Indo-Pakistani Wars

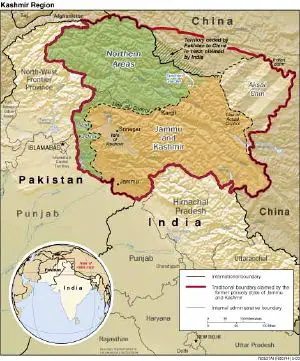

Since the creation of the separate states of India and Pakistan in 1947, the two neighboring nations have engaged in four wars. The first conflict took place soon after independence and is sometimes known as the First Kashmir War. This war was fought between India and Pakistan over the region of Kashmir from October 21, 1947, to December 31, 1948. The second war, in 1965, also concerned the disputed territory of Kashmir. Their third war, in 1971, occurred when India intervened to end the Bangladesh War of Independence, defeating Pakistan. The fourth confrontation, the Kargil conflict of 1999, was again in Kashmir.

Tension between the two nations remains high and both possess nuclear capability, India since 1974 and Pakistan since 1998. The Kashmir issue remains unresolved. Pakistan had been carved from out of India as a homeland for the Sub-Continent's Muslim population, whose leaders claimed that they would be discriminated against if they remained in the Hindu-majority independent India. The "two nation" theory said that Muslims and Hindus represented two distinct and different people who could not live peacefully together.

Since 1948, part of Kashimr (Azad Kasmir) has been under Pakistani control, while the rest is a state within India. However, a large military presence has been maintained, which many regard as an occupation force. Various militant groups engage in violence and the Hindu population of the state has actually decreased. Accusations of brutality have been made against the Indian forces, usually by Muslims, and against Muslim militia, usually by Hindus. Many United Nations resolutions have addressed the conflict, several calling for a referendum by the people of Kashmir to determine their own future. Meanwhile, the conflict seems to be unending and is one of the longest lasting international disputes yet to be resolved (Ganguly 2002). The Line of Control, dividing Indian from Pakistani Kashmir, is patrolled by UN peace-keepers as agreed at Simla in 1971.

The First Indo-Pakistani War

Cause

The state of Jammu and Kashmir was one of a number of Indian states that recognized British paramountcy. Prior to the withdrawal of the British from India, the state came under pressure from both India and Pakistan to join them. The Maharaja of Kashmir, Hari Singh wanted to remain independent and tried to delay the issue. However at the time of British withdrawal the state was invaded by a concentrated force of Pro-Pakistan Tribes from North West Frontier Province (NWFP) and regular Pakistani soldiers. This forced him to accede Kashmir to India, who promptly rushed into Kashmir and thus started the war. The accession is still questioned by the Pakistanis. The Pakistani claim was that since the majority of the Kashmiri population is Muslim, the princely state should have been given to Pakistan. The Indian claim arises from both Maharaja Hari Singh's accession, as had happened with all of the other Indian states, and also that 48 percent of Kashmir was Sikh, Buddhist, and Hindu.

Summary of war

AZK (Azad Kashmir) forces (Azad in Urdu means liberated or free) were the local militia supported by the Pakistanis. The AZK had several advantages in the war, notably:

- Prior to the war, the Jammu and Kashmir state forces had been spread thinly around the border as a response to militant activity, and so were badly deployed to counter a full scale invasion.

- Some of the state forces joined AZK forces.

- The AZK were also aided by regular Pakistani soldiers who manned some of their units, with the proportion increasing throughout the war.

- British officers may have helped the Pakistanis plan the attack. British officers on the scene lead the revolts of the Islamist factions of Kashmir forces, arresting and murdering Dogra officers especially in the Gilgit region. They acted as a backbone for the mass of tribal militias and coordinated their attacks.

As a result of these advantages the main invasion force quickly brushed aside the Jammu and Kashmir state forces. But the attacker’s advantage was not vigorously pressed and the Indians saved the country by airlifting reinforcements. This was at the price of the state formally acceding to India. With Indian reinforcements, the Pakistani/AZK offensive ran out of steam towards the end of 1947. The exception to this was in the High Himalayas sector, where the AZK were able to make substantial progress until turned back at the outskirts of Leh in late June 1948. Throughout 1948, many small-scale battles were fought. None of these gave a strategic advantage to either side and the fronts gradually solidified. Support for the AZK forces by Pakistan became gradually more overt with regular Pakistani units becoming involved. A formal cease-fire was declared on December 31, 1948.

Results of the war

Following the end of the war and the ceasefire, India had managed to acquire two thirds of Kashmir while Pakistan had a third of the region. The Indians retained control of the relatively wealthy and populous Kashmir Valley, and a majority of the population. The number of casualties in the war are estimated at 2,000 for both sides. In 1957, the area became the state of Jammu and Kashmir in the India union. The cease fire line has, over the years, become a de facto division of the state.

Stages of the War

This war has been split into ten stages by time. The individual stages are detailed below.

Initial invasion

A large invasion of the Kashmir valley was mounted by the irregular forces, aimed at Srinagar, the capital of Jammu and Kashmir. The state forces were defeated and the way to the capital, (Srinagar), was open. There was also a mutiny by state forces in favor of the AZK in Domel.

In desperation, Hari Singh, the ruler of Kashmir asked the Indian Government for Indian troops to stop the uprising. The Indians told him that if Singh signed an Instrument of Accession, allowing Kashmir to join the Indian Union, only then would India rush in troops for the protection of one of its territories. This, the Maharaja promptly did. Following this accession, the Indian troops arrived and quickly blocked the advance of the invaders, preventing the imminent sacking of Srinagar. Moreover, many of the irregular forces went home with their loot after plundering local towns and thus failed to press the attack home. In the Punch valley, the Jammu and Kashmir state forces retreated into towns and were besieged.

Indian defense of Kashmir

Indian forces, rapidly airlifted to Srinagar managed to defeat the irregular forces on the outskirts of the town. This was partially due to an outflanking maneuver by armored cars. Shattered, the AZK were pursued as far as Baramula and Uri and these towns were recaptured. In the Punch valley the sieges of the loyal Jammu and Kashmir state forces continued. Meanwhile, the troops in Gilgit (the Gilgit Scouts) mutinied and this yielded most of the far north of the state to the AZK. They were joined by the Forces of Chitral State, the Mehtar of Chitral had acceded to Pakistan and he sent his forces to fight alongside the Gilgitis because of the close cultural and historical ties between Chitral and Gilgit.

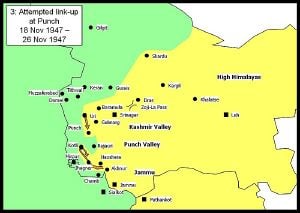

Attempted link-up at Punch

The Indian forces ceased their pursuit of the shattered AZK forces and swung south in an attempt to relieve Punch. This was less successful than hoped, because inadequate reconnaissance had underestimated the difficulty of the roads. Although the relief column eventually reached Punch, the siege could not be lifted. A second relief column reached only Kotli and was forced to evacuate its garrison. Mirpur was captured by the AZK and its inhabitants, particularly the Hindus, were slaughtered.

Fall of Jhanger

The Pakistani/AZK forces attacked and captured Jhanger. They then attacked Naoshera successfully. Other Pakistani/AZK forces made a series of unsuccessful attacks on Uri. In the south, a minor Indian attack secured Chamb. By this stage of the war, the front line began to stabilize as more Indian troops became available.

Op Vijay

The Indian forces launched a counterattack in the south, recapturing Jhanger and Rajauri. In the Kashmir Valley the Pakistani/AZK forces continued attacking the Uri garrison. In the north, Skardu was besieged by Pakistani/AZK forces.

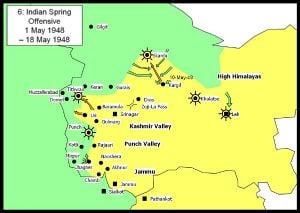

Indian spring offensive

The Indians held onto Jhanger despite numerous counterattacks from the AZK, who were increasingly supported by regular Pakistani Forces. In the Kashmir Valley, the Indians attacked, recapturing Tithwail. The AZK made good progress in the High Himalayas sector, infiltrating troops to bring Leh under siege, capturing Kargil and defeating a relief column heading for Skardu.

Operations Gulab & Erase

The Indians continued to attack in the Kashmir Valley sector, driving north to capture Keran and Gurais. They also repelled a counterattack aimed at Tithwail. The forces besieged in Punch broke out and temporarily linked up with the outside world again. The Kashmir State army was able to defend Skardu from the Gilgit Scouts and thus, they were not able to proceed down the Indus valley towards Leh. In August the Chitral Forces under Mata-ul-Mulk besieged Skardu and with the help of artillery were able to take the city. This freed the Gilgit Scouts to push further into Ladakh.

Operation Duck

During this time the front began to settle down with less activity on both sides The only major event was an unsuccessful attack by the Indians towards Dras (Operation Duck). The siege of Punch continued.

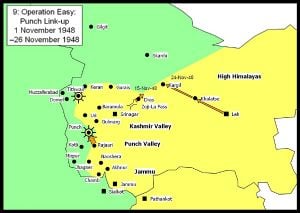

Operation Easy

The Indians began gaining the upper hand in all sectors. Punch was finally relieved after a siege of over a year. The Gilgit forces in the High Himalayas, who had initially made good progress, were finally defeated. The Indians pursued as far as Kargil, before being forced to halt due to supply problems. The Zoji-La pass was forced by using tanks (which had not been thought possible at that altitude) and Dras was recaptured. The use of tanks was based on experience gained in Burma in 1945.

Moves up to cease-fire

Realizing that they were not going to make any further progress in any sector, the Pakistanis decided to end the war. A UN cease-fire was arranged for the December 31, 1948. A few days before the cease-fire, the Pakistanis launched a counter attack, which cut the road between Uri and Punch. After protracted negotiations, a cease-fire was agreed to by both countries, which came into effect, as laid out in the UNCIP resolution[1] of August 13, 1948 were adopted by the UN on January 5, 1949. This required Pakistan to withdraw its forces, both regular and irregular, while allowing India to maintain minimum strength of its forces in the state to preserve law and order. On compliance of these conditions a plebiscite was to be held to determine the future of the territory. In all, 1,500 soldiers died on each side during the war[2] and Pakistan was able to acquire roughly two-fifths of Kashmir while India acquired the majority, including the most populous and fertile regions.

Military insights gained from the war.

On the use of armor

The use of light tanks and armored cars was important during two stages of the war. Both of these Indian victories involved very small numbers of AFVs. These were:

- The defeat of the initial thrust at Srinagar, which was aided by the arrival of 2 armored cars in the rear of the irregular forces.

- The forcing of the Zoji-La pass with 11 Stuart M5 light tanks.

This may show that armor can have a significant psychological impact if it turns up at places thought of as impossible. It is also likely that the invaders did not deploy anti-tank weapons to counter these threats. Even the lightest weapons will significantly encumber leg infantry units, so they may well have been perceived as not worth the effort of carrying about, and left in rear areas. This would greatly enhance the psychological impact of the armor when it appeared. The successful use of armor in this campaign strongly influenced Indian tactics in the 1962 war, where great efforts were made to deploy armor to inhospitable regions (although with much less success in that case).

Progression of front lines

It is interesting to chart the progress of the front lines. After a certain troop density was reached, progress was very slow with victories being counted in the capture of individual villages or peaks. Where troop density was lower (as it was in the High Himalayas sector and at the start of the war) rates of advance were very high.

Deployment of forces

- The Jammu and Kashmir state forces were spread out in small packets along the frontier to deal with militant incidents. This made them very vulnerable to a conventional attack. India used this tactic successfully against the Pakistan Army in East Pakistan (present day Bangladesh) in the 1971 war.

Indo-Pakistani War of 1965

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1965, also known as the Second Kashmir War, was the culmination of a series of skirmishes that occurred between April 1965 and September 1965, between India and Pakistan. The war was the second fought between India and Pakistan over the region of Kashmir. The war lasted five weeks, resulted in thousands of casualties on both sides and ended in a United Nations (UN) mandated ceasefire. It is generally accepted that the war began following the failure of Pakistan's "Operation Gibraltar" which was designed to infiltrate and invade Jammu and Kashmir.

Much of the war was fought by the countries' land forces in the region of Kashmir and along the International Border (IB) between India and Pakistan. The war also involved a limited participation from the countries' respective air forces. This war saw the largest amassing of troops in Kashmir, a number that was overshadowed only during the 2001-2002 military standoff between India and Pakistan, during which over a million troops were placed in combat positions in the region. Many details of this war, like those of most Indo-Pakistani Wars, remain unclear and riddled with media biases.

Pre-war escalation

Fighting broke out between India and Pakistan in an area known as the Rann of Kutch, a barren region in the Indian state of Gujarat. Initially involving the border police from both nations, the disputed area soon witnessed intermittent skirmishes between the countries' armed forces, first on March 20 and again in April 1965. In June the same year, British Prime Minister Harold Wilson successfully persuaded both countries to end hostilities and set up a tribunal to resolve the dispute. The verdict which came later in 1968, saw Pakistan gaining only 350 square miles (900 km²) of the Rann of Kutch out of its original claim of 3500 sq miles.[3]

After its successes in the Rann of Kutch, Pakistan, under the leadership of General Ayub Khan is said to have believed that the Indian Army was unable to defend itself against a quick military campaign in the disputed territory of Kashmir, following a loss to China in 1962.[4] Pakistan believed that the population of Kashmir was generally discontented with Indian rule and that a resistance movement could be ignited by a few infiltrating saboteurs. This was codenamed Operation Gibraltar.[5] For its part, Pakistan claimed to have been concerned by the attempts of India to absorb Kashmir‚ÄĒa state that Pakistan claims as "disputed," into the Indian union by way of Articles 356 and 357 of the Indian Constitution allowing the President of India to declare President's Rule in the disputed state. Pakistan was taken aback by the lack of military and moral support by the United States, an ally with whom the country had signed an Agreement of Cooperation. The United States refused to come to Pakistan's aid and declared its neutrality in the war by cutting off military supplies to both sides.

The war

On August 15, 1965, Indian forces crossed the ceasefire line and launched an attack on Pakistan administered Kashmir, marking an official beginning to the war. Most of the war was fought on land by each country's infantry and armored units, with substantial backing from their air forces. Initially, the Indian Army met with considerable success in the northern sector (Kashmir). After launching a prolonged artillery barrage against Pakistan, India was able to capture three important mountain positions. However, by the end of the month both sides were on even footing, as Pakistan had made progress in areas such as Tithwal, Uri, and Punch and India had gains in Pakistan Administered Kashmir (Azad Kashmir, Pakistan Occupied Kashmir), having captured the Haji Pir Pass eight kilometers inside Pakistani territory.

These territorial gains and rapid Indian advances were met with a counterattack by Pakistan in the southern sector (Punjab) where Indian forces, having been caught unprepared, faced technically superior Pakistani tanks and suffered heavy losses. India then called in its air force to target the Pakistani attack in the southern sector. The next day, Pakistan retaliated, initializing its own air force to retaliate against Indian forces and air bases in both Kashmir and Punjab. India crossed the International Border (IB) on the Western front on September 6 (some officially claim this to be the beginning of the war). On September 6, the 15th Infantry Division of the Indian Army, under World War II veteran Major General Prasad battled a massive counterattack by Pakistan near the west bank of the Ichhogil Canal (BRB Canal), which was a de facto border of India and Pakistan. The General's entourage itself was ambushed and he was forced to flee his vehicle. A second, this time successful, attempt to cross over the Ichhogil Canal was made through the bridge in the village of Barki, just east of Lahore. This brought the Indian Army within range of Lahore International Airport, and as result the United States requested a temporary ceasefire to allow it to evacuate its citizens in Lahore.

The same day, a counter offensive consisting of an armored division and infantry division supported by Pakistan Air Force Sabres rained down on the Indian 15th Division forcing it to withdraw to its starting point. On the days following September 9, both nations' premiere formations were routed in unequal battles. India's 1st Armored Division, labeled the "pride of the Indian Army," launched an offensive towards Sialkot. The Division divided itself into two prongs and came under heavy Pakistani tank fire at Taroah and was forced to withdraw. Similarly, Pakistan's pride, the 1st Armored Division, pushed an offensive towards Khemkaran with the intent to capture Amritsar (a major city in Punjab, India) and the bridge on River Beas to Jalandhar. The Pakistani 1st Armored Division never made it past Khem Karan and by the end of September 10 lay disintegrated under the defenses of the Indian 4th Mountain Division at what is now known as the Battle of Asal Uttar (Real Answer). The area became known as Patton Nagar (Patton Town) as Pakistan lost/abandoned nearly 100 tanks, mostly Patton tanks obtained from the United States.

The war was heading for a stalemate, with both nations holding territory of the other. The Indian army suffered 3,000 battlefield deaths, while Pakistan suffered 3,800. The Indian army was in possession of 710 mile² (1,840 km²) of Pakistani territory and the Pakistan army held 210 mile² (545 km²) of Indian territory, mostly in Chumb, in the northern sector.

The navies of both India and Pakistan played no prominent role in the war of 1965. On September 7, a flotilla of the Pakistani Navy carried out a bombardment of the coastal Indian town and radar station of Dwarka under the name of Operation Dwarka, which was 200 miles (300 km) south of the Pakistani port of Karachi. There was no immediate retaliatory response from India. Later, the Indian fleet from Bombay sailed to Dwarka to patrol off that area to deter further bombardment.

According to Pakistani sources, one maiden submarine, PNS Ghazi kept the Indian Navy's aircraft carrier besieged in Bombay throughout the war. Indian sources claim that it was not their intention to get into a naval conflict with Pakistan, but to restrict the war to a land-based conflict.

Further south, towards Bombay, there were reports of underwater attacks by the Indian Navy against what they suspected were American-supplied Pakistani submarines, but this was never confirmed.

Covert operations

There were a couple of covert operations launched by the Pakistan Army to infiltrate Indian airbases and sabotage them. The SSG (Special Services Group) commandos were parachuted into enemy territory and, according to the then Chief of Army Staff General Musa Khan, more than 180 commandos penetrated the enemy territory for this purpose. Indian sources, however, claim as many as 800-900 commandos were airdropped, though that figure is probably for the duration of whole war. Given that most of the Indian targets (Halwara, Pathankot and Adampur) were deep into enemy territory only 11-15 commandos made it back alive and the stealth operation proved ineffective. Of those remaining, 136 were taken prisoner and 22 were killed in encounters with the army, police, or civilians. The daring attempt proved to be a disaster with the commander of the operations, Major Khalid Butt also being arrested.

Losses

India and Pakistan hold widely divergent claims on the damage they have inflicted on each other and the amount of damage suffered by them. The following summarizes each nation's claims.

| Indian claims | Pakistani claims[5] | Independent sources[4] | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Casualties | - | - | 3000 Indian soldiers, 3800 Pakistani soldiers |

| Aircraft destroyed | 35 IAF, 73 PAF | 19 PAF, 104 IAF | 20 PAF aircraft |

| Aerial victories | 13 | 30 | - |

| Tanks destroyed | 128 Indian tanks, 300-350 Pakistani tanks | 165 Pakistan tank, ?? Indian tanks | 200 Pakistani tanks |

| Land area won | 1,500 mi2 (2,400 km2) of Pakistani territory | 2,000 mi² (3,000 km²) of Indian territory | India held 710 mi² (1,840 km²) of Pakistani territory and Pakistan held 210 mi² (545 km²) of Indian territory |

There have been only a few neutral assessments of the damages of the war. In the opinion of GlobalSecurity.org, "The losses were relatively heavy‚ÄĒon the Pakistani side, twenty aircraft, 200 tanks, and 3,800 troops. Pakistan's army had been able to withstand Indian pressure, but a continuation of the fighting would only have led to further losses and ultimate defeat for Pakistan."

Ceasefire

On September 22, the United Nations Security Council unanimously passed a resolution that called for an unconditional ceasefire from both nations. The war ended the following day. The Soviet Union, led by Premier Alexey Kosygin, brokered a ceasefire in Tashkent (now in Uzbekistan), where Indian Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri and Pakistani President Ayub Khan signed an agreement to withdraw to pre-August lines no later than February 25, 1966. The war remained largely inconclusive despite Pakistan suffering relatively more losses, and saw a six year period of relative peace between the two neighboring rivals before war broke out once again in 1971.

Intelligence failures

Indian miscalculations

Strategic miscalculations by both nations ensured that the result of this war remained a stalemate. The Indian Army failed to recognize the presence of heavy Pakistani artillery and armaments in Chumb and suffered significant losses as a result. The "Official History of the 1965 War," drafted by the Ministry of Defence of India in 1992, was a long suppressed document that outlined intelligence and strategic blunders by India during the war. According to the document, on September 22, when the Security Council was pressing for a ceasefire, the Indian Prime Minister asked the commanding Gen. Chaudhuri if India could possibly win the war, were he to hold off accepting the ceasefire for a while longer. The general replied that most of India's front line ammunition had been used up and the Indian Army had suffered considerable tank loss.

It was found later that only 14 percent of India's front line ammunition had been fired and India still held twice the number of tanks than Pakistan did. By this time, the Pakistani Army itself had used close to 80 percent of its ammunition. Air Chief Marshal (retd) P.C. Lal, who was the Vice Chief of Air Staff during the conflict, points to the lack of coordination between the IAF and the Indian army. Neither side revealed its battle plans to the other.The battle plans drafted by the Ministry of Defence and General Chaudhari, did not specify a role for the Indian Air Force in the order of battle. This attitude of Gen. Chaudhari was referred to by ACM Lal as the "Supremo Syndrome," a patronizing attitude sometimes attributed to the Indian army towards the other branches of the Indian Military.

Pakistani miscalculations

The Pakistani Army's failures started from the drawing board itself, with the supposition that a generally discontent Kashmiri people would rise to the occasion and revolt against their Indian rulers, bringing about a swift and decisive surrender of Kashmir. For whatever reason, the Kashmiri people did not revolt, and on the contrary, provided the Indian Army with enough information for them to learn of "Operation Gibraltar" and the fact that the Army was battling not insurgents, as they had initially supposed, but Pakistani Army regulars. The Pakistani army failed to recognize that the Indian policy makers would attack the southern sector and open up the theater of conflict. Pakistan was forced to dedicate troops to the southern sector to protect Sialkot and Lahore instead of penetrating into Kashmir.

"Operation Grand Slam," which was launched by Pakistan to capture Akhnur, a town north-east of Jammu and a key region for communications between Kashmir and the rest of India, was also a failure. Many Pakistani critics have criticized the Ayub Khan administration for being indecisive during Operation Grand Slam. They claim that the operation failed because Ayub Khan knew the importance of Akhnur to India (having called it India's "jugular vein") and did not want to capture it and drive the two nations into an all out war. Despite progress made in Akhnur, General Ayub Khan for some inexplicable reason relieved the commanding Major General Akhtar Hussain Malik of charge and replaced him with Gen. Yahya Khan. A 24 hour lull ensued, which allowed the Indian army to regroup in Akhnur and oppose a lackluster attack headed by General Yahya Khan. "The enemy came to our rescue," asserted the Indian Chief of Staff of the Western Command. Many authors like Stephen Philip Cohen, have consistently viewed that Pakistan Army "acquired an exaggerated view of the weakness of both India and the Indian military … the 1965 war was a shock." As a result most of the blame was heaped on the leadership and little importance given to intelligence failures that persisted until the debacle of the 1971 war, when Pakistan was comprehensively defeated and dismembered by India, leading to the creation of Bangladesh.

Consequences of the war

The war created a tense state of affairs in its aftermath. Though the war was indecisive, Pakistan suffered much heavier material and personnel casualties than India. Many war historians believe that had the war continued, with growing losses and decreasing supplies, Pakistan would have been eventually defeated. India's decision to declare ceasefire with Pakistan caused some outrage among the Indian populace, who believed they had the upper hand. Both India and Pakistan increased their defense spending and Cold War politics had taken root in the subcontinent. Partly as a result of the inefficient information gathering, India established the Research and Analysis Wing for external espionage and intelligence. India slowly started aligning with the Soviet Union both politically and militarily. This would be cemented formally years later, before the Bangladesh Liberation War. In light of the previous war against the Chinese, the performance in this war was viewed as a "politico-strategic" victory in India.

Many Pakistanis, rated the performance of their military positively. September 6 is celebrated as Defense Day in Pakistan, commemorating the successful defense of Sailkot against the Indian army. The Pakistani Air Force's performance was seen in much better light compared to that of the Pakistani navy and army. However, the end game left a lot to desire, as Pakistan had lost more ground than gained and more importantly did not achieve the goal of occupying Kashmir, which has been viewed by many impartial sources as a defeat for Pakistan.[6] Many high ranking Pakistani officials and military experts later criticized the faulty planning during Operation Gibraltar that ultimately led to the war. The Tashkent declaration was further seen as a raw deal in Pakistan, though few citizens realized the gravity of the situation that existed at the end of the war. Under the advice of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, Pakistan's then foreign minister, Ayub Khan had raised very high expectations among the people of Pakistan about the superiority‚ÄĒif not invincibility‚ÄĒof its armed forces.[7] But Pakistan's inability to attain its military aims during the war created a political liability for Ayub. The defeat of its Kashmiri ambitions in the war led to the army's invincibility being challenged by an increasingly vocal opposition.[8] And with the war creating a huge financial burden, Pakistan's economy, which had witnessed rapid progress in the early 60s, took a severe beating.

Another negative consequence of the war was the growing resentment against the Pakistani government in East Pakistan. Bengali leaders accused the government for not providing adequate security for East Pakistan, even though large sums of money were taken from the east to finance the war. Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was apprehensive of this situation and the need for greater autonomy for the east led to another war between India and Pakistan in 1971.

Indo-Pakistani War of 1971

The Indo-Pakistani War of 1971 was a major military conflict between India and Pakistan. The war is closely associated with the Bangladesh Liberation War (sometimes also referred to as Pakistani Civil War). There is an argument about exact dates of the war. However, the armed conflict on India's western front during the period between December 3, 1971 and December 16, 1971 is called the Indo-Pakistani War by both the Bangladeshi and Indian armies. The war ended in a crushing defeat for Pakistani military in just a fortnight.

Background

The Indo-Pakistani conflict was sparked by the Bangladesh Liberation War, a conflict between the traditionally dominant West Pakistanis and the majority East Pakistanis. The war ignited after the 1970 Pakistani election, in which the East Pakistani Awami League won 167 of 169 seats in East Pakistan, thus securing a simple majority in the 313-seat lower house of the Pakistani parliament. Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman presented Six Points and claimed the right to form the government. After the leader of the Pakistan People's Party, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, refused to give premiership of Pakistan to Mujibur, President Yahya Khan called in the military, which was made up largely of West Pakistanis.

Mass arrests of dissidents began, and attempts were made to disarm East Pakistani soldiers and police. After several days of strikes and non-cooperation movements, Pakistani military cracked down on Dhaka on the night of March 25, 1971. The Awami League was banished, and many members fled into exile in India. Mujib was arrested and taken to West Pakistan.

On March 27, 1971, Ziaur Rahman, a rebellious major in the Pakistani army, declared the independence of Bangladesh on behalf of Mujibur. In April, exiled Awami League leaders formed a government-in-exile in Boiddonathtola of Meherpur. The East Pakistan Rifles, an elite paramilitary force, defected to the rebellion. A guerrilla troop of civilians, the Mukti Bahini, was formed to help the Bangladesh Army.

India's involvement in Bangladesh Liberation War

On March 27, 1971, the Prime Minister of India, Indira Gandhi, expressed full support of her government to the Bangladeshi struggle for freedom. The Bangladesh-India border was opened to allow the tortured and panic-stricken Bangladeshis safe shelter in India. The governments of West Bengal, Bihar, Assam, Meghalaya, and Tripura established refugee camps along the border. Exiled Bangladeshi army officers and voluntary workers from India immediately started using these camps for the recruitment and training of Mukti Bahini guerrillas.

As the massacres in East Pakistan escalated, an estimated 10 million refugees fled to India, causing financial hardship and instability in the country. The United States, a long and close ally of Pakistan, continued to ship arms and supplies to West Pakistan.

Indira Gandhi launched a diplomatic offensive in the early fall of 1971 touring Europe, and was successful in getting both the United Kingdom and France to break with the United States, and block any pro-Pakistan directives in the United Nations security council. Gandhi's greatest coup was on August 9, when she signed a twenty-year treaty of friendship and co-operation with the Soviet Union, greatly shocking the United States, and providing India with insurance that the People's Republic of China would not be involved in the conflict. China, an ally of Pakistan, had been providing moral support, but little military aid, and did not advance troops to its border with India.

Operation of the Mukti Bahini caused severe casualties to the Pakistani Army, which was in control of all district headquarters. As the flow of refugees swelled to a tide, the economic costs for India began to escalate. India began providing support, including weapons and training, for the Mukti Bahini, and began shelling military targets in East Pakistan.

India's official engagement with Pakistan

By November, war seemed inevitable; a massive buildup of Indian forces on the border with East Pakistan had begun. The Indian military waited for winter, when the drier ground would make for easier operations and Himalayan passes would be closed by snow, preventing any Chinese intervention. On November 23, Yahya Khan declared a state of emergency in all of Pakistan and told his people to prepare for war.

On the evening of Sunday, December 3, the Pakistani air force launched sorties on eight airfields in north-western India. This attack was inspired by the Arab-Israeli Six Day War and the success of the Israeli preemptive strike. However, the Indians had anticipated such a move and the raid was not successful. The Indian Air Force launched a counter-attack and quickly achieved air superiority. On the Eastern front, the Indian Army joined forces with the Mukti Bahini to form the Mitro Bahini (Allied Forces); the next day, Indian forces responded with a massive coordinated air, sea, and land assault on East Pakistan.

Yahya Khan counter-attacked India in the West, in an attempt to capture land which might have been used to bargain for territory they expected to lose in the east. The land battle in the West was crucial for any hope of preserving a united Pakistan. The Indian Army quickly responded to the Pakistan Army's movements in the west and made some initial gains, including capturing around 5,500 sq miles of Pakistan territory (land gained by India in Pakistani Kashmir and the Pakistani Punjab sector were later ceded in the Shimla Agreement of 1972, as a gesture of goodwill). The Indian Army described its activities in East Pakistan as:

The Indian Army merely provided the coup de grace to what the people of Bangladesh had commenced‚ÄĒactive resistance to the Pakistani Government and its Armed Forces on their soil.

At sea, the Indian Navy proved its superiority by the success of Operation Trident, the name given to the attack on Karachi's port. It also resulted in the destruction of two destroyers and one minesweeper, and was followed by the successful Operation Python. The waters in the east were also secured by the Indian Navy. The Indian Air Force conducted 4,000 sorties in the west while its counterpart, the PAF put up little retaliation, partly because of the paucity of non-Bengali technical personnel. This lack of retaliation has also been attributed to the deliberate decision of the PAF High Command to cut its losses, as it had already incurred huge casualties in the conflict. In the east, the small air contingent of Pakistan Air Force No. 14 Sqn was destroyed achieving air superiority in the east. Faced with insurmountable losses, the Pakistani military capitulated in just under a fortnight. On December 16, the Pakistani forces in East Pakistan surrendered. The next day India announced a unilateral ceasefire, to which Pakistan agreed.

American involvement

The United States supported Pakistan both politically and materially. President Richard Nixon denied getting involved in the situation, saying that it was an internal matter of Pakistan.

Several documents released from the Nixon Presidential Archives[9] show the extent of the tilt that the Nixon Administration demonstrated in favor of Pakistan. Among them, the infamous Blood telegram from the U.S. embassy in Dacca, East Pakistan, stated the horrors of genocide taking place. Nixon, backed by Henry Kissinger, is alleged to have wanted to protect the interests of Pakistan, as he was apprehensive of India. Archer Blood was promptly transferred out of Dacca. As revealed in the declassified transcripts released by the State Department, President Nixon was using the Pakistanis to normalize relations with China. This would have three important effects: Opening rifts between the Soviet Union, China, and North Vietnam, opening the potentially huge Chinese market to American business and creating a foreign policy coup in time to win the 1972 Presidential Elections. Since Nixon believed the existence of Pakistan to be critical to the success of his term, he went to great lengths to protect his ally. In direct violation of the Congress-imposed sanctions on Pakistan, Nixon sent military supplies to Pakistan and routed them through Jordan and the Shah-ruled Iran.[10]

U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations George H. W. Bush branded the Indian action as "aggression" at the time and took up the matter in the UN Security Council. The United States believed that should Pakistan's armed forces in the east collapse, India would transfer its forces from there to attack West Pakistan, which was an ally in the Central Treaty Organization. This was confirmed in official British secret transcripts declassified in 2003.[11] Nixon also showed a bias towards Pakistan despite widespread condemnation of the dictatorship even amongst his administration, as Oval Office records show. Kissinger wanted China to attack India for this purpose.

When Pakistan's defeat seemed certain, Nixon sent the USS Enterprise to the Bay of Bengal from the Gulf of Tonkin. Enterprise arrived on station on December 11, 1971. Originally, the deployment of Enterprise was claimed to be for evacuating U.S. citizens and personnel from the area. Later, Nixon claimed that it was also as a gesture of goodwill towards Pakistan and China. Enterprise's presence was considered an intimidation, and hotly protested by India and the Soviet Union. The Soviet Union called this U.S. move one of Gunboat Diplomacy.[12] On December 6, and December 13, the Soviet Navy dispatched two groups of ships, armed with nuclear missiles, from Vladivostok; they trailed U.S. Task Force 74 in the Indian Ocean from December 18 until January 7, 1972.

Effects

The war led to the immediate surrender of Pakistani forces to the Indian Army. Bangladesh became an independent nation, and the third most populous Muslim country. Loss of East Pakistan demoralized the Pakistani military and Yahya Khan resigned, to be replaced by Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. Mujibur Rahman was released from West Pakistani prison and returned to Dhaka on January 10, 1972.

The exact cost of the violence on the people of East Pakistan is not known. R.J. Rummel cites estimates ranging from one to three million people killed.[13] Other estimates place the death toll lower, at 300,000.

On the brink of defeat around December 14, the Pakistani Army and its local collaborators systematically killed a large number of Bengali doctors, teachers, and intellectuals, part of a pogrom against the Hindu minorities who constituted the majority of urban educated intellectuals. Young men, who were seen as possible rebels, were also targeted, especially students.

The cost of the war for Pakistan in monetary and human resources was high. In the book Can Pakistan Survive? Pakistan based author Tariq Ali writes, "Pakistan lost half its navy, a quarter of its air force and a third of its army." India took 93,000 prisoners of war that included Pakistani soldiers as well as some of their East Pakistani collaborators. It was one of the largest surrenders since World War II. India originally wished to try them for war crimes for the brutality in East Pakistan, but eventually acceded to releasing them as a gesture of reconciliation. The Simla Agreement, created the following year, also saw most of Pakistani territory (more than 13,000 km²) being given back to Pakistan to create "lasting peace" between the two nations.

Important dates

- March 7, 1971: Sheikh Mujibur Rahman declares that, "The current struggle is a struggle for independence," in a public meeting attended by almost a million people in Dhaka.

- March 25, 1971: Pakistani forces start Operation Searchlight, a systematic plan to eliminate any resistance. Thousands of people are killed in student dormitories and police barracks in Dhaka.

- March 26, 1971: Major Ziaur Rahman declares independence from Kalurghat Radio Station, Chittagong. The message is relayed to the world by Indian radio stations.

- April 17, 1971: Exiled leaders of Awami League form a provisional government.

- December 3, 1971: War between India and Pakistan officially begins when West Pakistan launches a series of preemptive airstrikes on Indian airfields.

- December 14, 1971: Systematic elimination of Bengali intellectuals is started by Pakistani Army and local collaborators.

- December 16, 1971: Lieutenant-General A. A. K. Niazi, supreme commander of Pakistani Army in East Pakistan, surrender to the Allied Forces (Mitro Bahini) represented by Lieutenant General Aurora of the Indian Army at the surrender. Bangladesh gains independence.

Notes

- ‚ÜĎ Resolution adopted by the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan on 13 August 1948. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Indo-Pakistani Conflict of 1947-48 Global Security. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Bharat Bhushan, "Tulbul, Sir Creek and Siachen: Competitive Methodologies," South Asian Journal (2005).

- ‚ÜĎ 4.0 4.1 Indo-Pakistan War of 1965 Global Security. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ 5.0 5.1 Agha Humayun Amin, "Grand Slam‚ÄĒA Battle of Lost Opportunities". Defence Journal. Sept 2000. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ U.S. Relations With Pakistan U.S. Department of State. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Dr Ahmad Faruqui, Remember 6th of September 1965.

- ‚ÜĎ Mahmud Ali, The Rise of Pakistan's Army BBC News (December 24, 2003). Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ The Tilt: The U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971 The National Security Archive. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Stephen R. Shalom, The Men Behind Yahya in the Indo-Pak War of 1971. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Rick Fountain, Bangladesh war secrets revealed BBC (January 1, 2003). Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Clarence Earl Carter, The Indian Navy: A Military Power at a Political Crossroads. Retrieved July 27, 2023.

- ‚ÜĎ Rudolph J. Rummel, Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder since 1900 (LIT Verlag, 1998, ISBN 978-3825840105).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brines, Russell. The Indo-Pakistan Conflict. London: Pall Mall Press, 1968 ISBN 0269162321

- Cohen, Lt Col Maurice. Thunder over Kashmir. Hyderabad: Orient Longman Ltd, 1955.

- Fricker, John. Battle for Pakistan. London: I Allan, 1979. ISBN 0711009295

- Ganguly, Sumit. Conflict Unending: India-Pakistani Tensions Since 1947. NY: Columbia University Press, 2002; New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2001. ISBN 0231123698

- Hanhimaki, Jussi. The Flawed Architect: Henry Kissinger and American Foreign Policy. NY: Oxford University Press, 2004. ISBN 0195172213

- Hinds, Brig Gen S. R. Battle of Zoji La. New Delhi: Military Digest, 1962.

- Indian Ministry of Defence. ‚ÄúOperations In Jammu and Kashmir 1947-1948.‚ÄĚ Thomson Press (India) Limited. New Delhi 1987.

- Mohan, P. V. S. Jagan and Samir Chopra, The India-Pakistan Air War of 1965. New Delhi: Manohar Publishers, 2005. ISBN 8173046417

- Musa, Muhammad. My Version: India-Pakistan War 1965. Lahore: Wajidalis, 1983.

- Niazi, Amir Abdullah Khan. Betrayal of East Pakistan. New Delhi: Manohar, 1998. ISBN 817304256X

- Palit, D. K. The Lightning Campaign: The Indo-Pakistan War 1971. Compton Press Ltd, 1972. ISBN 0900193107

- Praval, K. C. The Indian Army After Independence. New Delhi: Lancer International, 1993. ISBN 189829450

- Rummel, Rudolph J. Statistics of Democide: Genocide and Mass Murder since 1900. LIT Verlag, 1998. ISBN 978-3825840105

- Rushdie, Salman. Shalimar the Clown. NY: Random House, 2006. ISBN 0679783482

- Saigal, J. R. Pakistan Splits: The Birth of Bangladesh. New Delhi: Manas Publications, 2004. ISBN 817049124X

- Sandu, Maj Gen Gurcharn. The Indian Armour: History Of The Indian Armoured Corps 1941-1971. New Delhi: Vision Books Private Limited, 1987. ISBN 8170940044

- Sen, Maj Gen L. P. Slender Was The Thread: The Kashmir Confrontation 1947-1948. New Delhi: Orient Longmans Ltd, 1969.

- Singh, Maj K. Barhma. History of Jammu and Kashmir Rifles (1820-1956). New Delhi: Lancer International, 1990. ISBN 8170620910

- Vasm, Lt Gen E. A. Without Baggage: A Personal Account of the Jammu and Kashmir Operations 1947-1949. Dehradun: Natraj Publishers, 1987. ISBN 8185019096

External links

All links retrieved November 28, 2024.

- Indo-Pakistan War 1965. GlobalSecurity.org

- The India-Pakistan War, 1965: 40 Years On Rediff.com.

- Spirit of ’65 & the parallels with today by Ayaz Amir.

- Pakistan intensifies air raid on India BBC.

- The Tilt: The U.S. and the South Asian Crisis of 1971 The National Security Archive.

- Dec 16, 1971: any lessons learned? by Ayaz Amir.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.