Difference between revisions of "Phrenology" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

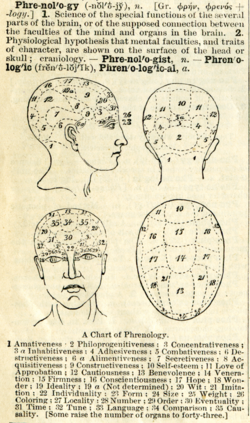

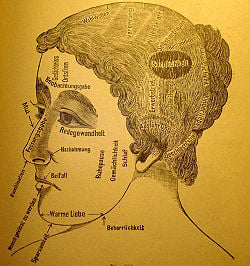

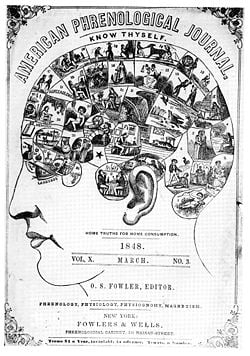

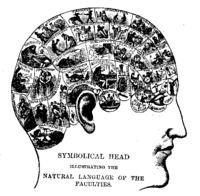

[[Image:Phrenology1.jpg|thumbnail|250px|right|A 19th century phrenology chart. The inscription on the neck reads, "[[Know yourself]]."]] | [[Image:Phrenology1.jpg|thumbnail|250px|right|A 19th century phrenology chart. The inscription on the neck reads, "[[Know yourself]]."]] | ||

| − | '''Phrenology''' | + | '''Phrenology''' is a theory which claims to be able to determine character, personality traits and criminality on the basis of the shape of the head (i.e., by reading "bumps" and "fissures"). Developed by German physician [[Franz Joseph Gall]] around 1800, phrenology was based on the concept that the [[brain]] is the organ of the [[mind]], and that certain brain areas have localized, specific [[Human brain#Function|functions]] (see in particular, [[Brodmann area|Brodmann's areas]]) or modules.<ref>Fodor, JA. (1983) The Modularity of Mind. MIT Press. See also, [[Modularity of mind]] p.14, 23, 131</ref> These areas were said to be proportional to a given individual's propensities and the importance of a given mental faculty, as well as the overall conformation of the cranial bone to reflect differences among individuals. |

| − | The discipline was very popular in the | + | The discipline was very popular in the nineteenth century, influencing early [[psychiatry]] and modern [[neuroscience]].<ref name="Simpson 2005">Simpson, D. (2005) Phrenology and the neurosciences: contributions of F. J. Gall and J. G. Spurzheim ANZ Journal of Surgery. Oxford. Vol.75.6; p.475 </ref> |

Phrenology, which focuses on personality and character, should be distinguished from [[craniometry]], which is the study of skull size, weight and shape, and [[physiognomy]], the study of facial features. However, these disciplines have claimed the ability to predict personality traits or intelligence (in fields such as [[anthropology]]/[[ethnology]]), and were sometimes posed to [[scientific racism|"scientifically" justify racism]]. | Phrenology, which focuses on personality and character, should be distinguished from [[craniometry]], which is the study of skull size, weight and shape, and [[physiognomy]], the study of facial features. However, these disciplines have claimed the ability to predict personality traits or intelligence (in fields such as [[anthropology]]/[[ethnology]]), and were sometimes posed to [[scientific racism|"scientifically" justify racism]]. | ||

| Line 16: | Line 16: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

[[Image:1895-Dictionary-Phrenolog.png|thumbnail|250px|right|A definition of phrenology with chart from Webster's Academic Dictionary, circa 1895]] | [[Image:1895-Dictionary-Phrenolog.png|thumbnail|250px|right|A definition of phrenology with chart from Webster's Academic Dictionary, circa 1895]] | ||

| − | Phrenology was not the first academic discipline to attempt to connect specific human characteristics with parts of the body: the [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] [[philosophy|philosopher]] [[Aristotle]] attempted to localize anger in the liver, and [[Renaissance]] medicine claimed that | + | Phrenology was not the first academic discipline to attempt to connect specific human characteristics with parts of the body: the [[Ancient Greece|Greek]] [[philosophy|philosopher]] [[Aristotle]] attempted to localize anger in the liver, and [[Renaissance]] medicine claimed that humans were composed of the [[Four humors]]. Phrenology was certainly influenced by these earlier practices. |

The [[Germany|German]] physician [[Franz Joseph Gall]] (1758-1828) was one of the first to consider the brain to be the source of all mental activity and is considered the founding father of phrenology. In the introduction to his main work ''The Anatomy and Physiology of the Nervous System in General, and of the Brain in Particular'', Gall makes the following statement in regard to his doctrinal principles, which comprise the intellectual foundation of phrenology: | The [[Germany|German]] physician [[Franz Joseph Gall]] (1758-1828) was one of the first to consider the brain to be the source of all mental activity and is considered the founding father of phrenology. In the introduction to his main work ''The Anatomy and Physiology of the Nervous System in General, and of the Brain in Particular'', Gall makes the following statement in regard to his doctrinal principles, which comprise the intellectual foundation of phrenology: | ||

| Line 30: | Line 30: | ||

Other significant authors on the subject include the [[Scotland|Scottish]] brothers [[George Combe]] (1788-1858) and [[Andrew Combe]] (1797-1847). George Combe was the author of some of the most popular works on phrenology and mental hygiene, e.g., ''The Constitution of Man'' and ''Elements of Phrenology''. | Other significant authors on the subject include the [[Scotland|Scottish]] brothers [[George Combe]] (1788-1858) and [[Andrew Combe]] (1797-1847). George Combe was the author of some of the most popular works on phrenology and mental hygiene, e.g., ''The Constitution of Man'' and ''Elements of Phrenology''. | ||

[[Image:COMBE.jpg|thumb|250px|left|George Combe was a writer on phrenology and education.]] | [[Image:COMBE.jpg|thumb|250px|left|George Combe was a writer on phrenology and education.]] | ||

| − | In the [[Victorian era|Victorian age]], phrenology was often taken quite seriously. Thousands of people consulted phrenologists to get advice in various matters, such as hiring personnel or finding suitable marriage partners. However, phrenology was rejected by mainstream academia, and was excluded from the [[British Association for the Advancement of Science]]. The popularity of phrenology fluctuated throughout the | + | In the [[Victorian era|Victorian age]], phrenology was often taken quite seriously. Thousands of people consulted phrenologists to get advice in various matters, such as hiring personnel or finding suitable marriage partners. However, phrenology was rejected by mainstream academia, and was excluded from the [[British Association for the Advancement of Science]]. The popularity of phrenology fluctuated throughout the nineteenth century, with some researchers comparing the field to [[astrology]], [[chiromancy]], or merely a fairground attraction, while others wrote serious scientific articles on the subject. Phrenology was also very popular in the United States, where automatic devices for phrenological analysis were devised. As in England, however, phrenology had a lackluster image in the eyes of the scientific community. |

| − | In the early | + | In the early twentieth century, phrenology benefited from revived interest, partly fueled by the studies of [[evolutionism]], [[criminology]] and [[anthropology]] (as pursued by [[Cesare Lombroso]]). The most prominent British phrenologist of the twentieth century was the famous [[London]] psychiatrist [[Bernard Hollander]] (1864-1934). His main works, ''The Mental Function of the Brain'' (1901) and ''Scientific Phrenology'' (1902) are an appraisal of the Gall's teachings. Hollander introduced a quantitative approach to the phrenological diagnosis, defining a methodology for measuring the skull, and comparing the measurements with statistical averages.<ref>"phrenology." The Oxford Companion to the Body. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2003. Answers.com 02 Oct. 2007. [[http://www.answers.com/topic/phrenology]]</ref> |

| − | Empirical refutation induced most scientists to abandon phrenology as a science by the early | + | Empirical refutation induced most scientists to abandon phrenology as a science by the early twentieth century. For example, various cases were observed of clearly aggressive persons displaying a well-developed "[[benevolence|benevolent organ]]," findings that contradicted the logic of the discipline. With advances in the studies of [[psychology]] and [[psychiatry]], many scientists became skeptical of the claim that human character can be determined by simple, external measures. |

==Methodology== | ==Methodology== | ||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

==Popular culture== | ==Popular culture== | ||

| − | Most often, phrenology was used in literature during the | + | Most often, phrenology was used in literature during the ninteenth century. Among some of the authors to use phrenological ideas were [[Charlotte Brontë]], as well as her two famous Bronte sisters, [[Arthur Conan Doyle]] and [[Edgar Allen Poe]].<ref>Erik Grayson. "Weird Science, Weirder Unity: Phrenology and Physiognomy in Edgar Allan Poe" ''Mode'' 1 (2005): 56-77. Also [http://www.arts.cornell.edu/english/mode/documents/grayson.html online].</ref> Whether these authors believed in the legitimacy of phrenology is open to debate; however, the criminological theorems that came from phrenology was often used to create an archetype of ninteenth century criminals. |

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

Revision as of 17:01, 20 October 2007

Phrenology is a theory which claims to be able to determine character, personality traits and criminality on the basis of the shape of the head (i.e., by reading "bumps" and "fissures"). Developed by German physician Franz Joseph Gall around 1800, phrenology was based on the concept that the brain is the organ of the mind, and that certain brain areas have localized, specific functions (see in particular, Brodmann's areas) or modules.[1] These areas were said to be proportional to a given individual's propensities and the importance of a given mental faculty, as well as the overall conformation of the cranial bone to reflect differences among individuals.

The discipline was very popular in the nineteenth century, influencing early psychiatry and modern neuroscience.[2] Phrenology, which focuses on personality and character, should be distinguished from craniometry, which is the study of skull size, weight and shape, and physiognomy, the study of facial features. However, these disciplines have claimed the ability to predict personality traits or intelligence (in fields such as anthropology/ethnology), and were sometimes posed to "scientifically" justify racism.

Etymology

The term phrenology comes from a combination of the Greek words φρήν, phrēn, which translates as "mind", and λόγος, logos, which means "knowledge". Phrenology, hence, is the study of the mind.[3]

History

Phrenology was not the first academic discipline to attempt to connect specific human characteristics with parts of the body: the Greek philosopher Aristotle attempted to localize anger in the liver, and Renaissance medicine claimed that humans were composed of the Four humors. Phrenology was certainly influenced by these earlier practices.

The German physician Franz Joseph Gall (1758-1828) was one of the first to consider the brain to be the source of all mental activity and is considered the founding father of phrenology. In the introduction to his main work The Anatomy and Physiology of the Nervous System in General, and of the Brain in Particular, Gall makes the following statement in regard to his doctrinal principles, which comprise the intellectual foundation of phrenology:

- That moral and intellectual faculties are innate

- That their exercise or manifestation depends on organization

- That the brain is the organ of all the propensities, sentiments and faculties

- That the brain is composed of as many particular organs as there are propensities, sentiments and faculties which differ essentially from each other.

- That the form of the head or cranium represents the form of the brain, and thus reflects the relative development of the brain organs.

Through careful observation and extensive experimentation, Gall believed he had linked aspects of character, called faculties, to precise organs in the brain. Gall's most important collaborator was Johann Spurzheim (1776-1832), who successfully disseminated phrenology in the United Kingdom and the United States. He popularized the term phrenology. One of the most significant developments to come out of phrenology was the movement away from considering the mind in an esoteric manner, but rather as an outgrowth of a physical organ (the brain), which could be studied with scientific observation and methodology. While not directly correlated, phrenology thus set the stage for the science of psychology.[4]

Other significant authors on the subject include the Scottish brothers George Combe (1788-1858) and Andrew Combe (1797-1847). George Combe was the author of some of the most popular works on phrenology and mental hygiene, e.g., The Constitution of Man and Elements of Phrenology.

In the Victorian age, phrenology was often taken quite seriously. Thousands of people consulted phrenologists to get advice in various matters, such as hiring personnel or finding suitable marriage partners. However, phrenology was rejected by mainstream academia, and was excluded from the British Association for the Advancement of Science. The popularity of phrenology fluctuated throughout the nineteenth century, with some researchers comparing the field to astrology, chiromancy, or merely a fairground attraction, while others wrote serious scientific articles on the subject. Phrenology was also very popular in the United States, where automatic devices for phrenological analysis were devised. As in England, however, phrenology had a lackluster image in the eyes of the scientific community.

In the early twentieth century, phrenology benefited from revived interest, partly fueled by the studies of evolutionism, criminology and anthropology (as pursued by Cesare Lombroso). The most prominent British phrenologist of the twentieth century was the famous London psychiatrist Bernard Hollander (1864-1934). His main works, The Mental Function of the Brain (1901) and Scientific Phrenology (1902) are an appraisal of the Gall's teachings. Hollander introduced a quantitative approach to the phrenological diagnosis, defining a methodology for measuring the skull, and comparing the measurements with statistical averages.[5]

Empirical refutation induced most scientists to abandon phrenology as a science by the early twentieth century. For example, various cases were observed of clearly aggressive persons displaying a well-developed "benevolent organ," findings that contradicted the logic of the discipline. With advances in the studies of psychology and psychiatry, many scientists became skeptical of the claim that human character can be determined by simple, external measures.

Methodology

Phrenology was a complex process that involved feeling the bumps in the skull to determine an individual's psychological attributes. Franz Joseph Gall first believed that the brain was made up of 27 individual 'organs' that created one's personality, with the first 19 of these 'organs' believed to exist in other animal species. Phrenologists would run their fingertips and palms over the skulls of their patients to feel for enlargements or indentations. The phrenologist would usually take measurements of the overall head size using a caliper. With this information, the phrenologist would assess the character and temperament of the patient and address each of the 27 "brain organs." This type of analysis was used to predict the kinds of relationships and behaviors to which the patient was prone. In its heyday during the 1820s-1840s, phrenology was often used to predict a child's future life, to assess prospective marriage partners and to provide background checks for job applicants.[6]

Gall's list of the "brain organs" was lengthy and specific, as he believed that each bump or indentation in a patient's skull corresponded to his "brain map." An enlarged bump meant that the patient utilized that particular "organ" extensively. The 27 areas were highly varied in function, from sense of color, to the likelihood of religiosity, to the potential to commit murder. Each of the 27 "brain organs" was found in a specific area of the skull. As the phrenologist felt the skull, he could refer to a numbered diagram showing where each functional area was believed to be located.[7]

The 27 "brain organs" were:

1. The instinct of reproduction (located in the cerebellum).

2. The love of one's offspring.

3. Affection and friendship.

4. The instinct of self-defense and courage; the tendency to get into fights.

5. The carnivorous instinct; the tendency to murder.

6. Guile; acuteness; cleverness.

7. The feeling of property; the instinct of stocking up on food (in animals); covetousness; the tendency to steal.

8. Pride; arrogance; haughtiness; love of authority; loftiness.

9. Vanity; ambition; love of glory (a quality "beneficent for the individual and for society").

10. Circumspection; forethought.

11. The memory of things; the memory of facts; educability; perfectibility.

12. The sense of places; of space proportions.

13. The memory of people; the sense of people.

14. The memory of words.

15. The sense of language; of speech.

16. The sense of colors.

17. The sense of sounds; the gift of music.

18. The sense of connectedness between numbers.

19. The sense of mechanics, of construction; the talent for architecture.

20. Comparative sagacity.

21. The sense of metaphysics.

22. The sense of satire; the sense of witticism.

23. The poetical talent.

24. Kindness; benevolence; gentleness; compassion; sensitivity; moral sense.

25. The faculty to imitate; the mimic.

26. The organ of religion.

27. The firmness of purpose; constancy; perseverance; obstinacy.

Criticisms

Phrenology has long been dismissed as a pseudoscience, in the wake of neurological advances. During the discipline's heyday, phrenologists including Gall committed many errors in the name of science. Phrenologists inferred dubious inferences between bumps in people's skulls and their personalities, claiming that the bumps were the determinant of personality. Some of the more valid assumptions of phrenology (e.g., that mental processes can be localized in the brain) remain in modern neuroimaging techniques and modularity of mind theory. Through advancements in modern medicine and neuroscience, the scientific community has generally concluded that feeling conformations of the outer skull is not an accurate predictor of behavior.

Phrenology was practiced by some scientists promoting racist ideologies. During the Victorian era, phrenology was sometimes invoked as a tool of social Darwinism, class division and other social practices which placed one group lower than another. African Americans were sometimes the target of phrenologically based racism. Later, Nazism incorporated phrenology into its pseudo-scientific claims. They used (often self-contradictory) phrenological claims, among other "biological evidence," as a "scientific" basis for Aryan racial superiority.

Popular culture

Most often, phrenology was used in literature during the ninteenth century. Among some of the authors to use phrenological ideas were Charlotte Brontë, as well as her two famous Bronte sisters, Arthur Conan Doyle and Edgar Allen Poe.[8] Whether these authors believed in the legitimacy of phrenology is open to debate; however, the criminological theorems that came from phrenology was often used to create an archetype of ninteenth century criminals.

Notes

- ↑ Fodor, JA. (1983) The Modularity of Mind. MIT Press. See also, Modularity of mind p.14, 23, 131

- ↑ Simpson, D. (2005) Phrenology and the neurosciences: contributions of F. J. Gall and J. G. Spurzheim ANZ Journal of Surgery. Oxford. Vol.75.6; p.475

- ↑ Phrenology. (n.d.). Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved October 02, 2007, from Dictionary.com website: [[1]]

- ↑ "phrenology." The Oxford Companion to the Body. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2003. Answers.com 02 Oct. 2007. [[2]]

- ↑ "phrenology." The Oxford Companion to the Body. Oxford University Press, 2001, 2003. Answers.com 02 Oct. 2007. [[3]]

- ↑ "phrenology." Encyclopedia of Occultism and Parapsychology. The Gale Group, Inc, 2001. Answers.com 02 Oct. 2007. [[4]]

- ↑ Cooter, Roger. "Cultural Meaning of Popular Science: Phrenology and the Organization of Consent in Nineteenth-Century Britain" (Cambridge University Press 2005) ISBN 9780521673297

- ↑ Erik Grayson. "Weird Science, Weirder Unity: Phrenology and Physiognomy in Edgar Allan Poe" Mode 1 (2005): 56-77. Also online.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Debby Applegate, The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher. Doubleday, 2006. Picture of Fowler Phrenology Head: Fowler Phrenology Head Stephen S. Carey, "The Beginner's Guide to Scientific Method." Thomson, 2004.

External links

- Readings in Phrenology, selections from texts by Johan Gaspar Spurzheim and George Combe.

- Phrenology Heads for Illustration, Large and small head.

- History of Phrenology on the Web by John van Wyhe, PhD. The most extensive source of phrenological texts available on the web.

- The Phrenology Pages, a Belgian site advocating phrenology.

- Phrenology. The History of Cerebral Localization. Article by Renato M.E. Sabbatini, PhD in Brain & Mind online article.

- Phrenology Today! Russian portal, advocating phrenology. Articles on so-called modern phrenology.

- Examples of phrenological tools can be seen in The Museum of Questionable Medical Devices, in Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

- Joseph Vimont: Traité de phrénologie humaine et comparée. (Paris, 1832-1835). Selected pages scanned from the original work. Historical Anatomies on the Web. US National Library of Medicine.

- Phrenology: History of a Classic Pseudoscience - by Steven Novella MD

- Historical Deadwood Newspaper accounts of C. R. Broadbent well known speaker on Phrenology and Physiology visit Deadwood SD 1878

- The Skeptic's Dictionary by Robert Todd Carroll

- Who Named It? Franz Joseph Gall Biography of Franz Joseph Gall and his creation: Phrenology.

- Phrenology by George Burgess (1829-1905) George Burgess, Phrenologist in Bristol, England 1861-1901.

- Corrective Phrenology

- Chart of the Phrenological Organs of the Brain

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.