Difference between revisions of "Apostasy" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 15: | Line 15: | ||

In the [[Hebrew Bible]] apostasy is equated with rebellion against God, His Law, and the loss of faith of the Israelites. The penalty for apostasy in Deuteronomy 13:1-10 is death | In the [[Hebrew Bible]] apostasy is equated with rebellion against God, His Law, and the loss of faith of the Israelites. The penalty for apostasy in Deuteronomy 13:1-10 is death | ||

| − | <blockquote> | + | <blockquote>That [[prophet]] or that dreamer (who leads you to worship of other gods) shall be put to death, because... he has preached apostasy from [[Yahweh|The Lord]] your God... If your own full brother, or your son or daughter, or your beloved wife, or your intimate friend, entices you secretly to serve other gods... do not yield to him or listen to him, nor look with pity upon him, to spare or shield him, but kill him... You shall stone him to death, because he sought to lead you astray from the Lord, your God. </blockquote> |

| − | + | [[Image:Finding-law.jpg|thumb|250px|Priests "find" the Book of the Law, believed by many to be [[Deuteronomy]], the [[Temple of Jerusalem]] (1 Kings 22).]] | |

| − | + | However, there are few instances when this harsh attitude seems to have been enforced. Indeed, the constant reminders of the prophets and biblical writers warning against [[idolatry]] demonstrate that [[Deuteronomy]]'s standard was hardly the "law of the land" in today's sense. Indeed, modern scholars believe the Book of Deuternomy not to have originated in the time of Moses, as is traditionally believed, but in the time of King Josiah in the late seventh century B.C.E.. | |

| − | There are several | + | There are several examples, however, where strict punishment was indeed given to those who caused the [[Israelites]] to violate their faith in [[Yahweh]] alone. When the Hebrews were about to enter [[Canaan]], many Israelite men were reportedly led to worship [[Baal]]-Peor by [[Moabite]] and [[Midianite]] women. One of these men was slain together with his Midianite wife by the priest Phinehas (Numbers 25). The Midianite crime was considered so serious that Moses then launched a war of extermination against them. |

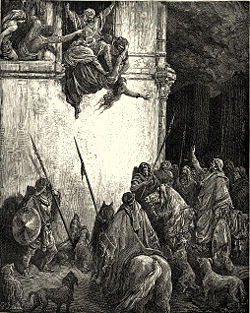

| − | + | [[Image:The Death of Jezebel.jpg|thumb|250px|left|''The Death of Jezebel'' by [[Gustave Doré]].]] | |

| − | + | Perhaps the most remembered story of Israelite apostasy is that brought on by [[Jezebel]], the wife of King [[Ahab]]. Jezebel herself was not an Israelite, but was originally a princess of the coastal [[Phoenicia]]n city of Tyre, in modern day [[Lebanon]]. When Jezebel married Ahab (ruled c. 874–853 B.C.E.), she persuaded him to introduce [[Ba'al]] worship. The prophets [[Elijah]] and [[Eilisha]] condemned this practice as a sign of being unfaithful to Yahweh. | |

| − | However, by the time of the prophet Jeremiah, the worship of Canaanite gods continued unabated, as he complained: | + | Elijah ordered 450 prophets of Baal slain after they had lost a famous contest with him on [[Mount Carmel]]. Elijah's successor, [[Elisha]], cause the military commander [[Jehu]] to be anointed as king of Israel while Ahab's son [[Jehoram]] was still on the throne. Jehu himself [[Jehoram]] and then went to Jezebel's palace and ordered her slain as well. |

| + | |||

| + | The Bible speaks of many other notable defections from the Jewish faith: e.g., Isaiah 1:2-4 or Jeremiah 2:19, as do the writings of the prophet Ezekiel (e.g., Ezekiel 16 or 18). Israelite kings were often judged guilty of apostasy. Examples include Ahab (I Kings 16:30-33), Ahaziah (I Kings 22:51-53), Jehoram (2 Chronicles 21:6,10), Ahaz (2 Chronicles 28:1-4), Amon (2 Chronicles 33:21-23), and others. | ||

| + | |||

| + | However, by the time of the prophet Jeremiah in the early sixth century B.C.E., the worship of [[Canaanite]] gods continued unabated, as he complained: | ||

<blockquote>Do you not see what they are doing in the towns of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem? The children gather wood, the fathers light the fire, and the women knead the dough and make cakes of bread for the Queen of Heaven. They pour out drink offerings to other gods to provoke me to anger (Jeremiah 7:17-18)</blockquote> | <blockquote>Do you not see what they are doing in the towns of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem? The children gather wood, the fathers light the fire, and the women knead the dough and make cakes of bread for the Queen of Heaven. They pour out drink offerings to other gods to provoke me to anger (Jeremiah 7:17-18)</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | After the [[Babylonian Exile]], the Deuteronimc code seems to have been taken more seriously, but examples of its enforcement are scanty at best. Periods of increased apostasy were evident, however. The most well known of these came during the administration of the Seleucid Greek ruler [[Aniochus IV]] Epiphanes in the second century CE, who virtually banned Jewish worship until the [[Macabeean revolt]] established an indepent Jewish dynasty. | ||

At the beginning of the Common Era, Judaism face a new threat of apostasy from the new religion of Christianity. At first, believers in Jesus were treated as a group within Judaism (see Acts 21), but was later considered heretical, and finally—as Christians began proclaiming the end of the Abrahamic covenant, the divinity of Christ, the docrtine of the Trinity—those Jews who converted to belief in Jesus were treated as apsotates. The situation was compounded by Christians themselves treating Jews with contempt. In the Christian Roman Empire, Constantine I forbade Christians to fellowship with Jews, preachers such as Saint John Chysostom preached firey sermons against Judaism, and Christian mobs sometimes destroyed Jewish synagogue at the urging of local bishops. | At the beginning of the Common Era, Judaism face a new threat of apostasy from the new religion of Christianity. At first, believers in Jesus were treated as a group within Judaism (see Acts 21), but was later considered heretical, and finally—as Christians began proclaiming the end of the Abrahamic covenant, the divinity of Christ, the docrtine of the Trinity—those Jews who converted to belief in Jesus were treated as apsotates. The situation was compounded by Christians themselves treating Jews with contempt. In the Christian Roman Empire, Constantine I forbade Christians to fellowship with Jews, preachers such as Saint John Chysostom preached firey sermons against Judaism, and Christian mobs sometimes destroyed Jewish synagogue at the urging of local bishops. | ||

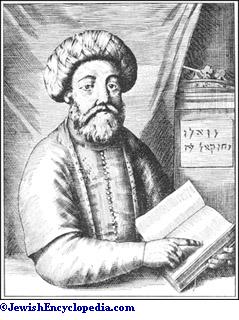

| − | During the Spanish | + | [[Image:Shabbatai1.jpg|thumb|Shabbatai Sevi, thought be many Jews to be the Messiah, until he apostasized to Islam.]] |

| + | |||

| + | During the [[Spanish Inquisition]], apostasy took on a new meaning. Forcing Jews to renounce their religion under threat of expulsion or even death complicated the issue of what qualified as "apostasy" in Judaism. Many rabbis generally considered the behavior of a Jew, rather than his professed public belief, to be the determining factor. Thus, large numbers of Jews became [[Marranos]], publicly acting as Christian, but privately acting as Jews as best they could. On the other hand some well-known Jews converted to Christianity with enthusiasm and even engaged in public debates encouraging their fellow Jews to apostasize. | ||

| − | A partiularly well known case of apostasy was that of the [[ | + | A partiularly well known case of apostasy was that of the [[Shabbatai Sevi]] in 1566. Shabbatai was a famous mystic and kabbalist, who was accepted by a large proporation of Jews as the [[Messiah]] until he apostasized to Islam. |

It should also be noted that from the time of early Talmudic sages in the second century CE, the rabbis took the attitude than Jews could hold to a variety of theological attitudes and still be considered a Jew. In modern times, this attitude was exemplified by Abraham Isaac Kook (1864-1935), the first Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community in the British Mandate for [[Palestine]], who held that even Jewish [[atheist]]s were not apostate. Kook held that, in practice, atheists were actually helping true religion to burn away false images of God, thus in the end serving the purpose of true [[monotheism]]. | It should also be noted that from the time of early Talmudic sages in the second century CE, the rabbis took the attitude than Jews could hold to a variety of theological attitudes and still be considered a Jew. In modern times, this attitude was exemplified by Abraham Isaac Kook (1864-1935), the first Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community in the British Mandate for [[Palestine]], who held that even Jewish [[atheist]]s were not apostate. Kook held that, in practice, atheists were actually helping true religion to burn away false images of God, thus in the end serving the purpose of true [[monotheism]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Sanctions against apostasy in Judaism today include the Othodox tradition of shunning a person who leaves the faith, in which the parents formally mourn their lost child and treat him or her as dead. Apostates in the [[State of Israel]] are forbidden to marry other Jews. | ||

===In Christianity=== | ===In Christianity=== | ||

| + | Apostasy in [[Christianity]] began early in its history. [[Saint Paul]] started out his career attempting to influence Christians to apostasize from the new faith (Acts 8) and revert to othodox Judaism. Ironically, when Christianity separated itself from [[Judaism]], Jewish Christians who kept to the Mosaic traditions were considered either heretics or apostates. | ||

| − | + | In Christian tradition, apostates were to be shunned by other members of the church. Titus 3:10 indicates that an apostate or heretic needs to be "rejected after the first and second admonition." Hebrews 6:4-6 afirms the impossibility of those who have fallen away "to be brought back to repentance." | |

| − | + | Many of the early [[martyr]]s died for their faith rather than apostasizing, but others gave in to the persecutors and offered sacrifice to the Roman gods. It is difficult to know how many quietly returned to pagan belief or to Judaism during the first centuries of Christian history. | |

| − | + | [[Image:JulianusII-antioch(360-363)-CNG.jpg|thumb|left|Julian the Apostate]] | |

| − | + | With the conversion of [[Constantine I]] and the later establishment of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman state, the situation changed dramatically. Rather than being punished by the state if one refused to apostasize, a person would be sanctioned for apostasy, which became a civil offense punishable by law. This changed briefly under the administration of Emperior Julianus II (331-363 C.E.)—known to history as [[Julian the Apostate]] for his policy of divorcing the Roman state from its recent union with the Christian Church. | |

| − | + | For more than a millennium afte Julian's death Christian states used the power of the sword to protect the Church against apostasy and [[heresy]]. Apostates were deprived of their civil as well as their religious rights. Torture was freely employed to extract confessions and to encourage recantations. Apostates and schismatics were not only excommunicated from the Church but persecuted by the state. | |

| − | + | Apostasy on a grand scale took place several times. The “[[Great Schism]]” between Eastern Orthodoxy and Western Catholicism in the eighth century resulted in mutual excommunication. The [[Protestant Reformation]] in the sixteenth century further divided Christian against Christian. Each sectarian group claimed to have recovered the authentic faith and practice of the [[New Testament]] Church, thereby relegating rival versions of Christianity to the status of apostasy. | |

| − | + | After decades of warfare in Europe, Christian tradition gradually came to accept the principle of tolerance and [[religioius freedom]]. Today, no major Christian denomination calls for legal sanctions against those who apostasize, although some denominations do excommunicate those who turn to other faiths, and some groups still practice [[shunning]]. | |

===In Islam=== | ===In Islam=== | ||

Islam imposes harsh penalties for apostasy. The [[Qur'an]] has many passages that are critical of apostasy, but is silent on the proper punishment. In the [[Hadith]], on the other hand, the death penalty is very explicit. | Islam imposes harsh penalties for apostasy. The [[Qur'an]] has many passages that are critical of apostasy, but is silent on the proper punishment. In the [[Hadith]], on the other hand, the death penalty is very explicit. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Salman Rushdie.jpg|thumb|Author [[Salman Rushdie]] is considered an apostate from Islam was given a death sentence by several Islamic authorities.]] | ||

Today apostasy is punishable by death in [[Saudi Arabia]], [[Yemen]], [[Iran]], [[Sudan]], [[Afghanistan]], [[Mauritania]], and the [[Comoros]]. In Qatar apostasy is a also capital offense, but no executions have been reported for it. Most other Muslim states punish apostasy by both whipping and imprisonment. | Today apostasy is punishable by death in [[Saudi Arabia]], [[Yemen]], [[Iran]], [[Sudan]], [[Afghanistan]], [[Mauritania]], and the [[Comoros]]. In Qatar apostasy is a also capital offense, but no executions have been reported for it. Most other Muslim states punish apostasy by both whipping and imprisonment. | ||

| Line 83: | Line 96: | ||

===New Religious Movements=== | ===New Religious Movements=== | ||

| − | As with Christianity in its early days, [[New Religious Movement]]s (NRMs) face the problem of apostasy | + | As with Christianity in its early days, [[New Religious Movement]]s (NRMs) face the problem of apostasy among their converts due to pressure from family, society, and members simply turning against their newfound faith. |

| − | + | A number of members of NRM members also apostasize under the pressure of [[deprogramming]], in which they are kindapped by members of their families and forcibly confined in order to influence them to leave the group. Part of the "rehabilitation" process in deprogramming often involves requiring a person to publicly criticize his or her former religion—a true act of apostasy. In some cases, members of NRM "fake" apostasy in order to escape from forcible confinement and later return to their groups, but in other cases, the apostasy is real. | |

| − | + | Some apostasy from New Religious Movements takes place through a process known as "exit counseling," which involves no kidnapping or forcible confinement. In other cases, NRM members decide to apostasize without any intense effort to inflence their leaving the group. | |

| − | + | Apostates of NRMs may make a number of allegations against their former group and its leaders. This list includes one or more of the following: unkept promises, [[sexual abuse]] by the leader, irrational and contradictory teachings, deception, financial exploitation, demonizing of the outside world, abuse of power, [[hypocrisy]] of the leadership, unnecessary secrecy, discouragement of [[critical thinking]], [[brainwashing]], [[mind control]], [[pedophilia]], and a leadership that does not admit any mistakes. | |

| − | While some of these allegations are based in fact, others are exaggerations and outright falsehoods. The roles that apostates play in opposition to | + | While some of these allegations are based in fact, others are exaggerations and outright falsehoods. The roles that apostates play in opposition to NRMs are controversial subjects of debate among scholars of religion, sociologists and psychologists. One noted study proposes that stories of apostates are likely to paint a caricature of the group, shaped by the apostate's current role rather than his objective experience in the group. <ref>in Bromley, David G et al. (ed.), ''Brainwashing Deprogramming Controversy: Sociological, Psychological, Legal, and Historical Perspectives (Studies in religion and society)'' p. 156, 1984, ISBN 0-88946-868-0</ref> |

Sociologist [[Lewis A. Coser]] holds an apostate to be not just a person who experienced a dramatic change in conviction but one who, "is spiritually living... in the struggle against the old faith and for the sake of its negation.''"<ref>Lewis A. Coser ''The Age of the Informer'' Dissent:1249-54, 1954</ref> | Sociologist [[Lewis A. Coser]] holds an apostate to be not just a person who experienced a dramatic change in conviction but one who, "is spiritually living... in the struggle against the old faith and for the sake of its negation.''"<ref>Lewis A. Coser ''The Age of the Informer'' Dissent:1249-54, 1954</ref> | ||

[[David Bromley]] defined the apostate role as follows and distinguished it from the ''[[defection|defector]]'' and ''[[whistleblower]]'' roles.<ref name="bromley1998">Bromley, David G. (Ed.) ''The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements'' CT, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7</ref> | [[David Bromley]] defined the apostate role as follows and distinguished it from the ''[[defection|defector]]'' and ''[[whistleblower]]'' roles.<ref name="bromley1998">Bromley, David G. (Ed.) ''The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements'' CT, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7</ref> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Stuart A. Wright | + | Stuart A. Wright asserts that apostasy is a unique phenomenon and a distinct type of religious defection, in which the apostate is a defector "who is aligned with an oppositional coalition in an effort to broaden the dispute, and embraces public claimsmaking activities to attack his or her former group." <ref> Wright, Stuart, A., '' Exploring Factors that Shatpe the Apostate Role'', in Bromley, David G., ''The Politics of Religious Apostasy'', pp. 109, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7</ref> |

==In International law== | ==In International law== | ||

| + | [[Image:EleanorRooseveltHumanRights.gif|thumb|250px|Eleanor Roosevelt holds a copy of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.]] | ||

The United Nations, in its Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 18, affirmed the right of a person to change his religion, and thus to apostasize: | The United Nations, in its Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 18, affirmed the right of a person to change his religion, and thus to apostasize: | ||

Revision as of 02:58, 30 August 2007

Apostasy is the formal renunciation of one's religion. One who commits apostasy is called an apostate. Many religious faiths consider apostasy to be a serious sin. In some religious faiths an apostate can be excommunicated. In some Middle Eastern countries, apostasy is punishable by death. Apostates are often shunned by the members of their former religious group.

When used by sociologists apostasy refers to the renunciation and/or criticism of, or opposition to one's former religion. Few former believers would call themselves "apostates" because this phrase is generally used in a perjorative sense. Sociologists also make a distinction between apostasy and "defection" or "leave-taking," neither of which involves public opposition to one's former religion.

The difference between apostasy and heresy is that the latter refers to the corruption of specific religious doctrines but is not a complete abandonment of one's religious faith. Some atheists and agnostics use the term "deconversion" instead of "apostasy" to describe the loss of faith in a religion.

Asostasy, as an act of religious conscience, has acquired a protected legal status in international law by the United Nations, which affirms the right to change one's religion or belief under Article 18 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Apostasy is also used to refer to the renunciation of belief in a cause other than a particular religous faith, particularly in the area of politics.

Apostasy in the Arahamic religions

Judaism

In the Hebrew Bible apostasy is equated with rebellion against God, His Law, and the loss of faith of the Israelites. The penalty for apostasy in Deuteronomy 13:1-10 is death

That prophet or that dreamer (who leads you to worship of other gods) shall be put to death, because... he has preached apostasy from The Lord your God... If your own full brother, or your son or daughter, or your beloved wife, or your intimate friend, entices you secretly to serve other gods... do not yield to him or listen to him, nor look with pity upon him, to spare or shield him, but kill him... You shall stone him to death, because he sought to lead you astray from the Lord, your God.

However, there are few instances when this harsh attitude seems to have been enforced. Indeed, the constant reminders of the prophets and biblical writers warning against idolatry demonstrate that Deuteronomy's standard was hardly the "law of the land" in today's sense. Indeed, modern scholars believe the Book of Deuternomy not to have originated in the time of Moses, as is traditionally believed, but in the time of King Josiah in the late seventh century B.C.E.

There are several examples, however, where strict punishment was indeed given to those who caused the Israelites to violate their faith in Yahweh alone. When the Hebrews were about to enter Canaan, many Israelite men were reportedly led to worship Baal-Peor by Moabite and Midianite women. One of these men was slain together with his Midianite wife by the priest Phinehas (Numbers 25). The Midianite crime was considered so serious that Moses then launched a war of extermination against them.

Perhaps the most remembered story of Israelite apostasy is that brought on by Jezebel, the wife of King Ahab. Jezebel herself was not an Israelite, but was originally a princess of the coastal Phoenician city of Tyre, in modern day Lebanon. When Jezebel married Ahab (ruled c. 874–853 B.C.E.), she persuaded him to introduce Ba'al worship. The prophets Elijah and Eilisha condemned this practice as a sign of being unfaithful to Yahweh.

Elijah ordered 450 prophets of Baal slain after they had lost a famous contest with him on Mount Carmel. Elijah's successor, Elisha, cause the military commander Jehu to be anointed as king of Israel while Ahab's son Jehoram was still on the throne. Jehu himself Jehoram and then went to Jezebel's palace and ordered her slain as well.

The Bible speaks of many other notable defections from the Jewish faith: e.g., Isaiah 1:2-4 or Jeremiah 2:19, as do the writings of the prophet Ezekiel (e.g., Ezekiel 16 or 18). Israelite kings were often judged guilty of apostasy. Examples include Ahab (I Kings 16:30-33), Ahaziah (I Kings 22:51-53), Jehoram (2 Chronicles 21:6,10), Ahaz (2 Chronicles 28:1-4), Amon (2 Chronicles 33:21-23), and others.

However, by the time of the prophet Jeremiah in the early sixth century B.C.E., the worship of Canaanite gods continued unabated, as he complained:

Do you not see what they are doing in the towns of Judah and in the streets of Jerusalem? The children gather wood, the fathers light the fire, and the women knead the dough and make cakes of bread for the Queen of Heaven. They pour out drink offerings to other gods to provoke me to anger (Jeremiah 7:17-18)

After the Babylonian Exile, the Deuteronimc code seems to have been taken more seriously, but examples of its enforcement are scanty at best. Periods of increased apostasy were evident, however. The most well known of these came during the administration of the Seleucid Greek ruler Aniochus IV Epiphanes in the second century CE, who virtually banned Jewish worship until the Macabeean revolt established an indepent Jewish dynasty.

At the beginning of the Common Era, Judaism face a new threat of apostasy from the new religion of Christianity. At first, believers in Jesus were treated as a group within Judaism (see Acts 21), but was later considered heretical, and finally—as Christians began proclaiming the end of the Abrahamic covenant, the divinity of Christ, the docrtine of the Trinity—those Jews who converted to belief in Jesus were treated as apsotates. The situation was compounded by Christians themselves treating Jews with contempt. In the Christian Roman Empire, Constantine I forbade Christians to fellowship with Jews, preachers such as Saint John Chysostom preached firey sermons against Judaism, and Christian mobs sometimes destroyed Jewish synagogue at the urging of local bishops.

During the Spanish Inquisition, apostasy took on a new meaning. Forcing Jews to renounce their religion under threat of expulsion or even death complicated the issue of what qualified as "apostasy" in Judaism. Many rabbis generally considered the behavior of a Jew, rather than his professed public belief, to be the determining factor. Thus, large numbers of Jews became Marranos, publicly acting as Christian, but privately acting as Jews as best they could. On the other hand some well-known Jews converted to Christianity with enthusiasm and even engaged in public debates encouraging their fellow Jews to apostasize.

A partiularly well known case of apostasy was that of the Shabbatai Sevi in 1566. Shabbatai was a famous mystic and kabbalist, who was accepted by a large proporation of Jews as the Messiah until he apostasized to Islam.

It should also be noted that from the time of early Talmudic sages in the second century CE, the rabbis took the attitude than Jews could hold to a variety of theological attitudes and still be considered a Jew. In modern times, this attitude was exemplified by Abraham Isaac Kook (1864-1935), the first Chief Rabbi of the Jewish community in the British Mandate for Palestine, who held that even Jewish atheists were not apostate. Kook held that, in practice, atheists were actually helping true religion to burn away false images of God, thus in the end serving the purpose of true monotheism.

Sanctions against apostasy in Judaism today include the Othodox tradition of shunning a person who leaves the faith, in which the parents formally mourn their lost child and treat him or her as dead. Apostates in the State of Israel are forbidden to marry other Jews.

In Christianity

Apostasy in Christianity began early in its history. Saint Paul started out his career attempting to influence Christians to apostasize from the new faith (Acts 8) and revert to othodox Judaism. Ironically, when Christianity separated itself from Judaism, Jewish Christians who kept to the Mosaic traditions were considered either heretics or apostates.

In Christian tradition, apostates were to be shunned by other members of the church. Titus 3:10 indicates that an apostate or heretic needs to be "rejected after the first and second admonition." Hebrews 6:4-6 afirms the impossibility of those who have fallen away "to be brought back to repentance."

Many of the early martyrs died for their faith rather than apostasizing, but others gave in to the persecutors and offered sacrifice to the Roman gods. It is difficult to know how many quietly returned to pagan belief or to Judaism during the first centuries of Christian history.

With the conversion of Constantine I and the later establishment of Christianity as the official religion of the Roman state, the situation changed dramatically. Rather than being punished by the state if one refused to apostasize, a person would be sanctioned for apostasy, which became a civil offense punishable by law. This changed briefly under the administration of Emperior Julianus II (331-363 C.E.)—known to history as Julian the Apostate for his policy of divorcing the Roman state from its recent union with the Christian Church.

For more than a millennium afte Julian's death Christian states used the power of the sword to protect the Church against apostasy and heresy. Apostates were deprived of their civil as well as their religious rights. Torture was freely employed to extract confessions and to encourage recantations. Apostates and schismatics were not only excommunicated from the Church but persecuted by the state.

Apostasy on a grand scale took place several times. The “Great Schism” between Eastern Orthodoxy and Western Catholicism in the eighth century resulted in mutual excommunication. The Protestant Reformation in the sixteenth century further divided Christian against Christian. Each sectarian group claimed to have recovered the authentic faith and practice of the New Testament Church, thereby relegating rival versions of Christianity to the status of apostasy.

After decades of warfare in Europe, Christian tradition gradually came to accept the principle of tolerance and religioius freedom. Today, no major Christian denomination calls for legal sanctions against those who apostasize, although some denominations do excommunicate those who turn to other faiths, and some groups still practice shunning.

In Islam

Islam imposes harsh penalties for apostasy. The Qur'an has many passages that are critical of apostasy, but is silent on the proper punishment. In the Hadith, on the other hand, the death penalty is very explicit.

Today apostasy is punishable by death in Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Iran, Sudan, Afghanistan, Mauritania, and the Comoros. In Qatar apostasy is a also capital offense, but no executions have been reported for it. Most other Muslim states punish apostasy by both whipping and imprisonment.

A few examples of passages in the Qur'an relevant to apostasy:

- "Let there be no compulsion in the religion: Clearly the Right Path (i.e. Islam) is distinct from the crooked path." (2.256)

- "Those who reject faith after they accepted it, and then go on adding to their defiance of faith, never will their repentance be accepted; for they are those who have (purposely) gone astray." (3:90)

- "Those who believe, then reject faith, then believe (again) and (again) reject faith, and go on increasing in unbelief, Allah will not forgive them nor guide them on the way." (4:137)

The Hadith, the body of sayings and regulations attributed to Muhammad, mandates the death penalty for apostasy:

- Kill whoever changes his religion. (Sahih Bukhari 9:84:57)

- The blood of a Muslim... cannot be shed except in three cases: ...murder ...a married person who commits illegal sexual intercourse, and the one who reverts from Islam and leaves the Muslims. (Sahih Bukhari 9:83:17)

Some Muslim scholars argue that such traditions are not binding and can be updated to be brought into line with modern human rights standards. However, the majority still hold that if a Muslim consciously and without coercion declares his rejection of Islam, and does not change his mind, then the penalty for male apostates is death and for women it is life imprisonment.

Apostasy in Eastern religions

Oriental relgions normally do not sanction apostasy to the degree that Judaism and Christianity did in the past and Islam does today. However, people do apostasize from Eastern faiths. Evangelical Christian converts from Hinduism, for example, often testify to the depravity of the former lives as devotees of idolatry and polythesism. Converts from Buddhism likewise speak of the benefits of being liberated from the worship of "idols." Sikh communties have reported a rising problem of apostasy among their young people in recent years. [1]

Apostates from traditional faiths sometimes face serious sanctions if they marry members of an opposing faith. Hindu women in India who marry Muslim men, for example, sometimes face ostracism or worse from their clans. Sikhs who convert to Hinduism do so at the risk of not being welcome in their communities of origin. In authoritarian Buddhist countries, such as today's Burma, conversion to another religion likewise has serious social consequences.

New Religious Movements

As with Christianity in its early days, New Religious Movements (NRMs) face the problem of apostasy among their converts due to pressure from family, society, and members simply turning against their newfound faith.

A number of members of NRM members also apostasize under the pressure of deprogramming, in which they are kindapped by members of their families and forcibly confined in order to influence them to leave the group. Part of the "rehabilitation" process in deprogramming often involves requiring a person to publicly criticize his or her former religion—a true act of apostasy. In some cases, members of NRM "fake" apostasy in order to escape from forcible confinement and later return to their groups, but in other cases, the apostasy is real.

Some apostasy from New Religious Movements takes place through a process known as "exit counseling," which involves no kidnapping or forcible confinement. In other cases, NRM members decide to apostasize without any intense effort to inflence their leaving the group.

Apostates of NRMs may make a number of allegations against their former group and its leaders. This list includes one or more of the following: unkept promises, sexual abuse by the leader, irrational and contradictory teachings, deception, financial exploitation, demonizing of the outside world, abuse of power, hypocrisy of the leadership, unnecessary secrecy, discouragement of critical thinking, brainwashing, mind control, pedophilia, and a leadership that does not admit any mistakes.

While some of these allegations are based in fact, others are exaggerations and outright falsehoods. The roles that apostates play in opposition to NRMs are controversial subjects of debate among scholars of religion, sociologists and psychologists. One noted study proposes that stories of apostates are likely to paint a caricature of the group, shaped by the apostate's current role rather than his objective experience in the group. [2]

Sociologist Lewis A. Coser holds an apostate to be not just a person who experienced a dramatic change in conviction but one who, "is spiritually living... in the struggle against the old faith and for the sake of its negation."[3]

David Bromley defined the apostate role as follows and distinguished it from the defector and whistleblower roles.[4]

Stuart A. Wright asserts that apostasy is a unique phenomenon and a distinct type of religious defection, in which the apostate is a defector "who is aligned with an oppositional coalition in an effort to broaden the dispute, and embraces public claimsmaking activities to attack his or her former group." [5]

In International law

The United Nations, in its Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 18, affirmed the right of a person to change his religion, and thus to apostasize:

Everyone has the right to freedom of thought, conscience and religion; this right includes freedom to change his religion or belief, and freedom, alone or in community with others, and, in public or private, to manifest his religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship and observance.

The U.N. Commission on Human Rights claified that the recanting of a person's religion is a human right legally protected by the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights:

The Committee observes that the freedom to 'have or to adopt' a religion or belief necessarily entails the freedom to choose a religion or belief, including the right to replace one's current religion or belief with another or to adopt atheistic views [...] Article 18.2 bars coercion that would impair the right to have or adopt a religion or belief, including the use of threat of physical force or penal sanctions to compel believers or non-believers to adhere to their religious beliefs and congregations, to recant their religion or belief or to convert."[6]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Babinski, Edward (editor), Leaving the Fold: Testimonies of Former Fundamentalists. Prometheus Books, 2003. ISBN: 1591022177

- Bromley, David, The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements Westport, CT, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0275955087

- Elwell, Walter A. (Ed.) Baker Encyclopedia of the Bible, Volume 1 A-I, Baker Book House, 1988, pages 130-131, "Apostasy." ISBN 0801034477

- Lavallée, G. 1994 L'alliance de la brebis. Rescapée de la secte de Moïse, Montréal: Club Québec Loisirs (ex-Roch Theriault)

- Lucas, Phillip, NRMs in the 21st Century: legal, political, and social challenges in global perspective, 2004, ISBN 0-415-96577-2

- Wilson, S.G., Leaving the Fold: Apostates and Defectors in Antiquity. Augsburg Fortress Publishers, 2004. ISBN: 0800636759

- Wright, Stuart. Post-Involvement Attitudes of Voluntary Defectors from Controversial New Religious Movements. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 23 (1984): pp. 172-82

External Links

- Dunlop, Mark, The culture of Cults, 2001 [1]

- [Massimo Introvigne|Introvigne, Massimo Defectors, Ordinary Leavetakers and Apostates: A Quantitative Study of Former Members of New Acropolis in France - paper delivered at the 1997 Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Religion, San Francisco, November 23, 1997 [2]

- The Jewish Encyclopedia (1906). The Kopelman Foundation. [3]

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, The Odyssey of a New Religion: The Holy Order of MANS from New Age to Orthodoxy Indiana University press;

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, Shifting Millennial Visions in New Religious Movements: The case of the Holy Order of MANS in The year 2000: Essays on the End edited by Charles B. Strozier, New York University Press 1997;

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, The Eleventh Commandment Fellowship: A New Religious Movement Confronts the Ecological Crisis, Journal of Contemporary Religion 10:3, 1995:229-41;

- Lucas, Phillip Charles, Social factors in the Failure of New Religious Movements: A Case Study Using Stark's Success Model SYZYGY: Journal of Alternative Religion and Culture 1:1, Winter 1992:39-53

- Apostates of Islam, why Islam should be avoided [4]

- http://www.nccbuscc.org/nab/bible/deuteronomy/deuteronomy13.htm

- Pignotti, Monica, My nine lives in Scientology, 1989, [5]

- Wakefield, Margery, Testimony, 1996 [6]

- Lawrence Woodcraft, Astra Woodcraft, Zoe Woodcraft, The Woodcraft Family, Video Interviews [7]

- Islam and Apostasy Islam's affirmation of the Freedom of Faith and Freedom of Changing one's Faith

- The punishment of Apostasy in Islam

- Apostasy, Freedom and Da’wah: Full Disclosure in a Business-like Manner by Dr. Mohammad Omar Farooq

- World's #1 Muslim Debator advocates Capital Punishment for Apostates - Watch brief video

- Another known Muslim Scholar advocates Capital Punishment for Apostates - Watch brief video

- A video on "Apostasy & Holy Quran

- Back To Islam - Stories of ex-apostates of Islam

- Fatwa, Islam & freedom

- APOSTASY (IRTIDÃD) IN ISLAM: The act in which a Muslim abandons Islam

- Apostasy in Islam

- Apostasy From Islam

- ex-christian.net

- exchristian.org

- christianism.com

- Catholic Encyclopedia see Apostasy a Fide

- A list of apparent contradictions to be found if reading the 'Bible' as a literal and clear statement of fact

- Witnessing to Those Who Have Fallen From Faith J.P. Holding

- Information on a proposed procedure and the consequences of formally renouncing the Faith of the Catholic Church

- The CESNUR case website of Miguel Martinez, a critical former member of New Acropolis, who criticizes Massimo Introvigne's study of ex-members of New Acropolis and the assertions made by Bryan R. Wilson about apostates

- The Great Apostasy at the end of the age — Helpful quotes from article include: "He will establish his 666 economic system based on some sort of blood covenant marking of citizens. This will be the ultimate apostasy."

- More Apostasy from Islam

- Kaufmann, Inside Scientology/Dianetics: How I Joined Dianetics/Scientology and Became Superhuman, 1995 [8]

- Malinoski, Peter, Thoughts on Conducting Research with Former Cult Members , Cultic Studies Review, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2001 [9]

- Palmer, Susan J. Apostates and their Role in the Construction of Grievance Claims against the Northeast Kingdom/Messianic Communities [10]

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Barsarke, Alice. http://www.sikh-history.com/sikhhist/archivedf/feature-oct.html Apostasy and the Future of Sikhsim]. www.sikh-history.com. Retrieved August 30, 2007.

- ↑ in Bromley, David G et al. (ed.), Brainwashing Deprogramming Controversy: Sociological, Psychological, Legal, and Historical Perspectives (Studies in religion and society) p. 156, 1984, ISBN 0-88946-868-0

- ↑ Lewis A. Coser The Age of the Informer Dissent:1249-54, 1954

- ↑ Bromley, David G. (Ed.) The Politics of Religious Apostasy: The Role of Apostates in the Transformation of Religious Movements CT, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7

- ↑ Wright, Stuart, A., Exploring Factors that Shatpe the Apostate Role, in Bromley, David G., The Politics of Religious Apostasy, pp. 109, Praeger Publishers, 1998. ISBN 0-275-95508-7

- ↑ CCPR/C/21/Rev.1/Add.4, General Comment No. 22., 1993