Difference between revisions of "Toxin" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (16 intermediate revisions by 6 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

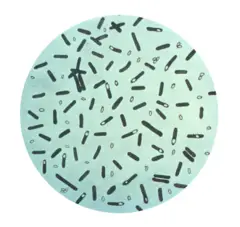

| + | [[Image:Clostridium botulinum_01.png|thumb|right|240px|''Clostridium botulinum'', a bacteria that produces botulinum toxin, a neurotoxin [[protein]] that to humans is one of the most [[poison]]ous naturally-occurring substances in the world]] | ||

| + | A '''toxin''' is a chemical substance that is capable of causing [[injury]], illness, or death to an organism ([[poison]]) and that is produced by living [[cell (biology)|cells]] or another organism. The term sometimes is used in a broader sense to refer to any substance that is poisonous to an organism, but generally the usage is limited to poisons produced via some biological function in nature, such as the [[bacterium|bacteria]]l [[protein]]s that cause [[tetanus]] and [[botulism]]. While the term is especially applied to substances of bacterial origin, many diverse taxa produce toxins, including [[dinoflagellate]]s, [[fungus|fungi]], [[plant]]s, and [[animal]]s. | ||

| + | Toxins are nearly always [[protein]]s that are capable of causing harm on contact or absorption with body [[tissue]]s by interacting with biological [[macromolecule]]s such as [[enzyme]]s or cellular receptors. Toxins vary greatly in their severity, ranging from usually minor and acute (as in a [[bee]] sting) to almost immediately deadly (as in [[botulinum toxin]]). | ||

| + | Biotoxins vary greatly in purpose and mechanism, and they can be highly complex (the [[venom]] of the cone snail contains dozens of small proteins, each targeting a specific nerve channel or receptor), or a single, relatively small protein. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Human creativity has resulted in understanding about toxins and their mechanisms, and this knowledge has been employed in making effective insecticides, to improve the quality of human life, and in making vaccines and antidotes (such as antivenom to snake toxins). On the other hand, human creativity also has used this knowledge to create nerve agents designed for [[biological warfare]] and biological [[terrorism]]. For example, in 2001, powdered preparations of ''Bacillus anthracis'' spores were delivered to targets in the [[United States]] through the [[postal system|mail]] (Lerner and Lerner 2004). Inhaling the weaponized spores can causes a form of quickly developing [[anthrax]] that is almost always fatal if not treated (Lerner and Lerner 2004). Ricin, a toxin produced from the castor bean, has long been used as a weapon of terrorism, and is one for which there is no [[vaccine]] or [[antidote]] (Lerner and Lerner 2004). | ||

| + | ==Functions of toxins== | ||

| + | Biotoxins in nature have two primary functions: | ||

| + | *Predation or invasion of a host ([[bacterium]], [[spider]], [[snake]], [[scorpion]], [[jellyfish]], [[wasp]]) | ||

| + | *Defense ([[bee]], [[poison dart frog]], [[deadly nightshade]], [[honeybee]], [[wasp]]) | ||

| + | For example, a toxin may be used in assisting bacterial invasion of a host's cells or tissues or to combat the defense system of the host. A spider may use toxin to paralyze a larger prey, or a snake may use to subdue its prey. On the other hand, a honeybee sting, while of little benefit to the honeybee itself (which usually dies as a result of part of the abdomen ripping lose with the stinger), can help in discouraging predation on the bees or their hive products. | ||

| + | Sometimes, however, action of a toxin on an organism may not correlate to any direct benefit to the organism producing the toxin, but be accidental damage. | ||

| + | ==Types of organisms producing toxins== | ||

| − | + | Numerous types of organisms produce toxins. Some well-known examples are listed below. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Bacteria=== | ===Bacteria=== | ||

| − | + | The term toxin is used especially in terms of poisonous substances produced by [[bacteria]]. Examples include [[cholera]] toxin from ''Vibrio cholera'', [[tetanus]] toxin from ''Clostridium tetani'', [[botulism]] toxin from ''Clostridium botulinum'', and [[anthrax]] toxin from ''Bacillus anthracis''. | |

| − | + | Bacterial toxins can damage the cell wall of the host (e.g., alpha toxin of ''Clostridium perfringens''), stop the manufacture of [[protein]] in host cells or degrade the proteins (e.g., exotoxin A of ''Pseudomonas aeruginosa'' or the protein degrading toxins of ''Clostridium botulinum''), or stimulate an [[immune system|immune response]] in the host that is so strong as to damage the host (e.g., three different toxins of ''Staphylococcus aureus'' resulting in toxic shock syndrome) (Lerner and Lerner 2004). | |

| + | Bacterial toxins are classified as either exotoxins or endotoxins. An ''exotoxin'' is a soluble [[protein]] excreted by a [[microorganism]], including [[bacterium|bacteria]], [[fungi]], [[algae]], and [[protozoa]]. An exotoxin can cause damage to the host by destroying cells or disrupting normal [[metabolism|cellular metabolism]]. ''Endotoxins'' are potentially toxic [[nature|natural]] compounds found inside [[pathogen]]s such as bacteria. Classically, an endotoxin is a toxin that, unlike an exotoxin, is not secreted in soluble form, but is a structural component in bacteria that is released mainly when bacteria are [[lysis|lysed]]. Of course, exotoxins also may be released if the cell is lysed. | ||

| − | + | Both [[bacteria|gram positive]] and gram negative bacteria produce exotoxins, while endotoxins mainly are produced by gram negative bacteria. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ====Types of exotoxins==== | |

| + | Exotoxins can be categorized by their mode of action on target cells. | ||

| + | * Type I toxins: Toxins that act on the cell surface. Type I toxins bind to a receptor on the cell surface and stimulate intracellular signaling pathways. For example, "superantigens" produced by the strains of ''[[Staphylococcus aureus]]'' and ''[[Streptococcus pyogenes]]'' cause [[toxic shock syndrome]]. | ||

| + | * Type II toxins: Membrane damaging toxins. These toxins are designed primarily to disrupt the [[cell membrane|cellular membrane]]. Many type II exotoxins have [[hemolysin]] activity, which causes red blood cells to lyse ''in vitro''. | ||

| + | * Type III toxins: Intracellular toxins. Intracellular toxins must be able to gain access to the [[cytoplasm]] of the target cell to exert their effects. Some bacteria deliver toxins directly from their cytoplasm to the cytoplasm of the target cell through a needle-like structure. The effector proteins injected by the type III [[secretion]] apparatus of ''[[Yersinia]]'' into target cells are one example. Another well-known group of intracellular toxins is the AB toxins. The 'B'-subunit attaches to target regions on cell membranes, allowing the the 'A'-subunit to enter through the membrane and stimulate [[enzyme|enzymatic]] actions that affects internal cellular bio-mechanisms. The structure of these toxins allows for the development of specific [[vaccine]]s and treatments. For example, certain compounds can be attached to the B unit, which the body learns to recognize, and which elicits an [[immune system|immune response]]. This allows the body to detect the harmful toxin if it is encountered later, and to eliminate it before it can cause harm to the host. Toxins of this type include [[cholera toxin]], [[pertussis toxin]], [[Shiga toxin]], and heat-labile [[enterotoxin]] from ''[[E. coli]]''. | ||

| + | * Toxins that damage the extracellular matrix. These toxins allow the further spread of bacteria and consequently deeper tissue infections. Examples are [[hyaluronidase]] and [[collagenase]]. | ||

| − | + | Exotoxins are susceptible to [[antibody|antibodies]] produced by the [[immune system]], but many exotoxins are so toxic that they may be fatal to the host before the immune system has a chance to mount defenses against it. | |

| − | == | + | ====Endotoxin examples==== |

| − | |||

| − | + | The prototypical examples of endotoxin are [[lipopolysaccharide]] (LPS) or lipo-oligo-saccharide (LOS) found in the outer membrane of various [[bacteria|gram-negative bacteria]]. The term LPS is often used interchangeably with endotoxin, owing to its historical discovery. In the 1800s, it became understood that bacteria could secrete toxins into their environment, which became broadly known as "exotoxin." The term endotoxin came from the discovery that portions of gram-negative bacteria themselves can cause [[toxicity]], hence the name endotoxin. Studies of endotoxin over the next 50 years revealed that the effects of "endotoxin" was in fact due to lipopolysaccharide. | |

| − | The | + | LPS consist of a [[polysaccharide]] ([[sugar]]) chain and a [[lipid]] [[moiety]], known as lipid A, which is responsible for the toxic effects. The polysaccharide chain is highly variable among different bacteria. Humans are able to produce [[antibody|antibodies]] to endotoxins after exposure but these are generally directed at the polysaccharide chain and do not protect against a wide variety of endotoxins. |

| − | + | There are, however, endotoxins other than LPS. For example, delta endotoxin of ''[[Bacillus thuringiensis]]'' makes [[crystal]]-like inclusion bodies next to the [[endospore]] inside the bacteria. It is toxic to larvae of [[insect]]s feeding on plants, but is harmless to humans (as we do not possess the enzymes and receptors necessary for its processing followed by toxicity). | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | The only known gram positive bacteria that produces endotoxin is ''Listeria monocytogenes''. | |

| − | + | ===Dinoflagellates=== | |

| − | + | Dinoflagellates can produce toxic substances of danger to humans. For instance, one should avoid consuming [[mussel]]s along the west coast of the United States during the warmer months. This is because dinoflagellates create elevated levels of toxins in the water that do not harm the mussels, but if consumed by humans can bring on illness. Usually the United States government monitors the levels of toxins throughout the year at fishing sites. | |

| − | === | + | ===Fungi=== |

| − | |||

| − | + | Two species of [[mold]]—''Aspergillus flavus'' and ''Aspergillus parasiticus''—produce aflatoxin, which can contaminate [[potato]]es afflicted by the mold (Lerner and Lerner 2004). This can lead to serious and even fatal illness. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Plants=== | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Many plants produce toxins designed to protect against [[insect]]s and other animal consumers, or [[fungi]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The [[root]]s of the [[tobacco]] plant produce a substance called [[nicotine]], which is stored mainly in the [[leaf|leaves]]. Nicotine is a powerful poison and seems to benefit the plant by protecting it from [[insect]]s, working by attacking the junctions between the insects' nerve cells (Stuart 2004). Tobacco leaves are sometimes soaked or boiled and the water sprayed on other plants as an organic insecticide. Nicotine is also a deadly poison to [[human being|humans]]. Two to four drops (pure nicotine is an oily liquid) are a fatal dose for an adult. Smoking and chewing tobacco results in a much smaller dose; however, people have died as a result of mistaking wild tobacco for an edible herb and boiling and eating a large quantity (IPCS 2006). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Poison ivy, poison hemlock, and nightshade are other plants that produce toxins that work against humans. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Ricin is found in the castor bean plant, and is the third most deadly toxin to humans known, after the toxins produced by ''Clostridium botulinum'' and ''Clostridium tetani'' (Lerner and Lerner 2004). There is no known vaccine or antidote, and if exposed symptoms can appear within hours ([[nausea]], muscle spasms, severe [[lung]] damage, and convulsion) and death from pulmonary failure within three days (Lerner and Lerner 2004). | |

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ===Animals=== |

| − | |||

| − | + | Many animals use toxins for predation or defense. Well known examples include [[pit_viper|pit vipers]], such as [[rattlesnake]]s, that possess hemotoxins that target and destroy [[red blood cell]]s and are transmitted through the bloodstream; the brown recluse or "fiddle back" [[spider]] that uses necrotoxins that cause death in the cells they encounter and destroy all types of [[tissue]]s; and the [[Black widow spider|black widow]] spider, most [[scorpion]]s, the box [[jellyfish]], [[Elapidae|elapid]] [[snake]]s, and the cone snail that use neurotoxins that primarily affect the [[nervous system]] of animals. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The puffer fish produces the deadly toxin ''tetrodotoxin'' in its [[liver]] and ovaries; it blocks nerve conduction (Blakemore and Jennett 2001). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Terminology: Toxin, poison, venom== | |

| − | + | The term toxin comes from the Greek {{polytonic|τοξικόν}} ''toxikon'', meaning "(poison) for use on arrows." In the context of [[biology]], '''poisons''' are substances that can cause damage, [[illness]], or [[death]] to [[organism]]s, usually by [[chemical reaction]] or other [[activity]] on the [[molecular]] scale, when a sufficient quantity is absorbed by an organism. | |

| − | In [[ | ||

| − | + | '''Toxin''' is a subcategory of poison, referring to a substance produced by a living organism. However, when used non-technically, the term "toxin" is often applied to any poisonous substance. Many non-technical and lifestyle journalists also follow this usage to refer to toxic substances in general, though some specialist journalists maintain the distinction that toxins are only those produced by living organisms. In the context of [[alternative medicine]] the term toxin often is used nonspecifically as well to refer to any substance claimed to cause ill health, ranging anywhere from trace amounts of pesticides to common [[food]] items like refined [[sugar]] or additives like [[artificial sweetener]]s and [[Monosodium glutamate|MSG]]. | |

| − | + | In pop [[psychology]], the term toxin sometimes is used to describe things that have an adverse effect on psychological health, such as a "toxic relationship," "toxic work environment," or "toxic shame." | |

| − | + | '''Venoms''' usually are defined as biologic toxins that are delivered subcutaneously, such as injected by a bite or sting, to cause their effect. In normal usage, a poisonous organism is one that is harmful to consume, but a venomous organism uses poison to defend itself while still alive. A single organism can be both venomous and poisonous. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The derivative forms "toxic" and "poisonous" are synonymous. | |

| − | A | + | A weakened version of a toxin is called a '''toxoid''' (Lerner and Lerner 2004). Toxids have been treated chemically or by heat to limit their toxicity while still allowing them to stimulate the formation of [[antibody|antibodies]]. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * [http:// | + | * Blakemore, C., and S. Jennett. 2001. ''The Oxford Companion to the Body''. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019852403X |

| − | * Sofer, G. | + | * International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS). 2006. ''[http://www.inchem.org/documents/pims/plant/nicotab.htm Nicotiana tabacum''.] International Programme on Chemical Safety. Retrieved August 24, 2007. |

| + | * Lerner, K. L., and B. W. Lerner. 2004. ''Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence, and Security''. Detroit, MI: Thomson/Gale. ISBN 0787675466 | ||

| + | * Ryan, K. J., and C. G. Ray, eds. 2004. ''Sherris Medical Microbiology'', 4th ed. McGraw Hill. ISBN 0838585299 | ||

| + | * Sofer, G., and L. Hagel. 1997. ''Handbook of Process Chromatography: A Guide to Optimization, Scale-up, and Validation.'' Academic Press. ISBN 012654266X | ||

| + | * Stuart, D. 2004 ''Dangerous Garden''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 067401104 | ||

| + | * Todar, K. 2002. [http://textbookofbacteriology.net/endotoxin.html Mechanisms of Bacterial Pathogenicity: Endotoxins.] ''Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology''. Retrieved August 24, 2007. | ||

| + | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved May 1, 2023. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

*[http://www.toxicology.org Society of Toxicology] | *[http://www.toxicology.org Society of Toxicology] | ||

*[http://www.jvat.org.br The Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases] | *[http://www.jvat.org.br The Journal of Venomous Animals and Toxins including Tropical Diseases] | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|Toxin|138184566|Exotoxin|141914013|Poison|139493579|Endotoxin|138464121}} | {{credit|Toxin|138184566|Exotoxin|141914013|Poison|139493579|Endotoxin|138464121}} | ||

| − | [[Caregory: | + | [[Caregory:Life sciences]] |

Latest revision as of 04:49, 1 May 2023

A toxin is a chemical substance that is capable of causing injury, illness, or death to an organism (poison) and that is produced by living cells or another organism. The term sometimes is used in a broader sense to refer to any substance that is poisonous to an organism, but generally the usage is limited to poisons produced via some biological function in nature, such as the bacterial proteins that cause tetanus and botulism. While the term is especially applied to substances of bacterial origin, many diverse taxa produce toxins, including dinoflagellates, fungi, plants, and animals.

Toxins are nearly always proteins that are capable of causing harm on contact or absorption with body tissues by interacting with biological macromolecules such as enzymes or cellular receptors. Toxins vary greatly in their severity, ranging from usually minor and acute (as in a bee sting) to almost immediately deadly (as in botulinum toxin).

Biotoxins vary greatly in purpose and mechanism, and they can be highly complex (the venom of the cone snail contains dozens of small proteins, each targeting a specific nerve channel or receptor), or a single, relatively small protein.

Human creativity has resulted in understanding about toxins and their mechanisms, and this knowledge has been employed in making effective insecticides, to improve the quality of human life, and in making vaccines and antidotes (such as antivenom to snake toxins). On the other hand, human creativity also has used this knowledge to create nerve agents designed for biological warfare and biological terrorism. For example, in 2001, powdered preparations of Bacillus anthracis spores were delivered to targets in the United States through the mail (Lerner and Lerner 2004). Inhaling the weaponized spores can causes a form of quickly developing anthrax that is almost always fatal if not treated (Lerner and Lerner 2004). Ricin, a toxin produced from the castor bean, has long been used as a weapon of terrorism, and is one for which there is no vaccine or antidote (Lerner and Lerner 2004).

Functions of toxins

Biotoxins in nature have two primary functions:

- Predation or invasion of a host (bacterium, spider, snake, scorpion, jellyfish, wasp)

- Defense (bee, poison dart frog, deadly nightshade, honeybee, wasp)

For example, a toxin may be used in assisting bacterial invasion of a host's cells or tissues or to combat the defense system of the host. A spider may use toxin to paralyze a larger prey, or a snake may use to subdue its prey. On the other hand, a honeybee sting, while of little benefit to the honeybee itself (which usually dies as a result of part of the abdomen ripping lose with the stinger), can help in discouraging predation on the bees or their hive products.

Sometimes, however, action of a toxin on an organism may not correlate to any direct benefit to the organism producing the toxin, but be accidental damage.

Types of organisms producing toxins

Numerous types of organisms produce toxins. Some well-known examples are listed below.

Bacteria

The term toxin is used especially in terms of poisonous substances produced by bacteria. Examples include cholera toxin from Vibrio cholera, tetanus toxin from Clostridium tetani, botulism toxin from Clostridium botulinum, and anthrax toxin from Bacillus anthracis.

Bacterial toxins can damage the cell wall of the host (e.g., alpha toxin of Clostridium perfringens), stop the manufacture of protein in host cells or degrade the proteins (e.g., exotoxin A of Pseudomonas aeruginosa or the protein degrading toxins of Clostridium botulinum), or stimulate an immune response in the host that is so strong as to damage the host (e.g., three different toxins of Staphylococcus aureus resulting in toxic shock syndrome) (Lerner and Lerner 2004).

Bacterial toxins are classified as either exotoxins or endotoxins. An exotoxin is a soluble protein excreted by a microorganism, including bacteria, fungi, algae, and protozoa. An exotoxin can cause damage to the host by destroying cells or disrupting normal cellular metabolism. Endotoxins are potentially toxic natural compounds found inside pathogens such as bacteria. Classically, an endotoxin is a toxin that, unlike an exotoxin, is not secreted in soluble form, but is a structural component in bacteria that is released mainly when bacteria are lysed. Of course, exotoxins also may be released if the cell is lysed.

Both gram positive and gram negative bacteria produce exotoxins, while endotoxins mainly are produced by gram negative bacteria.

Types of exotoxins

Exotoxins can be categorized by their mode of action on target cells.

- Type I toxins: Toxins that act on the cell surface. Type I toxins bind to a receptor on the cell surface and stimulate intracellular signaling pathways. For example, "superantigens" produced by the strains of Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pyogenes cause toxic shock syndrome.

- Type II toxins: Membrane damaging toxins. These toxins are designed primarily to disrupt the cellular membrane. Many type II exotoxins have hemolysin activity, which causes red blood cells to lyse in vitro.

- Type III toxins: Intracellular toxins. Intracellular toxins must be able to gain access to the cytoplasm of the target cell to exert their effects. Some bacteria deliver toxins directly from their cytoplasm to the cytoplasm of the target cell through a needle-like structure. The effector proteins injected by the type III secretion apparatus of Yersinia into target cells are one example. Another well-known group of intracellular toxins is the AB toxins. The 'B'-subunit attaches to target regions on cell membranes, allowing the the 'A'-subunit to enter through the membrane and stimulate enzymatic actions that affects internal cellular bio-mechanisms. The structure of these toxins allows for the development of specific vaccines and treatments. For example, certain compounds can be attached to the B unit, which the body learns to recognize, and which elicits an immune response. This allows the body to detect the harmful toxin if it is encountered later, and to eliminate it before it can cause harm to the host. Toxins of this type include cholera toxin, pertussis toxin, Shiga toxin, and heat-labile enterotoxin from E. coli.

- Toxins that damage the extracellular matrix. These toxins allow the further spread of bacteria and consequently deeper tissue infections. Examples are hyaluronidase and collagenase.

Exotoxins are susceptible to antibodies produced by the immune system, but many exotoxins are so toxic that they may be fatal to the host before the immune system has a chance to mount defenses against it.

Endotoxin examples

The prototypical examples of endotoxin are lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or lipo-oligo-saccharide (LOS) found in the outer membrane of various gram-negative bacteria. The term LPS is often used interchangeably with endotoxin, owing to its historical discovery. In the 1800s, it became understood that bacteria could secrete toxins into their environment, which became broadly known as "exotoxin." The term endotoxin came from the discovery that portions of gram-negative bacteria themselves can cause toxicity, hence the name endotoxin. Studies of endotoxin over the next 50 years revealed that the effects of "endotoxin" was in fact due to lipopolysaccharide.

LPS consist of a polysaccharide (sugar) chain and a lipid moiety, known as lipid A, which is responsible for the toxic effects. The polysaccharide chain is highly variable among different bacteria. Humans are able to produce antibodies to endotoxins after exposure but these are generally directed at the polysaccharide chain and do not protect against a wide variety of endotoxins.

There are, however, endotoxins other than LPS. For example, delta endotoxin of Bacillus thuringiensis makes crystal-like inclusion bodies next to the endospore inside the bacteria. It is toxic to larvae of insects feeding on plants, but is harmless to humans (as we do not possess the enzymes and receptors necessary for its processing followed by toxicity).

The only known gram positive bacteria that produces endotoxin is Listeria monocytogenes.

Dinoflagellates

Dinoflagellates can produce toxic substances of danger to humans. For instance, one should avoid consuming mussels along the west coast of the United States during the warmer months. This is because dinoflagellates create elevated levels of toxins in the water that do not harm the mussels, but if consumed by humans can bring on illness. Usually the United States government monitors the levels of toxins throughout the year at fishing sites.

Fungi

Two species of mold—Aspergillus flavus and Aspergillus parasiticus—produce aflatoxin, which can contaminate potatoes afflicted by the mold (Lerner and Lerner 2004). This can lead to serious and even fatal illness.

Plants

Many plants produce toxins designed to protect against insects and other animal consumers, or fungi.

The roots of the tobacco plant produce a substance called nicotine, which is stored mainly in the leaves. Nicotine is a powerful poison and seems to benefit the plant by protecting it from insects, working by attacking the junctions between the insects' nerve cells (Stuart 2004). Tobacco leaves are sometimes soaked or boiled and the water sprayed on other plants as an organic insecticide. Nicotine is also a deadly poison to humans. Two to four drops (pure nicotine is an oily liquid) are a fatal dose for an adult. Smoking and chewing tobacco results in a much smaller dose; however, people have died as a result of mistaking wild tobacco for an edible herb and boiling and eating a large quantity (IPCS 2006).

Poison ivy, poison hemlock, and nightshade are other plants that produce toxins that work against humans.

Ricin is found in the castor bean plant, and is the third most deadly toxin to humans known, after the toxins produced by Clostridium botulinum and Clostridium tetani (Lerner and Lerner 2004). There is no known vaccine or antidote, and if exposed symptoms can appear within hours (nausea, muscle spasms, severe lung damage, and convulsion) and death from pulmonary failure within three days (Lerner and Lerner 2004).

Animals

Many animals use toxins for predation or defense. Well known examples include pit vipers, such as rattlesnakes, that possess hemotoxins that target and destroy red blood cells and are transmitted through the bloodstream; the brown recluse or "fiddle back" spider that uses necrotoxins that cause death in the cells they encounter and destroy all types of tissues; and the black widow spider, most scorpions, the box jellyfish, elapid snakes, and the cone snail that use neurotoxins that primarily affect the nervous system of animals.

The puffer fish produces the deadly toxin tetrodotoxin in its liver and ovaries; it blocks nerve conduction (Blakemore and Jennett 2001).

Terminology: Toxin, poison, venom

The term toxin comes from the Greek τοξικόν toxikon, meaning "(poison) for use on arrows." In the context of biology, poisons are substances that can cause damage, illness, or death to organisms, usually by chemical reaction or other activity on the molecular scale, when a sufficient quantity is absorbed by an organism.

Toxin is a subcategory of poison, referring to a substance produced by a living organism. However, when used non-technically, the term "toxin" is often applied to any poisonous substance. Many non-technical and lifestyle journalists also follow this usage to refer to toxic substances in general, though some specialist journalists maintain the distinction that toxins are only those produced by living organisms. In the context of alternative medicine the term toxin often is used nonspecifically as well to refer to any substance claimed to cause ill health, ranging anywhere from trace amounts of pesticides to common food items like refined sugar or additives like artificial sweeteners and MSG.

In pop psychology, the term toxin sometimes is used to describe things that have an adverse effect on psychological health, such as a "toxic relationship," "toxic work environment," or "toxic shame."

Venoms usually are defined as biologic toxins that are delivered subcutaneously, such as injected by a bite or sting, to cause their effect. In normal usage, a poisonous organism is one that is harmful to consume, but a venomous organism uses poison to defend itself while still alive. A single organism can be both venomous and poisonous.

The derivative forms "toxic" and "poisonous" are synonymous.

A weakened version of a toxin is called a toxoid (Lerner and Lerner 2004). Toxids have been treated chemically or by heat to limit their toxicity while still allowing them to stimulate the formation of antibodies.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blakemore, C., and S. Jennett. 2001. The Oxford Companion to the Body. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 019852403X

- International Programme on Chemical Safety (IPCS). 2006. Nicotiana tabacum. International Programme on Chemical Safety. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

- Lerner, K. L., and B. W. Lerner. 2004. Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence, and Security. Detroit, MI: Thomson/Gale. ISBN 0787675466

- Ryan, K. J., and C. G. Ray, eds. 2004. Sherris Medical Microbiology, 4th ed. McGraw Hill. ISBN 0838585299

- Sofer, G., and L. Hagel. 1997. Handbook of Process Chromatography: A Guide to Optimization, Scale-up, and Validation. Academic Press. ISBN 012654266X

- Stuart, D. 2004 Dangerous Garden. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. ISBN 067401104

- Todar, K. 2002. Mechanisms of Bacterial Pathogenicity: Endotoxins. Todar's Online Textbook of Bacteriology. Retrieved August 24, 2007.

External links

All links retrieved May 1, 2023.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Caregory:Life sciences