Tel Dan Stele

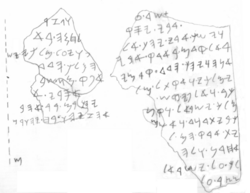

The Tel Dan Stele was a black basalt stele erected by an Aramaean (Syrian) king in northernmost Israel, containing an Aramaic inscription to commemorate his victory over the ancient Hebrews. Fragments of the stele, which has been dated to the ninth or eighth century B.C.E., were discovered at Tel Dan in 1993 and 1994.

Although the name of the author does not appear on the existing fragments, he is probably Hazael, a king of neighboring Aram Damascus. The stele affirms that, during a time of war between Israel and Syria, the god Hadad had made the author king and given him victory. In the process, he had killed King Joram of Israel and his ally, King Ahaziah of the "House of David."

In the Bible, Hazael came to the throne after being appointed by the Israelite prophet Elisha to overthrow his predecessor, Ben-Hadad II. However, the Bible attributes the killing of Joram and Ahaziah to the action of the Israelite usurper Jehu, likewise at the behest of the prophet Elisha. The Bible confirms that Jehu later lost considerable amounts of northern territory to Hazael. As Dan lay just inside Israel's territory between Damascus and Jehu's capital of Samaria, this makes Hazael's erecting a victory monument at Dan highly plausible.

The inscription has generated great interest because of its apparent reference to the "House of David," constituting the earliest known confirmation outside of the Bible of the Davidic dynasty.

Background

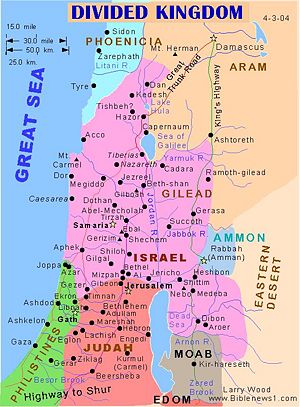

The stele was discovered at Tel Dan, previously named Tell el-Qadi, an archaeological site in Israel in the upper Galilee next to the Golan Heights. The site is quite securely identified with the biblical city of Dan, where an important Israelite shrine once stood.

Fragment A was discovered accidentally in 1993 in a stone wall near a related archaeological dig at Tel Dan. Fragments B1 and B2, which fit together, were discovered in 1994. There is a possible fit between fragment A and the assembled fragments B1/B2, but it is uncertain and disputed. If the fit is correct, then the pieces were originally side by side.

The stele was apparently broken into pieces at some point and later used in a construction project at Tel Dan, presumably by Hebrew builders. The eighth century limit as the most recent date for the stele was determined by a destruction layer caused by a well-documented Assyrian conquest in 733/732 B.C.E.

The period of Aramean (Syrian) supremacy and military conquest against the kingdoms of Judah and Israel, as depicted in the Tel Dan Stele, is dated to ca. 841-798 B.C.E., corresponding to the beginning of the reign of Jehu, King of Israel (841-814 B.C.E.), until the end of the reign of his successor, Jehoahaz (814/813-798 B.C.E.). This also corresponds to the end of the reigns of both King Ahaziah of Judah, who was indeed of the House of David (843-842 B.C.E.) and the reign of Joram of Israel (851-842 B.C.E.). (This chronology was based on the posthumously published work of Yohanan Aharoni (Tel Aviv University) and Michael Avi-Yonah, in collaboration with Anson F. Rainey and Ze'ev Safrai and was published in 1993, before the discovery of the Tel Dan Stele.)

Only portions of the inscription remain, but it has generated much excitement among those interested in biblical archaeology. Attention has concentrated on the Semitic letters ביתדוד, which are identical to the Hebrew for "house of David." If the reading is correct, it is the first time that the name "David" has been clearly recognized at any archaeological site. Like the Mesha Stele, the Tel Dan Stele seems typical of a memorial intended as a sort of military propaganda, which boasts of its author's victories.

The stele's account

A line by line translation by André Lemaire is as follows (with text missing from the stele, or too damaged by erosion to be legible, represented by "[.....]"):

- [.....................].......[...................................] and cut [.........................]

- [.........] my father went up [....................f]ighting at/against Ab[....]

- And my father lay down; he went to his [fathers]. And the king of I[s-]

- rael penetrated into my father's land[. And] Hadad made me—myself—king.

- And Hadad went in front of me[, and] I departed from ...........[.................]

- of my kings. And I killed two [power]ful kin[gs], who harnessed two thou[sand cha-]

- riots and two thousand horsemen. [I killed Jo]ram son of [Ahab]

- king of Israel, and I killed [Achaz]yahu son of [Joram kin]g

- of the House of David. And I set [.......................................................]

- their land ...[.......................................................................................]

- other ...[......................................................................... and Jehu ru-]

- led over Is[rael...................................................................................]

- siege upon [............................................................]

Biblical parallels

The Tel Dan inscription apparently coincides with certain events recorded in the Old Testament, though the poor state of preservation of the fragments has engendered much contention on this issue. The most direct parallel between the Tel Dan writings and the Bible presumes that the author is indeed Hazael. In this case, "my father" refers to Ben-Hadad II, whom the Bible speaks of as being ill prior to Hazael's accession to the throne. While the Bible attributes the killing of Joram of Israel and Ahaziah of Judah to the military commander and future king of Israel Jehu, the Tel Dan inscription gives the credit to its own author. One way of interpreting this discrepancy is that Hazael may have seen Jehu as his agent. Alternatively, Hazael may simply have claimed credit for Jehu's deeds, or the Bible may attribute to Jehu deeds actually done by Hazael.

In the Bible, 2 Kings 8:7-15 tells how the Israelite prophet Elisha appointed Hazael to become king of Syria in order to punish Israel for her sins. While war raged between Syria on one side and the combined forces of Israel and Judah on the other, the present Syrian king, Ben-Hadad, lay ill in Damascus. To obtain a favorable prognosis, he sent Hazael with a generous gift to Elisha, who happened to be in the area:

Hazael went to meet Elisha, taking with him as a gift of forty camel-loads of all the finest wares of Damascus. He went in and stood before him, and said, "Your son Ben-Hadad king of Aram has sent me to ask, 'Will I recover from this illness?'" Elisha answered, "Go and say to him, 'You will certainly recover'; but the Lord has revealed to me that he will in fact die."

Elisha then prophesied that Hazael himself would become king and wreak havoc against Israel, predicting that "You will set fire to their fortified places, kill their young men with the sword, dash their little children to the ground, and rip open their pregnant women." Hazael returned to Ben-Hadad and reported: "He told me that you would certainly recover." The next day, however, Hazael murdered Ben-Hadad by suffocating him and succeeded him as king.

Elisha soon commanded the Israelite commander Jehu to usurp the throne of Israel. Jehu immediately complied, killing both Joram of Israel and his ally, Ahaziah of Judah, in the process (2 Kings 8:28 and 2 Kings 9:15-28). Jehu was hailed by the biblical writers as a champion of God who destroyed the Temple of Baal in the Israelite capital of Samaria and did away with the descendants of King Ahab—including Joram, his mother Jezebel, and 60 of his kinsmen.

However, the Tel Dan Stele appears to put events in a very different light, with Hazael himself claiming credit for the deaths of Joram and Ahaziah. In any case, the biblical account admits that Jehu's army was defeated by Hazael "throughout all of the territories of Israel." This makes Hazael's capture of Tel Dan—the site of a major Israelite shrine—very likely. The weakened Jehu, meanwhile, seems to have turned at some point to Assyria for support against Damascus, as the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III depicts him as humbly offering tribute to the Assyrian king.

The "House of David"

Far less interest has been raised about the above-mentioned Syrian view of the deaths of Joram and Ahaziah than about the apparent mention in the Tel Dan Stele of the "House of David." The majority of archaeologists and epigraphers hold to this reading of the text. However some scholars object to this reading on literary grounds.

In favor of the reading "House of David," archaeologist William Dever argues that unbiased analysts universally agree with the reading. Those who deny it tend to belong to the ultra-critical Copenhagen School which denies that the Bible has any usefulness as a historical source:

On the "positivist" side of the controversy, regarding the authenticity of the inscription, we now have published opinions by most of the world's leading epigraphers.…: The inscription means exactly what it says. On the "negativist" side, we have the opinions of Thompson, Lemche, and Cryer of the Copenhagen School. The reader may choose (Dever 2003, 128-129).

The critics have suggested other readings of ביתדוד, usually based on the fact that the written form "DWD" can be rendered both as David and as Dod (Hebrew for "beloved") or related forms. It is agreed by most scholars, however, that even assuming "of the house of David" is the correct readying, this does not prove the existence of an literal Davidic dynasty, only that the kings of Judah were known as belonging to such a "house."

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Athas, George. The Tel Dan Inscription: A Reappraisal and a New Interpretation. Journal for the study of the Old Testament supplement series, 360. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0826460561.

- Bartusch, Mark W. Understanding Dan: An Exegetical Study of a Biblical City, Tribe and Ancestor. Journal for the study of the Old Testament, 379. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0826466570.

- Biran, Avraham. Biblical Dan. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1994. ISBN 978-9652210203.

- Dever, William G. Who Were the Early Israelites, and Where Did They Come from? Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Pub. Co, 2003. ASIN B001IAYVQ0

- Hagelia, Hallvard. The Tel Dan Inscription. Uppsala: Uppsala Univ. Library, 2006. ISBN 978-9155466138.

- Stith, D. Matthew. The Coups of Hazael and Jehu: Building an Historical Narrative. Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2008. ISBN 978-1593338336.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.