Chaucer, Geoffrey

Nathan Cohen (talk | contribs) (Chaucher article established) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (40 intermediate revisions by 10 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | [[Image:Geoffrey Chaucer - Illustration from Cassell's History of England - Century Edition - published circa 1902.jpg| | + | {{Ebapproved}}{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}} |

| − | '''Geoffrey Chaucer''' (c. | + | {{epname|Chaucer, Geoffrey}} |

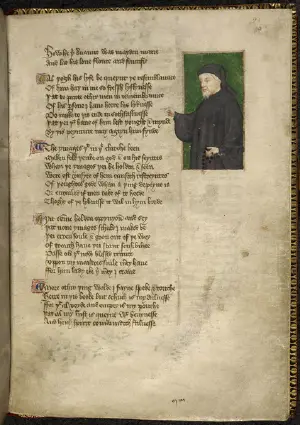

| + | [[Image:Geoffrey Chaucer - Illustration from Cassell's History of England - Century Edition - published circa 1902.jpg|300px|thumb|right|Chaucer: Illustration from Cassell's ''History of England,'' circa 1902.]] | ||

| + | '''Geoffrey Chaucer''' (c. 1343 – October 25, 1400) was an [[English literature|English author]], [[English poetry|poet]], [[philosopher]], [[Bureaucracy|bureaucrat]] ([[Noble court|courtier]]), and [[diplomat]], who is best known as the author of ''[[The Canterbury Tales]].'' As an author, he is considered not only the father of [[English literature]], but also, often of the [[English language]] itself. Chaucer's writings validated English as a language capable of poetic greatness, and in the process instituted many of the traditions of English poesy that have continued to this day. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | He was also, for a writer of his times, capable of powerful psychological insight. No other author of the [[Middle English]] period demonstrates the realism, nuance, and characterization found in Chaucer. [[Ezra Pound]] famously wrote that, although [[William Shakespeare|Shakespeare]] is often considered the great "psychologist" of English verse, "Don Geoffrey taught him everything he knew." | ||

==Life== | ==Life== | ||

| − | [[Image:Chaucer ellesmere.jpg|thumb|left|Chaucer as a pilgrim from the [[Ellesmere manuscript]]]] | + | [[Image:Chaucer ellesmere.jpg|thumb|left|300px|Chaucer as a [[pilgrim]] from the [[Ellesmere manuscript]]]] |

| − | Chaucer was born around | + | Chaucer was born around 1343. His father and grandfather were both London [[wine]] merchants and before that, for several generations, the family had been merchants in [[Ipswich]]. Although the Chaucers were not of noble birth, they were extremely well-to-do. |

| − | The young Chaucer began his career by becoming a [[page]] to | + | The young Chaucer began his career by becoming a [[page]] to Elizabeth de Burgh, fourth Countess of Ulster. In 1359, Chaucer traveled with Lionel of Antwerp, Elizabeth's husband, as part of the [[History of the British Army|English army]] in the [[Hundred Years' War]]. After his tour of duty, Chaucer traveled in [[France]], [[Spain]] and [[Flanders]], possibly as a messenger and perhaps as a religious pilgrim. In 1367, Chaucer became a valet to the royal family, a position which allowed him to travel with the king performing a variety of odd jobs. |

| − | On one such trip to Italy in 1373 | + | On one such trip to [[Italy]] in 1373, Chaucer came into contact with [[Middle Ages|medieval]] [[Italian poetry]], the forms and stories of which he would use later. While he may have been exposed to manuscripts of these works the trips were not usually long enough to learn sufficient [[Italian language|Italian]]; hence, it is speculated that Chaucher had learned Italian due to his upbringing among the merchants and immigrants in the docklands of London. |

| − | [[ | + | In 1374, Chaucer became Comptroller of the Customs for the port of [[London]] for [[Richard II]]. While working as comptroller Chaucer moved to [[Kent]] and became a [[Member of Parliament]] in 1386, later assuming the title of clerk of the king's works, a sort of foreman organizing most of the king's building projects. In this capacity he oversaw repairs upon [[Westminster Palace]] and [[St. George's Chapel]]. |

| − | + | Soon after the overthrow of his patron [[Richard II of England|Richard II]], Chaucer vanished from the historical record. He is believed to have died on October 25, 1400, of unknown causes, but there is no firm evidence for this date. It derives from the engraving on his tomb, built over one hundred years after his death. There is some speculation—most recently in Terry Jones' book ''Who Murdered Chaucer?: A Medieval Mystery''— that he was murdered by enemies of Richard II or even on the orders of Richard's successor, [[Henry IV of England|Henry IV]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Works== | ==Works== | ||

| − | Chaucer's first major work ''[[The Book of the Duchess]]'' was an [[elegy]] for [[Blanche of Lancaster]]. | + | Chaucer's first major work, ''[[The Book of the Duchess]],'' was an [[elegy]] for [[Blanche of Lancaster]], but reflects some of the signature techniques that Chaucer would deploy more deftly in his later works. It would not be long, however, before Chaucer would produce one of his most acclaimed masterpieces, ''[[Troilus and Criseyde]].'' Like many other works of his early period (sometimes called his French and Italian period) ''Troilus and Criseyde'' borrows its poetic structure from contemporary French and Italian poets and its subject matter from classical sources. |

| − | '' | + | ===''Troilus and Criseyde''=== |

| − | + | ''Troilus and Criseyde'' is the love story of [[Troilus]], a [[Troy|Trojan]] prince, and [[Cressida|Criseyde]]. Many Chaucer scholars regard the poem as his best for its vivid realism and (in comparison with later works) overall completeness as a story. | |

| − | + | Troilus is commanding an army battling the Greeks at the height of the [[Trojan War]] when he falls in love with Criseyde, a Greek woman captured and enslaved by his countrymen. Criseyde pledges her love to him, but when she is returned to the Greeks in a hostage exchange, she goes to live with the Greek hero, Diomedes. Troilus is infuriated, but can do nothing about it due to the siege of Troy. | |

| − | + | Meanwhile, an oracle prophesies that Troy will not be defeated as long as Troilus reaches the age of twenty alive. Shortly thereafter the Greek hero [[Achilles]] sees Troilus lead his horses to a fountain and falls in love with him. Achilles ambushes Troilus and his sister, Polyxena, who escapes. Troilus, however, rejects Achilles' advances, and takes refuge inside the temple of Apollo Timbraeus. | |

| − | + | Achilles, enraged at this rejection, slays Troilus on the altar. The Trojan heroes ride to the rescue too late, as Achilles whirls Troilus' head by the hair and hurls it at them. This affront to the god—killing his son and desecrating the temple—has been conjectured as the cause of Apollo's enmity towards Achilles, and, in Chaucer's poem, is used to tragically contrast Troilus' innocence and good-faith with Achilles' arrogance and capriciousness. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Chaucer's main source for the poem was [[Boccaccio]], who wrote the story in his ''Il Filostrato,'' itself a re-working of [[Benoît de Sainte-Maure]]'s ''Roman de Troie,'' which was in turn an expansion of a passage from [[Homer]]. | |

| − | === | + | ===''The Canterbury Tales''=== |

| − | [[ | + | |

| + | ''Troilus and Criseyde'' notwithstanding, Chaucer is almost certainly best known for his long poem, ''[[The Canterbury Tales]].'' | ||

| + | The poem consists of a collection of fourteen stories, two in [[prose]] and the rest in [[verse]]. The tales, some of which are original, are contained inside a [[frame tale]] told by a group of [[pilgrim]]s on their way from [[London Borough of Southwark|Southwark]] to [[Canterbury, Kent|Canterbury]] to visit the shrine of [[Saint]] [[Thomas à Becket]]'s at [[Canterbury Cathedral]]. | ||

| − | + | The poem is in stark contrast to other literature of the period in the naturalism of its narrative and the variety of the pilgrims and the stories they tell, setting it apart from almost anything else written during this period. The poem is concerned not with kings and gods, but with the lives and thoughts of everyday persons. Many of the stories narrated by the pilgrims seem to fit their individual characters and social standing, although some of the stories seem ill-fitting to their narrators, probably representing the incomplete state of the work. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Chaucer's experience in medieval society as page, soldier, messenger, valet, bureaucrat, foreman, and administrator undoubtedly exposed him to many of the types of people he depicted in the ''Tales.'' He was able to mimic their speech, satirize their manners, and use their idioms as a means for making art. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The themes of the tales vary, and include topics such as [[courtly love]], treachery, and avarice. The genres also vary, and include [[Romance (genre)|romance]], [[Breton lai]], [[sermon]], and [[fabliau]]. The characters, introduced in the General Prologue of the book, tell tales of great cultural relevance, and are among the most vivid accounts of medieval life available today. Chaucer provides a "slice-of-life," creating a picture of the times in which he lived by letting us hear the voices and see the viewpoints of people from all different backgrounds and social classes. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Some of the tales are serious and others humorous; however, all are very precise in describing the traits and faults of human nature. Chaucer, like virtually all other authors of his period, was very interested in presenting a moral to his story. Religious malpractice is a major theme, appropriate for a work written on the eve of [[The Reformation]]. Most of the tales are linked by similar themes and some are told in reprisal for other tales in the form of an argument. The work is incomplete, as it was originally intended that each character would tell four tales, two on the way to Canterbury and two on the return journey. This would have meant a possible one hundred and twenty tales which would have dwarfed the twenty-six tales actually completed. | |

| − | + | It is sometimes argued that the greatest contribution that ''The Canterbury Tales'' made to [[English literature]] was in popularizing the literary use of the [[vernacular]] language, [[English language|English]], as opposed to the [[French language|French]] or [[Latin]] then spoken by the noble classes. However, several of Chaucer's contemporaries—[[John Gower]], [[William Langland]], and [[the Pearl Poet]]—also wrote major literary works in English, and Chaucer's appellation as the "Father of English Literature," though partially true, is an overstatement. | |

| − | + | Much more important than standardization of dialect was the introduction, through ''The Canterbury Tales,'' of numerous poetic techniques that would become standards for English poesy. The poem's use of [[accentual-syllabic meter]], which had been invented a century earlier by the French and Italians, was revolutionary for English poesy. After Chaucer, the [[alliterative verse|alliterative meter]] of Old English poetry would become completely extinct. The poem also deploys, masterfully, [[iambic pentameter]], which would become the de facto measure for the English poetic line. (Five hundred years later, [[Robert Frost]] would famously write that there were two meters in the English language, "strict iambic and loose iambic.") Chaucer was the first author to write in English in pentameter, and ''The Canterbury Tales'' is his masterpiece of the technique. The poem is also one of the first in the language to use rhymed [[couplet|couplets]] in conjunction with a five-stress line, a form of rhyme that would become extremely popular in all varieties of English verse thereafter. | |

| − | + | ===Translation=== | |

| − | + | Chaucer, in his own time, was most famous as a translator of continental works. He translated such diverse works as [[Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius|Boethius’]] ''[[Consolation of Philosophy]]'' and ''[[The Romance of the Rose]],'' and the poems of [[Eustache Deschamps]], who wrote in a [[ballade]] that he considered himself a "nettle in Chaucer's garden of poetry." In recent times, however, the authenticity of some of Chaucer's translations have come into dispute, with some works putatively attributed to Chaucer having been proven to be authored by anonymous imitators. Furthermore, it is somewhat difficult for modern scholars to distinguish Chaucer's poetry from his translations; many of his most famous poems consist of long passages of direct translation from other sources. | |

| − | : | + | ==Influence== |

| + | ===Linguistic=== | ||

| + | [[File:Chaucer Hoccleve.png|thumb|300px|Portrait of Chaucer from [[Thomas Occleve]], a close friend]] | ||

| + | Chaucer wrote in continental accentual-syllabic [[meter (poetry)|meter]], a style which had developed since around the twelfth century as an alternative to the [[alliterative verse|alliterative]] [[Anglo-Saxon poetry|Anglo-Saxon meter]]. Chaucer is known for metrical innovation, inventing the [[rhyme royal]], and he was one of the first English poets to use the five-stress line, the [[iambic pentameter]], in his work, with only a few anonymous short works using it before him. The arrangement of these five-stress lines into rhyming [[couplet]]s was first seen in his ''[[The Legend of Good Women]].'' Chaucer used it in much of his later work. It would become one of the standard poetic forms in English. His early influence as a satirist is also important, with the common humorous device, the funny accent of a [[regional dialect]], apparently making its first appearance in ''[[The Reeve's Prologue and Tale|The Reeve's Tale]].'' | ||

| − | + | The poetry of Chaucer, along with other writers of the era, is credited with helping to ''standardize'' the London dialect of the [[Middle English]] language; a combination of Kentish and Midlands dialect. This is probably overstated: the influence of the court, [[chancery]], and bureaucracy—of which Chaucer was a part—remains a more probable influence on the development of [[Standard English]]. [[Modern English]] is somewhat distanced from the language of Chaucer's poems, owing to the effect of the [[Great Vowel Shift]] some time after his death. This change in the [[pronunciation]] of English, still not fully understood, makes the reading of Chaucer difficult for the modern audience. The status of the final ''-e'' in Chaucer's verse is uncertain: it seems likely that during the period of Chaucer's writing the final ''-e'' was dropping out of colloquial English and that its use was somewhat irregular. Chaucer's versification suggests that the final ''-e'' is sometimes to be vocalized, and sometimes to be silent; however, this remains a point on which there is disagreement. Apart from the irregular spelling, much of the vocabulary is recognizable to the modern reader. Chaucer is also recorded in the [[Oxford English Dictionary]] as the first author to use many common English words in his writings. These words were probably frequently used in the language at the time but Chaucer, with his ear for common speech, is the earliest manuscript source. ''Acceptable, alkali, altercation, amble, angrily, annex, annoyance, approaching, arbitration, armless, army, arrogant, arsenic, arc, artillery, and aspect'' are just some of those from the first letter of the alphabet. | |

| − | + | ====Literary==== | |

| − | + | [[Chaucer]]'s early popularity is attested by the many poets who imitated his works. [[John Lydgate]] was one of earliest imitators who wrote a continuation to the ''Tales.'' Later, a group of poets including [[Gavin Douglas]], [[William Dunbar]], and [[Robert Henryson]] were known as the [[Scottish Chaucerians]] for their indebtedness to his style. Many of the manuscripts of Chaucer's works contain material from these admiring poets. The later [[romantic era]] poets' appreciation of Chaucer was colored by the fact that they did not know which of the works were genuine. It was not until the late nineteenth century that the official Chaucerian canon, accepted today, was decided upon. One hundred and fifty years after his death, ''The Canterbury Tales'' was selected by [[William Caxton]] to be one of the first books to be printed in England. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | ==== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Historical Representations and Context=== | |

| + | Early on, representations of Chaucer began to circle around two co-existing identities: 1) a courtier and a king's man, an international humanist familiar with the classics and continental greats; 2) a man of the people, a plain-style satirist and a critic of the church. All things to all people, for a combination of mixed aesthetic and political reasons, Chaucer was held in high esteem by high and low audiences—certainly a boon for printers and booksellers. His enduring popularity is attested to by the fact that in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Chaucer was printed more than any other English author. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Major Works== |

The following major works are in rough chronological order but scholars still debate the dating of most of Chaucer's output and works made up from a collection of stories may have been compiled over a long period. | The following major works are in rough chronological order but scholars still debate the dating of most of Chaucer's output and works made up from a collection of stories may have been compiled over a long period. | ||

| − | + | * Translation of ''[[Roman de la Rose]]'', possibly extant as ''[[The Romaunt of the Rose]]'' | |

| − | * Translation of [[Roman de la Rose]], possibly extant as [[The Romaunt of the Rose]] | + | * ''[[The Book of the Duchess]]'' |

| − | * [[The Book of the Duchess]] | + | * ''[[The House of Fame]]'' |

| − | * [[The House of Fame]] | + | * ''[[Anelida and Arcite]]'' |

| − | * [[Anelida and Arcite]] | + | * ''[[The Parliament of Fowls]]'' |

| − | * [[The Parliament of Fowls]] | + | * Translation of [[Boethius]]' ''[[Consolation of Philosophy]]'' as ''[[Boece (Chaucer)|Boece]]'' |

| − | * Translation of [[Boethius]]' [[Consolation of Philosophy]] as [[Boece (Chaucer)|Boece]] | + | * ''[[Troilus and Criseyde]]'' |

| − | * [[Troilus and Criseyde]] | + | * ''[[The Legend of Good Women]]'' |

| − | * [[The Legend of Good Women]] | + | * ''[[Treatise on the Astrolabe]]'' |

| − | * [[Treatise on the Astrolabe]] | + | * ''[[The Canterbury Tales]]'' |

| − | * [[The Canterbury Tales]] | ||

| − | + | ===Short poems=== | |

*''An ABC'' | *''An ABC'' | ||

*''Chaucers Wordes unto Adam, His Owne Scriveyn'' | *''Chaucers Wordes unto Adam, His Owne Scriveyn'' | ||

| Line 110: | Line 101: | ||

*''Womanly Noblesse'' | *''Womanly Noblesse'' | ||

| − | + | ===Poems dubiously ascribed to Chaucer=== | |

*''Against Women Unconstant'' | *''Against Women Unconstant'' | ||

*''A Balade of Complaint'' | *''A Balade of Complaint'' | ||

| Line 116: | Line 107: | ||

*''Merciles Beaute'' | *''Merciles Beaute'' | ||

*''The Visioner's Tale'' | *''The Visioner's Tale'' | ||

| − | *''The Equatorie of the Planets'' | + | *''The Equatorie of the Planets''—Rumored to be a rough translation of a Latin work derived from an Arab work of the same title. It is a description of the construction and use of what is called an “equatorium planetarum,” and was used in calculating planetary orbits and positions (at the time it was believed the sun orbited the Earth). The belief this work is ascribed to Chaucer comes from similar “treatise” on the Astrolabe. However, the evidence Chaucer wrote such a work is questionable, and as such is not included in ''The Riverside Chaucer.'' If Chaucer did not compose this work, it was probably written by a contemporary (Benson, perhaps). |

| − | + | ===Works mentioned by Chaucer, presumed lost=== | |

| − | *''Of the Wreched Engendrynge of Mankynde'' | + | *''Of the Wreched Engendrynge of Mankynde,'' possible translation of [[Innocent III]]'s ''De miseria conditionis humanae'' |

*''Origenes upon the Maudeleyne'' | *''Origenes upon the Maudeleyne'' | ||

| − | *''The | + | *''The Book of the Leoun''—An interesting argument. ''The Book of the Leon'' is mentioned in Chaucer's retraction at the end of ''The Canterbury Tales.'' It is likely he wrote such a work; one suggestion is that the work was such a bad piece of writing it was lost, but if so, Chaucer would not have included it in the middle of his retraction. Indeed, he would not have included it at all. A likely source dictates it was probably a “redaction” of Guillaume de Machaut's ''Dit dou lyon,'' a story about courtly love, a subject about which Chaucer scholars agree that he frequently wrote (Le Romaunt de Rose). |

| − | + | ===Pseudepigraphies and Works Plagiarizing Chaucer=== | |

| − | *''[[The Pilgrim's Tale]]'' | + | *''[[The Pilgrim's Tale]]''—Written in the sixteenth century with many Chaucerian allusions |

| − | *''[[The Plowman's Tale]]'' | + | *''[[The Plowman's Tale]]'' aka [http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/plwtlint.htm ''The Complaint of the Ploughman'']—A [[Lollard]] [[satire]] later appropriated as a [[Protestant]] text |

| − | *''[[Pierce the Ploughman's Crede]]'' | + | *''[[Pierce the Ploughman's Crede]]''—A Lollard satire later appropriated by Protestants |

| − | *[http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/plgtlint.htm ''The Ploughman's Tale''] | + | *[http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/plgtlint.htm ''The Ploughman's Tale'']—Its body is largely a version of [[Thomas Hoccleve]]'s "Item de Beata Virgine." |

| − | *[http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/sym4int.htm "La Belle Dame Sans Merci"] | + | *[http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/sym4int.htm "La Belle Dame Sans Merci"]—Richard Roos' translation of a poem of the same name by Alain Chartier |

| − | *''[http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/shoaf.htm The Testament of Love]'' | + | *''[http://www.lib.rochester.edu/camelot/teams/shoaf.htm The Testament of Love]''—Actually by [[Thomas Usk]] |

| − | *''[[Jack Upland]]'' | + | *''[[Jack Upland]]''—A Lollard satire |

| − | *''[[God Spede the Plow]]'' | + | *''[[God Spede the Plow]]''—Borrows parts of Chaucer's ''Monk's Tale'' |

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | *Johnson, Ian (ed.). ''Geoffrey Chaucer in Context''. Cambridge University Press, 2021. ISBN 978-1009010603 |

| − | + | *Turner, Marion. ''Chaucer: A European Life''. Princeton University Press, 2019. ISBN 0691160090 | |

| − | + | *Wallace, David. ''Geoffrey Chaucer: A Very Short Introduction''. Oxford University Press, 2019. ISBN 978-0198767718 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved April 18, 2024. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | + | *[https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/144 Books by Chaucer, Geoffrey] ''Project Gutenberg''} |

* [http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/ Anthology of Middle English Literature] | * [http://www.luminarium.org/medlit/ Anthology of Middle English Literature] | ||

| − | * [ | + | * [https://www.bartleby.com/212/0703.html Early Editions of Chaucer] |

| + | * [https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/geoffrey-chaucer Geoffrey Chaucer] ''Poetry Foundation'' | ||

| + | * [https://poets.org/poet/geoffrey-chaucer Geoffrey Chaucer] ''Academy of American Poets'' | ||

| − | + | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{credit|44323621}} | |

Latest revision as of 06:52, 18 April 2024

Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1343 – October 25, 1400) was an English author, poet, philosopher, bureaucrat (courtier), and diplomat, who is best known as the author of The Canterbury Tales. As an author, he is considered not only the father of English literature, but also, often of the English language itself. Chaucer's writings validated English as a language capable of poetic greatness, and in the process instituted many of the traditions of English poesy that have continued to this day.

He was also, for a writer of his times, capable of powerful psychological insight. No other author of the Middle English period demonstrates the realism, nuance, and characterization found in Chaucer. Ezra Pound famously wrote that, although Shakespeare is often considered the great "psychologist" of English verse, "Don Geoffrey taught him everything he knew."

Life

Chaucer was born around 1343. His father and grandfather were both London wine merchants and before that, for several generations, the family had been merchants in Ipswich. Although the Chaucers were not of noble birth, they were extremely well-to-do.

The young Chaucer began his career by becoming a page to Elizabeth de Burgh, fourth Countess of Ulster. In 1359, Chaucer traveled with Lionel of Antwerp, Elizabeth's husband, as part of the English army in the Hundred Years' War. After his tour of duty, Chaucer traveled in France, Spain and Flanders, possibly as a messenger and perhaps as a religious pilgrim. In 1367, Chaucer became a valet to the royal family, a position which allowed him to travel with the king performing a variety of odd jobs.

On one such trip to Italy in 1373, Chaucer came into contact with medieval Italian poetry, the forms and stories of which he would use later. While he may have been exposed to manuscripts of these works the trips were not usually long enough to learn sufficient Italian; hence, it is speculated that Chaucher had learned Italian due to his upbringing among the merchants and immigrants in the docklands of London.

In 1374, Chaucer became Comptroller of the Customs for the port of London for Richard II. While working as comptroller Chaucer moved to Kent and became a Member of Parliament in 1386, later assuming the title of clerk of the king's works, a sort of foreman organizing most of the king's building projects. In this capacity he oversaw repairs upon Westminster Palace and St. George's Chapel.

Soon after the overthrow of his patron Richard II, Chaucer vanished from the historical record. He is believed to have died on October 25, 1400, of unknown causes, but there is no firm evidence for this date. It derives from the engraving on his tomb, built over one hundred years after his death. There is some speculation—most recently in Terry Jones' book Who Murdered Chaucer?: A Medieval Mystery— that he was murdered by enemies of Richard II or even on the orders of Richard's successor, Henry IV.

Works

Chaucer's first major work, The Book of the Duchess, was an elegy for Blanche of Lancaster, but reflects some of the signature techniques that Chaucer would deploy more deftly in his later works. It would not be long, however, before Chaucer would produce one of his most acclaimed masterpieces, Troilus and Criseyde. Like many other works of his early period (sometimes called his French and Italian period) Troilus and Criseyde borrows its poetic structure from contemporary French and Italian poets and its subject matter from classical sources.

Troilus and Criseyde

Troilus and Criseyde is the love story of Troilus, a Trojan prince, and Criseyde. Many Chaucer scholars regard the poem as his best for its vivid realism and (in comparison with later works) overall completeness as a story.

Troilus is commanding an army battling the Greeks at the height of the Trojan War when he falls in love with Criseyde, a Greek woman captured and enslaved by his countrymen. Criseyde pledges her love to him, but when she is returned to the Greeks in a hostage exchange, she goes to live with the Greek hero, Diomedes. Troilus is infuriated, but can do nothing about it due to the siege of Troy.

Meanwhile, an oracle prophesies that Troy will not be defeated as long as Troilus reaches the age of twenty alive. Shortly thereafter the Greek hero Achilles sees Troilus lead his horses to a fountain and falls in love with him. Achilles ambushes Troilus and his sister, Polyxena, who escapes. Troilus, however, rejects Achilles' advances, and takes refuge inside the temple of Apollo Timbraeus.

Achilles, enraged at this rejection, slays Troilus on the altar. The Trojan heroes ride to the rescue too late, as Achilles whirls Troilus' head by the hair and hurls it at them. This affront to the god—killing his son and desecrating the temple—has been conjectured as the cause of Apollo's enmity towards Achilles, and, in Chaucer's poem, is used to tragically contrast Troilus' innocence and good-faith with Achilles' arrogance and capriciousness.

Chaucer's main source for the poem was Boccaccio, who wrote the story in his Il Filostrato, itself a re-working of Benoît de Sainte-Maure's Roman de Troie, which was in turn an expansion of a passage from Homer.

The Canterbury Tales

Troilus and Criseyde notwithstanding, Chaucer is almost certainly best known for his long poem, The Canterbury Tales. The poem consists of a collection of fourteen stories, two in prose and the rest in verse. The tales, some of which are original, are contained inside a frame tale told by a group of pilgrims on their way from Southwark to Canterbury to visit the shrine of Saint Thomas à Becket's at Canterbury Cathedral.

The poem is in stark contrast to other literature of the period in the naturalism of its narrative and the variety of the pilgrims and the stories they tell, setting it apart from almost anything else written during this period. The poem is concerned not with kings and gods, but with the lives and thoughts of everyday persons. Many of the stories narrated by the pilgrims seem to fit their individual characters and social standing, although some of the stories seem ill-fitting to their narrators, probably representing the incomplete state of the work.

Chaucer's experience in medieval society as page, soldier, messenger, valet, bureaucrat, foreman, and administrator undoubtedly exposed him to many of the types of people he depicted in the Tales. He was able to mimic their speech, satirize their manners, and use their idioms as a means for making art.

The themes of the tales vary, and include topics such as courtly love, treachery, and avarice. The genres also vary, and include romance, Breton lai, sermon, and fabliau. The characters, introduced in the General Prologue of the book, tell tales of great cultural relevance, and are among the most vivid accounts of medieval life available today. Chaucer provides a "slice-of-life," creating a picture of the times in which he lived by letting us hear the voices and see the viewpoints of people from all different backgrounds and social classes.

Some of the tales are serious and others humorous; however, all are very precise in describing the traits and faults of human nature. Chaucer, like virtually all other authors of his period, was very interested in presenting a moral to his story. Religious malpractice is a major theme, appropriate for a work written on the eve of The Reformation. Most of the tales are linked by similar themes and some are told in reprisal for other tales in the form of an argument. The work is incomplete, as it was originally intended that each character would tell four tales, two on the way to Canterbury and two on the return journey. This would have meant a possible one hundred and twenty tales which would have dwarfed the twenty-six tales actually completed.

It is sometimes argued that the greatest contribution that The Canterbury Tales made to English literature was in popularizing the literary use of the vernacular language, English, as opposed to the French or Latin then spoken by the noble classes. However, several of Chaucer's contemporaries—John Gower, William Langland, and the Pearl Poet—also wrote major literary works in English, and Chaucer's appellation as the "Father of English Literature," though partially true, is an overstatement.

Much more important than standardization of dialect was the introduction, through The Canterbury Tales, of numerous poetic techniques that would become standards for English poesy. The poem's use of accentual-syllabic meter, which had been invented a century earlier by the French and Italians, was revolutionary for English poesy. After Chaucer, the alliterative meter of Old English poetry would become completely extinct. The poem also deploys, masterfully, iambic pentameter, which would become the de facto measure for the English poetic line. (Five hundred years later, Robert Frost would famously write that there were two meters in the English language, "strict iambic and loose iambic.") Chaucer was the first author to write in English in pentameter, and The Canterbury Tales is his masterpiece of the technique. The poem is also one of the first in the language to use rhymed couplets in conjunction with a five-stress line, a form of rhyme that would become extremely popular in all varieties of English verse thereafter.

Translation

Chaucer, in his own time, was most famous as a translator of continental works. He translated such diverse works as Boethius’ Consolation of Philosophy and The Romance of the Rose, and the poems of Eustache Deschamps, who wrote in a ballade that he considered himself a "nettle in Chaucer's garden of poetry." In recent times, however, the authenticity of some of Chaucer's translations have come into dispute, with some works putatively attributed to Chaucer having been proven to be authored by anonymous imitators. Furthermore, it is somewhat difficult for modern scholars to distinguish Chaucer's poetry from his translations; many of his most famous poems consist of long passages of direct translation from other sources.

Influence

Linguistic

Chaucer wrote in continental accentual-syllabic meter, a style which had developed since around the twelfth century as an alternative to the alliterative Anglo-Saxon meter. Chaucer is known for metrical innovation, inventing the rhyme royal, and he was one of the first English poets to use the five-stress line, the iambic pentameter, in his work, with only a few anonymous short works using it before him. The arrangement of these five-stress lines into rhyming couplets was first seen in his The Legend of Good Women. Chaucer used it in much of his later work. It would become one of the standard poetic forms in English. His early influence as a satirist is also important, with the common humorous device, the funny accent of a regional dialect, apparently making its first appearance in The Reeve's Tale.

The poetry of Chaucer, along with other writers of the era, is credited with helping to standardize the London dialect of the Middle English language; a combination of Kentish and Midlands dialect. This is probably overstated: the influence of the court, chancery, and bureaucracy—of which Chaucer was a part—remains a more probable influence on the development of Standard English. Modern English is somewhat distanced from the language of Chaucer's poems, owing to the effect of the Great Vowel Shift some time after his death. This change in the pronunciation of English, still not fully understood, makes the reading of Chaucer difficult for the modern audience. The status of the final -e in Chaucer's verse is uncertain: it seems likely that during the period of Chaucer's writing the final -e was dropping out of colloquial English and that its use was somewhat irregular. Chaucer's versification suggests that the final -e is sometimes to be vocalized, and sometimes to be silent; however, this remains a point on which there is disagreement. Apart from the irregular spelling, much of the vocabulary is recognizable to the modern reader. Chaucer is also recorded in the Oxford English Dictionary as the first author to use many common English words in his writings. These words were probably frequently used in the language at the time but Chaucer, with his ear for common speech, is the earliest manuscript source. Acceptable, alkali, altercation, amble, angrily, annex, annoyance, approaching, arbitration, armless, army, arrogant, arsenic, arc, artillery, and aspect are just some of those from the first letter of the alphabet.

Literary

Chaucer's early popularity is attested by the many poets who imitated his works. John Lydgate was one of earliest imitators who wrote a continuation to the Tales. Later, a group of poets including Gavin Douglas, William Dunbar, and Robert Henryson were known as the Scottish Chaucerians for their indebtedness to his style. Many of the manuscripts of Chaucer's works contain material from these admiring poets. The later romantic era poets' appreciation of Chaucer was colored by the fact that they did not know which of the works were genuine. It was not until the late nineteenth century that the official Chaucerian canon, accepted today, was decided upon. One hundred and fifty years after his death, The Canterbury Tales was selected by William Caxton to be one of the first books to be printed in England.

Historical Representations and Context

Early on, representations of Chaucer began to circle around two co-existing identities: 1) a courtier and a king's man, an international humanist familiar with the classics and continental greats; 2) a man of the people, a plain-style satirist and a critic of the church. All things to all people, for a combination of mixed aesthetic and political reasons, Chaucer was held in high esteem by high and low audiences—certainly a boon for printers and booksellers. His enduring popularity is attested to by the fact that in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, Chaucer was printed more than any other English author.

Major Works

The following major works are in rough chronological order but scholars still debate the dating of most of Chaucer's output and works made up from a collection of stories may have been compiled over a long period.

- Translation of Roman de la Rose, possibly extant as The Romaunt of the Rose

- The Book of the Duchess

- The House of Fame

- Anelida and Arcite

- The Parliament of Fowls

- Translation of Boethius' Consolation of Philosophy as Boece

- Troilus and Criseyde

- The Legend of Good Women

- Treatise on the Astrolabe

- The Canterbury Tales

Short poems

- An ABC

- Chaucers Wordes unto Adam, His Owne Scriveyn

- The Complaint unto Pity

- The Complaint of Chaucer to his Purse

- The Complaint of Mars

- The Complaint of Venus

- A Complaint to His Lady

- The Former Age

- Fortune

- Gentilesse

- Lak of Stedfastnesse

- Lenvoy de Chaucer a Scogan

- Lenvoy de Chaucer a Bukton

- Proverbs

- To Rosemounde

- Truth

- Womanly Noblesse

Poems dubiously ascribed to Chaucer

- Against Women Unconstant

- A Balade of Complaint

- Complaynt D'Amours

- Merciles Beaute

- The Visioner's Tale

- The Equatorie of the Planets—Rumored to be a rough translation of a Latin work derived from an Arab work of the same title. It is a description of the construction and use of what is called an “equatorium planetarum,” and was used in calculating planetary orbits and positions (at the time it was believed the sun orbited the Earth). The belief this work is ascribed to Chaucer comes from similar “treatise” on the Astrolabe. However, the evidence Chaucer wrote such a work is questionable, and as such is not included in The Riverside Chaucer. If Chaucer did not compose this work, it was probably written by a contemporary (Benson, perhaps).

Works mentioned by Chaucer, presumed lost

- Of the Wreched Engendrynge of Mankynde, possible translation of Innocent III's De miseria conditionis humanae

- Origenes upon the Maudeleyne

- The Book of the Leoun—An interesting argument. The Book of the Leon is mentioned in Chaucer's retraction at the end of The Canterbury Tales. It is likely he wrote such a work; one suggestion is that the work was such a bad piece of writing it was lost, but if so, Chaucer would not have included it in the middle of his retraction. Indeed, he would not have included it at all. A likely source dictates it was probably a “redaction” of Guillaume de Machaut's Dit dou lyon, a story about courtly love, a subject about which Chaucer scholars agree that he frequently wrote (Le Romaunt de Rose).

Pseudepigraphies and Works Plagiarizing Chaucer

- The Pilgrim's Tale—Written in the sixteenth century with many Chaucerian allusions

- The Plowman's Tale aka The Complaint of the Ploughman—A Lollard satire later appropriated as a Protestant text

- Pierce the Ploughman's Crede—A Lollard satire later appropriated by Protestants

- The Ploughman's Tale—Its body is largely a version of Thomas Hoccleve's "Item de Beata Virgine."

- "La Belle Dame Sans Merci"—Richard Roos' translation of a poem of the same name by Alain Chartier

- The Testament of Love—Actually by Thomas Usk

- Jack Upland—A Lollard satire

- God Spede the Plow—Borrows parts of Chaucer's Monk's Tale

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Johnson, Ian (ed.). Geoffrey Chaucer in Context. Cambridge University Press, 2021. ISBN 978-1009010603

- Turner, Marion. Chaucer: A European Life. Princeton University Press, 2019. ISBN 0691160090

- Wallace, David. Geoffrey Chaucer: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2019. ISBN 978-0198767718

External links

All links retrieved April 18, 2024.

- Books by Chaucer, Geoffrey Project Gutenberg}

- Anthology of Middle English Literature

- Early Editions of Chaucer

- Geoffrey Chaucer Poetry Foundation

- Geoffrey Chaucer Academy of American Poets

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.