Shapur I

Shapur I was the second King of the Second Persian Empire. The dates of his reign are commonly given as 241-272, but it is likely that he also reigned as co-regent (together with his father, Ardashir I) prior to his father's death in 241. Shapur built on his father's successes, further extending and consolidating the empire. At the time, the Roman Empire was in chaos; he took advantage of this to invade and conquer several eastern provinces, including Armenia, parts of Syria and Anatolia. Gordian III won some victories but was finally defeated (244) and his successor Philip the Arab sued for peace. In 260, Shapur famously defeated and captured the Emperor Valerian, keeping him prisoner until his death. Shapur had little or no interest in holding on to the territories he conquered; he did, however, borrow their technologies and used their people as labor to build new cities. His legacy is immortalized in rock carvings and inscriptions, especially his victory over Valeria.

Rome tried hard to avenge this bitter defeat but was never able to win a convincing victory over the Sassanids. That empire, which owed much to Shapur I's early leadership and skill, lasted through until the rise of the Muslim caliphate. The fact that Shapur was one of the very few men who humiliated the Romans may represent a positive historical legacy. This reminds the world that no single culture can claim to be superior to all others; in fact, Rome owed a considerable debt to the Sassanids as does the European space. For example, diplomacy and the existence of a Knightly class owes much to Shapur's heirs. In an increasingly inter-dependent world, humanity will benefit most when people learn to value all cultures, to rejoice in the technical achievements of all people, to regard humanity as one family, instead of restricting "human" to those whose image and beliefs mirror their own.

Early years

Shapur was the son of Ardeshir I (r. 226â241), the founder of the Sassanid dynasty and whom Shapur succeeded. His mother was Lady MyrÅd, according to legend was an Arsacid princess.[1]

Shapur accompanied his father's campaigns against the Parthians, whoâat the timeâstill controlled much of the Iranian plateau through a system of vassal states of which the Persian kingdom had itself previously been a part.

Before an assembly of magnates, Ardeshir "judged him the gentlest, wisest, bravest and ablest of all his children"[2] and nominated him as his successor. Shapur also appears as heir apparent in Ardeshir's investiture inscriptions at Naqsh-e Rajab and Firuzabad. The Cologne Mani-Codex indicates that, by 240, Ardeshir and Shapur were already reigning together.[2] In a letter from Gordian III to his senate, dated to 242, the "Persian Kings" are referred to in the plural. Synarchy is also evident in the coins of this period that portray Ardashir facing his youthful son, and which are accompanied by a legend that indicates that Shapur was already referred to as king.

The date of Shapur's coronation remains debated, but 241 is frequently noted.[2] That same year also marks the death of Ardeshir, and earlier in the year, his and Shapur's seizure and subsequent destruction of Hatra, about 100 km southwest of Nineveh and Mosul in present-day Iraq. According to legend, al-Nadirah, the daughter of the king of Hatra, betrayed her city to the Sassanids, who then killed the king and had the city razed. (Legends also have Shapur either marrying al-Nadirah, or having her killed, or both).

War against the Roman Empire

Ardashir I had, towards the end of his reign, renewed the war against the Roman Empire. Shapur I conquered the Mesopotamian fortresses Nisibis and Carrhae and advanced into Syria. Timesitheus, father-in-law of the young emperor, Gordian III, drove him back and defeated him at the Battle of Resaena in 243, regaining Nisibis and Carrhae. Timesitheus died shortly afterward, (244â249), and after his defeat at the Battle of Misiche Gordian himself either died or was killed. Philip the Arab, his successor, then concluded a peace with the Persians in 244. With the Roman Empire debilitated by Germanic invasions and the continuous elevation of new emperors after the death of Trajan Decius (251), Shapur I resumed his attacks.

Shapur conquered Armenia, invaded Syria, and plundered Antioch. Eventually, the Emperor Valerian (253â260) marched against him and by 257, Valerian had recovered Antioch and returned the province of Syria to Roman control. In 259, Valerian moved to Edessa, but an outbreak of plague killed many and weakened the Roman troops defending the city which was then besieged by the Persians. In 260, Valerian arranged a meeting with Shapur to negotiate a peace settlement but was betrayed by Shapur who seized him and held him prisoner for the remainder of his life. Shapur advanced into Asia Minor, but was driven back by defeats at the hands of Balista, who captured the royal harem. Septimius Odenathus, prince of Palmyra, rose in his rear, defeated the Persian army and regained all the territories Shapur had occupied. Shapur was unable to resume the offensive and lost Armenia again.

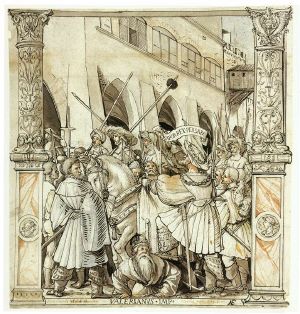

Shapur personally considered one of the great achievements of his reign to be the defeat of the Roman Emperor Valerian. This is presented in a mural at Naqsh-e Rustam, where Shapur is represented on horseback wearing royal armor and crown. Before him kneels Philip the Arab, in Roman dress, asking for grace. In his right hand the king grasps the uplifted arms of what may be Valerian; one of his hands is hidden in his sleeve as the sign of submission. The same scene is repeated in other rock-face inscriptions.

Shapur is said to have publicly shamed Valerian by using the Roman Emperor as a footstool when mounting his horse. Other sources contradict and note that in other stone carvings, Valerian is respected and never on his knees. This is supported by reports that Valerian and some of his army lived in relatively good conditions in the city of Bishapur and that Shapur enrolled the assistance of Roman engineers in his engineering and development plans.

Builder of cities

Shapur I left other reliefs and rock inscriptions. A relief at Naqsh-e Rajab near Istakhr, is accompanied by a Greek translation. Here Shapur I calls himself "the Mazdayasnian (worshiper of Ahuramazda), the divine Sapores, King of Kings of the Aryans, Iranians, and non-Aryans, of divine descent, son of the Mazdayasnian, the divine Artaxerxes, King of Kings of the Aryans, grandson of the divine king Papak." Another long inscription at Istakhr mentions the King's exploits in archery in the presence of his nobles.

From his titles we learn that Shapur I claimed the sovereignty over the whole earth, although in reality his domain extended little farther than that of Ardashir I.

Shapur I built the great town Gundishapur near the old Achaemenid capital Susa, and increased the fertility of the district by a dam and irrigation systemâbuilt by the Roman prisonersâthat redirected part of the Karun River. The barrier is still called Band-e Kaisar, "the mole of the Caesar." He is also responsible for building the city of Bishapur, also built by Roman soldiers captured after the defeat of Valerian in 260.

Interactions with minorities

Shapur is mentioned many times in the Talmud, as King Shabur. He had good relations with the Jewish community and was a friend of Shmuel, one of the most famous of the Babylonian Amoraim.

Under Shapur's reign, the prophet Mani, the founder of Manichaeism, began his preaching in Western Iran, and the King himself seems to have favored his ideas. The Shapurgan, Mani's only treatise in the Middle Persian language, is dedicated to Shapur.

Legacy

Shapur did not appear to want to retain the territories he won. Instead, he carried off treasure and people, putting the latter to work on his building projects. Rock carvings and inscriptions immortalize him, as does his humiliation of Emperor Valerian. He did much to establish the Sassanid's military reputation, so much so that although Rome set out to redeem their honor after Valerian's defeat, their tactics were imitated and it has been said that Romans reserved for the Sassanid Persians alone the status of equals. There was, writes Perowne, only one exception to the rule that "Rome had no equals, no rivals" and that was the Parthians; they were "not barbarians" but highly "civilized."[3] Other defeats followed. Gordian III won a few victories but ended up defeated. Crassus was defeated in 53 B.C.E.; Julius Caesar planned on revenge but died before he had a change to mount an expedition. Hadrian negotiated a peace treaty. Marcus Aurelius Carus had more success but died before he could push home his advantage. The Empire of which Shapur was the second ruler, who did much to shape its future, would resist Rome, surviving longer than the Western Roman Empire. It fell to the Muslims to finally defeat the Sassanids. Shapur I was one of a handful of men who inflicted a defeat on Rome that was never avenged.

The fact that Shapur was one of the very few men who humiliated the Romans may represent a positive historical legacy. This reminds the world that no single civilization can claim to be superior to all others; in fact, Rome owed a considerable debt to the Sassanids; In a modified form, the Roman Imperial autocracy imitated the royal ceremonies of the Sassanid court. These, in turn, had an influence on the ceremonial traditions of the courts of modern Europe. The origin of the formalities of European diplomacy is attributed to the diplomatic relations between the Persian and Roman Empires.[4] In an increasingly inter-dependent world, humanity will benefit most when people learn to value all cultures, to rejoice in the technical achievements of all people and to regard humanity as one family, instead of restricting "human" to those who belong to my nation, race, religion or who identify with my ideology or philosophy or worldview.

Notes

- â Ernst E. Herzfeld, Iran in the Ancient East: Archaeological Studies Presented in the Lowell Lectures at Boston (New York, NY: Hacker Art Books, 1988, ISBN 9780878173082), 287.

- â 2.0 2.1 2.2 Shapur Shahbazi, Shapur I: History Encyclopaedia Iranica, 2002. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- â Stewart Perowne, Hadrian (London, UK: Croom Helm, 1986, ISBN 9780709940487), 127.

- â J.B. Bury, History Of The Later Roman Empire (London, UK: Macmillan, 1923), 109.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bury, J.B. History Of The Later Roman Empire. London, UK: Macmillan, 1923.

- Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). The Encyclopaedia Britannica; A Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, Literature and General Information.. New York, NY: Encyclopaedia Britannica, 1910.

- Herzfeld, Ernst E. Iran in the Ancient East: Archaeological Studies Presented in the Lowell Lectures at Boston. New York, NY: Hacker Art Books, 1988. ISBN 9780878173082.

- Luttwak, Edward. The Grand Strategy of the Roman Empire: From the First Century C.E. to the Third. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979. ISBN 9780801821585.

- Penrose, Jane. Rome and Her Enemies: An Empire Created and Destroyed by War. Oxford, UK: Osprey Pub., 2005. ISBN 9781841769325.

- Perowne, Stewart. Hadrian. London, UK: Croom Helm, 1986. ISBN 9780709940487

- Robinson, B.W., AbÅ« al-QÄsim Ḥasan FirdawsÄ«, and Arthur George Warner. The Persian book of kings: an epitome of the Shahnama of Firdawsi. London, UK: Routledge Curzon, 2002. ISBN 9780700716180.

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

| Sassanid dynasty | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Ardashir I |

"King of kings of Iran and Aniran" 241 â272 |

Succeeded by: Hormizd I |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.