Orpheus

Orpheus (Greek: Ορφεύς; pronunciation: ohr'-fee-uhs)[1] is a figure from Greek mythology called by Pindar "the father of songs". His name does not occur in Homer or Hesiod, but he was known by the time of Ibycus (c.530 B.C.E.).

Orpheus was believed to be one of the chief poets and musicians of antiquity, and the inventor or perfector of the lyre. With his music and singing, he could charm wild beasts, coax the trees and rocks into dance and even divert the course of rivers. As one of the pioneers of civilization, he is said to have taught humanity the arts of medicine, writing and agriculture. Closely connected with religious life, Orpheus was an augur and seer; practised magical arts, especially astrology; founded or rendered accessible many important cults, such as those of Apollo and the Thracian god Dionysus; instituted mystic rites both public and private; and prescribed initiatory and purificatory rituals. In addition, Pindar describes Orpheus as the harpist and companion of Jason and the Argonauts.[2]

Etymology

Several etymologies for the name Orpheus have been proposed. A probable suggestion is that it is derived from a hypothetical PIE verb *orbhao-, "to be deprived", from PIE *orbh-, "to put asunder, separate". Cognates would include Greek orphe, "darkness", and Greek orphanos, "fatherless, orphan", from which comes English "orphan" by way of Latin. Orpheus would therefore be semantically close to goao, "to lament, sing wildly, cast a spell", uniting his seemingly disparate roles as disappointed lover, transgressive musician and mystery-priest into a single lexical whole. The word "orphic" is defined as mystic, fascinating and entrancing, and, probably, because of the oracle of Orpheus, "orphic" can also signify "oracular".

Mythology

Early life

Orpheus' father was a Thracian king; his mother was the muse Calliope. While living with his mother and his eight beautiful aunts on Parnassus, he met the god Apollo who was courting the laughing muse Thalia. Apollo became fond of Orpheus and gave him a little golden lyre, and taught him to play it. Orpheus's mother taught him to make verses for singing.

Argonautic expedition

Orpheus joined the expedition of the Argonauts. The centaur Chiron had warned the Argonaut leader Jason that only with the aid of Orpheus would they be able to navigate past the Sirens unscathed. The Sirens lived on three small, rocky islands called Sirenum scopuli and played irresistibly beautiful songs that enticed sailors and their ships to the islands' craggy shoals, where the ships would be wrecked and the sailors killed by the sirens. However, when Orpheus heard the sirens, he drew his lyre and played music more beautiful than theirs, drowning out their alluring but deadly song.

Death of Eurydice

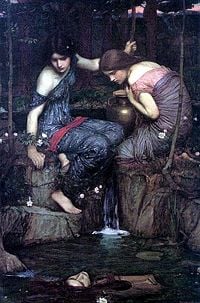

The most famous story in which Orpheus figures is that of his wife Eurydice (also known as Agriope). While fleeing from Aristaeus (son of Apollo), Eurydice ran into a nest of snakes which bit her fatally on her legs. Distraught, Orpheus played such sad songs and sang so mournfully that all the nymphs and gods wept. On their advice, Orpheus travelled to the underworld and by his music softened the hearts of Hades and Persephone (he was the only person ever to do so), who agreed to allow Eurydice to return with him to earth on one condition: he should walk in front of her and not look back until he had reached the upper world. In his anxiety he broke his promise, and Eurydice vanished again from his sight.

The story in this form belongs to the time of Virgil, who first introduces the name of Aristaeus. Other ancient writers, however, speak of Orpheus' visit to the underworld; according to Plato, the infernal gods only "presented an apparition" of Eurydice to him. Ovid says that Eurydice's death was not caused by fleeing from Aristaeus but by dancing with naiads on her wedding day.

The story of Eurydice may actually be a late addition to the Orpheus myths. In particular, the name Eurudike ("she whose justice extends widely") recalls cult-titles attached to Persephone. The myth may have been mistakenly derived from another Orpheus legend in which he travels to Tartarus and charms the goddess Hecate.

The descent to the Underworld of Orpheus is paralleled in other versions of a worldwide theme: the Japanese myth of Izanagi and Izanami, the Akkadian/Sumerian myth of Inanna's Descent to the Underworld, and Mayan myth of Ix Chel and Itzamna. The mytheme of not looking back is reflected in the story of Lot's wife when escaping from Sodom. More directly, the story of Orpheus is similar to the ancient Greek tales of Persephone captured by Hades and similar stories of Adonis captive in the underworld. However, the developed form of the Orpheus myth was entwined with the Orphic mystery cults and, later in Rome, with the development of Mithraism and the cult of Sol Invictus; the predecessors of Orpheus.

Death

According to some versions of the story (notably Ovid's), Orpheus forswore the love of women after the death of Eurydice and took only youths as his lovers; he was reputed to be the one who introduced pederasty to the Thracians, teaching them to "love the young in the flower of their youth".

According to a Late Antique summary of Aeschylus's lost play Bassarids, Orpheus at the end of his life disdained the worship of all gods save the sun, whom he called Apollo. One early morning he went to the Oracle of Dionysus (there are ongoing discussions whether this is Perperikon or Mount Pangaion) to salute his god at dawn, but was torn to death by Thracian Maenads for not honoring his previous patron, Dionysus. Here his death is analogous with the death of Dionysus, to whom therefore he functioned as both priest and avatar. Ovid (Metamorphoses XI) also recounts that the Thracian Maenads, Dionysus' followers, angry for having been spurned by Orpheus in favor of "tender boys," first threw sticks and stones at him as he played, but his music was so beautiful even the rocks and branches refused to hit him. Enraged, the Maenads tore him to pieces during the frenzy of their Bacchic orgies. Later, the story would sometimes be seen from a Christian moralist angle: in Albrecht Dürer's drawing (illustration, left) the ribbon high in the tree is lettered Orfeus der erst puseran ("Orpheus, the first sodomite").

His head and lyre, still singing mournful songs, floated down the swift Hebrus to the Mediterranean shore. There, the winds and waves carried them on to the Lesbos shore, where the inhabitants buried his head and a shrine was built in his honour near Antissa; there his oracle prophesied, until it was silenced by Apollo (Life of Apollonius of Tyana, book v.14). The lyre was carried to heaven by the Muses, and was placed among the stars. The Muses also gathered up the fragments of his body and buried them at Leibethra below Mount Olympus, where the nightingales sang over his grave. His soul returned to the underworld, where he was re-united at last with his beloved Eurydice.

Bulgarian archeologists have discovered, near Tatul, an ancient Thracian tomb that some have described as "the tomb of Orpheus".[3]

Orphic poems and rites

A number of Greek religious poems in hexameter were attributed to Orpheus, as they were to similar miracle-working figures, like Bakis, Musaeus, Abaris, Aristeas, Epimenides, and the Sybil. Of this vast literature, only two examples survive whole: a set of hymns composed at some point in the second or third century AD, and an Orphic Argonautica composed somewhere between the fourth and sixth centuries AD. Earlier Orphic literature, which may date back as far as the sixth century B.C.E., survives only in papyrus fragments or in quotations.

In addition to serving as a storehouse of mythological data along the lines of Hesiod's Theogony, Orphic poetry was recited in mystery-rites and purification rituals. Plato in particular tells of a class of vagrant beggar-priests who would go about offering purifications to the rich, a clatter of books by Orpheus and Musaeus in tow (Republic 364c-d). Those who were especially devoted to these ritual and poems often practiced vegetarianism, abstention from sex, and refrained from eating eggs and beans — which came to be known as the Orphikos bios, or "Orphic way of life".[4]

The Derveni papyrus, found in Derveni, Macedonia, in 1962, contains a philosophical treatise that is an allegorical commentary on an Orphic poem in hexameters, a theogony concerning the birth of the gods, produced in the circle of the philosopher Anaxagoras, written in the second half of the fifth century B.C.E. Fragments of the poem are quoted making it "the most important new piece of evidence about Greek philosophy and religion to come to light since the Renaissance"[5]. The papyrus dates to around 340 B.C.E., during the reign of Philip II of Macedon, making it Europe's oldest surviving manuscript.

The historian William Mitford wrote in 1784 that the very earliest form of a higher and cohesive ancient Greek religion was manifest in the Orphic poems.[6]

W.K.C. Guthrie wrote that Orpheus was the founder of mystery religions and the first to reveal to men the meanings of the initiation rites.[7]

Mystery schools

Besides the better known "mystery schools" of Pythagoras and Plato, there were well established "Orphic" mystery schools that purported to convey esoteric and metaphysical knowledge. Due to societal persecution and suppression, these were secret schools for the study of the mysteries of the "Inner Nature" of man and of surrounding nature. By understanding these mysteries, the student attempted to perceive his intimate relationship with Divinity, and strove through self-discipline and devotion to become at one with his "Inner God". [8]

Post-classical Orpheus

The Orpheus legend has remained a popular subject for writers, artists, musicians and filmmakers.

Poetry

- In the late thirteenth or early fourteenth century, the tale of Orpheus was mixed with Celtic fairy lore in the Middle English metrical romance Sir Orfeo. In this version, Sir Orfeo rescues his wife Heurodis from the King of Fairy, whose realm contains both the dead, and people thought to be dead but merely taken by the fairies. This story lasted long enough to be collected in the Child ballads as King Orfeo (albeit in fragmentary form).

- In the Divine Comedy Dante sees the shade of Orpheus along with those of numerous other "virtuous pagans" in Limbo.

- The play Henry VIII by William Shakespeare and John Fletcher includes a song sung by a lady about Orpheus. It is not certain which author wrote the song.[1]

- The Czech-German poet Rainer Maria Rilke, sometimes called the last of the romantic authors, wrote the Sonnets to Orpheus immediately following the Duino Elegies.

- The English poet John Milton repeatedly made allusions to the figure of Orpheus in his work, most centrally in "Lycidas" (1637).

- The Polish poet Czeslaw Milosz wrote Orpheus and Euridice as an elegy to his late wife Carol in 2003.

- W. H. Auden wrote a poem called "Orpheus" about the conflicting desires "to be bewildered and happy or most of all the knowledge of life".

- Orpheus appears as a member of Odysseus's last voyage from Ithaca in Nikos Kazantzakis' epic poem The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel.

Classical music

The story of Orpheus and Eurydice has been the subject of operas, cantatas, ballets, and other works through the history of western classical music:

- Angelo Poliziano's Orfeo, a musical Renaissance considered by some scholars an important forerunner of the opera genre.

- Jacopo Peri's opera Euridice (1600)

- Giulio Caccini's opera Euridice (written 1600 / first performance 1602)

- Claudio Monteverdi's opera Orfeo (1607)

- Stefano Landi's opera La morte d'Orfeo (1619)

- Luigi Rossi's opera Orfeo (1647)

- Marc-Antoine Charpentier's unfinished opera La descente d'Orphée aux enfers (date unknown: mid-1680s?)

- Louis-Nicolas Clerambault's cantata "Orphee" (1710)

- Georg Philipp Telemann's opera "Orpheus" (1726)

- Johann Caspar Ferdinand Fischer's Musikalischer Parnassus (c. 1738) comprises nine dance suites dedicated to the Muses; it is thought the final dance of the Uranie suite tells the story of Orpheus & Eurydice.

- Christoph Willibald Gluck's opera Orfeo ed Euridice (1762)

- Johann Gottlieb Naumann's opera Orfeo ed Euridice (1785)

- Joseph Haydn's opera L'anima del filosofo, ossia Orfeo ed Euridice (composed 1791)

- Friedrich August Kanne's Orpheus (1807)

- In a 1985 article in 19th Century Music musicologist Owen Jander controversially argued that the 2nd movement (Andante con moto) of Beethoven's 4th Piano Concerto was programmatically modelled after the Orpheus myth.

- Jacques Offenbach's operetta Orpheus in the Underworld (1858)

- Darius Milhaud's opera Les malheurs d'Orphée (1924)

- Ernst Krenek's opera Orpheus und Eurydike (1926)

- Stravinsky's ballet "Orpheus" (1948).

- Orphee 53, Opera in Musique Concrete style by Pierre Henry and Pierre Schaeffer (1953)

- Mark Alburger's "Orpheus Cycle" (1982), six art songs to lipogrammatic texts of Matthew Kiell

- Harrison Birtwistle's opera The Mask of Orpheus (1986)

- Philip Glass's opera Orphée (1993).

- Leslie Burrs and John A. Williams, Vanqui (2000), a retelling of the Orpheus legend set during the time of the Underground Railroad.

Other music

- Former Genesis guitarist Steve Hackett composed in 2005 an opera for guitar and orchestra named Metamorpheus on the classical Orpheus myth.

- A modernised version of the myth of Orpheus is told in Nick Cave's song The Lyre Of Orpheus from the double album Abattoir Blues/The Lyre of Orpheus.

- Orpheus is a song on David Sylvian's album Secrets of the Beehive; complementarily, a later remaster of the album has the song Promise (The Cult of Eurydice).

- Orpheus in Red Velvet is a song on Marc Almond's album Enchanted.

- Orpheus is mentioned in the Wallflowers song "nearly beloved."

- Orpheus is also mentioned in the Cruxshadows song "Cassandra"

- Eurydice, a lament for the woman of the title, is a song by Sleepthief on their album The Dawnseeker.

Drama

- The Tennessee Williams play Orpheus Descending is a modern retelling of the Orpheus myth set in 1950s America.

- Sarah Ruhl's play Eurydice is an interpretive retelling of the myth of Orpheus from the point of view of his wife, Eurydice.

- Jean Anouilh's Eurydice (1941) sets the story among a troupe of performers in 1930s France.

Film

- Orphée, directed by Jean Cocteau (1949)

- Black Orpheus (Orfeu Negro), directed by Marcel Camus (1959), from the play Orfeu da Conceição by Brazilian poet Vinicius de Moraes; retells the story during the Rio de Janeiro carnival

- Orfeu, directed by Carlos Diegues (1999), essentially a remake of Black Orpheus.

Novels

- The myth of Orpheus was retold in The Sandman comic books by Neil Gaiman, where he is recast as the son of the titular character.

- It is retold in the Hugo and Nebula-winning novella, Goat Song by Poul Anderson.

- Russell Hoban's "The Medusa Frequency" alludes heavily to the Orpheus myth. In fact, the head of Orpheus is a central character, albeit inside another character's mind.

- Thomas Pynchon's novel "Gravity's Rainbow" uses the Orpheus myth as one structure, with Slothrop as Orpheus and postwar Germany as Hades. There are many references to the afterlife in Slothrop's "descent" into the continent, the yacht the Anubis being one example.

- Salman Rushdie used the Orpheus and Eurydice narrative as a mythic underpinning to the magical realist novel The Ground Beneath Her Feet (see also the song of the same name recorded by U2 with lyrics provided by Rushdie).

XTC's Andy Partridge and Slapp Happy's Peter Blegvad spend 13 years, on and off, creating the album Orpheus: The Lowdown, a dense mix of music, poetry and spoken word.

Sonya Taaffe's "Shade and Shadow" presents the Orpheus myth in relation to the modern fear of death and isolation.

George Selden, in The Cricket in Times Square, has a character describe the cricket as an Orpheus, and then, just before the cricket leaves, has the music from its concert cause all of Times Square to fall still, and then escape from the square to cause blocks of New York city to fall still, listening.

In the TV series Angel, Orpheus is the name given to a drug taken by humans to give them a rush when their blood is drunk by a vampire. Faith uses it in the series to take down Angelus.

There is a role-playing game developed by White Wolf Game Studios titled Orpheus. In it players take on the role of projectors, individuals who can project their souls into the lands of the dead.

The 2001 film Moulin Rouge! is reminiscent in its plot of the tale of Orpheus and Eurydice. The character Christian (played by Ewan McGregor) has the gift of song and follows the Bohemian/Dionysian ideals. A loose allegorical connection can be made between most characters and events in the two tales. The film appears to be almost equally inspired by Orpheus & Eurydice and by La Boheme, a cunning act of synthesis by writer/director Baz Luhrmann. On the other hand, see The Lady of the Camellias.

In the anime Saint Seiya Hades, there is a legendary silver saint named Lyra Orpheè, whose special weapon is a lyre and his background is similar to that of his mythical counterpart.

The name of the New York-based Orpheus Chamber Orchestra was inspired by the mythical figure.

The name Orpheus is used in the cartoon television series The Venture Bros.. Doctor Byron Orpheus is a necromancer who lives in a converted wing of Dr. Venture's lab. In a somewhat ironic scene, Dr. Orpheus visits his master and teacher, who has taken the form of Cerberus. The intended nature of this scene is unknown, and the meeting of the two in that manner may be entirely coincidental.

Orpheus's theatrical qualities are memorialized in the name of the numerous "Orpheum" theaters in cities across the United States, once part of a chain of vaudeville and motion picture theaters [see Orpheum Circuit, Inc.].

The band .: Orphic Observance :. from San Francisco, California is an improvisation-based musical group founded in 2002 by Bro. Jack Elder, a New Orleans transplant the San Francisco Bay Area. Maintaining an open membership of local musicians, the group is dedicated to the god Orpheus as the archetypical musician, seeking to promote musicianship as a self-defined spiritual/religious discipline.

Orpheus is a song by the band Ash on their album Meltdown.

Darkwave band The Crüxshadows refer to the Orphic myth in the song "Eurydice (Don't follow me)".

Canadian electronic musicians Orphx allude to various aspects of the Orpheus mythos in their work.

Orpheus is mentioned in a monologue by title character Fefu in Maria Irene Fornes' "Fefu and Her Friends".

On his debut album "The Dawnseeker" musician Sleepthief wrote the song "Eurydice" about Orpheus' attempt at saving his wife from Hades.

Maurice Blanchot used the The Gaze of Orpheus as a metaphor for the artistic process. The Gaze of Orpheus is also the namesake of one of his articles.

The radio drama production "Day of the Dead" (2006) by Frederick Greenhalgh is a creative retelling of the myth of Orpheus, set in modern day New Orleans. In the story, a young man heads to the city looking for his missing girlfriend and encounters characters similar to those in the myth and elsewhere in mythology.

There is a reference in the anime series Angel Sanctuary where the main character Setsuna Mundo decided to bring back his murdered young sister/lover Sara from the underworld just like Orpheus.

Orpheus in astronomy

In planetary science, Orpheus refers to a proto-planet that collided with Earth early in the solar system's history. This collision led to the birth of Earth's moon that formed after the violent impact because the Earth’s gravity pulled the remnants of Orpheus into its orbit.

This planetary collision is believed to be of vital importance in the development of life on Earth. Prior to the impact, Earth was almost completely covered with oceans so only the highest peaks rose above sea level. In addition, the atmosphere of Earth was very dense and had low levels of oxygen. As a result of Earth’s collision with Orpheus, much of the ocean water was ejected into space as were a large percentage of the atmospheric gases. These changes made it possible for life on Earth to evolve as we currently know it.

Spoken-word myths - audio files

| Orpheus myths as told by story tellers |

|---|

| 1. Orpheus and the Thracians, read by Timothy Carter, music by Steve Gorn, compiled by Andrew Calimach |

| Bibliography of reconstruction: Pindar, Pythian Odes, 4.176 (462 B.C.E.); Roman marble bas-relief, copy of a Greek original from the late 5th c. (c. 420 B.C.E.); Aristophanes, The Frogs 1032 (c. 400 B.C.E.); Phanocles, Erotes e Kaloi, 15 (3rd c. BC); Apollonios Rhodios, Argonautika, i.2 (c. 250 B.C.E.); Apollodorus, Library and Epitome 1.3.2 (140 B.C.E.); Diodorus Siculus, Histories I.23, I.96, III.65, IV.25 (1st c. BC); Conon, Narrations, 45 (50 - 1 B.C.E.); Virgil, Georgics, IV.456 (37 - 30 B.C.E.); Horace, Odes, I.12; Ars Poetica 391-407 (23 B.C.E.); Ovid, Metamorphoses X.1-85, XI.1-65 (AD 8); Seneca, Hercules Furens 569 (1st c. AD); Hyginus, Poetica Astronomica II.7 Lyre (2st c. AD); Pausanias, Description of Greece, 2.30.2, 9.30.4, 10.7.2 (AD 143 - 176); Anonymous, The Clementine Homilies, Homily V Chapter XV.-Unnatural Lusts (c. AD 400); Anonymous, Orphic Argonautica (5th c. AD); Stobaeus, Anthologium (c. AD 450); Second Vatican Mythographer, 44. Orpheus |

Notes

- ↑ The mythological name "Orpheus" is commonly pronounced "ohr'-fee-uhs" in English, although some names have a different pronunciation in ancient Greek; see "Encyclopedia Mythica: Pronunciation guide" webpage:Pantheon-pron.

- ↑ Grote, p. 21.

- ↑ http://www.ancient-bulgaria.com/2006/08/31/tatul-the-possible-tomb-of-orpheus/

- ↑ Moore, p. 56 says that "the use of eggs and beans was forbidden, for these articles were associated with the worship of the dead".

- ↑ Richard Janko, Bryn Mawr Classical Review, (2006) of K. Tsantsanoglou, G.M. Parássoglou, T. Kouremenos (editors), 2006. The Derveni Papyrus (Florence: Olschki) series "Studi e testi per il "Corpus dei papiri filosofici greci e latini", vol. 13]).

- ↑ Mitford, p.89: "But the very early inhabitants of Greece had a religion far less degenerated from original purity. To this curious and interesting fact, abundant testimonies remain. They occur in those poems, of uncertain origin and uncertain date, but unquestionably of great antiquity, which are called the poems of Orpheus or rather the Orphic poems [particularly in the Hymn to Jupiter, quoted by Aristotle in the seventh chapter of his Treatise on the World: Ζευς πρωτος γενετο, Ζευς υςατος, x. τ. ε]; and they are found scattered among the writings of the philosophers and historians."

- ↑ Guthrie, p.17. "As founder of mystery-religions, Orpheus was first to reveal to men the meaning of the rites of initiation (teletai). We read of this in both Plato and Aristophanes (Aristophanes, Frogs, 1032; Plato, Republic, 364e, a passage which suggests that literary authority was made to take the responsibility for the rites". Guthrie goes on to write about "... charms and incantations of Orpheus which we may also read of as early as the fifth century B.C.E. Our authority is Euripides, Alcestis (referencing the Charm of the Thracian Tablets) and in Cyclops, the spell of Orpheus".

- ↑ Knoche, Grace F. Mystery Schools Through the Ages.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ovid, Metamorphoses X, 1-105; XI, 1-66; Apollodorus, Bibliotheke I, iii, 2; ix, 16 & 25; Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica I, 23- 34; IV, 891-909.

- Albertus Bernabé (ed.), Orphicorum et Orphicis similium testimonia et fragmenta. Poetae Epici Graeci. Pars II. Fasc. 1. Bibliotheca Teubneriana, München/Leipzig: K.G. Saur, 2004. ISBN 3-598-71707-5. review of this book

- George Grote, A History of Greece, 1846.

- William Keith Chambers Guthrie, Orpheus and Greek Religion: a Study of the Orphic Movement, 1935.

- William Mitford, The History of Greece, 1784. Cf. v.1, Chapter II, Religion of the Early Greeks.

- Clifford H. Moore, Religious Thought of the Greeks, 1916.

- Erwin Rohde, Psyche, 1925. cf. Chapter 10, The Orphics.

- William Smith, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 1870, article on Orpheus, [2]

- The Mystical Hymns of Orpheus (tr. Thomas Taylor), 1896. [3]

- Martin Litchfield West, The Orphic Poems, 1983. There is a sub-thesis in this work that early Greek religion was heavily influenced by Central Asian shamanistic practices. One major point of contact was the ancient Crimean city of Olbia.

- Margaret Fuller Ossoli, Orpheus, a sonnet about his trip to the underworld.

External links

- Greek Mythology Link, Orpheus.

- Online Text: The Orphic Hymns translated by Thomas Taylor

- The Story of Orpheus.

- Orphica in English and Greek, Select Resources

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.