Autism 2 (2): 117–38.

- ↑ Why get a diagnosis as an adult?. The National Autistic Society (2005). Retrieved 2007-06-29.

- ↑ Bryson SE, Rogers SJ, Fombonne E (2003). Autism spectrum disorders: early detection, intervention, education, and psychopharmacological management. Can J Psychiatry 48 (8): 506–16.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services (1999). "Autism", Mental Health: A Report of the Surgeon General. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Mental Health Services, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved on 2007-07-11.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 Howard JS, Sparkman CR, Cohen HG, Green G, Stanislaw H (2005). A comparison of intensive behavior analytic and eclectic treatments for young children with autism. Res Dev Disabil 26 (4): 359–83.

- ↑ Van Bourgondien ME, Reichle NC, Schopler E (2003). Effects of a model treatment approach on adults with autism. J Autism Dev Disord 33 (2): 131–40.

- ↑ Oswald DP, Sonenklar NA (2007). Medication use among children with autism spectrum disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol 17 (3): 348–55.

- ↑ FDA (2006-10-06). FDA approves the first drug to treat irritability associated with autism, Risperdal. Press release. Retrieved on 2007-08-08.

- ↑ Broadstock M, Doughty C, Eggleston M (2007). Systematic review of the effectiveness of pharmacological treatments for adolescents and adults with autism spectrum disorder. Autism 11 (4): 335–48.

- ↑ Lack of support for interventions:

- Herbert JD, Sharp IR, Gaudiano BA (2002). Separating fact from fiction in the etiology and treatment of autism: a scientific review of the evidence. Sci Rev Ment Health Pract 1 (1): 23–43.

- Howlin P (2005). "The effectiveness of interventions for children with autism", in Fleischhacker WW, Brooks DJ: Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Springer, 101–119. DOI:10.1007/3-211-31222-6_6. ISBN 3211262911. PMID 16355605.

- Rao PA, Beidel DC, Murray MJ (2007). Social skills interventions for children with Asperger's syndrome or high-functioning autism: a review and recommendations. J Autism Dev Disord.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 Aman MG (2005). Treatment planning for patients with autism spectrum disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 66 (Suppl 10): 38–45.

- ↑ Stahmer AC, Collings NM, Palinkas LA (2005). Early intervention practices for children with autism: descriptions from community providers. Focus Autism Other Dev Disabl 20 (2): 66–79.

- ↑ Shimabukuro TT, Grosse SD, Rice C (2007). Medical expenditures for children with an autism spectrum disorder in a privately insured population. J Autism Dev Disord.

- ↑ Ganz ML (2007). The lifetime distribution of the incremental societal costs of autism. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161 (4): 343–49.

- ↑ Järbrink K, Knapp M (2001). The economic impact of autism in Britain. Autism 5 (1): 7–22.

- ↑ Sharpe DL, Baker DL (2007). Financial issues associated with having a child with autism. J Fam Econ Iss 28 (2): 247–64.

- ↑ Howlin P (2006). Autism spectrum disorders. Psychiatry 5 (9): 320–24.

- ↑ Seltzer MM, Shattuck P, Abbeduto L, Greenberg JS (2004). Trajectory of development in adolescents and adults with autism. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 10 (4): 234–47.

- ↑ Tidmarsh L, Volkmar FR (2003). Diagnosis and epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Can J Psychiatry 48 (8): 517–25.

- ↑ Williams JG, Higgins JPT, Brayne CEG (2006). Systematic review of prevalence studies of autism spectrum disorders. Arch Dis Child 91 (1): 8–15.

- ↑ Fombonne E (2005). Epidemiology of autistic disorder and other pervasive developmental disorders. J Clin Psychiatry 66 (Suppl 10): 3–8.

- ↑ Baird G, Simonoff E, Pickles A et al. (2006). Prevalence of disorders of the autism spectrum in a population cohort of children in South Thames: the Special Needs and Autism Project (SNAP). Lancet 368 (9531): 210–15.

- ↑ Kolevzon A, Gross R, Reichenberg A (2007). Prenatal and perinatal risk factors for autism. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 161 (4): 326–33.

- ↑ Zafeiriou DI, Ververi A, Vargiami E (2007). Childhood autism and associated comorbidities. Brain Dev 29 (5): 257–72.

- ↑ Chakrabarti S, Fombonne E (2001). Pervasive developmental disorders in preschool children. JAMA 285 (24): 3093–99.

- ↑ Tuchman R, Rapin I (2002). Epilepsy in autism. Lancet Neurol 1 (6): 352–58.

- ↑ Matson JL, Nebel-Schwalm MS (2007). Comorbid psychopathology with autism spectrum disorder in children: an overview. Res Dev Disabil 28 (4): 341–52.

- ↑ Changes in diagnostic practices:

- Fombonne E (2003). The prevalence of autism. JAMA 289 (1): 87–89.

- Wing L, Potter D (2002). The epidemiology of autistic spectrum disorders: is the prevalence rising?. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev 8 (3): 151–61.

- ↑ Byrd RS, Sage AC, Keyzer J et al. (2002). "Report to the legislature on the principal findings of the epidemiology of autism in California: a comprehensive pilot study". M.I.N.D. Institute. Retrieved 2006-09-18.

- ↑ Shattuck PT (2006). The contribution of diagnostic substitution to the growing administrative prevalence of autism in US special education. Pediatrics 117 (4): 1028–37.

- ↑ Wing L (1997). The history of ideas on autism: legends, myths and reality. Autism 1 (1): 13–23.

- ↑ Miles M (2005). Martin Luther and childhood disability in 16th century Germany: what did he write? what did he say?. Independent Living Institute. Retrieved 2007-07-18.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 102.2 Wolff S (2004). The history of autism. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 13 (4): 201–08.

- ↑ Kuhn R; tr. Cahn CH (2004). Eugen Bleuler's concepts of psychopathology. Hist Psychiatry 15 (3): 361–66. The quote is a translation of Bleuler's 1910 original.

- ↑ Fombonne E (2003). Modern views of autism. Can J Psychiatry 48 (8): 503–05.

- ↑ Biever C. "Web removes social barriers for those with autism", New Scientist, 2007-06-27. Retrieved 2007-06-28.

- ↑ Gal L. "Who says autism's a disease?", Haaretz, 2007-06-28. Retrieved 2007-07-16.

External links

- {{{2}}} at the Open Directory Project

- Autism-help.org

- National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities (NICHCY), autism resources

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.