|

|

| (64 intermediate revisions by 7 users not shown) |

| Line 1: |

Line 1: |

| − | {{claimed}} | + | {{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{approved}}{{copyedited}} |

| | + | [[Image:Second Zionist Congress.jpg|200px|right|thumb|The Second Zionist Congress, held in [[Cologne]], [[Germany]] (1898).]] |

| | + | '''Zionism''' is an international political movement that originally supported the establishment of a homeland for the Jewish people in [[Palestine]] ''(Eretz-Yisra'el)'' and continues primarily in support for the modern state of [[Israel]]. |

| | | | |

| − | '''Zionism''' is an international [[Jewish political movements|political movement]] that supports a [[homeland]] for the [[Jew]]ish people in the [[Land of Israel]].<ref>Zionism On The Web, [http://www.zionismontheweb.org/zionism_definitions.htm "Definitions of Zionism"], a compiled collection, Accessed January 10, 2007.</ref> Formally organized in the late 19th century, the movement was successful in establishing the [[Israel|State of Israel]] in [[1948]], as the world's first and only modern [[Jewish State]]. It continues primarily as support for the state and government of Israel and its continuing status as a homeland for the Jewish people.<ref>"An international movement originally for the establishment of a Jewish national or religious community in Palestine and later for the support of modern Israel." ("Zionism," Webster's 11th Collegiate Dictionary). See also [http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9078399/Zionism "Zionism"], ''Encyclopedia Britannica'', which describes it as a "Jewish nationalist movement that has had as its goal the creation and support of a Jewish national state in Palestine, the ancient homeland of the Jews (Hebrew: Eretz Yisra'el, “the Land of Israel”)," and The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition, which defines it as "A Jewish movement that arose in the late 19th century in response to growing anti-Semitism and sought to reestablish a Jewish homeland in Palestine. Modern Zionism is concerned with the support and development of the state of Israel." </ref> Described as a "[[diaspora]] [[nationalism]],"<ref>[[Ernest Gellner]], [[1983]]. Nations and Nationalism (First edition), p 107-108.</ref> its proponents, regard it as a [[national liberation]] movement whose aim is the [[self-determination]] of the Jewish people.<ref>A national liberation movement:

| + | The term "Zionism" is derived from the word Zion (Hebrew: '''ציון'''—Tzi-yon), referring to [[Mount Zion]], a small mountain near [[Jerusalem]]. In several biblical verses, the [[Israelites]] were called the people of Zion (Isaiah 12:6; Joel 2:23, for example). While Zionism is based in part upon the religious tradition linking the Jewish people to the Land of Israel, the modern Zionist movement was mainly secular, beginning largely as a response by European Jewry to [[antisemitism]] across Europe. Several types of Zionism emerged from these beginnings, including Labor Zionism, Liberal Zionism, Revisionist Zionism, and Religious Zionism. |

| − | *"Zionism is a modern national liberation movement whose roots go far back to Biblical times." (Rockaway, Robert. [http://www.wzo.org.il/en/resources/view.asp?id=111 Zionism: The National Liberation Movement of The Jewish People], [[World Zionist Organization]], January 21, 1975, accessed August 17, 2006).

| |

| − | *"The aim of Zionism was principally the liberation and self-determination of the Jewish people...", [[Shlomo Avineri]]. ([http://www.hagshama.org.il/en/resources/view.asp?id=1551 Zionism as a Movement of National Liberation], Hagshama department of the [[World Zionist Organization]], December 12, 2003, accessed August 17, 2006).

| |

| − | *"Political Zionism, the national liberation movement of the Jewish people, emerged in the 19th century within the context of the liberal nationalism then sweeping through Europe." (Neuberger, Binyamin. [http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/MFAArchive/2000_2009/2001/8/Zionism%20-%20an%20Introduction Zionism - an Introduction], Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, August 20, 2001, accessed August 17, 2006).

| |

| − | *"The vicious diatribes on Zionism voiced here by Arab delegates may give this Assembly the wrong impression that while the rest of the world supported the Jewish national liberation movement the Arab world was always hostile to Zionism." ([[Herzog, Chaim|Chaim Herzog]], [http://www.mfa.gov.il/MFA/Foreign%20Relations/Israels%20Foreign%20Relations%20since%201947/1974-1977/129%20Statement%20in%20the%20General%20Assembly%20by%20Ambassado Statement in the General Assembly by Ambassador Herzog on the item "Elimination of all forms of racial discrimination", 10 November 1975.], Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs, November 11, 1975, accessed August 17, 2006).

| |

| − | *[http://sicsa.huji.ac.il/WUPJ-2004-Items%205%20and%209.htm Zionism: one of the earliest examples of a national liberation movement], written submission by the World Union for Progressive Judaism to the U.N. Commission on Human Rights, Sixtieth session, Item 5 and 9 of the provisional agenda, January 27, 2004, accessed August 17, 2006.

| |

| − | *"Zionism is the national liberation movement of the Jewish people and the state of Israel is its political expression." ([[Shlaim, Avi|Avi Shlaim]], [http://www.iht.com/articles/2005/02/04/edshlaim_ed3_.php A debate : Is Zionism today the real enemy of the Jews?], ''[[International Herald Tribune]]'', February 4, 2005, accessed August 17, 2006.

| |

| − | *"But Zionism is the national liberation movement of the Jewish people." ([[Melanie Phillips|Philips, Melanie]]. [http://www.melaniephillips.com/diary/archives/Zionism%20MP.pdf Zionism today is the real enemy of the Jews’: opposed by Melanie Phillips], www.melaniephilips.com, accessed August 17, 2006.

| |

| − | *"Zionism, the national liberation movement of the Jewish people, brought about the establishment of the State of Israel, and views a Jewish, Zionist, democratic and secure State of Israel to be the expression of the common responsibility of the Jewish people for its continuity and future." ([http://www.hadassah.org/pageframe.asp?section=education&page=jerusalem_program.html&header=jerusalem_program&size=60 What is Zionism (The Jerusalem Program)], [[Hadassah]], accessed August 17, 2006.

| |

| − | *"Zionism is the national liberation movement of the Jewish people." (Harris, Rob. [http://www.jewishtelegraph.com/ire_1.html Ireland's Zionist slurs like Iran, says Israel], ''[[Jewish Telegraph]]'', December 16, 2005, accessed August 17, 2006.</ref> Opposition to Zionism has arisen on a number of grounds, ranging from religious objections to competing claims of nationalism to political dissent that considers the ideology either immoral or impractical.<ref>Noam Chomsky, ''The Chomsky Reader''</ref>

| |

| | | | |

| − | While Zionism is based in part upon [[Judaism|religious tradition]] linking the Jewish people to the Land of Israel, where the concept of Jewish [[nationhood]] is thought to have first evolved somewhere between 1200 B.C.E. and the late [[Second Temple]] era,<ref>"...from Zion, where King David fashioned the first Jewish nation" (Friedland, Roger and Hecht, Richard ''To Rule Jerusalem'', p. 27).</ref><ref>"By the late Second Temple times, when widely held Messianic beliefs were so politically powerful in their implications and repercussions, and when the significance of political authority, territorial sovereignty, and religious belief for the fate of the Jews as a people was so widely and vehemently contested, it seems clear that Jewish nationhood was a social and cultural reality". (Roshwald, Aviel. "Jewish Identity and the Paradox of Nationalism", in Berkowitz, Michael (ed.). ''Nationalism, Zionism and Ethnic Mobilization of the Jews in 1900 and Beyond'', p. 15).</ref> the modern movement was mainly [[Secularism|secular]], beginning largely as a response by [[Ashkenazi Jews|European Jewry]] to rampant [[antisemitism]] across the continent.<ref>Largely a response to anti-Semitism:

| + | The modern Zionist movement was formally established by the Austro-Hungarian journalist [[Theodor Herzl]] in the late nineteenth century. In response to the tragedy of European Jews during the [[Holocaust]], Zionism became the dominant Jewish political movement after [[World War II]]. The movement eventually succeeded in establishing the state of Israel in 1948, as the world's first and only modern Jewish state. |

| − | *"A Jewish movement that arose in the late 19th century in response to growing anti-Semitism and sought to reestablish a Jewish homeland in Palestine." ("Zionism", The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition).

| |

| − | *"The Political Zionists conceived of Zionism as the Jewish response to anti-Semitism. They believed that Jews must have an independent state as soon as possible, in order to have a place of refuge for endangered Jewish communities." (Wylen, Stephen M. ''Settings of Silver: An Introduction to Judaism'', Second Edition, Paulist Press, 2000, p. 392).

| |

| − | *"Zionism, the national movement to return Jews to their homeland in Israel, was founded as a response to anti-Semitism in western Europe and to violent persecution of Jews in eastern Europe." (Calaprice, Alice. ''The Einstein Almanac'', Johns Hopkins University Press, 2004, p. xvi).

| |

| − | *"The major response to anti-semitism was the emergence of Zionism under the leadership of [[Theodor Herzl]] in the late nineteenth century." (Matustik, Martin J. and Westphal, Merold. ''Kierkegaard in Post/Modernity'', Indiana University Press, 1995, p. 178).

| |

| − | *"Zionism was founded as a response to anti-Semitism, principally in Russia, but took off when the worst nightmare of the Jews transpired in western Europe under Nazism." (Hollis, Rosemary. {{PDFlink|[http://www.chathamhouse.org.uk/pdf/int_affairs/inta_378.pdf The Israeli-Palestinian road block: can Europeans make a difference?]|57.9 [[Kibibyte|KiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 59386 bytes —>}}, ''[[International Affairs]]'' 80, 2 (2004), p. 198).</ref> At first one of several [[Jewish political movements]] offering alternative responses to the position of Jews in [[Europe]], Zionism gradually gained more support, and [[the Holocaust]] accelerated Jewish immigration to the Land of Israel.

| |

| | | | |

| − | ==Terminology==

| + | Although some Israeli and American Jews are critical of Zionism, anyone who supports the existence of Israel as a Jewish homeland is technically defined as a Zionist. In this sense, despite widespread opposition, Zionism must be viewed as one of the most successful modern political movements. |

| | | | |

| − | The word "Zionism" itself derived from the word "[[Zion]]" ([[Hebrew language|Hebrew]]: ציון, ''Tz-yon''), one of the names of [[Jerusalem]] and the [[Land of Israel]], as mentioned in the [[Bible]].

| + | ==History== |

| − | [[Image:1892 Self Emancipation by Birnbaum.jpg|thumb|left|150px|1892 issue of ''Self Emancipation'' by N. Birnbaum describing the principles of Zionism]]

| + | {| class="wikitable" align="right" |

| − | It was coined as a term for Jewish [[nationalism]] by [[Austria]]n [[Jew]]ish publisher [[Nathan Birnbaum]], founder of the first nationalist Jewish students' movement ''Kadimah'', in his journal ''Selbstemanzipation'' (''Self Emancipation'') in 1890. (Birnbaum eventually turned against political Zionism and became the first secretary-general of the anti-Zionist [[Haredi Judaism|Haredi]] movement [[Agudat Israel]].)<ref>De Lange, Nicholas, ''An Introduction to Judaism'', Cambridge University Press (2000), p. 30. ISBN 0-521-46624-5.</ref>

| + | |+ Demographics in Palestine<ref>Gorny (1987), 5. </ref> |

| − | | + | |- |

| − | Since the founding of the State of Israel, the term "Zionism" is generally considered to mean support for Israel as a Jewish [[nation state]]. However, a variety of different, and sometimes competing, ideologies that support Israel fit under the general category of Zionism, such as [[Religious Zionist Movement|Religious Zionism]], [[Revisionist Zionism]], and [[Labor Zionism]]. Thus, the term is also sometimes used to refer specifically to the programs of these ideologies, such as efforts to encourage [[Aliyah|Jewish emigration to Israel]].

| + | ! width="50"|year |

| − | | + | ! width="80"|Jews |

| − | Certain individuals and groups have used the term "Zionism" as a pejorative to justify attacks on Jews. According to historians [[Walter Laqueur]], [[Howard Sachar]] and [[Jack Fischel]] among others, in some cases, the label "Zionist" is also used as a [[euphemism]] for Jews in general by apologists for [[antisemitism]].<ref>Misuse of the term "Zionism":

| + | ! width="80"|Non-Jews |

| − | *"... behind the cover of "anti-Zionism" lurks a variety of motives that ought to be called by their true name. When, in the 1950s under Stalin, the Jews of the Soviet Union came under severe attack and scores were executed, it was under the banner of anti-Zionism rather than anti-Semitism, which had been given a bad name by Adolf Hitler. When in later years the policy of Israeli governments was attacked as racist or colonialist in various parts of the world, the basis of the criticism was quite often the belief that Israel had no right to exist in the first place, not opposition to specific policies of the Israeli government. Traditional anti-Semitism has gone out of fashion in the West except on the extreme right. But something we might call post-anti-Semitism has taken its place. It is less violent in its aims, but still very real. By and large it has not been too difficult to differentiate between genuine and bogus anti-Zionism. The test is twofold. It is almost always clear whether the attacks are directed against a specific policy carried out by an Israeli government (for instance, as an occupying power) or against the existence of Israel. Secondly, there is the test of selectivity. If from all the evils besetting the world, the misdeeds, real or imaginary, of Zionism are singled out and given constant and relentless publicity, it can be taken for granted that the true motive is not anti-Zionism but something different and more sweeping." ([[Walter Laqueur|Laqueur, Walter]]: ''Dying for Jerusalem: The Past, Present and Future of the Holiest City'' (Sourcebooks, Inc., 2006) ISBN 1-4022-0632-1. p. 55)

| + | |- |

| − | *"In late July 1967, Moscow launched an unprecedented propaganda campaign against Zionism as a "world threat." Defeat was attributed not to tiny Israel alone, but to an "all-powerful international force." ... In its flagrant vulgarity, the new propaganda assault soon achieved Nazi-era characteristics. The Soviet public was saturated with racist canards. Extracts from Trofim Kichko's notorious 1963 volume, ''Judaism Without Embellishment'', were extensively republished in the Soviet media. Yuri Ivanov's ''Beware: Zionism'', a book essentially replicated ''[[The Protocols of the Elders of Zion]]'', was given nationwide coverage." ([[Howard Sachar]]: ''A History of the Jews in the Modern World'' (Knopf, NY. 2005) p.722

| + | | align="center"|1800 |

| − | *See also [[Rootless cosmopolitan]], [[Doctors' Plot]], [[Zionology]], [[Polish 1968 political crisis]]</ref>

| + | | align="center"|6,700 |

| − | | + | | align="center"|268,000 |

| − | Zionism should be distinguished from [[Territorialism]] which was a Jewish nationalist movement calling for a Jewish homeland, but not necessarily in Palestine. During the early history of Zionism, a number of proposals were made for settling Jews outside of Europe but these all ultimately were rejected or failed. The debate over these proposals helped define the nature and focus of the Zionist movement.

| + | |- |

| − | | + | | align="center"|1880 |

| − | ==Historical background==

| + | | align="center"|24,000 |

| − | {{main|Jewish history}}

| + | | align="center"|525,000 |

| − | The desire of Jews to return to their ancestral homeland has remained a universal Jewish theme since the defeat of the [[Great Jewish Revolt]], and the [[destruction of Jerusalem]] by the [[Roman Empire]] in the year [[70]], the later defeat of [[Bar Kokhba's revolt]] in [[135]], and the dispersal of the Jews to other parts of the Empire that followed.<ref>[http://www.wzo.org.il/en/resources/view.asp?id=1527&subject=28 Yearning for Zion] by Briana Simon (WZO)</ref> (During the [[Hellenistic Age]] many Jews had decided to leave Palestine to live in other parts of the [[Mediterranean]] basin by their own free will;<ref>[http://classes.maxwell.syr.edu/his301-001/jeishh_diaspora_in_greece.htm The Jewish Diaspora in the Hellenistic Period]</ref> famous figures associated with these migrations include, for example, [[Philo of Alexandria]]). Due to the disastrous results of the revolt, what had been a human-driven movement to regain national sovereignty based on religious inspiration, became, after centuries of broken hopes associated with one "false messiah" after another, a movement in which much of the human element of messianic deliverance had been replaced by a trust in [[God|Divine]] providence. Although Jewish nationalism in ancient times had always had religious connotations—from the [[Maccabees|Maccabean Revolt]] to the various Jewish revolts during Roman rule, and even during the Medieval period when intermittently national hopes were incarnated in the "[[List of messiah claimants|false messianism]]" of [[Shabbatai Zvi]]—it was not until the rise of ideological and political Zionism and its renewed belief in human-based action toward Jewish national aspirations that the notion of returning to the homeland once again became widespread among the Jewish people.

| + | |- |

| − | | + | | align="center"|1915 |

| − | Jews lived continuously in the Land of Israel even after the Bar Kokhba's revolt, and indeed there is much historical evidence of vibrant communities there continually throughout the past two millennia. For example, the [[Jerusalem Talmud]] was created in the centuries following that revolt. The inventors of [[niqqud|Hebrew vowel-signs]], the [[Masoretes]] (ba'alei hamasorah, Hebrew בעלי המסורה), groups of scribes in 7th and 11th centuries were based primarily in [[Tiberias]] and [[Jerusalem]]; and so forth. The slow and gradual decline of the Palestinian Jews occurred across a period of several centuries, and can be attributed to Hadrian's crushing of Bar Kokhba's revolt, the Arab conquest of Palestine in the 600s, the [[Crusade]]r wars in the 11th century and beyond, and the inefficiencies of the [[Ottoman Empire]] from the 15th century on, by which time the land had greatly decreased in fertility and its economy was virtually nil.

| + | | align="center"|87,500 |

| − | | + | | align="center"|590,000 |

| − | Despite this decline, several proto-Zionist movements over the centuries saw the revival of particular Jewish communities, such as the medieval community of [[Safed]], the population of which was bolstered by Jews fleeing Christian persecution following the ''[[Reconquista]]'' of ''[[Al-Andalus]]'' (the Muslim name of the [[Iberian peninsula]]). In [[Portugal]] during this period, Jews were expelled by [[Manuel I of Portugal|Manuel I]] or forced to convert to Christianity, — a policy that created the [[Marrano]] Jews, from which [[Baruch Spinoza|Spinoza]] came. According to chronicler [[Jerónimo Osório]], this followed the enslavement and partial expulsion of Jewish refugees from Spain during the reign of [[John II of Portugal|John II]]. The persecution of those with Jewish blood, no matter what faith, continued in Portugal until well into the eighteenth century. In 1536, [[John III of Portugal|John III]] established the [[Portuguese Inquisition]], mirroring the more famous [[Spanish Inquisition]], which imposed the ''[[limpieza de sangre]]'' doctrine, breaking away with the [[Caliph of Córdoba]]'s tolerance.

| + | |- |

| − | | + | | align="center"|1931 |

| − | ===Aliyah and the ingathering of the exiles=== | + | | align="center"|174,000 |

| − | {{main|Aliyah}}

| + | | align="center"|837,000 |

| − | | |

| − | Return to the Land of Israel had remained a recurring theme among generations of [[Jewish diaspora|diaspora Jews]], particularly in [[Passover]] and [[Yom Kippur]] prayers which traditionally concluded with, "Next year in Jerusalem", and in the thrice-daily [[Amidah]] (Standing prayer).<ref>"Sound the great shofar for our freedom, raise the banner to gather our exiles and gather us together from the four corners of the earth (Isaiah 11:12) Blessed are you, O Lord, Who gathers in the dispersed of His people Israel."</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ''Aliyah'' (immigration to Israel) has always been considered to be a praiseworthy act for Jews according to [[Halakha|Jewish law]], and is included as a commandment in most versions of the [[613 mitzvot|613 commandments]]. Although not found in the version of [[Maimonides]], his other writings indicate that he considered return to the Land of Israel a matter of extreme importance for Jews.<ref>In ''Hilchos Melachim'' 5:12 Maimonides says "whoever lives in the Land of Israel remains without sin". In ''Hilchos Avadim'' 8:9 he says that if a Jewish slave wishes to move to the Land of Israel, his master must move with him, or sell him to someone who will move to the Land of Israel. In ''Hilchos Avadim'' 8:10 he states that if a slave flees to the Land of Israel, the Jewish court frees him, and the [[Talmud]] (Kesubos 110) lists the reason as being the commandment to settle in the Land of Israel.</ref>

| |

| − | From the [[Middle Ages]] and onwards, a number of famous Jews (and often their followers) immigrated to the Land of Israel. These included [[Nahmanides]], [[Yechiel of Paris]] with several hundred of his students, [[Yosef Karo]], [[Menachem Mendel of Vitebsk]] and 300 of his followers, and over 500 disciples (and their families) of the [[Vilna Gaon]] known as [[Perushim]], among others.

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Establishment of the Zionist movement==

| |

| − | ===Proto-Zionism===

| |

| − | The [[Haskala]] of Jews in European countries in the [[18th century|18th]] and [[19th century|19th centuries]] following the [[French Revolution]], and the spread of western liberal ideas among a section of newly emancipated Jews, created for the first time a class of [[secular Jews]] who absorbed the prevailing ideas of [[rationalism]], [[romanticism]] and, most importantly, [[nationalism]]. Jews who had abandoned Judaism, at least in its traditional forms, began to develop a new Jewish identity, as a "nation" in the European sense. They were inspired by various national struggles, such as those for [[Germany|German]] and [[Italy|Italian]] unification, and for [[Poland|Polish]] and [[Hungary|Hungarian]] independence. If Italians and Poles were entitled to a homeland, they asked, why were Jews not so entitled?

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Image:1844 Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews p1.jpg|thumb|1844 ''Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews'' by [[Mordecai Manuel Noah|Mordecai Noah]], page one. The [[:Image:1844 Discourse on the Restoration of the Jews p2.jpg|second page]] shows the map of the Land of Israel]]

| |

| − | A precursor to the Zionist movement of the later 1800s occurred with the 1820 attempt by journalist, playwright and American-born diplomat [[Mordecai Manuel Noah]] to establish a Jewish homeland on [[Grand Island, New York]], (north of [[Buffalo, New York]], USA). In 1840s, Noah advocated the "Restoration of the Jews" in the Land of Israel.<ref>Rubinstein, Hilary L. (Ed.), Rubinstein, William D, Cohn-Sherbok, Dan, Edelheit, Abraham J. ''The Jews in the Modern World: A History Since 1750'', pp.303, Oxford University Press (2002), ISBN 0-340-69163-8</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Rise of modern political Zionism===

| |

| − | Before the 1890s there had already been attempts to settle Jews in Palestine, which was in the 19th century a part of the [[Ottoman Empire]], inhabited (in 1890) by about 520,000 people, mostly [[Muslim]]s and [[Christian]] [[Arab]]s—but including 20-25,000 Jews. [[Pogrom]]s in the [[Russian Empire]] led Jewish philanthropists such as the [[Moses Haim Montefiore|Montefiores]] and the [[Rothschild]]s to sponsor agricultural settlements for Russian Jews in Palestine in the late 1870s, culminating in a small group of immigrants from Russia arriving in the country in 1882. This has become known in Zionist history as the [[First Aliyah]].<ref> Scharfstein, Sol, ''Chronicle of Jewish History: From the Patriarchs to the 21st Century'', p.231, KTAV Publishing House (1997), ISBN 0-88125-545-9</ref> ''Aliyah'' is a Hebrew word meaning "ascent," referring to the act of spiritually "ascending" to the Holy Land.

| |

| − | | |

| − | While Zionism is based heavily upon [[Judaism|Jewish religious tradition]] linking the Jewish people to the Land of Israel, the modern movement was mainly [[Secularism|secular]], beginning largely as a response to rampant [[anti-Semitism]] in late 19th century [[Europe]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Moses Hess]]'s 1862 work ''Rome and Jerusalem; The Last National Question'' argued for the Jews to settle in [[Palestine (region)|Palestine]] as a means of settling the [[national question]]. Hess proposed a [[socialist state]] in which the Jews would become [[agrarianism|agrarianised]] through a process of "redemption of the soil" that would transform the Jewish community into a true nation in that Jews would occupy the productive layers of society rather than being an intermediary non-productive merchant class, which is how he perceived European Jews. Hess, along with later thinkers such as [[Nahum Syrkin]] and [[Ber Borochov]], is considered a founder of [[Socialist Zionism]] and [[Labour Zionism]] and one of the intellectual forebears of the [[kibbutz]] movement.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In the same year 1862, German Orthodox Rabbi [[Zvi Hirsch Kalischer]] published his tractate ''Derishat Zion'', positing that the salvation of the Jews, promised by the Prophets, can come about only by self-help.<ref>[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=56&letter=K Zvi Hirsch Kalischer] (Jewish Encyclopedia)</ref> His ideas contributed to the [[Religious Zionism]] movement.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[image:pinsker_Autoemanicipation.jpg|left|thumb|150px|''[[Auto-Emancipation]]'' by J.L. Pinsker, 1882]]

| |

| − | Early Zionist groups such as [[Hovevei Zion|Hibbat Zion]] were active in the 1880s in the [[Eastern Europe]] where emancipation had not occurred to the extent it did in [[Western Europe]] (or at all). The massive [[Anti-Semitism|anti-Jewish]] [[pogroms]] following the assassination of [[Russian history, 1855-1892|Tsar Alexander II]] made emancipation seem more elusive than ever, and influenced [[Judah Leib Pinsker]] to publish the pamphlet ''[[Auto-Emancipation]]'' in 1882. In 1890, the "Society for the Support of Jewish Farmers and Artisans in Syria and Eretz Israel" (better known as the [[Odessa Committee]]) was officially registered as a [[charitable organization]] in the [[Russian Empire]] and by 1897 it counted over 4,000 members.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[United States|American]] [[Protestantism|Protestant]] [[Christian Zionism|Christian Zionists]] such as [[William Eugene Blackstone]] also pursued the Zionist ideal during late 19th century, especially in the American [[Blackstone Memorial]] (1891).

| |

| − | | |

| − | {| style="float; margin: 10px; border: solid 1px #bbb; width: 298px;" align="right"

| |

| − | | align="center" | | |

| − | [[Image:Theodore Herzl.jpg|150px|]]

| |

| − | [[Image:DE Herzl Judenstaat 01.gif|130px|]]

| |

| | |- | | |- |

| − | | T. Herzl and his 1896 book ''The Jewish State'' | + | | align="center"|1947 |

| | + | | align="center"|630,000 |

| | + | | align="center"|1,310,000 |

| | |} | | |} |

| | + | In Jewish tradition, ''Eretz Israel,'' or [[Zion]], is a land promised to the Jews by God, dating back to God's covenant with [[Abraham]], [[Isaac]], and [[Jacob]]. However, although there has been a constant presence of Jews in the [[Land of Israel]], most Jews have lived in exile since the first or second century C.E. |

| | | | |

| − | A key event said to trigger the modern Zionist movement was the [[Dreyfus Affair]], which erupted in [[France]] in 1894. Jews were profoundly shocked to see this outbreak of anti-Semitism in a country which they thought of as the home of enlightenment and liberty. Among those who witnessed the Affair was an Austro-Hungarian (born in [[Budapest]], lived in [[Vienna]]) Jewish journalist, [[Theodor Herzl]], who published his pamphlet ''[[Der Judenstaat]]'' ("The Jewish State") in 1896 and described the Affair as a turning point—prior to the Affair, Herzl had been [[anti-Zionist]], afterwards he became ardently [[pro-Zionist]]. In [[Austria]], [[Theodor Herzl]] took the idea of political Zionism and infused it with a new an practical urgency. Herzl brought the [[World Zionist Organization]] into being; its First Congress met at [[Basle]] in 1897<ref>[http://fusion.dalmatech.com/%7Eadmin24/files/zionism_in-britishpalestine.pdf Zionism & The British In Palestine], by [[Arjun Sethi|Sethi,Arjun]] (University of Maryland) January 2007, accessed May 20, 2007.</ref>

| + | Jews from [[Babylonia]], [[Asia Minor]], and [[Europe]] are known to have immigrated to Palestine and lived in the region throughout the last millennium, though not in large numbers.<ref>Smith (2001), 1-12, 33-38.</ref> In the nineteenth century, a current in Judaism supporting the re-establishment of a Jewish homeland in the traditional Land of Israel grew in popularity. |

| | | | |

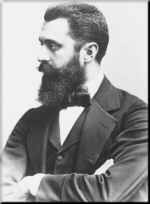

| − | ===Agricultural settlements===

| + | [[Image:Theodore Herzl.jpg|thumb|200px|Theodore Herzl]] |

| − | {{main|Mikveh Israel Settlement|Bilu|Hovevei Zion}}

| |

| − | [[Image:First_aliyah_BILU_in_kuffiyeh.jpg|left|thumb|250px|The first aliyah: [[Biluim]] used to wear the traditional Arab headdress, the [[kaffiyeh]]]] | |

| − | Founded in 1878, [[Petah Tikva]] was the first [[Israeli settlement|Zionist settlement]]. It was inhabited by former residents of [[Jerusalem]] hoping to escape the cramped quarters of [[Jerusalem's Old City walls]].

| |

| | | | |

| − | [[Rishon LeZion]] was founded on [[31 July]] [[1882]] by a group of ten members of the Zionist group [[Hovevei Zion]] from [[Kharkov]] (today's [[Ukraine]]). Led by [[Zalman David Levontin]], they purchased 835 acres (3.4 km²) of land for this purpose near an [[Arab]] village named [[Uyun Qara]]. The land was owned by Tzvi Leventine and was purchased by the "Pioneers of Jewish Settlement Committee" that was formed in [[Jaffa, Israel|Jaffa]], the port of arrival for many of the immigrants to the area. | + | Jewish immigration to Palestine started in earnest in 1882. The so-called [[First Aliyah]] (first return) saw the arrival of about 30,000 Jews over 20 years. Most [[Jewish refugees|immigrants]] came from [[Russia]], where [[antisemitism]] was a major problem. They founded a number of agricultural settlements with financial support from Jewish philanthropists in Western Europe. The [[Second Aliyah]] started in 1904. Further immigrations followed between the two World Wars, fueled in the 1930s by [[Nazi]] persecution. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Early Zionist initiatives===

| + | In the 1890s, [[Theodor Herzl]] infused Zionism with a new and practical urgency. He founded the [[World Zionist Organization]] (WZO) and, together with [[Nathan Birnbaum]], planned its first congress at [[Basel]] in 1897. This was followed a year later by a second congress held in [[Cologne]]. |

| − | {{Unreferencedsect|date=May 2007}}

| |

| − | In 1883, [[Nathan Birnbaum]], nineteen years old, founded ''Kadimah'', the first Jewish Students Association in Vienna. In 1884 the first issue of ''Selbstemanzipation'' or ''Self [[Political emancipation|Emancipation]]'' appeared, completely made by Nathan Birnbaum himself.

| |

| | | | |

| − | [[Image:Herzelandsecondcongress.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Theodor Herzl]] addresses the Second Zionist Congress in 1898.]] | + | The ruling power of the area, up until 1917, was the [[Ottoman Empire]], followed by Britain on behalf of the League of Nations until after [[WWII]]. Lobbying by [[Chaim Weizmann]] and others culminated in the [[Balfour Declaration of 1917]] by the British government. This declaration endorsed the creation of a Jewish homeland in [[Palestine]]. In 1922, the [[League of nations]] endorsed the declaration in the [[British mandate of Palestine|mandate]] it gave to Britain: |

| − | Together with Nathan Birnbaum, Herzl planned the first Zionist Congress in Basel. During the congress, the following agreement was reached:

| |

| − | <blockquote>

| |

| − | Zionism seeks to establish a home for the Jewish people in Eretz-Israel secured under public law. The Congress contemplates the following means to the attainment of this end:

| |

| − | *The promotion by appropriate means of the settlement in Eretz-Israel of Jewish farmers, artisans, and manufacturers.

| |

| − | *The organization and uniting of the whole of Jewry by means of appropriate institutions, both local and international, in accordance with the laws of each country.

| |

| − | *The strengthening and fostering of Jewish national sentiment and national consciousness.

| |

| − | *Preparatory steps toward obtaining the consent of governments, where necessary, in order to reach the goals of Zionism.

| |

| − | </blockquote>

| |

| | | | |

| − | After the First Zionist Congress, the [[World Zionist Organization]] met every year first four years, later they gathered every second year till the Second World War. After the war the Congress met every four years until present time.

| + | <blockquote>The Mandatory (Britain)… will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home, as laid down in the preamble, and the development of self-governing institutions, and also for safeguarding the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion.<ref>''League of Nations Palestine Mandate,'' July 24, 1922.</ref></blockquote> |

| | | | |

| − | The WZO's initial strategy was to obtain permission of the [[Ottoman Empire#Sultans|Ottoman Sultan]] [[Abd-ul-Hamid II]] to allow systematic Jewish settlement in Palestine. The good offices of the German Emperor, [[William II, German Emperor|Wilhelm II]], were sought, but nothing came of this. Instead, the WZO pursued a strategy of building a homeland through persistent small-scale immigration, and the founding of such bodies as the [[Jewish National Fund]] in 1901 and the Anglo-Palestine Bank in 1903.

| + | However, Palestinian Arabs resisted Zionist migration. There were riots in 1920, 1921, and 1929, sometimes accompanied by massacres of Jews. Britain continued to support Jewish immigration in principle, but in reaction to Arab violence imposed restrictions on Jewish immigration to the area. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Alternative proposals=== | + | {| class="wikitable" align="right" |

| − | {{Unreferencedsect|date=May 2007}}

| + | |+ Population of Palestine by religions<ref>United Nations Special Committee on Palestine, [http://domino.un.org/UNISPAL.NSF/eed216406b50bf6485256ce10072f637/07175de9fa2de563852568d3006e10f3! Report to the General Assembly.] Retrieved June 30, 2008.</ref> |

| − | Before 1917 some Zionist leaders took seriously proposals for Jewish homelands in places other than Palestine. Herzl's ''Der Judenstaat'' argued for a Jewish state in either Palestine, "our ever-memorable historic home", or [[Argentina]], "one of the most fertile countries in the world". In 1903 British cabinet ministers suggested the [[British Uganda Program]], land for a Jewish state in "[[Uganda]]" (in today's [[Kenya]]). Herzl initially rejected the idea, preferring Palestine, but after the April 1903 [[Kishinev pogrom]] Herzl introduced a controversial proposal to the Sixth Zionist Congress to investigate the offer as a temporary measure for Russian Jews in danger. Notwithstanding its emergency and temporary nature, the proposal still proved very divisive, and widespread opposition to the plan was fueled by a walkout led by the Russian Jewish delegation to the Congress. Nevertheless, a majority voted to establish a committee for the investigation of the possibility, and it was not dismissed until the Seventh Zionist Congress in 1905.

| + | |- |

| | + | ! width="50"|year |

| | + | ! width="80"|Muslims |

| | + | ! width="80"|Jews |

| | + | ! width="80"|Christians |

| | + | ! width="80"|Others |

| | + | |- |

| | + | | align="right"|1922 |

| | + | | align="right"|486,177 |

| | + | | align="right"|83,790 |

| | + | | align="right"|71,464 |

| | + | | align="right"|7,617 |

| | + | |- |

| | + | | align="right"|1931 |

| | + | | align="right"|493,147 |

| | + | | align="right"|174,606 |

| | + | | align="right"|88,907 |

| | + | | align="right"|10,101 |

| | + | |- |

| | + | | align="right"|1941 |

| | + | | align="right"|906,551 |

| | + | | align="right"|474,102 |

| | + | | align="right"|125,413 |

| | + | | align="right"|12,881 |

| | + | |- |

| | + | | align="right"|1946 |

| | + | | align="right"|1,076,783 |

| | + | | align="right"|608,225 |

| | + | | align="right"|145,063 |

| | + | | align="right"|15,488 |

| | + | |} |

| | | | |

| − | In response to this, the [[Jewish Territorialist Organization]] (ITO) led by [[Israel Zangwill]] split off from the main Zionist movement. The [[territorialism|territorialists]] attempted to establish a Jewish homeland wherever possible, but went into decline after 1917 and the ITO was dissolved in 1925. From that time Palestine was the sole focus of Zionist aspirations. In 1928, the [[Soviet Union]] established a [[Jewish Autonomous Oblast]] in the [[Russian Far East]] but the effort failed to meet expectations and as of 2002 Jews constitute only about 1.2% of its population. | + | In 1933, [[Hitler]] came to power in Germany. In 1935, the [[Nuremberg Laws]] made German Jews (and later [[Anschluss|Austrian]] and [[Czech Jews]]) stateless refugees. Similar rules were subsequently applied by [[Axis powers|Nazi allies]] throughout much of Europe. The subsequent growth in Jewish migration led to the [[1936-1939 Arab revolt in Palestine]], which in turn led the British to establish the [[Peel Commission]] to investigate the situation. The commission called for a two-state solution and compulsory transfer of populations. This solution was rejected by the British and instead the [[White Paper of 1939]] proposed an end to Jewish immigration by 1944, with a further 75,000 to be admitted by then. In principle, the British stuck to this policy until the end of the Mandate. |

| | | | |

| − | ===New Jewish mentality===

| + | After WWII and [[the Holocaust]], support for Zionism increased, especially among Holocaust survivors and those who sympathized with them. However, restrictions on Jewish immigration to the future Jewish homeland led to an increased sense of urgency and desperation among some Zionists. The British were attacked in Palestine by certain Zionist factions, the best known being the 1946 [[King David Hotel bombing]]. Unable to resolve the conflict, the British referred the issue to the newly created [[United Nations]]. |

| − | {{Unreferencedsect|date=May 2007}}

| |

| − | One of the major motivations for Zionism was the belief that the Jews needed to return to their historic homeland, not just as a refuge from anti-Semitism, but also to govern themselves as an independent nation. Some Zionists, mainly socialist Zionists, believed that the Jews' centuries of being oppressed in anti-Semitic societies had reduced Jews to a meek, vulnerable, despairing existence which invited further anti-Semitism. They argued that Jews should redeem themselves from their history by becoming farmers, workers, and soldiers in a country of their own. These socialist Zionists generally rejected religion as perpetuating a "[[Diaspora]] mentality" among the Jewish people.

| |

| | | | |

| − | One such Zionist ideologue, [[Ber Borochov]], continuing from the work of [[Moses Hess]], proposed the creation of a socialist society that would correct the "inverted pyramid" of Jewish society. Borochov believed that Jews were forced out of normal occupations by Gentile hostility and competition, using this dynamic to explain the relative predominance of Jewish professionals, rather than workers. Jewish society, he argued, would not be healthy until the inverted pyramid was righted, and the majority of Jews became workers and peasants again. This, he held, could only be accomplished by Jews in their own country. Another Zionist thinker, [[A. D. Gordon]], was influenced by the ''[[völkisch]]'' ideas of European romantic nationalism, and proposed establishing a society of Jewish peasants. Gordon made a religion of work. These two figures, and others like them, motivated the establishment of the first Jewish collective settlement, or [[kibbutz]], [[Degania]], on the southern shore of the [[Sea of Galilee]], in 1909 (the same year that the city of [[Tel Aviv]] was established). Deganiah, and many other [[kibbutz]]im that were soon to follow, attempted to realise these thinkers' vision by creating a communal villages, where newly arrived European Jews would be taught agriculture and other manual skills.

| + | ===Zionism's victory and its aftermath=== |

| − | [[Image:Kibbutz_Degania_Alef.jpg|thumb|right|250px|[[Degania]], founded in 1909, was the first [[kibbutz]], the unique communal villages that were a key feature of [[Socialist Zionism]]. 1930s photograph.]]

| + | In 1947, the [[United Nations Special Committee on Palestine]] recommended the partition of western Palestine into a Jewish state, an Arab state, and a UN-controlled territory around [[Jerusalem]].<ref>''United Nations Special Committee on Palestine; Report the General,'' A/364, September 3, 1947.</ref> This partition plan was adopted on November 29, 1947, with [[United Nations General Assembly Resolution 181]], 33 votes in favor, 13 against, and 10 abstentions. The vote, which required a two-thirds majority, was a very dramatic affair and led to celebrations in the streets of Jewish cities.<ref>Youtube, [http://youtube.com/watch?v=rEGUPlhtMWQ Three minutes, 2000 years.] Retrieved July 29, 2008. </ref> |

| − | [[Image:Telaviv founding 1909.jpg|thumb|250px|[[Tel Aviv]], its name taken from a work by Theodor Herzl, was founded by Zionists on empty dunes north of Jaffa. This photograph is of the auction of the first lots in 1909.]] | |

| | | | |

| − | Another aspect of this strategy was the revival and fostering of an "indigenous" Jewish culture and the [[Hebrew language]]. One early Zionist thinker, Asher Ginsberg, better known by his pen name [[Ahad Ha'am]] ("One of the People") rejected what he regarded as the over-emphasis of political Zionism on statehood, at the expense of the revival of Hebrew culture. Ahad Ha'am recognized that the effort to achieve independence in Palestine would bring Jews into conflict with the native Palestinian Arab population, as well as with the Ottomans and European colonial powers then eying the country. Instead, he proposed that the emphasis of the Zionist movement shift to efforts to revive the Hebrew language and create a new culture, free from Diaspora influences, that would unite Jews and serve as a common denominator between diverse Jewish communities once independence was achieved.

| |

| | | | |

| − | The most prominent follower of this idea was [[Eliezer Ben-Yehuda]], a linguist intent on reviving Hebrew as a spoken language among Jews (''see [[History of the Hebrew language]]''). Most European Jews in the 19th century spoke [[Yiddish]], a language based on mediaeval German, but as of the 1880s, Ben Yehuda and his supporters began promoting the use and teaching of a modernised form of biblical Hebrew, which had not been a living language for nearly 2,000 years. Despite Herzl's efforts to have German proclaimed the official language of the Zionist movement, the use of Hebrew was adopted as official policy by Zionist organisations in Palestine, and served as an important unifying force among the Jewish settlers, many of whom also took new Hebrew names. | + | The Arab states, however, rejected the UN decision, demanding a single state with an Arab majority. Violence immediately exploded in Palestine between Jews and Arabs. On May 14, 1948, at the end of the [[British Mandate of Palestine|British mandate]], the Jewish Agency led by [[David Ben-Gurion]] declared the creation of the State of [[Israel]]. On the same day, the armies of [[Egypt]], [[Transjordan]], [[Iraq]], [[Syria]], [[Lebanon]], [[Yemen]], and [[Saudi Arabia]] joined forces against the newly created Israel. (Yemen and Saudi Arabia sent only small contingents of soldiers and Lebanese forces did not actually enter the country.) |

| | | | |

| − | The development of the first modern Hebrew-speaking city ([[Tel Aviv]]), the [[kibbutz]] movement, and other Jewish economic institutions, plus the use of Hebrew, began by the 1920s to lay the foundations of a new nationality, which would come into formal existence in 1948. Meanwhile, other cultural Zionists attempted to create new Jewish artforms, including graphic arts. ([[Boris Schatz]], a Bulgarian artist, founded the [[Bezalel Academy|Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design]] in Jerusalem in 1906.) Others, such as dancer and artist [[Baruch Agadati]], fostered popular festivals such as the Adloyada carnival on [[Purim]].

| + | During the following eight months, [[Israel Defense Forces|Israel forces]] defended the Jewish sector and conquered portions of the Arab sector, enlarging its portion to 78 percent of British mandatory Palestine. The conflict led to the relocation of more than 700,000 Arab Palestinians,<ref>''General Progress Report and Supplementary Report of the United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, Covering the period from 11 December 1949 to 23 October 1950,'' GA A/1367/Rev.1, October 23, 1950.</ref> of whom about 46,000 became [[Internally Displaced Palestinians|internally displaced persons]] in Israel. The war ended with the [[1949 Armistice Agreements]], which included new cease-fire lines, the so-called [[Green Line (Israel)|Green line]]. |

| | | | |

| − | ===British influence===

| + | Zionism had, thus, not only succeeded in its primary goal of establish a Jewish homeland, but had proven victorious in defending the Jewish state against the combined forces of its Arab neighbors. However, despite the armistice, the Arab nations continued to reject Israel's right to exist and demanded that it retreat to the 1947 partition lines. They sustained this demand until 1967, when the rest of western Palestine was conquered by Israel during the [[Six-Day War]], after which Arab states demanded that Israel only retreat to the 1949 cease fire line, the "borders" currently recognized by the international community. These borders are commonly referred as the "pre-1967 borders" or the "green line." The border with Egypt was legalized in the 1979 [[Egyptian-Israeli Peace Treaty]], and the border with Jordan in the 1994 [[Israel-Jordan Treaty of Peace]]. |

| | | | |

| − | Ideas of the restoration of the Jews in the Land of Israel entered the [[British Empire|British]] public discourse in the 19th century.<ref name=BritZion>[http://www.mideastweb.org/britzion.htm British Zionism - Support for Jewish Restoration] (mideastweb.org)</ref> Not all such attitudes were favorable towards the Jews; they were shaped in part by a variety of [[Protestant]] beliefs,<ref name=Cowen2002>[http://www.leaderu.com/common/british.html The Untold Story. The Role of Christian Zionists in the Establishment of Modern-day Israel] by Jamie Cowen (Leadership U), July 13, 2002</ref>

| + | After the creation of the State of Israel the WZO continued to exist as an organization dedicated to assisting and encouraging Jews to migrate to Israel, as well as providing political support for Israel. The major Israeli political parties remain avowedly Zionist, although the major Israeli political parties are sharply divided on many economic, political, religious, and foreign policy issues. Some anti-Zionist Israeli groups also exist, both Jewish and Arab. |

| − | or by a streak of [[philo-Semitism]] among the classically educated British elite,<ref name=Green2005>[http://www.historycooperative.org/journals/ahr/110.3/green.html Rethinking Sir Moses Montefiore: Religion, Nationhood, and International Philanthropy in the Nineteenth Century] by Abigail Green. (The American Historical Review. Vol. 110 No.3.) June 2005</ref>

| |

| − | or by hopes to extend the Empire. ''(See [[The Great Game]])''

| |

| | | | |

| − | At the urging of [[Lord Shaftesbury]], Britain established a consulate in Jerusalem in 1838, the first diplomatic appointment in the Land of Israel. In 1839, the [[Church of Scotland]] sent [[Andrew Bonar]] and [[Robert Murray M'Cheyne]] to report on the condition of the Jews in their land. Their report was widely published<ref>''A Narrative of a Mission of Inquiry to the Jews from the Church of Scotland in 1839'' (Edinburgh, 1842) ISBN 1-85792-258-1</ref> and was followed by a "Memorandum to Protestant Monarchs of Europe for the restoration of the Jews to Palestine."

| + | ==Types of Zionism== |

| − | In August 1840, ''The Times'' reported that the British government was considering Jewish restoration.<ref name=BritZion/>

| + | ===Labor Zionism=== |

| | + | Labor Zionism became the dominant trend in the Zionist movement in the early-mid twentieth century. Labor Zionists originated in Russia. They believed that centuries of being oppressed in antisemitic societies had reduced Jews to a meek, vulnerable, despairing existence which invited further [[antisemitism]]. In their view, the best protection for Jews was to become farmers, workers, and soldiers in a country of their own. Most Labor Zionists rejected religion as perpetuating a "[[diaspora]] mentality" among the Jewish people. After emigrating, they established rural communes in Israel called "[[kibbutzim]]," which became a mainstay of the Jewish population there in the early twentieth century. |

| | | | |

| − | Lord Lindsay wrote in 1847: "The soil of Palestine still enjoys her sabbaths, and only waits for the return of her banished children, and the application of industry, commensurate with her agricultural capabilities, to burst once more into universal luxuriance, and be all that she ever was in the days of Solomon."<ref>Crawford, A.W.C. (Lord Lindsay), ''Letters on Egypt, Edom and the Holy Land'', London, H. Colburn 1847, V II, p 71</ref>

| + | Major theoreticians of Labor Zionism included [[Moses Hess]], [[Nahum Syrkin]], [[Ber Borochov]], and [[Aaron David Gordon]]. Leading political figures in the movement included [[David Ben-Gurion]] and [[Berl Katznelson]]. Most Labor Zionists embraced Hebrew as the common Jewish tongue, rejecting Yiddish as part of the Jewish experience as second-class citizens of Europe. Because Labor Zionism was ardently secularist, the movement often had an antagonistic relationship with [[Orthodox Judaism]]. |

| − | The [[Treaty of Paris (1856)]] granted Jews and Christians the right to settle in Palestine and opened the doors for Jewish immigration.

| |

| − | In her 1876 novel ''[[Daniel Deronda]]'', [[George Eliot]] advocated "the restoration of a Jewish state planted in the old ground as a center of a national feeling, a source of dignifying protection, a special channel for special energies and an added voice in the councils of the world."

| |

| | | | |

| − | [[Benjamin Disraeli, 1st Earl of Beaconsfield|Benjamin Disraeli]] wrote in his article entitled "The Jewish Question is the Oriental Quest" (1877) that within fifty years a nation of one million Jews would reside in Palestine under the guidance of the British. [[Moses Montefiore]] visited the Land of Israel seven times and fostered its development.<ref name=Green2005/> | + | However, Labor Zionism became the dominant force in the political and economic life of the Jews in the Land of Israel during the [[British Mandate of Palestine]]—partly as a consequence of its role in organizing Jewish economic life through the [[Histadrut]] labor movement. Labor Zionism remained the dominant ideology of the political establishment in Israel until Israel's [[Israeli legislative election, 1977|1977 election]], when the [[Likud]] party emerged from a coalition of other Zionist factions in opposition to the Histadrut's socialist agenda. |

| | | | |

| − | [[Capitulations of the Ottoman Empire]] allowed the British to place missions in the region and to institute charitable projects such as hospitals, settlement colonies and exploratory surveys and by the end of the 19th century, British interest in the Middle East increased because it was considered essential to guard the route to [[India]]. | + | ===Liberal Zionism=== |

| | + | General Zionism (or Liberal Zionism) was the leading trend within the Zionist movement from the [[First Zionist Congress]], in 1897, until after the First World War. Many of the General Zionists were German or Russian liberals. However, following the Bolshevik revolution and the rise of [[fascism]], the liberals lost ground and the more militant Labor Zionists came to dominate the movement. Liberal Zionists identified with the European Jewish middle class from which many Zionist leaders, such as Herzl and [[Chaim Weizmann]], originated. They believed that a Jewish state could be accomplished through lobbying the Great Powers of Europe and influential circles in European society. General Zionism declined in the face of growing extremism and [[antisemitism]] in Central Europe, and because of the superior ability of labor Zionism to generate migration to Palestine. The trend re-emerged in the early 1970s, in oppositions to decades of Labor dominance in Israeli politics. |

| | | | |

| − | The Zionist leaders always saw [[United Kingdom|Britain]] as a key potential ally in the struggle for a Jewish homeland. Not only was Britain the world's greatest imperial power; it was also a country where Jews had lived for centuries in relative peace and security — among them influential political and cultural leaders such as Disraeli, Montefiore and [[Walter Rothschild, 2nd Baron Rothschild|Lord Rothschild]]. | + | ===Revisionist Zionism=== |

| | + | The Revisionist Zionists were a right wing Zionist group led by [[Ze'ev Jabotinsky]], who advocated pressing Britain to allow mass Jewish emigration and the formation of a Jewish Army in Palestine. The army would force the Arab population to accept mass Jewish migration and promote British interests in the region. Jabotinsky was a founder and leader of the clandestine Jewish armed organization [[Irgun]], noted for several infamous terrorist acts against the British. |

| | | | |

| − | [[Chaim Weizmann]]'s [[Royal Navy Cordite Factory, Holton Heath|invention of cordite]] was critical for the [[Allies of World War I]]. In his meetings with the British Prime Minister [[Lloyd George]] and the [[First Lord of the Admiralty]] [[Winston Churchill]], Weizmann, the leader of the Zionist movement since 1904, was able to advance the Zionist cause for which the war had created new prospects.<ref>{{PDFlink|[http://www.weizmann.ac.il/ICS/booklet/12/pdf/weizmann.pdf Moulder of Molecules: Maker of a Nation]|580 [[Kibibyte|KiB]]<!-- application/pdf, 594284 bytes —>}} by Michael Sutton (originally appeared in the December 2002 issue of ''Chemistry in Britain'' magazine)</ref> | + | Revisionist Zionism was detested by the Labor Zionist faction which accused the Revisionists as being influenced by [[fascism]]. After the [[1929 Palestine riots|1929 Arab riots]], the British banned Jabotinsky from entering Palestine. Revisionism was popular in Poland but lacked large support in Palestine. In 1935, the Revisionists left the [[Zionist Organization]] and formed an alternative, the [[New Zionist Organization]]. They rejoined the ZO in 1946. |

| | | | |

| − | This hope was realised in 1917, when the British Foreign Secretary, [[Arthur Balfour]], made his famous [[Balfour Declaration, 1917|Declaration]] in favour of "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people". The Declaration used the word "home" rather than "state," and specified that its establishment must not "prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine."

| + | ===Religious Zionism=== |

| | + | [[Image:Rabbi Dov Lior.JPG|thumb|250px|Rabbi [[Dov Lior]], leader of the religious Zionists of [[Hebron]], with students at dinner.]] |

| | + | In the 1920s and 1930s, a small but vocal group of religious Jews began to develop the concept of [[Religious Zionism]] under such leaders as Rabbi [[Abraham Isaac Kook]] and his son, Rabbi [[Zevi Judah Kook]]. They saw great religious and traditional value in many of Zionism's ideals, while rejecting its anti-religious undertones. They were also motivated by a concern that growing secularization of Zionism and antagonism towards it from Orthodox Jews would lead to a schism in the Jewish people. As such, they sought to forge a branch of [[Orthodox Judaism]] which would properly embrace Zionism's positive ideals while also serving as a bridge between Orthodox and secular Jews. The movement also established several religious [[kibbutzim]] in Israel. |

| | | | |

| − | == Jewish attitudes to Zionism before the founding of Israel ==

| + | After the [[Six Day War]], the Religious Zionism movement came to play a significant role in Israeli political life. It is a major component in the [[Israeli settler movement]], although not all Religious Zionists support the settlements. Those who do often justify their attitude on the basis of the biblical promises of God to [[Abraham]], in which the current Palestinian territories are described as belonging to Abraham's descendants through [[Isaac]], and specifically not through the descendants of [[Ishmael]] (Genesis 21:12), through whom many [[Muslims]] trace their ancestry. |

| − | {{Jews and Judaism}}

| |

| − | [[Image:Tarbut.jpg|thumb|left|Poster from the Zionist Tarbut schools of [[Poland]] in the 1930s. Zionist parties were very active in [[Poland|Polish]] politics. In the 1922 Polish elections, Zionists held 24 seats of a total of 35 Jewish parliament members.]] | |

| | | | |

| − | The chain of events between 1881 and 1945, beginning with waves of anti-Semitic [[pogrom]]s in [[Russia]] and [[Congress Poland|the Russian-controlled areas of Poland]], and culminating in [[the Holocaust]], converted the great majority of surviving Jews to the belief that a Jewish homeland was an urgent necessity, particularly given the large population of disenfranchised [[Jewish refugees]] after [[World War II]]. Most also became convinced that the Land of Israel was the only location that was both acceptable to all strands of Jewish thought and within the realms of practical possibility. This led to the great majority of Jews supporting the struggle between 1945 and 1948 to establish the State of Israel, though many did not condone violent tactics used by some Zionist groups.

| + | ==Critics of Zionism== |

| | + | There have been a number of critics of Zionism, including Jewish anti-Zionists, pro-Palestinian activists, academics, and politicians. Some of the most vocal critics of Zionism have been [[Arabs]], many of whom view Israel as occupying Arab land. Such critics generally opposed Israel's creation in 1948, and continue to criticize the Zionist movement which underlies it. These critics view the changes in demographic balance which accompanied the creation of Israel, including the displacement of some 700,000 Arab [[Palestinian refugee|refugees]], and the accompanying violence, the inevitable consequences of Zionism and the concept of a [[Jewish State]]. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Opposition or ambivalence===

| + | While most Jewish groups are pro-Zionist, some ''[[Haredi Judaism|haredi]]'' Jewish communities (most vocally the [[Satmar]] Hasidim and the small [[Neturei Karta]] group), oppose Zionism on religious grounds and denounce all cooperation with Zionists. The primary ''haredi'' anti-Zionist work is ''[[Vayoel Moshe]]'' by Satmar [[Rebbe]] [[Joel Teitelbaum]]. Some other haredi groups support Israeli political parties which are also anti-Zionist but work through the political structure in order that their interests not be neglected. |

| − | {{main|Anti-Zionism#Jewish anti-Zionism}}

| |

| | | | |

| − | Initially, support for political Zionism was not a mainstream position in the Jewish communities scattered around the world. The secular, socialist language used by many pioneer Zionists was contrary to the outlook of most religious Jewish communities, and many religious organizations opposed it, both on the grounds that it was a secular movement, and on the grounds that any attempt to re-establish Jewish rule in Israel by [[Agency (philosophy)|human agency]] was blasphemous, since (in their view) only the [[Jewish eschatology|Messiah]] could accomplish this.<ref>"Most Orthodox Jews originally rejected Zionism because they believed the Jews must await the Messiah to restore them to nationhood." ''Settings of Silver: An Introduction to Judaism. Stephen M. Wylen, 2000, Paulist Press, page 356</ref>

| + | The non-Zionist Israeli [[canaanites (movement)|Canaanite]] movement led by poet [[Yonatan Ratosh]], in the 1930s and 1940s, argued that "Israeli" should be a new pan-ethnic [[nationality]]. A related modern movement is known as [[post-Zionism]], which asserts that Israel should abandon the concept of a Jewish state. Some critics of Zionism have accused it of racism, an accusation endorsed by the 1975 [[United Nations General Assembly Resolution 3379]], which was revoked in 1991. There are also individual Jews who have taken strong public stands against various aspects of Israeli policy, but who resist the claim that they oppose Zionism itself. The most famous of is the linguist and left-wing political activist [[Noam Chomsky]]. |

| | | | |

| − | While traditional [[Judaism|Jewish belief]] held that the Land of Israel was given to the ancient [[Israelite]]s by [[God]], and that therefore the right of the Jews to that land was permanent and inalienable, most [[Orthodox Judaism|Orthodox]] groups held that the Messiah must appear before Israel could return to Jewish control. Prior to [[the Holocaust]], [[Reform Judaism]] rejected Zionism.{<ref>"Reform Jews originally rejected Zionism as inconsistent with the acceptance of Jewish citizenship in the Diaspora." ''Settings of Silver: An Introduction to Judaism. Stephen M. Wylen, 2000, Paulist Press, page 356</ref>

| + | ==Christian Zionism== |

| | + | In addition to Jewish Zionists, a small number of [[Christian Zionism|Christian Zionists]] have been active from the early days of the Zionist movement. Throughout the entire nineteenth and early twentieth century, the return of the Jews to the Holy Land was widely supported by such eminent figures in the Christian world. |

| | | | |

| − | When the Balfour Declaration was issued in 1917, [[Edwin Montagu]], the only Jew in the British Cabinet, "was passionately opposed to the declaration on the grounds that (a) it was a capitulation to anti-Semitic bigotry, with its suggestion that Palestine was the natural destination of the Jews, and that (b) it would be a grave cause of alarm to the Muslim world."<ref>Hitchens, "Love, Poverty, and War" 327</ref>

| + | Evangelical Christians have a long history of supporting Zionism. Famous evangelical supporters of Israel include British Prime Ministers [[David Lloyd George]] and [[Arthur Balfour]], and U.S. President [[Woodrow Wilson]]. Christian Zionism strengthened significantly after the 1967 [[Six-Day War]], and many [[Dispensationalism|dispensationalist]] Christians, especially in the United States, now strongly support Zionism, seeing the establishment of the State of Israel as the fulfillment of biblical [[prophecy]]. |

| | | | |

| − | ===Support=== | + | ==See also== |

| − | The 1911 edition of the [[Jewish Encyclopedia]] evidenced the movement's growing popularity: "there is hardly a nook or corner of the Jewish world in which Zionistic societies are not to be found."<ref>[http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com/view.jsp?artid=132&letter=Z&search=Zionism Zionism article (section ''Wide Spread of Zionism'')] by Richard Gottheil in the [[Jewish Encyclopedia]], 1911</ref>

| + | *[[Israel]] |

| − | | + | *[[Theodor Herzl]] |

| − | {{main|Religious Zionism}}

| + | *[[Haim Weizman]] |

| − | In the 1920s and 1930s, a small but vocal group of religious Jews began to develop the concept of [[Religious Zionism]] under such leaders as Rabbi [[Abraham Isaac Kook]] (the Chief Rabbi of Palestine) and his son Zevi Judah, and gained substantial following during the latter half of the 20th century. Only the desperate circumstances of the 1930s and 1940s converted most (though not all) of these communities to Zionism. By 1940, there were 171,000 members of Zionist organizations, and by 1942, 80% of American Jews surveyed agreed that a homeland in Palestine was required.<ref>Stork and Rose, 1974</ref>

| + | *[[David Ben-Gurion]] |

| − | | |

| − | ==International reactions to Zionism==

| |

| − | [[Napoleon and the Jews#Napoleon and a Jewish state in Palestine|Napoleon suggested]] the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine as early as 1799.<ref>[[Shlomo Avineri|Avineri, Shlomo]], ''The Making of Modern Zionism: Intellectual Origins of the Jewish State'', pp.45, Basic Books (1981), ISBN 0-465-04328-3</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Throughout the entire 19th century and early 20th century, the return of the Jews to the Holy Land was widely supported by such eminent figures as [[Queen Victoria]], [[King Edward VII]], [[John Adams]], the second President of the [[United States]], [[Jan Smuts|General Smuts]] of [[South Africa]], [[Tomáš Masaryk|President Masaryk]] of [[Czechoslovakia]], British Prime Ministers Lloyd George and Arthur Balfour, President [[Woodrow Wilson]], [[Benedetto Croce]], [[Italy|Italian]] philosopher and historian, [[Henry Dunant]], founder of the [[Red Cross]] and author of the [[Geneva Conventions]], [[Fridtjof Nansen]], [[Norway|Norwegian]] scientist and humanitarian. The [[France|French]] government through Minister M. Cambon formally committed itself to “the renaissance of the Jewish nationality in that Land from which the people of Israel were exiled so many centuries ago". Even in faraway [[China]], Wang, Minister of Foreign Affairs, declared that "the Nationalist government is in full sympathy with the Jewish people in their desire to establish a country for themselves."<ref> Palestine: The Original Sin , Meir Abelson [http://www.acpr.org.il/ENGLISH-NATIV/issue1/Abelson-1.htm] </ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | In 1873, Shah Nasr-ed-Din met with British Jewish leaders, including Sir [[Moses Montefiore]], during his journey to Europe. At that time, the Persian leader suggested that the Jews buy land and establish a state for the Jewish people.<ref>[http://www.worldjewishcongress.org/communities/mideast/comm_iran.html]</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | King [[Faisal I of Iraq]] supported the idea of Zionism and signed the [[Faisal-Weizmann Agreement]] in 1919. He wrote: "We [[Arabs]], especially the educated among us, look with the deepest sympathy on the Zionist movement. Our delegation here in Paris is fully acquainted with the proposals submitted yesterday to the Zionist organization to the Peace Conference, and we regard them as moderate and proper."

| |

| − | | |

| − | Both the [[League of Nations]]' [[1922]] [[Palestine Mandate]] and the [[1947 UN Partition Plan]] broadly endorsed the aim of Zionism. The latter was a rare instance of concurrence between the United States and the Soviet Union during the [[Cold War]], although [[Harry Truman]]'s State Department, led by [[George Marshall]], vehemently opposed the formation of the state of Israel.<ref> David McCullough, ''Truman'', Simon and Schuster, 1992, pp. 614-620</ref> Only Truman's personal insistence overcame Marshall's intense opposition, which was based on strategic concerns for the stability of the region.<ref> Ibid. </ref> Marshall's opposition was recounted in detail by Truman's aide [[Clark Clifford]], who led the internal campaign to recognize a new Jewish state.<ref> Clark Clifford, with Richard Holbrooke, ''Counsel to the President'', Random House, 1991.</ref>

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==Zionism and the Arabs==

| |

| − | {{Unreferencedsect|date=May 2007}}

| |

| − | The Jews who already lived in the region of [[Palestine]] had a long and complex [[History of the Jews under Muslim rule|history]] of interaction with their Muslim neighbours and rulers, which was complicated by the relationship between [[Islam and Judaism]]. Outside of [[Jerusalem]], [[Safed]], and [[Tiberias]], [[Arab]]s and/or [[Muslim]]s constituted the overwhelming majority of the population. The early Zionists were well aware of this, but claimed that the inhabitants could only benefit from Jewish immigration. They also were inclined to settle in uninhabited areas, such as the coastal plain and the [[Jezreel Valley]], thus avoiding conflict with the Arabs. Within Zionist literature, the Arab presence was largely ignored, as in the famous slogan "A land without a people for a people without a land." This slogan is often attributed to [[Israel Zangwill]], but its original form, "A country without a nation for a nation without a country," was penned by [[Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury|Lord Shaftesbury]].<ref name=BritZion/>

| |

| − | | |

| − | Though there had already been Arab protests to the Ottoman authorities in the 1880s against land sales to foreign Jews, the most serious opposition began in the 1890s after the full scope of the Zionist enterprise became known. This opposition did not arise out of Palestinian nationalism, which was in its infancy at the time, but out of a sense of threat to the livelihood of the Arabs. This sense was heightened in the early years of the 20th century by the Zionist attempts to develop an economy from which Arab people were largely excluded, such as the "Hebrew labor" movement that campaigned against the employment of Arabs. The severing of Palestine from the rest of the Arab world in 1918 and the [[Balfour Declaration, 1917|Balfour Declaration]] were seen by the Arabs as proof that their fears were coming to fruition.

| |

| − | [[Image:Zeev Jabotinsky.jpg|thumb|180px|[[Zeev Jabotinsky]]]]

| |

| − | | |

| − | A wide range of opinion could be found among Zionist leaders after 1920. However, the division between these camps did not match the main threads in Zionist politics so cleanly as is often portrayed. To take an example, the leader of the [[Revisionist Zionism|Revisionist Zionists]], [[Vladimir Jabotinsky]], is often presented as having had an extreme pro-expulsion view but the proofs offered for this are rather thin. According to Jabotinsky's ''Iron Wall'' (1923), an agreement with the Arabs was impossible, since they

| |

| − | <blockquote>

| |

| − | look upon Palestine with the same instinctive love and true fervor that any [[Aztec]] looked upon his [[Mexico]] or any [[Sioux]] looked upon his prairie. To think that the Arabs will voluntarily consent to the realization of Zionism in return for the cultural and economic benefits we can bestow on them is infantile.

| |

| − | </blockquote>

| |

| − | | |

| − | The solution, according to Jabotinsky, was not expulsion (which he was "prepared to swear, for us and our descendants, that we will never [do]") but to impose the Jewish presence on the Arabs by force of arms until eventually they came to accept it. Only late in his life did Jabotinsky speak of the desirability of Arab emigration though still without unequivocally advocating an expulsion policy. After the [[World Zionist Organization]] rejected Jabotinsky's proposals, he resigned from the organization and founded the [[New Zionist Organization]] in 1933 to promote his views and work independently for immigration and the establishment of a state. The NZO rejoined the WZO in 1951.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The situation with socialist Zionists such as [[David Ben-Gurion]] was also ambiguous. In public Ben-Gurion upheld the official position of his party that denied the necessity of force in achieving Zionist goals. The argument was based on the denial of a unique Palestinian identity coupled with the belief that eventually the Arabs would realise that Zionism was to their advantage. The British plan was soon shelved, but the idea of a Jewish state with a minimal population of Arabs remained an important thread in Labour Zionist thought throughout the remaining period until the creation of [[Israel]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | The attitude of the Zionist leaders towards the Arab population of Palestine in the lead-up to the 1948 conflict is one of the most hotly debated issues in Zionist history.

| |

| − | {{See also|1936-1939 Arab revolt in Palestine|Israel-Palestinian conflict|Palestinian exodus}}

| |

| − | | |

| − | ==The struggle for Palestine==

| |

| − | ===Before the Holocaust===

| |

| − | | |

| − | With the defeat and dismantling of the Ottoman Empire in 1918, and the establishment of the [[British Mandate of Palestine|British Mandate]] over Palestine by the [[League of Nations]] in 1922, the Zionist movement entered a new phase of activity. Its priorities were the escalation of Jewish settlement in Palestine, the building of the institutional foundations of a Jewish state, raising funds for these purposes, and persuading — or forcing — the British authorities not to take any steps which would lead to Palestine moving towards independence as an Arab-majority state. The 1920s did see a steady growth in the Jewish population and the construction of state-like Jewish institutions, but also saw the emergence of Palestinian Arab nationalism and growing resistance to Jewish immigration.

| |

| − | | |

| − | International Jewish opinion remained divided on the merits of the Zionist project. While many Jews in Europe and the United States argued that a Jewish homeland was not needed because Jews were able to live in the democratic countries of the West as equal citizens, others supported Zionism.

| |

| − | | |

| − | [[Albert Einstein]] was one of the prominent supporters of Zionism, and was active in the establishment of the [[Hebrew University of Jerusalem]], which published in 1930 a volume titled ''About Zionism: Speeches and Lectures by Professor Albert Einstein'', and to which Einstein bequeathed his papers. However, he opposed nationalism and expressed skepticism about whether a Jewish nation-state was the best solution. He said: "I am afraid of the inner damage Judaism will sustain, especially from the development of a narrow nationalism within our own ranks."

| |

| − | | |

| − | Many Jews who embraced [[socialism]] and [[proletarian internationalism]] opposed Zionism as a form of [[bourgeois nationalism]]. The [[General Jewish Labor Union]] (Bund), which represented socialist Jews in eastern Europe, was anti-Zionist. Some Jewish factions tried to blend [[Jewish Autonomism]] with Zionism, favoring Jewish self-rule in the diaspora until diaspora Jews make aliyah.

| |

| − | | |

| − | The Communist parties, which attracted substantial Jewish support during the 1920s and 1930s, were even more vigorously internationalist and therefore anti-Zionist, if one defines Zionism as the advocacy of a Jewish homeland in Palestine. During this time the Soviet [[OZET]]/[[Komzet]] actively promoted an alternative Jewish homeland — the [[Jewish Autonomous Oblast]] with its capital in [[Birobidzhan]] set up in the [[Russian Far East]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | At the other extreme, some American Jews went so far as to say that the United States ''was'' Zion, and the successful absorption of two million Jewish immigrants in the 30 years before [[World War I]] lent force to this argument. Some American Jewish socialists supported the Birobidzhan experiment, and a few even migrated there during the [[Great Depression]].

| |

| − | | |

| − | ===Rise of the Nazis in Germany===

| |

| − | The rise to power of [[Adolf Hitler]] in Germany in 1933 produced a powerful new impetus for Zionism. Not only did it create a flood of [[Jewish refugees]] but it undermined the faith of Jews that they could live in security as minorities in non-Jewish societies. Jewish opinion began to shift in favour of Zionism, and pressure for more [[Aliyah#Fifth Aliyah (1929-1939)|Jewish immigration to Palestine]] increased. But the more Jews settled in Palestine, the more aroused local Arab opinion became, and the more difficult the situation became in Palestine.

| |

| − | | |

| − | In 1936 serious Arab rioting broke out, and in response the British authorities held the unsuccessful [[St. James Conference]] and issued the [[White Paper of 1939|MacDonald White Paper of 1939]], severely restricting further Jewish immigration.

| |

| − | | |