Difference between revisions of "Tariff" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

Import tariffs are no longer an important source of revenues in developed countries. In the United States, for example, revenues from import duties in 1808 amounted to twice the total of government expenditures, while in 1837 they were less than one-third of such expenditures. Until near the end of the nineteenth century the customs receipts of the U.S. government made up about half of all its receipts. This share had fallen to about 6 percent of all receipts before the outbreak of [[World War II]] and it has since further decreased. | Import tariffs are no longer an important source of revenues in developed countries. In the United States, for example, revenues from import duties in 1808 amounted to twice the total of government expenditures, while in 1837 they were less than one-third of such expenditures. Until near the end of the nineteenth century the customs receipts of the U.S. government made up about half of all its receipts. This share had fallen to about 6 percent of all receipts before the outbreak of [[World War II]] and it has since further decreased. | ||

| − | + | ==Arguments in favor of import tariffs== | |

There are many arguments in favor of the use of import tariffs to protect home [[industry|industries]] that have been forwarded by advocates of [[Protectionism]]: | There are many arguments in favor of the use of import tariffs to protect home [[industry|industries]] that have been forwarded by advocates of [[Protectionism]]: | ||

Revision as of 22:24, 18 July 2008

| Public finance |

|

| This article is part of the series: Finance and Taxation |

| Taxation |

|---|

| Ad valorem tax · Consumption tax Corporate tax · Excise Gift tax · Income tax Inheritance tax · Land value tax Luxury tax · Poll tax Property tax · Sales tax Tariff · Value added tax |

| Tax incidence |

| Flat tax · Progressive tax Regressive tax · Tax haven Tax rate |

| Economic policy |

| Monetary policy Central bank · Money supply |

| Fiscal policy Spending · Deficit · Debt |

| Trade policy Tariff · Trade agreement |

| Finance |

| Financial market Financial market participants Corporate · Personal Public · Banking · Regulation |

A tariff or customs duty is a tax levied upon goods as they cross national boundaries, usually by the government of the importing country. The words tariff, duty, and customs are generally used interchangeably. Since the goods cannot be landed until the tax is paid, it is the easiest tax to collect, and the cost of collection is small. Traders seeking to evade tariffs are known as smugglers.

Introduction to tariffs

Tariffs, or customs duties, may be levied on imported goods by a government either:

- to raise revenue or

- to protect domestic industries.

However, a tariff designed primarily to raise revenue may exercise a strong protective influence and a tariff levied primarily for protection may yield revenue. Therefore Gottfried Haberler in his Theory of International Trade (Haberler 1936) suggested that the best objective distinction between revenue duties and protective duties (disregarding the motives of the legislators) is to be found in their discriminatory effects as between domestic and foreign producers.

If domestically produced goods bear the same taxation as similar imported goods, or if the goods subject to duty are not produced at home, even after the duty has been levied, and if there can be no home-produced substitutes toward which demand is diverted because of the tariff, the duty is not protective.

A purely protective tariff tends to shift production away from the export industries into the protected domestic industries and those industries producing substitutes for which demand is increased.

On the other hand, a purely revenue tariff will not cause resources to be invested in industries producing the taxed goods or close substitutes for such goods, but it will divert resources from the production of export goods to the production of those goods and services upon which the additional government receipts are spent.

From the purely revenue standpoint, a country can levy an equivalent tax on domestic production, to avoid protecting it, or select a relatively small number of imported articles of general consumption and subject them to low duties so that there will be no tendency to shift resources into industries producing such taxed goods (or substitutes for them).

For instance, during the period when it was on a free-trade basis, Great Britain followed the latter practice, levying low duties on a few commodities of general consumption such as tea, sugar, tobacco, and coffee. Unintentional protection was not a major issue, because Britain could not have produced these goods domestically.

If, on the other hand, a country wishes to protect its home industries, its list of protected commodities will be long and the tariff rates high.

Classification

Tariffs may be classified into three groups: transit duties, export duties, and import duties.

Transit duties

This type of duty is levied on commodities that originate in one country, cross another, and are consigned to a third. As the name implies, transit duties are levied by the country through which the goods pass. The most direct and immediate effect of transit duties is to reduce the amount of commodities traded internationally and raise their cost to the importing country.

Such duties are no longer important instruments of commercial policy, but, during the mercantilist period (seventeenth and eighteenth centuries) and even up to the middle of the nineteenth century in some countries, they played a role in directing trade and controlling certain trade routes. The development of the German Zollverein (customs union) in the first half of the nineteenth century was partly the result of Prussia's exercise of power to levy transit duties. In 1921 the Barcelona Statute on Freedom of Transit abolished all transit duties.

Export duties

The main function of export duties was to safeguard domestic supplies rather than to raise revenue. Export duties were first introduced in England by a statute of 1275 that imposed them on hides and wool. By the middle of the seventeenth century the list of commodities subject to export duties had increased to include more than 200 articles. They were significant elements of mercantilist trade policies.

With the growth of free trade in the nineteenth century, export duties became less appealing; they were abolished in England in 1842, in France in 1857, and in Prussia in 1865. At the beginning of the twentieth century only a few countries levied export duties: for example, Spain still levied them on coke and textile waste; Bolivia and Malaya on tin; Italy on objects of art; and Romania on hides and forest products.

The neo-mercantilist revival in the 1920s and 1930s brought about a limited reappearance of export duties. In the United States, export duties were prohibited by the Constitution, mainly because of pressure from the South, which wanted no restriction on its freedom to export agricultural products.

Export duties are now generally levied by raw-material-producing countries rather than by advanced industrial countries. Differential exchange rates are sometimes used to extract revenues from export sectors. Commonly taxed exports include coffee, rubber, palm oil, and various mineral products. The state-controlled pricing policies of international cartels such as the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) have some of the characteristics of export duties.

Export duties may act as a form of protection to domestic industries. As examples, Norwegian and Swedish duties on exports of forest products were levied chiefly to encourage milling, woodworking, and paper manufacturing at home. Similarly, duties on the export from India of untanned hides after World War I were levied to stimulate the Indian tanning industry. In a number of cases, however, duties levied on exports from colonies were designed to protect the industries of the mother country and not those of the colony.

If the country imposing the export duty supplies only a small share of the world's exports and if competitive conditions prevail, the burden of an export duty will likely be borne by the domestic producer, who will receive the world price minus the duty and other charges. But if the country produces a significant fraction of the world output and if domestic supply is sensitive to lower net prices, then output will fall and world prices may rise and as a consequence not only domestic producers but also foreign consumers will bear the export tax. How far a country can employ export duties to exploit its monopoly position in supplying certain raw materials depends upon the success other countries have in discovering substitutes or new sources of supply.

Export duties are no longer used to a great extent, except to tax certain mineral and agricultural products. Several resource-rich countries depend upon export duties for much of their revenue.

Import duties

Import duties are the most important and most common types of custom duties. As noted above, they may be levied either for revenue or protection or both. An import tariff may be either:

- specific,

- ad valorem, or

- compound (a combination of both).

A "specific tariff" is a levy of a given amount of money per unit of the import, such as $1.00 per yard or per pound.

An "ad valorem tariff," on the other hand, is calculated as a percentage of the value of the import. Ad valorem rates furnish a constant degree of protection at all levels of price (if prices change at the same rate at home and abroad), while the real burden of specific rates varies inversely with changes in the prices of the imports.

A specific tariff, however, penalizes more severely the lower grades of an imported commodity. This difficulty can be partly avoided by an elaborate and detailed classification of imports on the basis of the stage of finishing, but such a procedure makes for extremely long and complicated tariff schedules. Specific tariffs are easier to administer than ad valorem rates, for the latter often raise difficult administrative issues with respect to the valuation of imported articles.

Import tariffs are not a satisfactory means of raising revenue because they encourage uneconomic domestic production of the dutied item. Even if imports constitute the bulk of the available revenue base, it is better to tax all consumption, rather than only consumption of imports, in order to avoid uneconomical protection.

Import tariffs are no longer an important source of revenues in developed countries. In the United States, for example, revenues from import duties in 1808 amounted to twice the total of government expenditures, while in 1837 they were less than one-third of such expenditures. Until near the end of the nineteenth century the customs receipts of the U.S. government made up about half of all its receipts. This share had fallen to about 6 percent of all receipts before the outbreak of World War II and it has since further decreased.

Arguments in favor of import tariffs

There are many arguments in favor of the use of import tariffs to protect home industries that have been forwarded by advocates of Protectionism:

- Cheap labor

Less developed countries have a natural cost advantage as labor costs in those economies are low. They can produce goods less expensively than developed economies and their goods are more competitive in international markets.

- Infant industries

Protectionists argue that infant, or new, industries must be protected to give them time to grow and become strong enough to compete internationally, especially industries that may provide a firm foundation for future growth, such as computers and telecommunications. However, critics point out that some of these infant industries never "grow up."

- National security concerns

Any industry crucial to national security, such as producers of military hardware, should be protected. That way the nation will not have to depend on outside suppliers during political or military crises.

- Diversification of the economy

If a country channels all its resources into a few industries, no matter how internationally competitive those industries are, it runs the risk of becoming too dependent on them. Keeping weaker industries competitive through protection may help in diversifying the nation’s economy.

Analysis and discussion of Import Tariffs Effect on a Domestic Economy

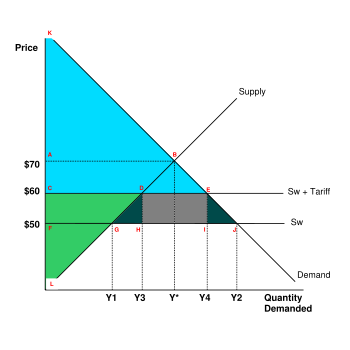

To make the above text a bit more palatable we shall produce a simple graph—of an Import Tariffs levied on a specific good in a specific country—from which we shall try to derive the economic effect on the domestic economy of that country.

In the following graph we see the effect that an import tariff has on the domestic economy. Three cases will be discussed:

Closed economy

In a closed economy without trade we would see equilibrium at the intersection of the demand and supply curves (point B), yielding prices of $70 and an output of Y*.

In this case the consumer surplus would be equal to the area inside points A, B and K, while producer surplus is given as the area A, B and L.

Free international trade

When incorporating free international trade into the model we introduce a new supply curve denoted as SW.

Under the somewhat simplistic, yet for the example permissible, assumptions --- i. e. perfect elasticity of supply of the good and boundless quantity of world production --- we assume the international price of the good is $50 ( i. e. $20 less than the domestic equilibrium price).

As a result of this price differential we see that domestic consumers will import these cheaper international alternatives, while decreasing consumption of domestic made produce. This reduction in domestic production is equal to Y* minus Y1, thus reducing producer surplus from the area A, B and L to F, G and L. This shows that domestic producers are clearly worse off with the introduction of international trade.

On the other hand, we see that consumers are now paying a lower price for the goods, which increases the consumer surplus from the area A, B and K to a new surplus of F, J and K. From this increase in consumer surplus we see that some of this surplus was, in fact, redistributed from producer surplus, equal to the area A, B, F and G.

However, the net societal gains from trade, in terms of net surplus, are equal to the area B, G and J. The level of consumption has increased from Y* to Y2, while imports are now equal to Y2 minus Y1.

Introduction of a tariff

Let’s now introduce a tariff of $10/unit on imports. This has the effect of shifting the world supply curve vertically by $10 to SW + Tariff. Again, this will create a redistribution of surplus within the model.

We see that consumer surplus will decrease to the area C, E and K, which is a net loss of the area C, E, F and J. This now makes consumers unambiguously worse off than under a free trade regime, but still better off than under a system without trade. Producer surplus has increased, as they are now receiving an extra $10 per sale, to the area C, D and L. This is a net gain of the area C, D, F and G. With this increase in price the level of domestic production has increased from Y1 to Y3, while the level of imports has reduced to Y4 minus Y3.

The government also receives an increase in revenues as a result of the tariff equal to the area D, E, H and I. In dollar terms this figure is essentially $10*(Y4-Y3). However, with this redistribution of surplus we do see that some of the redistributed consumer surplus is lost. This loss of surplus is known as a deadweight loss, and is essentially the loss to society from the introduction of the tariff. This area is equal to the area E, I and J. The area D, G and H is a transfer from consumers to those the producers must pay to bring their product to market.

Without tariffs, only those producers/consumers able to produce the product at the world price will have the money to purchase it at that price. The small FGL triangle will be matched by an equally small mirror image triangle of consumers still able to buy. With tariffs, a larger CDL triangle and its mirror will survive.

What conclusion to make from the graph?

First of all, the graph concerns a generic country and analyzes the closed, the free-trade and the tariff-on-import economy. It does so vis-à-vis the consumers first; although the producers and a state revenue (when tariff is applied) is discussed briefly too. In other words, only somewhat simplified economic impacts are analyzed.

The problem of “free-trade vs. import tariff protection,” particularly in developing countries, has become mostly socio-political issue and instead of improved well-being of the developing country’s population at stake is, instead, much more important goal of the government is to assure the political stability of the country, which can only be kept together when there is a maximum employed people.

But the only way to achieve full (or maximum) employment is to protect local low productivity but employment-heavy sectors, such as: agriculture, forestry, textile & clothing industry and, perhaps some other nation-specific sectors, from the cheap import.

The rationale should be: Unemployed people cannot buy even cheapest products yet poverty is a sure way to political upheavals as it follows from this excerpt:

A doubling of the prices of major cereals on international markets since mid-2007 has sharply increased the risk of hunger and poverty in developing countries where many people spend the bulk of their household income on food. Already food riots and protests have been seen across Asia and Africa, and Haiti's government has fallen. International aid agencies are struggling to feed people in their care. (Lynn and Ryan 2008)

In the next part of the article we shall discuss some of the historical developments in so far the “tariff vs. free trade” question goes. However, one clear conclusion can be made already at this time. There is almost nothing (coming from NGOs, such as: GATT, WTO etc.) that would analyze the socio-political impact of these trade agreements; it is always about economics only.

Brief history of tariffs and trade agreement in the world

Any contractual arrangement between states concerning their trade relationships is referred to as a Trade Agreement or a Free Trade Agreement. Trade agreements may be bilateral or multilateral, that is, between two states or more than two states. For most countries international trade is regulated by unilateral barriers of several types, including tariffs, non-tariff barriers, and outright prohibitions. Trade agreements are one way to reduce these barriers, thereby opening all parties to the benefits of increased trade.

In most modern economies the possible coalitions of interested groups are extremely numerous. Additionally, the variety of possible unilateral barriers is great. Further, there are other, non-economic reasons for some observed trade barriers, such as national security and stability or the desire to preserve or insulate local culture from foreign influences. Thus, it is not surprising that successful trade agreements are very complicated. Some common features of trade agreements are: (1) reciprocity, (2) a most-favored-nation clause, and (3) national treatment of non-tariff barriers.

Reciprocity

Reciprocity is a necessary feature of any agreement. If each required party does not gain by the agreement as a whole, it has no incentive to agree to it. If agreement takes place, it may be assumed that each party to the agreement expects to gain at least as much as it loses. Thus, for example, Country A, in exchange for reducing barriers to Country B's products, thereby benefiting A's consumers and B's producers, will insist that Country B reduce barriers to Country A's products, benefiting Country A's producers and perhaps B's consumers.

Most-favored-nation clause

The most-favored-nation (MFN) clause protects against the possibility that one of the parties to the current agreement will subsequently selectively lower barriers further to another country. For example, Country A might agree to reduce tariffs on some goods from Country B in exchange for reciprocal concessions and then further reduce tariffs for the same goods from Country C in exchange for other concessions. But if A's consumers can get the goods in question more cheaply from C because of the tariff difference, B gets nothing for its concessions. Most-favored-nation status means that A is required to extend the lowest existing tariff on specified goods to all its trading partners having such status. Thus, if A agrees to a lower tariff later with C, B automatically gets the same lower tariff.

The advantages granted under the MFN clause may be conditional or unconditional.

- Unconditional clause operates automatically whenever appropriate circumstances arise. The country drawing benefit from it is not called on to make any fresh concession. By contrast, the partner invoking a conditional MFN clause must make concessions equivalent to those extended by the third country.

In practice, therefore, a country negotiating a trade agreement must measure the advantages it is willing to concede in terms of the benefits these concessions will provide collaterally to that third country which is the most competitive. In other words, the concessions that may be granted are determined by the minimum protection that the negotiating state deems indispensable to protect its home producers. This sets a major limitation on the scope of bilateral negotiations, and this is also why the proponents of free trade consider that the unconditional MFN clause is the only practical way by which to obtain the progressive reduction of customs duties. Those who favor protectionism are resolutely against it, preferring the conditional form of the clause or some equivalent mechanism.

- The conditional form of the clause may at first sight seem more equitable. But it has the major drawback of being liable to raise a dispute each time it is invoked, for it is by no means easy for a country to evaluate the compensation it is being offered as in fact being equivalent to the concession made by the third country.

The conditional MFN clause was generally in use in Europe until 1860, when the so-called Cobden-Chevalier Treaty between Great Britain and France established the unconditional form as the pattern for most European treaties The United States used the conditional MFN clause from its first trade agreement, signed with France in 1778, until the passage of the Tariff Act of 1922, which terminated the practice. (The Trade Reform Bill of 1974, however, in effect restored to the U.S. president the authority to designate preferential tariff treatment, subject to approval by Congress.)

National treatment of non-tariff restrictions (NTBs)

A “national treatment of non-tariff restrictions” clause is necessary because most of the properties of tariffs can be easily duplicated with an appropriately designed set of non-tariff restrictions (or barriers-NTBs.) These can include discriminatory regulations, selective excise or sales taxes, special “health” requirements, quotas, “voluntary” restraints on importing, special licensing requirements, etc., not to mention outright prohibitions. Instead of trying to list and disallow all of the possible types of non-tariff restrictions, signatories to an agreement insist on similar treatment to that given to domestically produced goods of the same type.

Even without the constraints imposed by most-favored-nation and national treatment clauses, sometimes general multilateral agreements are easier to reach than separate bilateral agreements. In many cases the possible loss from a concession to one country is almost as great as that which would result from a similar concession to all or many countries. The gains to efficient producers from worldwide tariff reductions are large enough to warrant substantial concessions. The most successful and important multilateral trade agreement in modern times is the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT). It includes provisions for reciprocity, most-favored-nation status, and national treatment of non-tariff restrictions. Since GATT took effect in 1948, world tariff levels have dropped substantially and world trade has rapidly expanded.

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT)

GATT (General Agreement on Tariff and Trade) was concluded by 23 countries at Geneva, in 1947 (to take effect on Jan. 1, 1948), it was considered an interim arrangement pending the formation of a United Nations agency to supersede it. When such an agency failed to emerge, GATT was amplified and further enlarged at several succeeding negotiations. It subsequently proved to be the most effective instrument of world trade liberalization, playing a major role in the massive expansion of world trade in the second half of the 20th century. By the time GATT was replaced by the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, 125 nations were signatories to its agreements, which had become a code of conduct governing 90 percent of world trade.

GATT's most important principle was that of trade without discrimination, in which each member nation opened its markets equally to every other. As embodied in unconditional most-favored nation clauses, this meant that once a country and its largest trading partners had agreed to reduce a tariff, that tariff cut was automatically extended to every other GATT member. GATT included a long schedule of specific tariff concessions for each contracting nation, representing tariff rates that each country had agreed to extend to others.

Another fundamental principle was that of protection through tariffs rather than through import quotas or other quantitative trade restrictions; GATT systematically sought to eliminate the latter. Other general rules included uniform customs regulations and the obligation of each contracting nation to negotiate for tariff cuts upon the request of another. An escape clause allowed contracting countries to alter agreements if their domestic producers suffered excessive losses as a result of trade concessions.

GATT's normal business involved negotiations on specific trade problems affecting particular commodities or trading nations, but major multilateral trade conferences were held periodically to work out tariff reductions and other issues. Seven such “rounds” were held from 1947 to 1993, starting with those held at Geneva in 1947 (concurrent with the signing of the general agreement); at Annecy, France, in 1949; at Torquay, England, in 1951; and at Geneva in 1956 and again in 1960–1962. The most important rounds were the so-called Kennedy Round (1964–67), the Tokyo Round (1973–79), and the Uruguay Round (1986–1994), all held at Geneva. These agreements succeeded in reducing average tariffs on the world's industrial goods from 40 percent of their market value in 1947 to less than 5 percent in 1993.

The Uruguay Round negotiated the most ambitious set of trade-liberalization agreements in GATT's history. The worldwide trade treaty adopted at the round's end slashed tariffs on industrial goods by an average of 40 percent, reduced agricultural subsidies, and included groundbreaking new agreements on trade in services. The treaty also created a new and stronger global organization, the WTO, to monitor and regulate international trade. GATT went out of existence with the formal conclusion of the Uruguay Round on April 15, 1994. Its principles and the many trade agreements reached under its auspices were adopted by the WTO.

Thus, the WTO began the Doha Round in Doha, Qatar in November 2001 with the objective to lower trade barriers around the world, permitting free trade between countries of varying prosperity. However, talks stalled over a divide between the developed nations led by the European Union, the United States and Japan and the major developing countries (represented by the G20 developing nations), led and represented mainly by India, Brazil, China, and South Africa.

WTO and developing world

However, the whole question of “how to protect sectors that employ most indigenous people from cheaper import” also constitutes the perpetual dilemma to the policy makers in developing countries. It was also inherited by WTO to find a reasonable solution, since the original lessening of people’s well-being by increasing the import tariffs ( or NTBs ), as discussed in FIG. 1 above, should be compared with: (a) massive unemployment and political consequences arising from it and, (b) missing on the introduction of major exporting sector.

The, relatively minuscule to modest, increase of the state revenues do not play any important role at all in the socio-economic and, above all, political stability optimization which should be the real goal of every country’s government.

Thus, the problem is to recognize really “untouchable domestic sectors that should be protected from cheap import” because: they employ the majority of indigenous people or, based on abundance of local raw materials and much lower wages of workers and professionals, they could become with know-how transfer from developing countries’ NGOs serious internationally exporting sectors very soon.

Particularly agriculture has been of critical importance to many developing countries in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) and employment, and thus plays a key role in meeting development objectives such as poverty alleviation, food security and, hence, political stbility . Negotiations on agriculture began already in 2000 under the “built-in agenda” of the Uruguay Round, with the long-term objective of establishing a fair and market-oriented trading system through a programme of fundamental reform encompassing strengthened rules and specific commitments on support and protection in order to correct and prevent restrictions and distortions in world agricultural markets.

The WTO eventually recognized the problem there and introduced the so called “special and differential treatment.” This consists of delineating the permitted level of domestic support to agriculture in any specific developing country into “boxes” of different colors:

- Green box: supports considered not to distort trade and, therefore, permitted with no limits.

- Blue box: permitted supports linked to production, but subject to production limits, and therefore minimally trade-distorting.

- Amber box: supports considered to distort trade and therefore subject to reduction commitments, in other words, prohibited.

But, generally speaking, and despite all of these near-catastrophic political consequences of doing away with tariffs and NTBs in developing countries that appeared in the first decade of twenty-first century (Lynn and Ryan 2008), NAFTA and WTO still advocate an optimistic, whatever long-time, vision of the future. Prosperity is to be based on intellectuals skills and managerial know-how more than on routine hand labor.

Consequently, the negotiations are aimed at substantial improvements in market access; reductions of, with a view to phasing out, all forms of export subsidies; and substantial reductions in trade-distorting domestic support. There are to be only eventual concessions in terms of “some special and differential treatment for developing countries” as seen in the above “boxes.”

In the meantime, much more serious tariff problems and oppositions to free international trade have been experienced in the developing and/or transitional countries with infant industries, without tariff protection, may not survive the competition with cheap import. Such countries also have a very cheap labor force—apart from unemployment and outright poverty—producing low-priced products that these countries try to “dump” onto the international market, and, obviously, cannot because of WTO’s standards and the above ”trade-distorting domestic support axiom.”

And yet, despite of all the WTO "call-to-arms" over tariffs, there is perfectly legal tool in the international trade that, particularly, in trade between the US and EU (and many non-European developing countries) plays a role the tariffs could never aspired to. This tool is called Value Added Tax (VAT).

Tariffs vs. VAT (or sales tax) effectiveness on countries’ well-being

Developed countries

It should first be noted that the same imports subject to a VAT may also be subject to separate tariffs or custom duties. But even with the complete elimination of tariffs among EU countries, the VAT would still be collected on all imports to achieve tax neutrality and ensure a level tax playing field for both foreign and domestic firms. The problems start when VAT countries trade with non-VAT countries.

The main feature of VAT is the “export rebate” that returns to the exporter the VAT ( equivalent tax ) percentage of the product sold abroad.

As global trade negotiations over the past half-century have lowered tariffs on imports, global trade rules have not regulated the rate of VAT taxes that countries may apply to imports. In the 1960s, the Governments of Europe imposed a 10.4 percent average tariff on imports and only three EU nations imposed a VAT, with an average standard rate of 13.4 percent. Today, the EU nations impose an average tariff of 4.4 percent, plus an average 19.4 percent VAT equivalent tax, i.e. a total levy of 23.8 percent on U.S. goods and service imports. The protection is the same, whatever its name.

EXAMPLE: When the German car, valued in Germany at $ 23,600, is imported to the U.S., Germany rebates the 16 percent VAT to the manufacturer, allowing the export value of the car to be $19,827.59. Moreover, when the German car is imported to the U.S. no U.S. tax comparable to the VAT is assessed, so the car is allowed to enter the U.S. market at a price under $20,000. Hence, apart from the tax rebate in the country of production the car is much more price competitive with the cars of similar class manufactured in the U.S..

Solution taken into global economy

Such a differential provides a powerful incentive for U.S. ( and no-VAT) -headquartered companies to shift production and jobs to nations that use a VAT. With such a shift, they get both a tax rebate on their exports into the American market and avoid double taxation (U.S. direct tax, plus national VAT) on sales in that foreign market. They pay only the VAT on local sales. Thousands of U.S. -headquartered companies are now producing and exporting goods and services from nations that use a VAT and getting the VAT tax advantage in global trade.

Developing countries

The limited administrative capacity in many developing countries suggests, however, that the implementation of the crediting arrangements of VAT is often imperfect (at least for firms other than the largest firms, which may be subject to special arrangements). Clearly there is a risk that these taxes become de facto tariffs even for formal sector firms.

A distinctive feature of a VAT is, essentially, a tax on the purchase of informal operators ( who in developing countries form 40% - 60% of GDP ) from formal sector business and, not least, on their imports. The potential importance of the creditable withholding taxes, levied by many developing countries leaves a clear conclusion: The tariffs, even in cases of informal sector of a small economy, may not need to be employed. To preserve government revenue and increase welfare, in the face of efficiency improved tariff cuts, the conditions are established under which a VAT alone is fully optimal, precisely because it is in part a tax on informal sector production.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Laird, Sam. Back to Basics: Market Access Issues in the Doha agenda. United Nations Publications, 2003. ISBN 978-9211125764

- Doran, Charles F. and Gregory P. Marchildon. The NAFTA Puzzle: Political Parties and Trade in North America (1994)

- Eckes, Alfred. Opening America's Market: U.S. Foreign Trade Policy since 1776 (1995)

- Haberler, Gottfried Von. The Theory of International Trade. London: William Hodge and Company, 1936 (German ed. 1933).

- Kaplan, Edward S. Prelude to Trade Wars: American Tariff Policy, 1890-1922 Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1994. ISBN 031329061X

- Kaplan, Edward S. American Trade Policy: 1923-1995. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996. ISBN 0313294801

- Bereman, Wayne. Free Markets Deserve Protection; By Definition! The American Protectionist Society. Retrieved July 10, 2008.

- Taussig, F. W. Tariff Encyclopedia Britannica (11th edition, 1911) vol 26 pp. 422-27. Retrieved July 10, 2008.

- Lynn, Jonathan and Missy Ryan. ANALYSIS-WTO deal seen having little impact on food prices Reuters, April 18, 2008. Retrieved July 14, 2008.

External links

- Market Access Map: Making import tariffs and market access barriers transparent

- Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) Tariff Database

- Interactive Tariff and Trade Dataweb United States International Trade Commission

- Tariffs and Import Fees

- International trade Encyclopædia Britannica.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Tariff history

- Import_tariff history

- Infant_industry_argument history

- Tariff_in_American_history history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.