| Indigenous Australians | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | 606,164 (2011)[1]

|

| Regions with significant populations | New South Wales 2.9% Queensland 4.2% Western Australia 3.8% Northern Territory 29.8% Victoria 0.85% South Australia 2.3% |

| Language | Several hundred indigenous Australian languages (many extinct or nearly so), Australian English, Australian Aboriginal English, Torres Strait Creole, Kriol |

| Religion | Various forms of Traditional belief systems based around the Dreamtime |

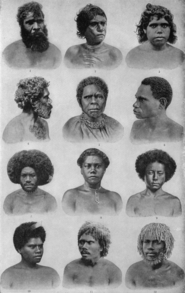

Indigenous Australians are descendants of the first human inhabitants of the Australian continent and its nearby islands. The term includes both the Torres Strait Islanders and the Aboriginal People, who together make up about 2.5 percent of Australia's population. The latter term is usually used to refer to those who live in mainland Australia, Tasmania, and some of the other adjacent islands. The Torres Strait Islanders are indigenous Australians who live in the Torres Strait Islands between Australia and New Guinea. Indigenous Australians are recognized to have arrived between 40,000 and 70,000 years ago.

The term "Indigenous Australians" encompasses many diverse communities and societies, and these are further divided into local communities with unique cultures. Fewer than 200 of the languages of these groups remain in use—all but 20 are highly endangered. It is estimated that prior to the arrival of British settlers the population of Indigenous Australians was approximately one million, now reduced to half that number, although that figure is considered high due to larger numbers of people with only partial Indigenous Australian ancestry being included. The distribution of people was similar to that of the current Australian population, with the majority living in the south east centered along the Murray River.

The arrival of the British colonists all but destroyed Indigenous Australian culture, reducing the population through disease and removing them from their homelands. Later efforts to assimilate them further destroyed their culture. Today, however, many are proud of their heritage, and there has been somewhat of a revival of indigenous art, music, poetry, dance, and sports. However, in many ways, the Aboriginal people remain an example of the suffering of one ethnic group caused by another.

Definitions

The word "aboriginal," appearing in English since at least the seventeenth century and meaning "first or earliest known, indigenous," (Latin Aborigines, from ab: from, and origo: origin, beginning), has been used in Australia to describe its indigenous peoples as early as 1789.[2] It soon became capitalized and employed as the common name to refer to all Indigenous Australians. Strictly speaking, "Aborigine" is the noun and "Aboriginal" the adjectival form; however the latter is often also employed to stand as a noun. Note that the use of "Aborigine(s)" or "Aboriginal(s)" in this sense as a noun has acquired negative, even derogatory connotations among some sectors of the community, who regard it as insensitive, and even offensive.[3] The more acceptable and correct expression is "Aboriginal Australians" or "Aboriginal people," though even this is sometimes regarded as an expression to be avoided because of its historical associations with colonialism. "Indigenous Australians" has found increasing acceptance, particularly since the 1980s.

Although the culture and lifestyle of Aboriginal groups have much in common, Aboriginal society is not a single entity. The diverse Aboriginal communities have different modes of subsistence, cultural practices, languages, and technologies. However, these peoples also share a larger set of traits, and are otherwise seen as being broadly related. A collective identity as Indigenous Australians is recognized and exists along names from the indigenous languages which are commonly used to identify groups based on regional geography and other affiliations. These include: Koori (or Koorie) in New South Wales and Victoria; Murri in Queensland; Noongar in southern Western Australia; Yamatji in Central Western Australia; Wangkai in the Western Australian Goldfields; Nunga in southern South Australia; Anangu in northern South Australia, and neighbouring parts of Western Australia and Northern Territory; Yapa in western central Northern Territory; Yolngu in eastern Arnhem Land (NT) and Palawah (or Pallawah) in Tasmania.

These larger groups may be further subdivided; for example, Anangu (meaning a person from Australia's central desert region) recognizes localized subdivisions such as Yankunytjatjara, Pitjantjatjara, Ngaanyatjara, Luritja, and Antikirinya.

The Torres Strait Islanders possess a heritage and cultural history distinct from mainland indigenous traditions; the eastern Torres Strait Islanders in particular are related to the Papuan peoples of New Guinea, and speak a Papuan language. Accordingly, they are not generally included under the designation "Aboriginal Australians." This has been another factor in the promotion of the more inclusive term "Indigenous Australians."

The term "blacks" has often been applied to Indigenous Australians. This owes rather more to racial stereotyping than ethnology, as it categorizes Indigenous Australians with the other black peoples of Asia and Africa, despite their relationships only being ones of very distant shared ancestry. In the 1970s, many Aboriginal activists, such as Gary Foley proudly embraced the term "black," and writer Kevin Gilbert's groundbreaking book from the time was entitled Living Black. In recent years young Indigenous Australians, particularly in urban areas have increasingly adopted aspects of black American and Afro-Caribbean culture, creating what has been described as a form of "black transnationalism."[4]

Surrounding Islands and Territories

Tiwi Islands and Groote Eylandt

The Tiwi islands are inhabited by the Tiwi, an Aboriginal people culturally and linguistically distinct from those of Arnhem Land on the mainland just across the water. They number around 2,500. Groote Eylandt belongs to the Anindilyakwa Aboriginal people, and is part of the Arnhem Land Aboriginal Reserve.

Tasmania

The Tasmanian Aborigines are thought to have first crossed into Tasmania approximately 40,000 years ago via a land bridge between the island and the rest of mainland Australia during an ice age. The original population, estimated at 8,000 people was reduced to a population of around 300 between 1803 and 1833, due in large part to the actions of British settlers. Almost all of the Tasmanian Aboriginal peoples today are descendants of two women: Fanny Cochrane Smith and Dolly Dalrymple. A woman named Truganini, who died in 1876, is generally considered to be the last first-generation tribal Tasmanian Aborigine.

Torres Strait Islanders

Six percent of Indigenous Australians identify themselves as fully as Torres Strait Islanders. A further four percent of Indigenous Australians identify themselves as having both Torres Strait Islander and Aboriginal heritage.[5]

More than 100 islands make up the Torres Strait Islands. The islands were annexed by Queensland in 1879.[6] There are 6,800 Torres Strait Islanders who live in the area of the Torres Strait, and 42,000 others who live outside of this area, mostly in the north of Queensland, such as in the coastal cities of Townsville and Cairns. Many organizations to do with Indigenous people in Australia are named "Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander," showing the importance of Torres Strait Islanders in Australia's indigenous population. The Torres Strait Islanders were not given official recognition by the Australian government until the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission was set up in 1990.

Languages

The indigenous languages of mainland Australia and Tasmania have not been shown to be related to any languages outside Australia. In the late eighteenth century, there were anywhere between 350 and 750 distinct groupings and a similar number of languages and dialects. At the start of the twenty-first century, fewer than 200 Indigenous Australian languages remain in use and all but about 20 of these are highly endangered. Linguists classify mainland Australian languages into two distinct groups, the Pama-Nyungan languages and the non-Pama-Nyungan. The Pama-Nyungan languages comprise the majority, covering most of Australia, and is a family of related languages. In the north, stretching from the Western Kimberley to the Gulf of Carpentaria, are found a number of groups of languages which have not been shown to be related to the Pama-Nyungan family or to each other: these are known as the non-Pama-Nyungan languages.

Many Australian Aboriginal cultures have or traditionally had a sign language counterpart to their spoken language. This appears to be connected with various taboos on speech between certain people within the community or at particular times, such as during a mourning period for women or during initiation ceremonies for men – unlike indigenous sign languages elsewhere which have been used as a lingua franca (Plains Indians sign language), or due to a high incidence of hereditary deafness in the community.

History

There is no clear or accepted origin of the indigenous people of Australia. It is thought that some Indigenous clans migrated to Australia through Southeast Asia though they are not demonstrably related to any known Polynesian population. There is genetic material, such as the M130 haplotype on the Y chromosome, in common with East Coast Africans and southern Indian Dravidian peoples (such as Tamils), indicating the probable original arc of migration from Africa.[7]

Migration to Australia

It is believed that first human migration to Australia was when this landmass formed part of the Sahul continent, connected to the island of New Guinea via a land bridge. It is also possible that people came by boat across the Timor Sea.

The exact timing of the arrival of the ancestors of the Indigenous Australians has been a matter of dispute among archaeologists. Mungo Man, whose remains were discovered in 1974 near Lake Mungo in New South Wales, is the oldest human to date found in Australia. Although the exact age of Mungo Man is in dispute, the best consensus is that he is at least 40,000 years old. Since Lake Mungo is in south-eastern Australia, many archaeologists have concluded that humans must have arrived in north-west Australia at least several thousand years earlier.

The most generally accepted date for first arrival is between 40,000 to 50,000 years ago. People reached Tasmania approximately 40,000 years ago, by migrating across a land bridge from the mainland which existed during the last ice age. After the seas rose about 12,000 years ago and covered the land bridge, the inhabitants there were isolated from the mainland until the arrival of British settlers.[8]

Other estimates for the arrival of the first people to Australia have been given as widely as from 30,000 to 68,000 years ago,[9] one suggesting that they left Africa 64,000 to 75,000 years ago.[10] This research showed that the ancestors of Aboriginal Australians reached Asia at least 24,000 years before a separate wave of migration that populated Europe and Asia, making Aboriginal Australians the oldest living population outside of Africa.[11]

Before British arrival

At the time of first European contact, it is estimated that a minimum of 315,000 and as many as 1 million people lived in Australia. Archaeological evidence suggests that the land could have sustained a population of 750,000.[12] Population levels are likely to have been largely stable for many thousands of years. The greatest population density was to be found in the southern and eastern regions of the continent, the Murray River valley in particular.

Impact of British settlement

In 1770, Lieutenant James Cook took possession of the east coast of Australia in the name of Great Britain and named it New South Wales. British colonization of Australia began in Sydney in 1788. The most immediate consequence of British settlement - within weeks of the first colonists' arrival - was a wave of epidemic diseases such as chickenpox, smallpox, influenza, and measles, which spread in advance of the frontier of settlement. The worst-hit communities were the ones with the greatest population densities, where disease could spread more readily. In the arid center of the continent, where small communities were spread over a vast area, the population decline was less marked.

The second consequence of British settlement was appropriation of land and water resources. The settlers took the view that Indigenous Australians were nomads with no concept of land ownership, who could be driven off land wanted for farming or grazing and who would be just as happy somewhere else. In fact the loss of traditional lands, food sources, and water resources was usually fatal, particularly to communities already weakened by disease. Additionally, indigenous groups had a deep spiritual and cultural connection to the land, so that in being forced to move away from traditional areas, cultural and spiritual practices necessary to the cohesion and well-being of the group could not be maintained. Unlike in New Zealand, no treaty was ever entered into with the indigenous peoples entitling the British to land ownership. Proximity to settlers also brought venereal disease, to which indigenous people had no tolerance and which greatly reduced indigenous fertility and birthrates. Settlers also brought alcohol, opium, and tobacco; substance abuse has remained a chronic problem for indigenous communities ever since.

The combination of disease, loss of land, and direct violence reduced the Aboriginal population by an estimated 90 percent between 1788 and 1900. The indigenous people in Tasmania were particularly hard hit. The last full-blood indigenous Tasmanian, Truganini, died in 1876, although a substantial part-indigenous community has survived.

In Tasmania some non-Aboriginal people were so horrified by what was happening to the Indigenous people they wrote to England seeking action to stop it from the British Government:

"There is black blood at this moment on the hands of individuals of good repute in the colony of New South Wales of which all the waters of New Holland would be insufficient to wash out the indelible stains."[13]

Although, some initial contacts between indigenous people and Europeans had been peaceful, starting with the Guugu Yimithirr people who met James Cook near Cooktown in 1770, a wave of massacres and resistance followed the frontier of British settlement. The number of violent deaths at the hands of white people is still the subject of debate, with a figure of around 10,000 - 20,000 deaths being advanced by historians such as Henry Reynolds; disease and dispossession were always major causes of indigenous deaths. By the 1870s all the fertile areas of Australia had been appropriated, and indigenous communities reduced to impoverished remnants living either on the fringes of Australian communities or on lands considered unsuitable for settlement.

As the Australian pastoral industry developed, major land management changes took place across the continent. The appropriation of prime land by colonists and the spread of European livestock over vast areas made a traditional indigenous lifestyle less viable, but also provided a ready alternative supply of fresh meat for those prepared to incur the settlers' anger by hunting livestock. The impact of disease and the settlers' industries had a profound impact on the Indigenous Australians' way of life. With the exception of a few in the remote interior, all surviving indigenous communities gradually became dependent on the settler population for their livelihood. In south-eastern Australia, during the 1850s, large numbers of white pastoral workers deserted employment on stations for the Australian gold rushes. Indigenous women, men and children became a significant source of labor. Most indigenous labor was unpaid; instead indigenous workers received rations in the form of food, clothing and other basic necessities. Stolen Wages cases have been raised against state governments, with limited success.

In the later nineteenth century, British settlers made their way north and into the interior, appropriating small but vital parts of the land for their own exclusive use (waterholes and soaks in particular), and introducing sheep, rabbits and cattle, all three of which ate out previously fertile areas and degraded the ability of the land to sustain the native animals that were vital to indigenous economies. Indigenous hunters would often spear sheep and cattle, incurring the wrath of graziers, after they replaced the native animals as a food source. As large sheep and cattle stations came to dominate northern Australia, indigenous workers were quickly recruited. Several other outback industries, notably pearling, also employed Aboriginal workers. In many areas Christian missions also provided food and clothing for indigenous communities, and also opened schools and orphanages for indigenous children. In some places colonial governments also provided some resources. Nevertheless, some indigenous communities in the most arid areas survived with their traditional lifestyles intact as late as the 1930s.

By the early twentieth century the indigenous population had declined to between 50,000 and 90,000, and the belief that the Indigenous Australians would soon die out was widely held, even among Australians sympathetic to their situation. But by about 1930, those indigenous people who had survived had acquired better resistance to imported diseases, and birthrates began to rise again as communities were able to adapt to changed circumstances.

By the end of World War II, many indigenous men had served in the military. They were among the few Indigenous Australians to have been granted citizenship; even those that had were obliged to carry papers, known in the vernacular as a "dog license," with them to prove it. However, Aboriginal pastoral workers in northern Australia remained unfree laborers, paid only small amounts of cash, in addition to rations, and severely restricted in their movements by regulations and/or police action. On May 1, 1946, Aboriginal station workers in the Pilbara region of Western Australia initiated the 1946 Pilbara strike and never returned to work. However, this protest came as modern technology and management techniques were starting to dramatically reduce the amount of labor required by pastoral enterprises. Mass layoffs across northern Australia followed the Federal Pastoral Industry Award of 1968, which required the payment of a minimum wage to Aboriginal station workers. Many of the workers and their families became refugees or fringe dwellers, living in camps on the outskirts of towns and cities.

By the end of the period white Australians were beginning to warm to indigenous culture. This can be seen in the Jindyworobak Movement of the 1950s, which although composed of white people took a positive view. The name itself is deliberately aboriginal, and may be seen as part of the distancing of white Australia from its European origins.

Emancipation

Under section 41 of the constitution Aborigines always had the legal right to vote in Commonwealth elections if their state granted them that right. From the time of Federation this meant that all Aborigines outside Queensland and Western Australia technically had a full legal right to vote. Point McLeay, a mission station near the mouth of the Murray River, got a polling station in the 1890s and Aboriginal men and women voted there in South Australian elections and voted for the first Commonwealth Parliament in 1901.

However, Sir Robert Garran, the first Solicitor-General, had interpreted section 41 to give Commonwealth rights only to those who were already State voters in 1902. Garran’s interpretation of section 41 was first challenged in 1924 by an Indian who had recently been accepted to vote by Victoria but rejected by the Commonwealth. He won the court case. Commonwealth legislation in 1962 specifically gave aborigines the right to vote in Commonwealth elections. Western Australia granted them the vote in that same year and Queensland followed suit in 1965.

Culture

There are a large number of tribal divisions and language groups in Aboriginal Australia, and, corresponding to this, a wide variety of diversity exists within cultural practices. However, there are some similarities between cultures.

Prior to the arrival of the British, the mode of life and material cultures varied greatly from region to region. While Torres Strait Island populations were agriculturalists who supplemented their diet through the acquisition of wild foods, the remainder of Indigenous Australians were hunter-gatherers or fishermen.

On mainland Australia no animal other than the dingo was domesticated, however domestic pigs were utilized by Torres Strait Islanders. The typical indigenous diet included a wide variety of foods, such kangaroo, emu, wombats, goanna, snakes, birds, many insects such as honey ants and witchetty grubs. Many varieties of plant foods such as taro, nuts, fruits, and berries were also eaten.

A primary tool used in hunting was the spear, launched by a woomera or spear-thrower in some locales. Boomerangs were also used by some mainland Indigenous peoples. The non-returnable boomerang (known more correctly as a throwing Stick), more powerful than the returning kind, could be used to injure or even kill a kangaroo.

Permanent villages were the norm for most Torres Strait Island communities. In some areas mainland Indigenous Australians also lived in semi-permanent villages, most usually in less arid areas where fishing could provide for a more settled existence. Most communities were semi-nomadic. Some localities were visited annually by Indigenous communities for thousands of years.

Some have suggested that the Last Glacial Maximum, was associated with a reduction in Aboriginal activity, and greater specialisation in the use of natural foodstuffs and products.[14] The Flandrian Transgression associated with sea-level rise may also have been periods of difficulty for affected groups.

A period of hunter-gatherer intensification occurred between 3000 and 1000 B.C.E. Intensification involved an increase in human manipulation of the environment, population growth, an increase in trade between groups, a more elaborate social structure, and other cultural changes. A shift in stone tool technology also occurred around this time. This was probably also associated with the introduction to the mainland of the Australian dingo.

Belief systems

Religious demography among Indigenous Australians is not conclusive because of flaws in the census. The 1996 census reported that almost 72 percent of Aborigines practiced some form of Christianity, and 16 percent listed no religion. The 2001 census contained no comparable updated data.[15]There has been an increase in the growth of Islam among the Indigenous Australian community.[16]

Indigenous Australia's oral tradition and spiritual values are based upon reverence for the land, the ancestral spirits which include the Rainbow Serpent, Baiame, Bunjil, and Yowie among others, and a belief in the dreamtime:

In the world's oldest continent the creative epoch known as the Dreamtime stretches back into a remote era in history when the creator ancestors known as the First Peoples travelled across the great southern land of Bandaiyan (Australia), creating and naming as they went.[17]

The Dreaming is at once both the ancient time of creation and the present day reality of Dreaming. One version of the Dreaming story runs as follows:

The whole world was asleep. Everything was quiet, nothing moved, nothing grew. The animals slept under the earth. One day the rainbow snake woke up and crawled to the surface of the earth. She pushed everything aside that was in her way. She wandered through the whole country and when she was tired she coiled up and slept. So she left her tracks. After she had been everywhere she went back and called the frogs. When they came out their tubby stomachs were full of water. The rainbow snake tickled them and the frogs laughed. The water poured out of their mouths and filled the tracks of the rainbow snake. That's how rivers and lakes were created. Then grass and trees began to grow and the earth filled with life.

Music

Aboriginal people developed unique instruments and folk styles. The yidaki or didgeridoo is commonly considered the national instrument of Aboriginal people, and it is claimed to be the world's oldest wind instrument. However, it was traditionally only played by Arnhem Land people, such as the Yolngu, and then only by the men. It has possibly been used by the people of the Kakadu region for 1,500 years. Clapping sticks are probably the more ubiquitous musical instrument, especially because they help maintain the rhythm for the song.

More recently, Aboriginal musicians have branched into rock and roll, hip hop, and reggae. One of the most well known modern bands is Yothu Yindi playing in a style which has been called Aboriginal rock. Contemporary aboriginal music is predominantly of the country and western genre. Most indigenous radio stations - particularly in metropolitan areas - serve a double purpose as the local country music station.

Art

Australia has a tradition of Aboriginal art which is thousands of years old, the best known forms being rock art and bark painting. These paintings usually consist of paint using earthly colors, specifically, from paint made from ochre. Traditionally, Aboriginals have painted stories from their dreamtime.

Modern Aboriginal artists continue the tradition using modern materials in their artworks. Aboriginal art is the most internationally recognizable form of Australian art. Several styles of Aboriginal art have developed in modern times, including the watercolor paintings of Albert Namatjira; the Hermannsburg School, and the acrylic Papunya Tula "dot art" movement. Painting is a large source of income for some Central Australian communities today.

Poetry

Australian Aboriginal poetry is found throughout Australia. It ranges from the sacred to the every day. Ronald M. Berndt has published traditional Aboriginal song-poetry in his book Three Faces of Love. [18] R.M.W. Dixon and M. Duwell have published two books dealing with sacred and every day poetry: The Honey Ant Men's Love Song and Little Eva at Moonlight Creek.

Traditional recreation

The Djabwurrung and Jardwadjali people of western Victoria once participated in the traditional game of Marn Grook, a type of football played with possum hide. The game is believed by some to have inspired Tom Wills, inventor of the code of Australian rules football, a popular Australian winter sport. Similarities between Marn Grook and Australian football include the unique skill of jumping to catch the ball or high "marking," which results in a free kick. The word "mark" may have originated in mumarki, which is "an Aboriginal word meaning catch" in a dialect of a Marn Grook playing tribe. Indeed, "Aussie Rules" has seen many indigenous players at elite football, and have produced some of the most exciting and skillful to play the modern game.

The contribution the Aboriginal people have made to the game is recognized by the annual AFL "Dreamtime at the 'G" match at the Melbourne Cricket Ground between Essendon and Richmond football clubs (the colors of the two clubs combine to form the colors of the Aboriginal flag, and many great players have come from these clubs, including Essendon's Michael Long and Richmond's Maurice Rioli).

Testifying to this abundance of indigenous talent, the Aboriginal All-Stars are an AFL-level all-Aboriginal football side competes against any one of the Australian Football League's current football teams in pre-season tests. The Clontarf Foundation and football academy is just one organization aimed at further developing aboriginal football talent. The Tiwi Bombers began playing in the Northern Territory Football League and became the first and only all-Aboriginal side to compete in a major Australian competition.

Contemporary Aborigines

The Indigenous Australian population is a mostly urbanized demographic, but a substantial number (27 percent) live in remote settlements often located on the site of former church missions.[19] The health and economic difficulties facing both groups are substantial. Both the remote and urban populations have adverse ratings on a number of social indicators, including health, education, unemployment, poverty and crime.[20] In 2004 Prime Minister John Howard initiated contracts with Aboriginal communities, where substantial financial benefits are available in return for commitments such as ensuring children wash regularly and attend school. These contracts are known as Shared Responsibility Agreements. This sees a political shift from 'self determination' for Aboriginal communities to 'mutual obligation,'[21] which has been criticized as a "paternalistic and dictatorial arrangement."[22]

Population

The Australian Bureau of Statistics 2005 snapshot of Australia shows the indigenous population has grown at twice the rate of the overall population since 1996 when the indigenous population stood at 283,000. As at June 2001, the Australian Bureau of Statistics estimated the total resident indigenous population to be 458,520 (2.4 percent of Australia's total), 90 percent of whom identified as Aboriginal, 6 percent Torres Strait Islander, and the remaining 4 percent being of dual Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander parentage. The proportion of indigenous adults married to non-indigenous spouses was 69 percent, up from 46 percent in 1986, and the majority of Aborigines are now of mixed descent. Much of the increase since 1996 can be attributed to higher rates of people identifying themselves as Aborigines and changed definitions of aboriginality. The 2006 Census confirmed that the Aboriginal population had actually declined to approximately 200,000.

While the State with the largest total Aboriginal population is New South Wales (134,888), as a percentage this constitutes only 2.1 percent of the overall population of the State. The Northern Territory has the largest Aboriginal population in percentage terms for a State or Territory, with 28.8 percent. All the other States and Territories have less than 4 percent of their total populations identifying as Aboriginal; Victoria has the lowest percentage (0.6 percent).

The vast majority of Aboriginal people do not live in separate communities away from the rest of the Australian population: in 2001 about 30 percent were living in major cities and another 43 percent in or close to rural towns, an increase from the 46 percent living in urban areas in 1971. The populations in the eastern states are more likely to be urbanized, whereas many of the populations of the western states live in remote areas, closer to a traditional Aboriginal way of life.

Health

In 2002 data collected on health status reported that Indigenous Australians were twice as likely as non-indigenous people to report their health as fair/poor and one-and-a-half times more likely to have a disability or long-term health condition (after adjusting for demographic structures).[19] In 1996-2001, the life expectancy of an Indigenous Australian was 59.4 years for males and, in 2004-05, 65.0 years for females,[23] approximately 17 years lower than the Australian average.[19]

The following factors have been at least partially implicated in the racial inequality in life expectancy:[24]

- poverty (low income)

- discrimination

- poor education

- substance abuse (smoking, alcohol, illicit drugs)

- for remote communities poor access to health services including immunization

- for urbanized Indigenous Australians, social pressures which prevent access to health services

- cultural differences resulting in poor communication between Indigenous Australians and health workers.

- exposure to violence

Additional problems are created by the reluctance of many rural indigenous people to leave their homelands to access medical treatment in larger urban areas, particularly when they have need for on-going treatments such as dialysis.[24]

Successive Federal Governments have responded to the problem by implementing programs such as the Office of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health (OATSIH). There have been some small successes, such as the reduction of infant mortality since the 1970s (down to twice the non-Indigenous levels in 1996-2001),[24] effected by bringing health services into indigenous communities, but on the whole the problem remains unsolved.

Education

Indigenous students as a group leave school earlier, and live with a lower standard of education, compared with their non-indigenous peers. Although the situation is slowly improving (with significant gains between 1994 and 2004),[19] both the levels of participation in education and training among Indigenous Australians and their levels of attainment remain well below those of non-Indigenous Australians.

In response to this problem, the Commonwealth Government formulated a National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Policy. A number of government initiatives have resulted.[25]

Crime

An Indigenous Australian is 11 times more likely to be in prison than a non-Indigenous Australian, and in June 2004, 21 percent of prisoners in Australia were Indigenous.[26]

Violent crime, including domestic and sexual abuse, is a problem in many communities. Indigenous Australians are twice as likely to be a victim of violence than non-Indigenous Australians, with 24 percent of Indigenous Australians reported being a victim of violence in 2001. This is consistent with hospitalization data showing higher rates of injury due to assault.[26]

Australia-wide, Indigenous Australian children are 20-fold overrepresented in the juvenile corrective service and 20-fold more likely to be involved in child abuse and neglect cases.[24]

Unemployment and housing

According to the 2001 Census, an Indigenous Australian is almost three times more likely to be unemployed (20.0 percent unemployment) than a non-Indigenous Australian (7.6 percent). The difference is not solely due to the increased proportion of Indigenous Australians living in rural communities, because unemployment is higher in Indigenous Australian populations living in urban centers.[27] The average household income for Indigenous Australian populations is 60 percent of the non-Indigenous average.[19] Indigenous Australians are 6-fold more likely to be homeless, 15-fold more likely to be living in improvised dwellings, and 25-fold more likely to be living with 10 or more people.[24]

Substance abuse

A number of Indigenous communities suffer from a range of health and social problems associated with substance abuse of both legal and illegal drugs.

Alcohol consumption within certain Indigenous communities is seen as a significant issue, as are the domestic violence and associated issues resulting from the behavior. To combat the problem, a number of programs to prevent or mitigate against alcohol abuse have been attempted in different regions, many initiated from within the communities themselves. These strategies include such actions as the declaration of "Dry Zones" within indigenous communities, prohibition and restriction on point-of-sale access, and community policing and licensing. Some communities (particularly in the Northern Territory) have introduced kava as a safer alternative to alcohol, as over-indulgence in kava produces sleepiness, in contrast to the violence that can result from over-indulgence in alcohol.

These and other measures have met with variable success, and while a number of communities have seen decreases in associated social problems caused by excessive drinking, others continue to struggle with the issue and it remains an ongoing concern.

Political representation

Indigenous Australians gained the right to vote in Federal elections in 1965, but it was not until 1967 that they were counted in the distribution of electoral seats and the Australian government gained the power to legislate for Aborigines. Indigenous Australians have been elected to the Australian Parliament, Neville Bonner (1971-1983) and Aden Ridgeway (1999-2005).

Native Title to land

When the British began to colonize Australia, they took over the land without compensation to the indigenous people. The legal principle governing British and then Australian law regarding Aborigines’ land was that of terra nullius – that the land could legitimately be taken over as the indigenous people had no laws regarding ownership of land. In 1971, in the controversial Gove land rights case, Justice Blackburn ruled that Australia had been terra nullius before European settlement, and that there was no such thing as native title in Australian law.[28]

In 1992, however, the Mabo decision overturned this position. This landmark High Court of Australia decision recognized native title in Australia for the first time, rejecting the doctrine of terra nullius, in favor of the common law doctrine of aboriginal title.[29]

In response to the judgment, the Parliament of Australia enacted the Native Title Act 1993 (NTA).[30] In 1998, The Native Title Amendment Act 1998 created the Native Title Tribunal[31] and placed restrictions on land rights claims.

As a result of these developments some Aborigines have succeeded in securing ownership titles to their land.

Prominent Indigenous Australians

There have been many distinguished Indigenous Australians, in politics, sports, the arts, and other areas. These include:

- Arthur Beetson, captain of the Australian national rugby league team

- Neville Bonner, politician

- Ernie Dingo, comedian, actor and presenter

- Mark Ella, rugby union player

- Cathy Freeman, Olympic athlete

- Evonne Goolagong, tennis Grand Slam winner

- David Gulpilil, actor

- Albert Namatjira, painter

- Sir Douglas Nicholls, Australian rules footballer, clergyman and Governor of South Australia,

- Oodgeroo Noonuccal, poet, author, playwright, civil rights activist, educator

- Lowitja O'Donoghue, nurse and activist

- Johnathan Thurston, rugby league player

- Charles Perkins, soccer player, sports administrator and civil rights activist

- Mandawuy Yunupingu, singer and songwriter

Notes

- ↑ Estimates of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians Australian Bureau of Statistics, June 2011. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ aborigine Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, Indigenous. "Editing Aboriginal voices." Bruderlin MacLean Publishing Services.

- ↑ Peter Dunbar-Hall, Deadly Sounds, Deadly Places: Contemporary Aboriginal Music In Australia (University of New South Wales Press, 2004, ISBN 0868406228), 120-121.

- ↑ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population Year Book Australia, 2004, Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Places - Torres Strait Islands ABC Radio Australia website. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Amy Werner, Genographic Researchers in Australia Uncover Unique Branches of the Human Family Tree National Geographic, December 16, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Derek John Mulvaney and Johan Kamminga, Prehistory of Australia (Washington, DC, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999).

- ↑ J.M. Bowler, et al, Letters: New ages for human occupation and climatic change at Lake Mungo, Australia Nature 421(February 20, 2003): 837-840. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Australian Geographic staff, DNA confirms Aboriginal culture one of Earth's oldest Australian Geographic (September 23, 2011). Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Morten Rasmussen, et. al., An Aboriginal Australian Genome Reveals Separate Human Dispersals into Asia Science (September 22, 2011). Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander population Year Book 2007, Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ John Dunmore Lang, An Historical and Statistical Account of New South Wales: Both as a Penal Settlement and as a British Colony, third ed. (1834; London: Routledge, 1840), 38

- ↑ Josephine Flood, Archaeology of the Dreamtime (Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1995, ISBN 0207184488),

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics - Religion Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Phil Mercer, Aborigines turn to Islam BBC News (March 31, 2003). Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Munya Andrews, The Seven Sisters of the Pleiades: Stories from Around the World (North Melbourne: Spinifex Press, 2004), 424

- ↑ Ronald M. Berndt, Three Faces of Love (Nelson 1976).

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 19.3 19.4 Selected findings from the 2002 National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Survey Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Year Book Australia 2005 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Ian P.S. Anderson, Mutual obligation, shared responsibility agreements & indigenous health strategy Australia and New Zealand Health Policy 3(10) (2006). Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Larissa Behrendt Nothing mutual about denying Aborigines a voice The Age newspaper (December 8, 2004). Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ The health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women: A snapshot, 2004-05 Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 The health and welfare of Australia's Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples 2003 Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Education Policy, 1989 Australian Government.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Crime and Justice: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People: Contact with the Law ABS Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Social Trends, 2005. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Labour force status of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples Year Book Australia, 2004, Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd (1971) 17 FLR 141 The Agreements, Treaties and Negotiated Settlements (ATNS) project. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Mabo and Others v. Queensland (No. 2) (June 2, 1992). Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Native Title Act 1993 Commonwealth Consolidated Acts. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- ↑ Native Title Amendment Act 1998 Retrieved March 16, 2017.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Andrews, Munya. The Seven Sisters of the Pleiades: Stories from Around the World. North Melbourne: Spinifex Press, 2005. ISBN 1876756454

- Berndt, Ronald M. Three Faces of Love. Thomas Nelson, 1976. ISBN 978-0170051088

- Berndt, Ronald M. Australian Aboriginal Religion. Iconography of Religions Section 5 - Australia, No 3, 1997. ISBN 9004037276

- Berndt, Ronald M. and Catherine H. Berndt. The Speaking Land: Myth and Story in Aboriginal Australia. Inner Traditions, 1994. ISBN 0892815183

- Clarke, Philip. Where the Ancestors Walked: Australia as an Aboriginal Landscape. Allen & Unwin Academic, 2004. ISBN 1741140706

- Dixon, R.M.W. The Rise and Fall of Languages. Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0521626544

- Dunbar-Hall, Peter. Deadly Sounds, Deadly Places: Contemporary Aboriginal Music In Australia. University of New South Wales Press, 2004. ISBN 0868406228

- Flood, Josephine. Archaeology of the Dreamtime, 2nd Revised ed. Sydney: Angus & Robertson, 1995. ISBN 0207184488

- Lang, John Dunmore. An historical and statistical account of New South Wales,: Both as a penal settlement and as a British colony, Third ed. London: Routledge, 1840 (orig. 1834). ASIN B00087UQC2

- Mulvaney, Derek John, and Johan Kamminga. Prehistory of Australia. Washington, DC: Smithsonian, 1999. ISBN 1560988045

- Sutton, Peter. Dreamings: The Art of Aboriginal Australia. George Braziller, 1997. ISBN 0807612014

External links

All links retrieved August 22, 2023.

- Aboriginal Studies Virtual Library

- Aborigines win 'native title' over Perth

- Australia's National Indigenous Times largest circulating Indigenous Affairs Newspaper.

- Latest Indigenous news from ABC News Online

- Law and justice statistics - Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people: a snapshot, 2006 Australian Bureau of Statistics, May 14, 2007.

- Reconciliation Australia

- Aboriginal people Survival International

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.