Medici family

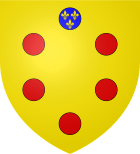

| House of Medici | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Country | Duchy of Florence, Grand Duchy of Tuscany | ||

| Titles |

| ||

| Founder | Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici | ||

| Final ruler | Gian Gastone de' Medici | ||

| Founding year | 1360 | ||

| Dissolution | 1737 | ||

| Ethnicity | Florentine | ||

The Medici family was a powerful and influential Florentine family from the thirteenth to seventeenth century closely associated with the Renaissance and cultural and artistic revival during this period. The family produced three popes (Leo X, Clement VII, and Leo XI), numerous rulers of Florence (notably Lorenzo il Magnifico, to whom Machiavelli dedicated The Prince, and later members of the French and English royal families.

From humble beginnings (the origin of the name is uncertain, it allegedly reflects a medical trade—medico) originating from the agriculture based Mugello region, the family first achieved power through banking. The Medici Bank was one of the most prosperous and most respected in Europe. There are some estimates that the Medici family was for a period of time the wealthiest family in Europe. From this base, the family acquired political power initially in Florence, and later in the wider Italy and Europe. A notable contribution to the profession of accounting was the improvement of the general ledger system through the development of the double-entry bookkeeping system for tracking credits and debits. This system was first used by accountants working for the Medici family in Florence.

Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici was the first Medici to enter banking, and while he became influential in Florentine government, it was not until his son Cosimo the Elder took over in 1434 as gran maestro that the Medici became unofficial heads of state of the Florentine republic. The "senior" branch of the family—those descended from Cosimo the Elder—ruled until the assassination of Alessandro de' Medici, first Duke of Florence, in 1537. This century-long rule was only interrupted on two occasions (between 1494-1512 and 1527-1530), when popular revolts sent the Medici into exile. Power then passed to the "junior" branch—those descended from Lorenzo the Elder, younger son of Giovanni di Bicci, starting with his great-great-grandson Cosimo I the Great. The Medici's rise to power was chronicled in detail by Benedetto Dei (1417-1492). The Medici used their money to gain influence and power. As a family, they shared a passion for the arts and a humanist view of life. While some of their members genuinely, especially Cosimo the Elder, wanted to improve life for the people over whom they exercised power, the dynasty's downfall was an increasing tendency towards despotism.

Art, architecture and science

The most significant accomplishments of the Medici were in the sponsorship of art and architecture, mainly early and High Renaissance art and architecture. Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici, the first patron of the arts in the family, aided Masaccio and ordered the reconstruction of the Church of San Lorenzo. Cosimo the Elder's notable artistic associates were Donatello and Fra Angelico. The most significant addition to the list over the years was Michelangelo, who produced work for a number of Medici, beginning with Lorenzo the Magnificent. In addition to commissions for art and architecture, the Medici were prolific collectors and today their acquisitions form the core of the Uffizi museum in Florence. For seven years Leonardo da Vinci enjoyed Medici patronage.

In architecture, the Medici are responsible for some notable features of Florence; including the Uffizi Gallery, the Pitti Palace, the Boboli Gardens, the Belvedere, and the Palazzo Medici.

Although none of the Medici themselves were scientists, the family is well known to have been the patrons of the famous Galileo, who tutored multiple generations of Medici children, and was an important figurehead for his patron's quest for power. Galileo's patronage was eventually abandoned by Ferdinando II, when the Inquisition accused Galileo of heresy. However, the Medici family did afford the scientist a safe haven for many years. Galileo named the four largest moons of Jupiter after four Medici children he tutored.

- Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici personally commissioned Brunelleschi to reconstruct the Church of San Lorenzo in 1419.

- Eleonora of Toledo, princess of Spain and wife of Cosimo I the Great, purchased Pitti Palace from Buonaccorso Pitti in 1550.

- Cosimo I the Great patronized Vasari who erected the Uffizi Gallery in 1560 and founded the Academy of Design in 1562.

- Marie de Medici, widow of Henri IV and mother of Louis XIII, is used by Peter Paul Rubens in 1622-1623 as the subject in his oil painting Marie de' Medici, Queen of France, Landing in Marseilles.

- Ferdinand II appointed Galileo professor at the University of Pisa (1588).

The Medici have been described as "Godfathers of the Renaissance" due to the important role played by their patronage and sponsorship of art and culture (see Strathern, 2003).

Notable members

- Salvestro de' Medici (1331 – 1388), led the assault against the revolt of the ciompi, became dictator of Florence, and banished in 1382.

- Giovanni di Bicci de' Medici (1360 – 1429), restored the family fortune and made the Medici family the wealthiest in Europe.

- Cosimo de' Medici (Cosimo the Elder) (1389 – 1464), founder of the Medici political dynasty. In addition to patronizing the arts, Cosimo gave a great deal of money to charity and established one of the largest libraries in Europe. He maintained a simple lifestyle, despite his wealth. His son, Piero continued many of his policies and was a popular ruler.

- Lorenzo de' Medici (Lorenzo the Magnificent) (1449 – 1492), leader of Florence during the Golden Age of the Renaissance. Unlike Cosimo and Piero, he was a tyrannical ruler and renowned for his hedonism and lavish lifestyle. Under his rule, the Medici did not enjoy the level of popularity they had earlier enjoyed.

- Pope Leo X (Giovanni de' Medici) (1475 – 1523), a Cardinal-Deacon from the age of 13.

- Pope Clement VII (Giulio de' Medici) (1478 – 1534), also known as Pope Clement VII. It was Pope Clement who excommunicated Henry VIII of England.

- Cosimo I de' Medici (Cosimo I the Great) (1519 – 1574), First Grand Duke of Tuscany who restored the Medici luster, reviving their influence but ruled with little concern for the welfare of his subjects. He built a tunnel, the Vasari Corridor between his palace and the seat of government. This enabled him to move between the two without being accompanied by armed guards, whose presence he would have required if he had walked through the streets of Florence, such was his unpopularity with the people.

- Catherine de' Medici (1519 – 1589), Queen of France.

- Pope Leo XI (Alessandro Ottaviano de' Medici) (1535 – 1605)

- Marie de' Medici (1573 – 1642), Queen and Regent of France who was a harsh opponent of Protestantism in France.

- Anna Maria Luisa de' Medici (1667 – 1743) the last of the Medici line.

What became known as the Popolani line or cadet branch of the family, founded by Cosimo the Elder's brother, Lorenzo, emerged as champions of democracy and of the rights of citizens.

The Medici Popes

The first Medici pope, Leo X, saw the start of the Protestant Reformation under Martin Luther. Using the sale of indulgences to finance his rebuilding of St Peter's basilica, and living a lavish lifestyle, he was a target of Luther's criticism that the church was too worldly. He patronized artists and poets and held recitals and plays at the papal court, where he also loved to give impromptu speeches. In order to commission works by Raphael he designed projects so that the great artist could enjoy his patronage. His sexual exploits were legendary. He appointed his cousin, Giulio as Archbishop of Florence. Leo excommunicated Luther in 1521. The second Medici pope excommunicated Henry VIII of England, thus giving impetus to the English reformation. The third Medici pope, Leo XI was 70 years of age when he was elected to the papacy, and refused to create one of his own relatives a Cardinal, although he dearly loved him, out of a hatred of nepotism. He was a distant member of the Medici family. These Popes are often described as 'humanistic' because they had little genuine interest in spirituality but believed that the classical literature of Greece and Rome contained all that is needed to live a good life. The Medici popes belong to a period when the papacy still exercised considerable political power and ambitious men could further their personal or family interests by achieving this dignity. Nepotism was so ripe that a Medici could be groomed for the papacy from an early age. It is to Leo XI's credit that he refused to engage in this. The Medici popes added considerably to the artistic beauty of the Vatican but did little if anything to guide the Church spiritually at a time when its clergy were being criticized for being too worldly, and the church was under attack for teaching false doctrines, such as that it could sell salvation. In addition to the Medici popes, other members of the family served as Cardinals.

Documentaries

- PBS/Justin Hardy, Medici: Godfathers of the Renaissance Four-hour documentary, covering the rise and fall of the family from Giovanni through the abandonment of Galileo by Ferdinand II. Very watchable and informative, available on DVD & Video. Retrieved February 11, 2008.

- TLC/Peter Spry-Leverton.PSL, The Mummy Detectives: The Crypt Of The Medici One-hour documentary. Italian specialists, joined by mummy expert and TLC presenter Dr. Bob Brier exhume the bodies of Italy's ancient first family and use the latest forensic tools to investigate how they lived and died. Airs on Discovery Channel. Retrieved February 11, 2008.

- BBC Radio 4 3 part series Among the Medici, first episode 22 February 2006, presented by Bettany Hughes Amongst the Medici, bbc.co.uk. Retrieved February 11, 2008.

Further reading

- Dei, Benedetto. La cronica dall’anno 1400 all’anno 1500. edited by Roberto Barducci; preface by Anthony Molho. Florence: F. Papafava, 1985.

- Hibbert, Christopher. The House of Medici: Its Rise and Fall. NY: Morrow, 1975.

- Martines, Lauro. April Blood - Florence and the Plot Against the Medici. NY: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 9780195152951

- Parks, Tim. Medici Money: Banking, Metaphysics, and Art in Fifteenth-Century Florence. NY: W.W. Norton, 2006. ISBN 978-0393328455

- Schevill, Ferdinand. History of Florence: From the Founding of the City Through the Renaissance. NY: Frederick Ungar, 1936.

- Strathern, Paul. The Medici - Godfathers of the Renaissance. London: Jonathan Cape, 2003.

- Vaughan, Herbert M. The Medici Popes. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1908.

- Zophy, Jonathan W. A Short History of Renaissance and Reformation Europe Dances over Fire and Water, 3rd ed. 1996. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2003. ISBN 9780139593628

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2025.

- Outline of the history of the Medici family

- Genealogical manuscript on the house of the Medici

- Genealogical tree of the house of the Medici (Gerrman language)

- Galileo and the Medici Family at PBS

- Medici Archive Project

- the Medici Family at the Galileo Prpject

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.