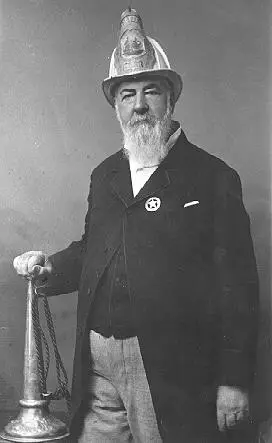

Alexander Cartwright

Alexander Cartwright II (April 17, 1820–July 12, 1892) was officially credited by the United States Congress on June 3, 1953, with inventing the modern game of baseball. Abner Doubleday was once credited with the invention of baseball, but the story is now considered a myth by sports historians, and Alexander Cartwright is now recognized as the true inventor of baseball. While establishing the Knickerbockers Base Ball club in 1845 Cartwright played a key role in formalizing the first published rules of the game, including the concept of foul territory, the distance between bases, three-out innings, and the elimination of retiring baserunners by throwing batted baseballs at them.

Alexander Cartwright was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1938 in a “pioneers" category for the Veterans' Committee ballot.

While Abner Doubleday was once credited with the invention of baseball, the story is now considered a myth by sports historians, and Cartwright has been recognized for his significant contributions.

Early years

Alexander Joy Cartwright was born on April 17, 1820, in the city of New York. He was the son of Alexander Joy Cartwright, Sr., a merchant sea captain, and his wife Esther Burlock Cartwright. He was one of seven children.

Cartwright began work in 1836 as a clerk at the age of 16 in Coit & Cochrane, a broker's office on Wall Street. He later earned his living as a clerk for Union Bank of New York. Alex married Eliza Van Wie of Albany on June 2, 1842. Three children were born to them: DeWitt (May 3, 1843, in New York), Mary (June 1, 1845, in New York), and Catherine (or Kathleen) Lee—who was known as "Kate Lee" (October 5, 1849).

Baseball

Bank hours permitted employees the opportunity to spend time outdoors before heading home by nightfall. Accordingly, it was common during the early part of the nineteenth century in New York City to see men gathering in the street or vacant lots for a game of ball after their work was done for the day playing what was called town ball. One such vacant lot was on 27th Street and 4th Avenue (Madison Square at the time) and later at 34th Street and Lexington Avenue (Murray Hill).[1]

Many of these ball-playing young men, including Cartwright, were also volunteer firemen. The first firehouse that Cartwright was associated with was Oceana Hose Company No. 36. Later, he joined Knickerbocker Engine Company No. 12, located at Pearl and Cherry Streets.

In 1845, the vacant lot in Manhattan became unavailable for use. The group was forced to look for another location to play ball. They found a playing field, Elysian Field, across the Hudson River in Hoboken, New Jersey that charged $75 a year to rent.

In order to pay the rental fees, Cartwright helped organize a ball club so that he could collect fees for the rental of Elysian Field. The club was named the "Knickerbockers," probably in honor of the fire station where Cartwright and some teammates worked. The Knickerbockers club was organized on September 23, 1845.[1]

Knickerbocker rules

The team drew up a constitution and bylaws on September 23, 1845, and 20 rules in all were adopted. The Knickerbocker rules are also synonymously known as the "Cartwright Rules." Cartwright and his friends played their first recorded game on October 6, 1845.[1]

Cartwright and his team transformed the children's game into an adult sport, chiefly by three innovations still in effect today.

First, they increased the distance between bases to an adult-length 90 feet. This was 50 percent to more than 100 percent longer than in earlier versions. Second, they brought the game an adult sense of order by dividing the field into fair and foul territory, narrowing the hitter's range to the space between the foul lines and reducing the number of defensive players needed. The number of players wasn't specified in the first rules, but by 1846 the club was playing with nine to a side, and that was later made official. And third, Knickerbocker rules forbade the practice, permitted in earlier versions, of putting out baserunners by throwing the ball at them. This change not only brought dignity to baseball but also made it safe to use a harder ball, which led to faster, sharper play.[2]

The formation of the Knickerbockers club across the Hudson River created a division in the group of Manhattan players. Several of the players refused to cross the river on a ferry to play ball because they did not like the distance away from home. Those players staying behind formed their own club, the "New York Nine."

The first baseball game between two different teams was played on June 19, 1846, at Elysian Field in Hoboken, New Jersey. The two teams, the 'Knickerbockers' and the 'New York Nine,' played with Cartwright's 20 rules. Cartwright’s team, the Knickerbockers, lost 23 to 1 to the New York Nine club in four innings. Some say that Cartwright's team lost because his best players did not want to make the trip across the river. Cartwright was the umpire during this game and fined one player 6 cents for cursing.[3]

Over the next few years, the rules of baseball spread throughout the country. Baseball was becoming the preferred sport of American adults and was drawing spectators by the thousands. Cartwright's rules would soon become part of The National Association Baseball Players Rules in 1860. The National Association Baseball Players Rules slowly evolved into today's rules of baseball.

Later years

In 1849, at the apex of the California Gold Rush, Alexander Cartwright headed west in search of fortune. Upon reaching California, he became sickened with dysentery and decided that California was not for him.[3]

He then decided to move to Honolulu, Hawaii where he became a notable citizen. Aside from his duties at the Honolulu Fire Department, Alexander became involved with many other aspects of the city through his involvement with Freemasonry. He became an adviser to Queen Emma and was the executor of her Last Will and Testament. He also was appointed Consul to Peru, and was on the financial committee for Honolulu's Centennial Celebration of American Independence held on July 4, 1876.[1]

Cartwright was one of the founders of the Honolulu Library and Reading Room in 1879 and he served as its president from 1886 to 1892.

King Kalakaua, became the first Hawaiian monarch to attend a baseball game and while Cartwright was the king's financial adviser it is unclear whether Cartwright actually instituted the playing of the game on the islands.

Their daughter "Kate Lee" died in Honolulu on November 16, 1851, and the other two Cartwright children also died young. Mary Cartwright Maitland died in 1869 at age 24, nearly three years after she married, and had no children. DeWitt died in 1870 at age 26. Two more children were born to Alexander and Eliza in Honolulu, Bruce in 1853, and Alexander III in 1855.[1]

Alexander Cartwright died on July 12, 1892, from blood poisoning from a boil on his neck six months before the Hawaiian monarchy was overthrown.[1]

Legacy

Alexander Cartwright's grandson Bruce Jr. played a central role in getting recognition for his grandfather by writing letters to Cooperstown, New York, where the National Baseball Hall of Fame was being built. As a result Cartwright was inducted into the National Baseball Hall of Fame in 1938 in a “pioneers" category for the Veterans' Committee ballot.[1]

In 1939 when the grand opening celebrations for the Hall of Fame were held in Cooperstown, August 26 was declared "National Cartwright Day." Ballplayers at Ebbets Field drank pineapple juice in a toast to Cartwright. It was the first major league baseball game broadcast on television.[1]

In 1947 Robert W. Henderson documented Cartwright's contributions to baseball in his book Bat, Ball, and Bishop, which the U. S. Congress cited in recognizing Cartwright as the inventor of the modern game.

More recent books have brought into question Cartwright's stature as the principal founder of modern baseball while not questioning that he was a prominent figure in the early development of baseball.

A granite monument in Oahu Cemetery (formerly Nuuanu Valley Cemetery) in Honolulu marks his final resting-place. A street and a park nearby were named after Cartwright. The park was originally called Makiki Park, where it was known as the first grounds used for playing baseball.[1]

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Acocella, Nick. 1996. Hoboken, Alexander Cartwright, & The Beginnings of Baseball: with a Note on the Doubleday Myth. Hoboken, NJ: Hoboken Historical Museum. OCLC 48182067

- Cartwright, Alexander Joy. 1849. The Alexander Cartwright Diary. OCLC 180851604

- Henderson, Robert W. 2001. Ball, Bat, and Bishop: The Origin of Ball Games. Urbana: University of Illinois Press. ISBN 0252069927

- Kirsch, George B. Baseball in Blue and Gray: The National Pastime during the Civil War. Princeton University Press, 2003. ISBN 0691057338

- Martin, Jay. 2009. Live All You Can: Alexander Joy Cartwright and the Invention of Modern Baseball. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231147941

- Nucciarone, Monica. 2009. Alexander Cartwright: The Life Behind the Baseball Legend. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 9780803233539

- Peterson, Harold. 1973. The Man Who Invented Baseball. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0684131854

External links

All links retrieved July 18, 2023.

- Knickerbocker Rules Baseball-almanac.com.

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.