Difference between revisions of "Nomad" - New World Encyclopedia

Kendra Kline (talk | contribs) m (I deleted two parts that were beyond help and are soon going to be rewritten.) |

Kendra Kline (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

[[Image:Prokudin-Gorskii-18.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Kazakh nomads in the steppes of the Russian Empire, ca. 1910]] | [[Image:Prokudin-Gorskii-18.jpg|thumb|right|250px|Kazakh nomads in the steppes of the Russian Empire, ca. 1910]] | ||

[[Image:Nomads near Namtso.jpg|thumb|250px|Pastoral nomads camping near Namtso, [[Tibet]] in 2005]] | [[Image:Nomads near Namtso.jpg|thumb|250px|Pastoral nomads camping near Namtso, [[Tibet]] in 2005]] | ||

| − | + | Nomadic societies are those that do not remain sedentary for signficant lengths of time. There is some overlap between the term "nomadic" and the term "pastoralists". Most often, these words are used as though they are interchangable. Pastoralism is also referred to as animal husbandry and is actually a subsistence method. Some nomads practice pastoralism. | |

| − | + | ||

| + | The anthropological research on nomadic communities is somewhat sparse and the older the information is, the less reliable. Anthropology used to group societies based on notions of "complexity" and progress. For this reason, nomadic communities were often seen as intellectually simple. We must realize, however, that many nomadic societies, despite what we may see as a lack of "technology" have very complex social structures. | ||

| + | |||

== Nomadic lifestyle == | == Nomadic lifestyle == | ||

| + | |||

| + | In pastoralism, herds are followed as they move, to ensure food for the group. Also, the constant moving around helps to keep the land from being overused. The second kind of nomadism, called peripatetic nomadism, involves those who move from place to place, offering a specific trade. These types of nomadic groups are common in industrialized nations. | ||

== Attributes of nomads == | == Attributes of nomads == | ||

| Line 14: | Line 18: | ||

==History of nomadic peoples== | ==History of nomadic peoples== | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Eurasian Avars=== | ===Eurasian Avars=== | ||

| Line 71: | Line 72: | ||

Several known groups in the United States include the Northern and Southern Travellers (each of which have their own subcategories) and the Western Travellers. The Traveller language (Shelta) is dying out and only the older Travellers still know the language completely. | Several known groups in the United States include the Northern and Southern Travellers (each of which have their own subcategories) and the Western Travellers. The Traveller language (Shelta) is dying out and only the older Travellers still know the language completely. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| Line 100: | Line 85: | ||

{{Main|Pygmy}} | {{Main|Pygmy}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | In an anthropological context, a Pygmy is specifically a member of one of the hunter-gatherer people living in equatorial rainforests characterised by their short height (below 1.5 metres, or 4.5 feet, on average). Pygmies are found throughout central Africa, with smaller numbers in south-east Asia (see Negrito). Members of so-called Pygmy groups often consider the term derogatory, instead preferring to be called by the name of their ethnic group (e.g., Baka, Mbuti). | ||

===Ababdeh=== | ===Ababdeh=== | ||

| Line 126: | Line 113: | ||

[[image:Innus.png|thumb|right|260px|Innu communities of Québec and Labrador]] | [[image:Innus.png|thumb|right|260px|Innu communities of Québec and Labrador]] | ||

| − | The '''Innu''' are the [[indigenous people|indigenous]] inhabitants of an area they refer to as [[Nitassinan]], which comprises most of what Canadians refer to as eastern [[Québec]] and [[Newfoundland and Labrador|Labrador]], [[Canada]]. Their population in 2003 includes about 18,000 persons, of which 15,000 live in Québec. They are known to have lived on these lands as [[hunter-gatherers]] for several thousand years, living in tents made of animal skins. Their subsistance activities were historically centered on hunting and trapping [[caribou]], [[moose]], [[deer]] and small game. Their language, [[Montagnais]] or Innu-aimun, is spoken throughout Nitassinan, with certain dialect differences. Innu-aimun is related to the language spoken by the Cree of the James Bay region of Québec and [[Ontario]]. | + | The '''Innu''' (which means 'human being' in Montagnais) are the [[indigenous people|indigenous]] inhabitants of an area they refer to as [[Nitassinan]], which comprises most of what Canadians refer to as eastern [[Québec]] and [[Newfoundland and Labrador|Labrador]], [[Canada]]. Their population in 2003 includes about 18,000 persons, of which 15,000 live in Québec. They are known to have lived on these lands as [[hunter-gatherers]] for several thousand years, living in tents made of animal skins. Their subsistance activities were historically centered on hunting and trapping [[caribou]], [[moose]], [[deer]] and small game. Their language, [[Montagnais]] or Innu-aimun, is spoken throughout Nitassinan, with certain dialect differences. Innu-aimun is related to the language spoken by the Cree of the James Bay region of Québec and [[Ontario]]. |

The Innu people are frequently sub-divided into two groups, the ''Montagnais'' who live along the north shore of the [[Gulf of Saint Lawrence]], in Québec, and the less numerous ''Naskapi'' ["inland people" in Innu-aimun] who live farther north. The Innu themselves recognize several distinctions (e.g. Mushuau Innut, Maskuanu Innut, Uashau Innut) based on different regional affiliations and various dialects of the Innu language. | The Innu people are frequently sub-divided into two groups, the ''Montagnais'' who live along the north shore of the [[Gulf of Saint Lawrence]], in Québec, and the less numerous ''Naskapi'' ["inland people" in Innu-aimun] who live farther north. The Innu themselves recognize several distinctions (e.g. Mushuau Innut, Maskuanu Innut, Uashau Innut) based on different regional affiliations and various dialects of the Innu language. | ||

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 18:58, 3 August 2006

Nomadic societies are those that do not remain sedentary for signficant lengths of time. There is some overlap between the term "nomadic" and the term "pastoralists". Most often, these words are used as though they are interchangable. Pastoralism is also referred to as animal husbandry and is actually a subsistence method. Some nomads practice pastoralism.

The anthropological research on nomadic communities is somewhat sparse and the older the information is, the less reliable. Anthropology used to group societies based on notions of "complexity" and progress. For this reason, nomadic communities were often seen as intellectually simple. We must realize, however, that many nomadic societies, despite what we may see as a lack of "technology" have very complex social structures.

Nomadic lifestyle

In pastoralism, herds are followed as they move, to ensure food for the group. Also, the constant moving around helps to keep the land from being overused. The second kind of nomadism, called peripatetic nomadism, involves those who move from place to place, offering a specific trade. These types of nomadic groups are common in industrialized nations.

Attributes of nomads

History of nomadic peoples

Eurasian Avars

The Eurasian Avars were a nomadic people of Eurasia, supposedly of proto-Mongolian Turkic stock, who migrated from eastern Asia into central and eastern Europe in the 6th century. The Avar rule persisted over much of the Pannonian plain up to the early 9th century. Avars were driven westward when the Gokturks defeated the Hephthalites in the 550s and the 560s. They entered Europe in the sixth century and, having been bought off by the Eastern Emperor Justinian I, pushed north into Germany (as Attila the Hun had done a century before).

Finding the country unsuited to their nomadic lifestyle (and the Franks stern opponents), they turned their attention to the Pannonian plain, which was then being contested by two Germanic tribes, the Lombards and the Gepids. Siding with the Lombards, they destroyed the Gepids in 567 and established a state in the Danube River area. Their harassment soon (ca. 568) forced the Lombards into northern Italy, a migration that marked the last Germanic migration in the Migrations Period. By the early 9th century, internal discord and the external pressure started to undermine the Avar state. The Avars were finally liquidated during the 810s by the Franks under Charlemagne and the First Bulgarian Empire under Krum.

Hephthalites

The Hephthalites, also known as "White Huns," were an Indo-European and quite possibly an Eastern Iranian nomadic people who lived across western China, Central Asia, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northwest India in the fourth through sixth centuries AD. They had no cities or system of writing, lived in felt tents, and practiced polyandry.

The term Hephthalite derives from Greek, supposedly a rendering of Hayathelite (from the term Haital = "Big/Powerful" in the dialect of Bukhara), the name used by Persian writers to refer to a 6th century empire on the northern and eastern periphery of their land. As a group they appear to be distinct from the Huns who ravaged Europe in the fourth century AD.

Wu Hu

Wu Hu (Chinese: 五胡; pinyin: Wǔ Hú; literally "Five Hu") is a collective term for various non-Chinese steppe tribes during the period from the Han Dynasty to the Northern Dynasties. These nomadic tribes originally resided outside China proper, but gradually migrated into Chinese areas during the years of turmoil between the Eastern Han Dynasty and Three Kingdoms. These non-Chinese tribes, whom the Han had fought to a standstill, seized the opportunity afforded by the weakness of the central government to extend their settlement of pastoral lands into the fertile North China Plain.

The Rebellion of the Eight Kings during the Western Jin Dynasty triggered a large scale Wu Hu uprising from 304, which resulted in the sacking of the Chinese capitals at Luoyang (311) and Chang'an. The Xiongnu Kingdom of Han-Former Zhao captured and executed the last two Jin emperors as the Western Jin Dynasty collapsed in 317. Many Chinese fled to the south of Yangtze River as numerous tribesmen of the Wu Hu and remnants of the Jin wreaked havoc in the north. Fu Jiān temporarily unified the north but his brilliant achievement was destroyed after the Battle of Feishui. The Northern Wei Dynasty unified northern China again in 439 and ushered in the period of the Northern Dynasties.

The term Wu Hu was first used in Cui Hong's Shiliuguochunqiu, which recorded the history of the five tribes' ravaging Northern China from the early 4th century to the mid 5th century. Wu Hu means "five nomadic groups", hence the alternative "Five Hu." The most accepted composition of Wu Hu included five nomadic tribes: Xiōngnú (匈奴, sometimes identified with the Huns), Xiānbēi (鮮卑), Dī (氐), Qiāng (羌), and Jié (羯) although different groups of historians and historiographers have their own definitions.

After later historians determined that more than five nomadic tribes took part, Wu Hu has become a collective term for all non-Chinese nomads residing in North China at the time. The time at which the ravages occurred is called The Period of Wu Hu (五胡時代) or the Wu Hu Chaos in China (五胡亂華, literally "Five Hú Wreak-havoc-on China"). States founded by Wu Hu were called the Sixteen Kingdoms.

Nomadic people in industrialized nations

Roma and Sinti

Kalderash

The Kalderash are one of the largest groups within the Roma people. They were traditionally smiths and metal workers. Their name means "cauldron buider". Many gypsies living in Romania, have the surname "Caldararu" which means they or their ancestors belonged to this clan or "satra" as it is known in their language. They typically were bronze and gold workers. As their traditional crafts become less profitable, they are trying to find new ways of coping, and are facing difficulties assimilating, as education is not a priority within the culture.

Gitanos

The Gitanos (IPA /xitanos/ or /hitanos/) are a Roma people that live in Spain, Portugal, and southern France. Gitanos is a Spanish name, in southern France they are known as Gitans or more generally Tziganes (includes the other French Roma) and in Portugal they are known as Ciganos. Similarly to the English word gypsy, the name Gitano comes from Egiptiano (Egyptian), because in past centuries it was thought their origins were in the country of Egypt. Today, however, it is generally thought that their origin lies in the Punjab region of India.

After losing their original Romany language, they used Caló, a jargon with Spanish grammar and Romany vocabulary. "Caló" means "dark" in Caló and the Caló word for "Gitano" is calé, also "the dark ones". Caló is one of the influences of later Germanía and modern Spanish slang and criminal jargon.

Vocally, The Gitano characterize the flamenco by giving precendence of emotion over text, with emotional outbursts and extended vowels. This is typical of Gypsy song in general.

Gitanos are said to never use a whip on a horse, mule, or donkey. As a result, they have a reputation as excellent horse-trainers.

Pavee

Irish Travellers are a nomadic or itinerant people of Irish origin living in Ireland, Great Britain and the United States. They refer to themselves as The Pavee. An estimated 25,000 Travellers live in Ireland, 15,000 in Great Britain and 10,000 in the United States.

Irish Travellers are distinguished from the settled communities of the countries in which they live by their own language and customs. Shelta is the traditional language of Travellers but they also speak English with a distinct accent and mannerisms. The historical origins of Travellers as a group has been a subject of dispute. Some argue that the Irish Travellers are descended from another nomadic people called the Tarish. It was once widely believed that Travellers were descended from landowners who were made homeless in Oliver Cromwell's military campaign in Ireland, but evidence shows that they have dwelt in Ireland since at least the Middle Ages.

Several known groups in the United States include the Northern and Southern Travellers (each of which have their own subcategories) and the Western Travellers. The Traveller language (Shelta) is dying out and only the older Travellers still know the language completely.

Indigenous nomadic peoples

Examples of indigenous nomadic peoples are Pygmies of Southern Africa, Ababdeh of Egypt, Bahktiari of Iran, The Bedouin desert-dwellers, Innu of Quebec and Labrador, Kuchis (Kochai) of Afghanistan, Tuaregs of West Africa, Nenets of Russia, Moken of Thailand and Myanmar, the Sami of Northern Scandinavia and Russia, and the Bushmen of Southern Africa. Many Native Americans and Indigenous Australians were nomadic prior to Western contact, although they were not a pastoral people in that they did not systematically raise animals on whose products they depended.

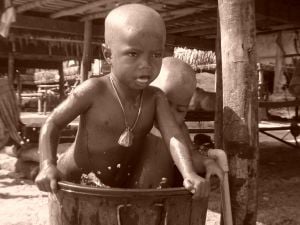

Pygmies

In an anthropological context, a Pygmy is specifically a member of one of the hunter-gatherer people living in equatorial rainforests characterised by their short height (below 1.5 metres, or 4.5 feet, on average). Pygmies are found throughout central Africa, with smaller numbers in south-east Asia (see Negrito). Members of so-called Pygmy groups often consider the term derogatory, instead preferring to be called by the name of their ethnic group (e.g., Baka, Mbuti).

Ababdeh

The Ababdeh are nomads living in the area between the Nile and the Red Sea, in the vicinity of Aswan in Egypt. This name refers to several such African tribes.

Some of them penetrated into Upper Egypt, where they earned a subsistence by the transportation of merchandise on their camels. They traded chiefly in senna, and in charcoal made of the acacia wood. Burckhardt regarded them as Arabs; Carl Ritter conjectured that they are descended from the people known, under the Roman emperors, as Blemmeyes; but Rüppell was of the opinion that they are a branch of the Ethiopean ethnic group established at Meroë. In their manner and customs (as of 1851), they were similar to the Bedouins.

Bakhtiari

The Bakhtiari (or Bakhtiyari) are a group of southwestern Iranian people.

A small percentage of Bakhtiari are still nomadic pastoralists, migrating between summer quarters (yaylāq, ييلاق) and winter quarters (qishlāq, قشلاق). Bakhtiaris speak Luri. Numerical estimates of their total population widely vary. In Khuzestan, Bakhtiari tribes are primarily concentrated in the eastern part of the province.

Bakhtiaris primarily inhabit the provinces of Lorestan, Khuzestan, Chahar Mahaal and Bakhtiari, and Isfahan. In Iranian mythology, the Bakhtiari consider themselves to be descendants of Fereydun, a legendary hero from the Persian national epic, Shahnameh.

Many significant Iranian politicians and dignitaries are of Bakhtiari origin.

The Bedouin

Innu

The Innu (which means 'human being' in Montagnais) are the indigenous inhabitants of an area they refer to as Nitassinan, which comprises most of what Canadians refer to as eastern Québec and Labrador, Canada. Their population in 2003 includes about 18,000 persons, of which 15,000 live in Québec. They are known to have lived on these lands as hunter-gatherers for several thousand years, living in tents made of animal skins. Their subsistance activities were historically centered on hunting and trapping caribou, moose, deer and small game. Their language, Montagnais or Innu-aimun, is spoken throughout Nitassinan, with certain dialect differences. Innu-aimun is related to the language spoken by the Cree of the James Bay region of Québec and Ontario.

The Innu people are frequently sub-divided into two groups, the Montagnais who live along the north shore of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence, in Québec, and the less numerous Naskapi ["inland people" in Innu-aimun] who live farther north. The Innu themselves recognize several distinctions (e.g. Mushuau Innut, Maskuanu Innut, Uashau Innut) based on different regional affiliations and various dialects of the Innu language.

Kuchis (Kochai)

Kuchis are a tribe of Pashtun nomads in Afghanistan. They represent an estimated six million of Afghanistan's 25 million people. The group is singled out by the United Nations Assistance Mission in Afghanistan as one of the largest vulnerable populations in the country.

Tuaregs

Nenets

Moken

The Moken (sometimes called "Sea Gypsies", Thai: มอแกน; also called Salone or Salong) are an ethnic group with about 2,000 to 3,000 members who maintain a nomadic, sea-based culture. Their Malayo-Polynesian language is originally from Malaya and likely immigrated to the Myanmar and Thailand areas from China 4,000 years ago. The group is unrelated to the Gypsy culture of Eurasia.

Their knowledge of the sea enables them to live off its organisms by using simple tools such as nets and spears to forage for food. What is not consumed is dried atop their boats, then used for trade at local markets for other necessities. During the monsoon season, they build additional boats while occupying temporary huts.

The Burmese and Thai governments have made attempts at assimilating the people into their own culture, but these efforts have failed. The Thai Moken have permanently settled in villages located on two islands: Phuket and Phi Phi. Many of the Burmese Moken are still nomadic people who roam the sea most of their lives in small hand-crafted wooden boats called Kabang, which serve not just as transporation, but also as kitchen, bedroom, living area. Unfortunately much of their traditional life, built on the premise of life as outsiders, is under threat and appears to be diminishing.

Those islands received much media attention in 2005 during the Southeast Asia Tsunami, where hundreds of thousands of lives were lost in the disaster.

The Moken's knowledge of the sea managed to spare all but one of their lives - one of an elderly, handicapped man. However, their settlements and about one-fifth of their boats were destroyed.

Mrazig

The Mrazig are a previously nomadic people who live in and around the town of Douz, Tunisia. Numbering around 50,000 they are the descendants of the Banu Saleim tribe who left the Arabian peninsula in the eighth century. They lived in Egypt, then Libya and finallty arrived in Tunisia in the thirteenth century.

Sami

Bushmen

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Further reading

- Sadr, Karim. The Development of Nomadism in Ancient Northeast Africa, University of Pennsylvania Press, 1991. ISBN 0812230663

- Cowan, Gregory. Nomadology in Architecture: Ephemerality, Movement and Collaboration University of Adelaide 2002 (available: [1])

- Grousset, René. L'Empire des Steppes (1939)

- Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Félix, A Thousand Plateaus (1980)

External links

- Moken: Sea Gypsies @ National Geographic (Subscription Required)

- Moken: Sea Gypsies @ National Geographic (Tsunami Extra)

- Phuket Magazine: The Moken - Traditional Sea Gypsies

- ProjectMaje.org - Burma "Sea Gypsies" Compendium

- Mergui Archipelago Project

- Ethnologue report for Moken

- Official website of the Innu Nation of Labrador.

- Official website of the Naskapi Nation of Kawawachikamach, Québec

- "Portail Innu", Québec

- Website of the Tshikapisk Foundation (a non profit Innu organization focussing on social and cultural renewal)

- Virtual Museum of Canada - Tipatshimuna: Innu stories from the land

- Canada's Tibet: The Killing of the Innu, a report from Survival International (PDF file) (A study of Innu communities of Labrador)

- Distinctions between "Naskapi", "Montagnais" and "Innu"

- Montagnais Indians (Quebec) - Article in the Catholic Encyclopedia

- CBC Digital Archives - Davis Inlet: Innu community in crisis

- Irish Travellers' Movement.

- Pavee Point Travellers Centre

- Traveller Visibility Group or TVG

- Bibliography of Irish Travellers sources—University of Liverpool

- Irish Medical Journal article Traveller Health: A National Strategy 2002-2005

- Francie Barrett boxing profile

- Official site for movie - Pavee Lackeen: The Traveller Girl

- The Travellers: Ireland’s Ethnic Minority

- Interview with local expert on Dale Farm

- Travellers' Rest: Fact And Fiction About Irish Travellers in the U.S.A.

- Nan: The Life of an Irish Travelling Woman, by Sharon Gmelch, 1991.

- The Irish Tinkers: The Urbanization of an Itinerant People, by George Gmelch, 1997, 2nd ed. 1985.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.