Dinka

The Dinka are a group of tribes of south Sudan, inhabiting the swamplands of the Bahr el Ghazal region of the Nile basin, Jonglei and parts of southern Kordufan and Upper Nile regions. They are mainly agro-pastoral people, semi-nomadic, relying on cattle herding at riverside camps in the dry season and growing millet (Anyanjang) in fixed settlements during the rainy season. They number around 4.5 million people, constituting about 12 percent of the population of the entire country. They constitute the largest ethnic group in South Sudan.

As a result of the civil wars in Sudan following its independence from Great Britain, Dinka have been involved in political strife, armed rebellion, and forced to feel their homeland as refugees. As a result, Dinka populations now exist far from their homeland. The majority of Dinka, however, continue to live in Southern Sudan, maintaining much of the traditional ways they have followed for generation upon generation, combined with the introduction of some modern ways.

Introduction

Dinka, or as they refer to themselves, Mounyjaang, are one of the branches of the River Lake Nilotes (mainly agro-pastoral peoples of East Africa who speak Nilotic languages, including the Nuer and Maasai). The Dinka language ‚ÄĒ also called Dinka as well as "thu…ĒŇčj√§Ňč (thuongjang)" ‚ÄĒ is one of the Nilotic family of languages, belonging to the Chari-Nile branch of the Nilo-Saharan family. It is written using the Latin alphabet with a few additions. Their name means "people" in the Dinka language.

They are dark African people, differing markedly from the Arabic speaking ethnic groups inhabiting northern Sudan. Dinka have been noted for their height. However, the popular belief that Dinka "often" reach more than seven feet finds no support in the scientific literature. An anthropometric survey of Dinka men published in 1995 found a mean height of 176.4cm, or roughly 5 ft 9.45 in the Ethiopian Medical Journal. [1]

History

Ancient Dinka are dated back to around 3000 B.C.E. in the Sahara Desert, where hunter-gatherers settled in the largest swamp area in the world, the southern Sudan. Dinka society spread out over the Sudan region in recent centuries, from around 1500 C.E.

The Dinka fought and defended their homeland against the Ottoman Turks in the mid-1800s and dismayed and devastated the violent attempts of slave merchants to convert them to Islam.

The Sudan People's Liberation Army, led by John Garang De Mabior, a Dinka, took up arms against the government in 1983. During the subsequent Civil War, many thousands of Dinka, along with fellow non-Dinka southerners, were massacred by government forces. The Dinka have also engaged in a separate civil war with the Nuer. Otherwise they have lived in harmonious seclusion for the past 5,000 years.

Culture

The Dinka have no centralized political authority, instead comprising of many independent but interlinked clans. Certain of those clans traditionally provide ritual chiefs, known as the "masters of the fishing spear," who provide leadership for the entire people and appear to be at least in part hereditary. As the Dinka do not have specifically organized government infrastructure, there are village elders who hold sway and influence over tribal issues, rather than wielding power and authority.

Traditionally cattle herders, the Dinka use cattle for a variety of practical purposes. The cattle play a central role in their culture and survival. The Dinka use the milk to make butter and ghee, and they innovatively found ways to use the ammonia produced by urine for washing methods, tanning hides, and washing hair. The dung is burnt in fuel fires which creates sufficient ash to keep blood-sucking ticks and other parasites at bay. This ash is also used as a sort of toothpaste in brushing their teeth, and as decorative body art. The cattle are not killed for meat, however they will be eaten in case of a sacrifice or natural death. The hides are used to make a variety of items from drum skins, clothes, belts, and ropes. Bones and horns are used as well, in decorative and practical applications.

The Dinka find it important to be familiar with their family's heritage, as certain families are not allowed to cross-marry into one another, due to inner region conflict. It is important for males have sons to carry on their family's lineage. Wealth is measured in terms of cattle, and the Dinka fathers of the brides often seek cattle as dowries. As such, it is celebrated and considered valuable to have baby girls to bring more wealth into the family unit.

As a rite of passage for a boy coming into manhood, a series of V-shaped scars is carved into the boy's forehead, which marks a specific region. These boys are then considered men, or parapuol, and serve as warriors in different arenas of Dinka life that range from protecting the cattle against enemy raiders, to guarding the tribe against natural predators such as man-eating lions. They are also eligible to marry. These parapuol have extremely deep scars, often times being carved down to and into the skull.

Leading up to the scarification process, the boy recites the names of his ancestors and sings clan songs in order to properly prepare his mind, body, and spirit for becoming a man. If the boy squeals or cries out during the flesh-carving ritual, he is considered weak, or a coward. This rite of passage occurs anytime between the ages of 10-16 years of age. The Dinka are great lovers of tradition, and even in contemporary Africa, Dinka women prefer warriors who bear the scars of the parapuol.

Pastoral strategies

As cattle are the very livelihood of the Dinka, the wetlands have a crucial role in the culture and lifestyle of the Dinka. The spirits of their ancestors are believed to inhabit the pastures and grasses surrounding the delta.

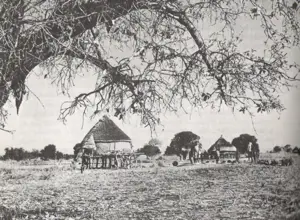

The Dinka's migrations are determined by the local climate, their agro-pastoral lifestyle responding to the periodic flooding and dryness of the area in which they live. They begin moving around May-June at the onset of the rainy season to their ‚Äúpermanent settlements‚ÄĚ of mud and thatch housing above flood level, where they plant their crops of millet and other grain products.

These rainy season settlements usually contain other permanent structures such as cattle byres (luaak) and granaries.

During the dry season (beginning about December-January), everyone except the aged, ill, and nursing mothers migrate for cattle grazing to semi-permanent dwellings in the toic lands, which are seasonally inundated or saturated by the main rivers and inland water-courses. The cultivation of sorghum, millet, and other crops begins in the highlands in the early rainy season and the harvest of crops begins when the rains are heavy in June-August. Cattle are driven to the toic in September and November when the rainfall drops off; allowed to graze on harvested stalks of the crops. [2]

Religious beliefs

The Dinka's pastoral lifestyle is also reflected in their religious beliefs and practices (which are animist in character). The term Jok refers to a group of ancestral spirits.

They have one God, Nhialic, who speaks through spirits that take temporary possession of individuals in order to speak through them. The supreme, creator god Nhialic is present in all of creation, and controls the destinies of every human, plant, and animal on Earth. Nhialic is the god of the sky and rain, and the ruler of all the spirits.

Deng, or Dengdit, is the sky god of rain and fertility empowered by Nhialic, the supreme being of all gods. Deng's mother is Abuk, the patron goddess of gardening and all women, represented by a snake. Garang is believed or assumed by some Dinka to be a suppressed god below Deng, whose spirits can influent Dinka women and sometimes men to scream.

Some of the Dinka, estimated at eight percent, practice Christianity, introduced to the region by British missionaries in the nineteenth century.

Contemporary Dinka

The experience of Dinka refugees from the civil war in Sudan was portrayed in the documentary movie Lost Boys of Sudan by Megan Mylan and Jon Shenk based on the book The Lost Boys of Sudan written by Mark Bixler. Their story was also chronicled in a book by Joan Hecht called The Journey of the Lost Boys. A fictionalized autobiography of one Dinka refugee is Dave Eggers' novel entitled What is the What. Other books on and by the Lost Boys include God Grew Tired of Us by John Bul Dau, and They Poured Fire On Us From The Sky by Alephonsion Deng, Benson Deng, and Benjamin Ajak.

Sizable groups of Dinka refugees may be found in modern locations far from their homeland, including Jacksonville, Florida and Clarkston, a working-class suburb of Atlanta, Georgia.

The majority of Dinka, however, continue to live in Southern Sudan, maintaining much of the traditional ways they have followed for generation upon generation. There has been some breakdown in the traditional patterns of life for the Dinka. Modern clothes and tools have been introduced, changing their work patterns. Many now see the value of going to the city to earn the money to buy cattle to pay a dowry so that they can marry sooner. This has disrupted the traditional redistribution of wealth among the clans with consequent jealousies. However, many girls still favor those who bear the traditional scars of the parapuol.

Well-known Dinka

Well-known Dinka include:

- William Deng Nhial (Dengdit), founder of Sudan African National Union (SANU), leading figure during the first liberation war against the Khartoum government.

- John Garang de Mabior, former First Vice President of Sudan and President of South Sudan, Commander in Chief of Sudan People's Liberation Army and chairman of Sudan People's Liberation Movement.

- Abel Alier Kuai de Kut, first southern Sudanese vice president in the government of the republic of the Sudan in the 1970s and 1980s. He helped negotiate the infamous Addis Ababa Agreement.

- Lt. Gen. Salva Kiir Mayardit, Dr. Garang's successor as First Vice President of Sudan and President of South Sudan, Commander in Chief of Sudan People's Liberation Army and chairman of Sudan People's Liberation Movement.

- Victoria Yar Arol, politician, Member of Parliament, woman activist and the first Southern Sudanese woman to graduate from a university.

- Manute Bol, NBA basketball player; one of the two tallest players in the league's history

- Francis Bok, abolitionist and former slave

- Mawut Achiecque Mach de Guarak A former child soldier in Sudan, advocate for the independence of Southern Sudan.

- Emmanuel Jal Dinka-Nuer artist/rapper with number one singles in Kenya

- Ageer Gum (Ageerdit), one of the few well known southern Sudanese women who joined the war of liberation in the 1960s. She served as a commander in the Sudanese People's Liberation Army (SPLA) until she died of natural causes in the late 1990s.

- Akut Maduot, youth leader, founder of South Sudan Next Generation Union organization.

- Akec Nyal modern folksinger in Brisbane, Australia

- Nyankol modern folksinger in Canada

- Deng Mayik Atem, one of the "Lost Boys of Sudan," a leader of Sudanese men relocated to the United States.

- John Bul Dau, one of the "Lost Boys of Sudan," author of God Grew Tired of Us, his autobiography, and subject of the documentary of the same title.

- Awino Gam, Sudanese actor, appeared in Tears of the sun and Voices of Africa.

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bixler, Mark. The Lost Boys of Sudan: An American Story of the Refugee Experience. Georgia: University of Georgia Press; New Ed., October 2006. ISBN 0820328839 ISBN 978-0820328836

- Chali D. "Anthropometric measurements of the Nilotic tribes in a refugee camp." Ethiopian Medical Journal 33(4) (1995): 211-217.

- Dau, John Bul and Michael Sweeney. God Grew Tired Of Us: A Memoir. National Geographic, 2007. ISBN 1426201141 ISBN 978-1426201141

- Deng, Francis Mading. Dinka Cosmology. London, England: Ithaca Press, 1980.

- __________. The Dinka of the Sudan. Prospect Heights, IL: Waveland Press, Inc., first published in 1972, IN: Waveland Press, February 1984. ISBN 0881330825 ISBN 978-0881330823

- Lienhardt, Godfrey. Divinity and Experience, The Religion of the Dinka. Originally published by Clarendon in 1961, Oxford University Press, USA, New Ed., July 14, 1988. ISBN 0198234058 ISBN 978-0198234050

- Seligman, C. G. and Brenda Z. Seligman. Pagan Tribes of the Nilotic Sudan.(The Ethnology of Africa) first published in 1932, London: G. Routledge & Sons, Ltd. ASIN B0006ALZNK and London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1965.

External links

All links retrieved January 29, 2024.

- Countries and their Cultures Dinka

- Orville Boyd Jenkins. The Virtual Research Centre People Profile: The Dinka of the Sudan

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.