Jakarta

| Jakarta Daerah Khusus Ibu Kota Jakarta |

|||

| Special Capital Territory of Jakarta | |||

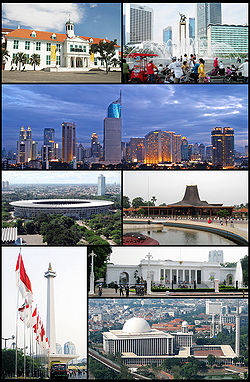

| (From top, left to right): Jakarta Old Town, Hotel Indonesia Roundabout, Jakarta Skyline, Gelora Bung Karno Stadium, Taman Mini Indonesia Indah, Monumen Nasional, Merdeka Palace, Istiqlal Mosque | |||

|

|||

| Nickname: The Big Durian[1] | |||

| Motto: Jaya Raya (Indonesian) (Victorious and Great) |

|||

| Location of Jakarta in Indonesia | |||

| Coordinates: 6¬į12‚Ä≤S 106¬į48‚Ä≤E | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Indonesia | ||

| Province | Jakarta ň° | ||

| Government | |||

|  - Type | Special administrative area | ||

|  - Acting Governor | Heru Budi Hartono | ||

| Area | |||

|  - City | 664.01 km² (256.4 sq mi) | ||

|  - Land | 662.33 km² (255.7 sq mi) | ||

|  - Water | 6,977.5 km² (2,694 sq mi) | ||

|  - Urban | 3,540 km² (1,367 sq mi) | ||

|  - Metro | 7,062.5 km² (2,726.8 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 7 m (23 ft) | ||

| Population (mid-2021 estimate) | |||

|  - City | 10,187,595 | ||

|  - Density | 15,978/km² (41,382.8/sq mi) | ||

|  - Urban | 34,540,000 | ||

|  - Urban Density | 9,756/km² (25,267.9/sq mi) | ||

|  - Metro | 33,430,285 | ||

|  - Metro Density | 4,733/km² (12,258.4/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | WIT (UTC+7) | ||

| Area code(s) | +62 21 | ||

| ň° Jakarta is not part of any province, it is controlled directly under the government and is designated a Special Capital Territory | |||

| Website: www.jakarta.go.id (official site) | |||

Jakarta (also DKI Jakarta), formerly known as Djakarta, Sunda Kelapa, Jayakarta and Batavia is the capital and largest city of Indonesia. Located on the northwest coast of the island of Java, Jakarta was established in 397 C.E., as Sunda Pura, the capital of the kingdom of Tarumanagara. During the sixteenth century it became an important trading outpost for the British and for the Dutch, who named it ‚ÄúBatavia‚ÄĚ in 1619. The city was renamed "Jakarta" by the Japanese during WWII during the Japanese occupation of Indonesia. In 1950, once independence was secured, Jakarta was made the national capital of Indonesia.

Jakarta faces many of the challenges of large cities in developing nations, with a burgeoning population whose rapid growth overwhelms public services, roads and infrastructure. With an area of 661.52 km² and a population of over 10 million, Jakarta is the most populous city in Indonesia and in Southeast Asia. Its metropolitan area, Jabotabek, contains more than 23 million people, and is part of an even larger Jakarta-Bandung megalopolis. Since 2004, Jakarta, under the governance of Sutiyoso, has built a new transportation system, which is known as "TransJakarta" or "Busway." Jakarta is the location of the Jakarta Stock Exchange and the Monumen Nasional (National Monument of Indonesia), and hosted the 1962 Asian Games.

History

Early history

The earliest record mentioning this area as a capital city can be traced to the Indianized kingdom of Tarumanagara as early as the fourth century. In 397 C.E., King Purnawarman established Sunda Pura as a new capital city for the kingdom, located on the northern coast of Java.[2] Purnawarman left seven memorial stones with inscriptions bearing his name spread across the area, including the present-day Banten and West Java provinces. The Tugu Inscription is considered the oldest of all of them.[3]

After the power of Tarumanagara power declined, all of its territory, including Sunda Pura, fell under the Kingdom of Sunda. The harbor area was renamed ‚ÄúSunda Kalapa,‚ÄĚ according to a Hindu monk's lontar manuscripts, which are now located at the Oxford University Library in England, and travel records by Prince Bujangga Manik.[4]

By the fourteenth century, Sunda Kalapa had become a major trading port and a principal outlet for pepper for the Hindu kingdom of Pajajaran (1344 ‚Äď 1570s).[5]The first European fleet, four Portuguese ships from Malacca, arrived in 1513 when the Portuguese were looking for a route for spices and especially pepper.[6]

In 1522, another Portuguese named Enrique Leme visited Sunda with the intention of establishing trading rights. He was well-received and the Portuguese were given rights to build a warehouse and expand their fort in Sunda Kelapa The Kingdom of Sunda made a peace agreement with Portugal and allowed the Portuguese to build a port in hopes that it would help to defend them against the rising power of the Muslim Sultanate of Demak in central Java. In 1527, Muslim troops from Cirebon and Demak, under the leadership of Fatahillah, attacked the Kingdom of Sunda. They conquered Sunda Kelapa on June 22, 1557, and changed its name to "Jayakarta" ("Great Deed" or "Complete Victory").[7]

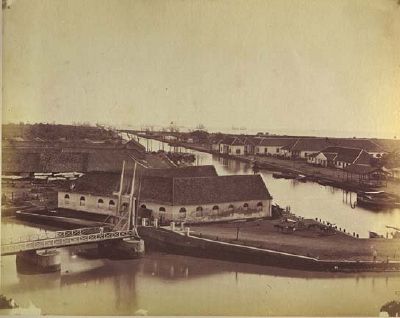

Dutch and British colonization

Through the relationship with Prince Jayawikarta from the Sultanate of Banten, Dutch ships arrived in Jayakarta in 1596. In 1602, the British East India Company's first voyage, commanded by Sir James Lancaster, arrived in Aceh and sailed on to Banten where they were allowed to build a trading post. This site became the center of British trade in Indonesia until 1682.[8]

In 1615, Prince Jayawikarta allowed the English to build houses directly across from the Dutch buildings in Jayakarta. Later, when relations between Prince Jayawikarta and the Dutch deteriorated, his soldiers attacked the Dutch fortress, which included two main buildings, Nassau and Mauritus. Even with the help of fifteen British ships, Prince Jayakarta's army wasn't able to defeat the Dutch. Jan Pieterszoon Coen (J.P. Coen) arrived in Jayakarta just in time, burned the English trading post, and forced the British to retreat in their ships.

The Sultan of Banten sent his soldiers to summon Prince Jayawikarta and reprimanded him for establishing a close relationship with the British without the approval of the Banten authorities. Prince Jayawikarta was exiled in Tanara, a small town in Banten, until his death, and the relationship of the British with the Banten government was weakened, allowing the Dutch to dominate. In 1916, the Dutch changed the name of Jayakarta to "Batavia," which it remained until 1942.[9]

Within Batavia's walls, wealthy Dutch built tall houses and pestilential canals. Commercial opportunities attracted Indonesian and especially Chinese immigrants, in increasing numbers which created burdens on the city. Tensions grew as the colonial government tried to restrict Chinese migration through deportations. On October 9, 1740, five thousand Chinese were massacred and the following year, Chinese inhabitants were moved to Glodok outside the city walls.[10] Epidemics in 1835 and 1870 encouraged more people to move far south of the port. The Koningsplein, now Merdeka Square, was completed in 1818, and Kebayoran Baru was the last Dutch-built residential area.[10]

World War II and modern history

The city was renamed "Jakarta" by the Japanese during their World War II occupation of Indonesia. Following World War II, Indonesian Republicans withdrew from allied-occupied Jakarta during their fight for Indonesian independence and established their capital in Yogyakarta. In 1950, once independence was secured, Jakarta was once again made the national capital.[10] Indonesia's founding president, Sukarno, envisaged Jakarta as a great international city. He initiated large government-funded projects undertaken with openly nationalistic and modernist architecture.[11][12] Projects in Jakarta included a clover-leaf highway, a major boulevard (Jalan Sudirman), monuments such as The National Monument, major hotels, and a new parliament building.

In 1966, Jakarta was declared a "special capital city district" (daerah khusus ibukota), thus gaining a status approximately equivalent to that of a state or province. Lieutenant General Ali Sadikin served as Governor from this time until 1977; he rehabilitated roads and bridges, encouraged the arts, built several hospitals and a large number of new schools. He also cleared out slum dwellers for new development projects‚ÄĒsome for the benefit of the Suharto family[13]‚ÄĒand tried to eliminate rickshaws and ban street vendors. He began control of migration to the city in order to stem the overcrowding and poverty.[14] Land redistribution, reforms in the financial sector, and foreign investment contributed to a real estate boom which changed the appearance of the city.

The boom in development ended with the 1997/98 East Asian Economic crisis, putting Jakarta at the center of violence, protest, and political maneuvering. Long-time president, Suharto, began to lose his grip on power. Tensions reached a peak in May 1998, when four students were shot dead at Trisakti University by security forces; four days of riots ensued resulting in the loss of an estimated 1,200 lives and 6,000 buildings damaged or destroyed. Suharto resigned as president, and Jakarta has remained the focal point of democratic change in Indonesia. [15] A number of Jemaah Islamiah-connected bombings have occurred in the city since 2000.[10]

Administration

Officially, Jakarta is not a city but a province with special status as the capital of Indonesia. It is administered in much the same way as any other Indonesian province. Jakarta has a governor (instead of a mayor), and is divided into several sub-regions with their own administrative systems. Jakarta, as a province, is divided into five cities (kota) (formerly ‚Äúmunicipality‚ÄĚ), each headed by a mayor, and one regency (‚Äúkabupaten‚ÄĚ) headed by a regent. In August 2007, Jakarta held its first gubernatorial election, which was won by Fauzi Bowo. The city's governors had previously been appointed by the local parliament. The election was part of a country-wide decentralization drive to allow for direct local elections in several areas.[16]

List of cities of Jakarta:

- Central Jakarta (Jakarta Pusat)

- East Jakarta (Jakarta Timur)

- North Jakarta (Jakarta Utara)

- South Jakarta (Jakarta Selatan)

- West Jakarta (Jakarta Barat)

The only regency of Jakarta is:

- Thousand Islands (Kepulauan Seribu), formerly a subdistrict of North Jakarta.

Culture

As the economic and political capital of Indonesia, Jakarta attracts many foreign as well as domestic immigrants. As a result, Jakarta has a decidedly cosmopolitan flavor and a diverse culture. Many of the immigrants are from the other parts of Java, bringing along a mixture of dialects of the Javanese and Sundanese languages, as well as their traditional foods and customs. The Betawi (Orang Betawi, or "people of Batavia") is a term used to describe the descendants of the people living around Batavia since around the eighteenth century. The Betawi people are mostly descended from various Southeast Asian ethnic groups brought or attracted to Batavia to meet the demand for labor, and includes people from various parts of Indonesia. The language and culture of these immigrants are distinct from those of the Sundanese or Javanese. There has also been a Chinese community in Jakarta for centuries. Officially they make up 6 percent of the Jakarta population, though this number may be under- reported.[17]

Jakarta has several performing arts centers, including the Senayan center. Traditional music, including wayang and gamelan performances, can often be heard at high-class hotels. As the largest Indonesian city, Jakarta has lured talented musicians and artisans from many regions, who come to the city hoping to find a greater audience and more opportunities for success.

The concentration of wealth and political influence in the city means that foreign influence on its landscape and culture, such as the presence of international fast-food chains, is much more noticeable than in the more rural areas of Indonesia.

Transportation

There are railways throughout Jakarta; however, they are inadequate in providing transportation for the citizens of Jakarta; during peak hours, the number of passengers simply exceeds its capacity. Railroads connect Jakarta to its neighboring cities: Depok and Bogor to the south, Tangerang and Serpong to the west, and Bekasi, Karawang, and Cikampek to the east. The major rail stations are Gambir, Jatinegara, Pasar Senen, Manggarai, Tanah Abang and Jakarta Kota.

Trans Jakarta operates a special bus-line called Busway. The Busway takes less than half an hour to traverse a route which would normally take more than an hour during peak hours. Construction of the 2nd and 3rd corridor routes of the Busway was completed in 2006, serving the route from Pulogadung to Kalideres. The busway serving the route from Blok M to Jakarta Kota has been operational since January 2004.

Despite the presence of many wide roads, Jakarta suffers from congestion due to heavy traffic, especially in the central business district. To reduce traffic jams, some major roads in Jakarta have a 'three in one' rule during rush hours, first introduced in 1992, prohibiting less than three passengers per car on certain roads. In 2005, this rule covered the Gatot Subroto Road. This ruling has presented an economic opportunity for "joki" (meaning "jockey"), who wait at the entry points to restricted areas and charge a fee to sit in cars which have only one or two occupants while they drive through.

Jakarta's roads are notorious for the undisciplined behavior of drivers; the rules of the road are broken with impunity and police bribery is commonplace. The painted lines on the road are regarded as mere suggestions, as vehicles often travel four or five abreast on a typical two-lane road, and it is not uncommon to encounter a vehicle traveling the wrong direction. In recent years, the number of motorcycles on the streets has been growing almost exponentially. The vast sea of small, 100-200cc motorcycles, many of which have 2-stroke motors, create much of the traffic, noise and air pollution that plague Jakarta.

An outer ring road is now being constructed and is partly operational from Cilincing-Cakung-Pasar Rebo-Pondok Pinang-Daan Mogot-Cengkareng. A toll road connects Jakarta to Soekarno-Hatta International Airport in the north of Jakarta. Also connected via toll road is the port of Merak and Tangerang to the west; and Bekasi, Cibitung and Karawang, Purwakarta and Bandung to the east.

Two lines of the Jakarta Monorail are planned: the green line serving Semanggi-Casablanca Road-Kuningan-Semanggi and the blue line serving Kampung Melayu-Casablanca Road-Tanah Abang-Roxy. In addition, there are plans for a two-line subway (MRT) system, with a north-south line between Kota and Lebak Bulus, with connections to both monorail lines; and an east-west line, which will connect with the north-south line at the Sawah Besar station. The current project, which began construction in 2005, has been halted due to a lack of funds and its future remains uncertain.

On June 6, 2007, the city administration introduced the Waterway, a new river boat service along the Ciliwung river, [18] intended to reduce the traffic snarls in Jakarta.

There are currently two airports serving Jakarta; Soekarno-Hatta International Airport (CGK) and Halim Perdanakusuma International Airport (HLP). Soekarno-Hatta International Airport is used for both private and commercial airliners connecting Jakarta with other Indonesian cities. It is also Indonesia's main international gateway. Halim Perdanakusuma International Airport serves mostly private and presidential flights.

Cycle rickshaws, called becak (‚Äúbechak‚ÄĚ), provide local transportation in the back streets of some parts of the city. From the early 1940s to 1991 they were a common form of local transportation in the city. In 1966, an estimated 160,000 rickshaws were operating in the city; as much as fifteen percent of Jakarta's total workforce was engaged in rickshaw driving. In 1971, rickshaws were banned from major roads, and shortly thereafter the government attempted a total ban, which substantially reduced their numbers but did not eliminate them. An especially aggressive campaign to eliminate them finally succeeded in 1990 and 1991, but during the economic crisis of 1998, some returned amid less effective government attempts to control them.[19] The only place left in Jakarta where riding becak is permitted is the amusement park Taman Impian Jaya Ancol.

Education

Jakarta is the home of many universities, the oldest of which are state University of Indonesia (UI) and the private-owned Universitas Nasional (UNAS), much of which has now relocated to Pasar Minggu. There are also many other private universities in Jakarta. As the largest city and the capital, Jakarta houses a large number of students from various parts of Indonesia, many of whom reside in dormitories or home-stay residences. Similarly to other large cities in developing Asian countries, there is a large number of professional schools teaching a wide range of subjects from Mandarin, English and computer skills to music and dance. For basic education, there are a variety of public (national), private (national and bi-lingual national plus) and international primary and secondary schools.

Sports

Since Soekarno's era, Jakarta has often been chosen as the venue for international sport events. Jakarta hosted the Asian Games in 1962, and was host of the regional Sea Games several times. Jakarta is also home of several professional soccer clubs. The most popular of them is Persija, which regularly plays its matches in the Lebak Bulus Stadium. The biggest stadium in Jakarta is the Stadion Utama Bung Karno with a capacity of 100,000 seats The Kelapa Gading Sport Mall in Kelapa Gading, North Jakarta, with a capacity of 7,000 seats, is the home arena of the Indonesian national basketball team. Many international basketball matches are played in this stadium. The Senayan sports complex, built in 1959 to accommodate the 1962 Asian Games, is comprised of several sport venues including the Bung Karno soccer stadium, Madya Stadium, Istora Senayan, a shooting range, a tennis court and a golf driving range.

Media

Newspapers

Jakarta has several daily newspapers including Bisnis Indonesia, The Jakarta Post, Indo Pos, Seputar Indonesia, Kompas, Media Indonesia, Republika, Pos Kota, Warta Kota, and Suara Pembaruan.

Television

Government television: TVRI.

Private national television: TPI (Indonesia), RCTI, Metro TV, Indosiar, StarANTV, SCTV (Indonesia), Trans TV, Lativi, Trans 7, and Global TV.

Local television: Jak-TV, O-Channel, and Space-Toon.

Cable television: Indovision, ASTRO, TelkomVision, Kabelvision

Problems of Urbanization

Like many big cities in developing countries, Jakarta suffers from major urbanization problems. The population has risen sharply from 1.2 million in 1960 to 8.8 million in 2004, counting only its legal residents. The population of greater Jakarta is estimated at 23 million, making it the fourth largest urban area in the world. The rapid population growth has overwhelmed the government's ability to provide basic needs for its residents. As the third biggest economy in Indonesia, Jakarta attracts a large number of visitors. The population during weekends is almost double that of weekdays, due to the influx of residents residing in other areas of Jabotabek. Because of government's inability to provide adequate transportation for its large population, Jakarta also suffers from severe traffic jams that occur almost every day. Air pollution and garbage management is also a severe problem.

During the wet season, Jakarta suffers from flooding due to clogged sewage pipes and waterways. Deforestation due to rapid urbanization on the highland areas south of Jakarta near Bogor and Depok has also contributed to the floods.

Sister Cities

Jakarta has sister relationships with a number of towns and regions worldwide:

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

Jeddah, Saudi Arabia Beijing, China

Beijing, China Berlin, Germany

Berlin, Germany Istanbul, Turkey

Istanbul, Turkey Los Angeles, United States

Los Angeles, United States State of New South Wales, Australia

State of New South Wales, Australia Paris, France

Paris, France Rotterdam, the Netherlands

Rotterdam, the Netherlands Seoul, South Korea

Seoul, South Korea Tokyo, Japan

Tokyo, Japan

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Travel Indonesia Guide ‚Äď How to appreciate the ‚ÄėBig Durian‚Äô Jakarta Worldstepper, April 8, 2008.

- ‚ÜĎ Sundakala: cuplikan sejarah Sunda berdasarkan naskah-naskah ‚ÄúPanitia Wangsakerta‚ÄĚ Cirebon. (Jakarta: Yayasan Pustaka Jaya, 2005).

- ‚ÜĎ The Sunda Kingdom of West Java From Tarumanagara to Pakuan Pajajaran with the Royal Center of Bogor (Yayasan Cipta Loka Caraka, 2007).

- ‚ÜĎ Three Old Sundanese Poems (KITLV Press, 2007).

- ‚ÜĎ Keat Gin Ooi, Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2004, ISBN 1576077705), 227.

- ‚ÜĎ Sumber-sumber asli sejarah Jakarta, Jilid I: Dokumen-dokumen sejarah Jakarta sampai dengan akhir abad ke-16 (Cipta Loka Caraka, 1999).

- ‚ÜĎ Recognizing the Sunda Kelapa Padrao Inscription August 33, 2022. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ M.C. Ricklefs, A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, 2nd Edition (London: MacMillan, 1993, ISBN 0333576896), 29.

- ‚ÜĎ Jayakarta becomes Batavia - Batavia becomes Jakarta! The rise and fall of Empires Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 Patrick Witton, Indonesia (Melbourne: Lonely Planet, 2003, ISBN 1740591542), 138-139.

- ‚ÜĎ Abidin Kusno, Behind the Postcolonial: Architecture, Urban Space and Political Cultures (NY: Routledge, 2000, ISBN 0415236150).

- ‚ÜĎ Peter Schoppert and Soedarmadji Damais Java Style (Periplus Editions, 1998, ISBN 9625932321).

- ‚ÜĎ M. Douglas, "The Environmental Sustainability of Development. Coordination, Incentives and Political Will in Land Use Planning for the Jakarta Metropolis." Third World Planning Review 11(2) (1989): 211‚Äď38; M. Douglas, "The Political Economy of Urban Poverty and Environmental Management in Asia: Access, Empowerment and Community-based Alternatives," Environment and Urbanization 4(2) (1992): 9‚Äď32.

- ‚ÜĎ Peter Turner, Java (Melbourne: Lonely Planet, 1997, ISBN 0864423144), 315.

- ‚ÜĎ Theodore Friend, Indonesian Destinies (Harvard University Press, 2003, ISBN 0674011376), 329.

- ‚ÜĎ Jakarta holds historic election BBC, August 8, 2007. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Tim Johnston, Chinese diaspora: Indonesia BBC, March 3, 2005. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Lucy Williamson, Jakarta begins river boat service BBC, June 6, 2007. Retrieved March 28, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Yoshifumi Azuma, Urban peasants: beca drivers in Jakarta (Jakarta: Pustaka Sinar Harapan, 2003).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Abeyasekere, Susan. Jakarta a history. Singapore: Oxford University Press, 1987. ISBN 0195826884

- Blussé, Leonard, and Menghong Chen. The archives of the Kong Koan of Batavia. Sinica Leidensia, v. 59. Leiden: Brill, 2003. ISBN 9004131574

- Friend, Theodore. Indonesian Destinies. Harvard University Press, 2003. ISBN 0674011376

- Gugler, Josef (ed.). World cities beyond the West globalization, development, and inequality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004. ISBN 0521830036

- Kusno, Abidin. Behind the Postcolonial: Architecture, Urban Space and Political Cultures. NY: Routledge, 2000. ISBN 0415236150

- Ooi, Keat Gin. 2004. Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 1576077705

- Ricklefs, M.C. A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan, 1993. ISBN 0333576896

- Schoppert, Peter, and Soedarmadji Damais. Java Style. Periplus Editions, 1998. ISBN 9625932321

- Taylor, Jean Gelman. The social world of Batavia European and Eurasian in Dutch Asia. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983. ISBN 0299094707

- Turner, Peter. Jakarta: a Lonely Planet city guide. Hawthorn, Vic: Lonely Planet Publications, 1995. ISBN 9780864422903

- Turner, Peter. Java. Melbourne: Lonely Planet, 1997. ISBN 0864423144

- Witton, Patrick. Indonesia. Melbourne: Lonely Planet, 2003. ISBN 1740591542

External links

All links retrieved December 17, 2024.

-

- Mapping from Multimap or GlobalGuide or Google Maps

- Satellite image from WikiMapia

- Mapping from OpenStreetMap.

| Cities and regency of Jakarta |

|---|

| Cities: Central Jakarta | East Jakarta | North Jakarta | South Jakarta | West Jakarta |

| Regency: Thousand Islands |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.