Chickenpox

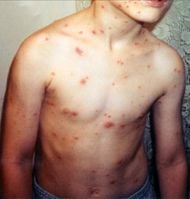

Child with varicella disease | |

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | B01 |

| ICD-O: | |

| ICD-9 | 052 |

| OMIM | [1] |

| MedlinePlus | 001592 |

| eMedicine | ped/2385 |

| DiseasesDB | 29118 |

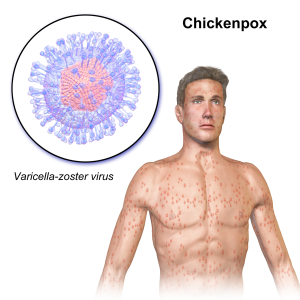

Chickenpox (or chicken pox), also known as varicella, is a common and very highly contagious viral disease caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VSZ). It is classically one of the childhood infectious diseases caught and survived by almost every child, although currently there is a vaccine.

Following primary infection, there is usually lifelong protective immunity from further episodes of chickenpox. Recurrent chickenpox, commonly known as shingles, is fairly rare but more likely in people with compromised immune systems.

As uncomfortable as chicken pox is—with fever and often hundreds of itchy blisters that proceed to open, but rarely scarring sores—there was a time that some mothers would deliberately expose their young daughters to chickenpox. This is because of the potential complications should a pregnant women get chickenpox, and the view that it is better to go through limited suffering for the sake of future benefit. Today, an easier course if available with the availability of a vaccine that is highly effective for preventing chickenpox, and especially for the most severe cases.

Overview

Varicella-zoster virus

Chickenpox is caused by the varicella-zoster virus (VZV), also known as human herpes virus 3 (HHV-3), one of the eight herpes viruses known to affect humans.

Multiple names are used to refer to same virus, creating some confusion. Varicella virus, zoster virus, human herpes 3 (HHV-3), and Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV) all refer to the same viral pathogen.

VZV is closely related to the herpes simplex viruses (HSV), sharing much genome homology. The known envelope glycoproteins (gB, gC, gE, gH, gI, gK, gL) correspond with those in HSV, however there is no equivalent of HSV gD. VZV virons are spherical and 150-200 nm in diameter. Their lipid envelope encloses the nucleocapsid of 162 capsomeres arranged in a hexagonal form. Its DNA is a single, linear, double-stranded molecule, 125,000 nt long.

The virus is very susceptible to disinfectants, notably sodium hypochlorite. Within the body it can be treated by a number of drugs and therapeutic agents, including aciclovir, zoster-immune globulin (ZIG), and vidarabine.

Chickenpox and shingles

The initial infection with the varicella-zoster virus (the primary VZV infection) results in chickenpox (varicella), which may rarely result in complications including VZV encephalitis or pneumonia. Even when clinical symptoms of varicella have resolved, VZV remains dormant in the nervous system of the host in the trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia.

In about 10-20 percent of cases, VZV reactivates later in life, producing a disease known as shingles, herpes zoster, or simply zoster. These localized eruptions occur particularly in people with compromised immune systems, such as the elderly, and perhaps even those suffering sunburn. Serious complications of shingles include post-herpetic neuralgia, zoster multiplex, myelitis, herpes ophthalmicus, or zoster sine herpete.

Chickenpox is a highly contagious disease that spreads from person to person by direct contact or through the air from an infected person's coughing or sneezing. Touching the fluid from a chickenpox blister can also spread the disease, including indirectly via an article of clothing with fresh fluid. The virus has a 10-21 day incubation period before symptoms appear. A person with chickenpox is contagious from 1-2 days before the rash appears until all blisters have formed scabs. This may take 5-10 days (NZDS 2016; CDC 2021).

Before the 1995 introduction of the varicella vaccine, Varivax, virtually all children born each year in the United States contracted chickenpox, with a rate of only about five of every 1,000 needing hospitalization and about 100 deaths a year (Longe 2006). By ages nine or ten, about 80 to 90 percent of American children were infected, and adults counted for less than five percent of all cases, with about 90 percent immune to the virus (Longe 2005). However, adults are more likely than children to suffer dangerous consequences, and about half of all deaths occur among adults (Knapp and Wilson 2005).

Although chickenpox is rarely fatal (usually from varicella pneumonia), pregnant women and those with a suppressed immune system encounter greater risks. Pregnant women not known to be immune and who come into contact with chickenpox may need urgent treatment as the virus can cause serious problems for the baby. This is less of an issue after 20 weeks.

Signs and symptoms

Chickenpox commonly starts without warning or with a mild fever and discomfort (Longe 2006). There may be conjunctival (membrane covering white of eye and inside eyelid) and catarrhal (runny nose) symptoms and then characteristic spots appearing in two or three waves. These small red spots appear on the scalp, neck, or upper half of the trunk, rather than the hands, and after 12 to 24 hours become itchy, raw, fluid-filled bumps (pox, "pocks"), small open sores that heal mostly without scarring. They appear in crops for two to five days (Longe 2006).

The chickenpox lesions (blisters) start as a 2–4 mm red papule, which develops an irregular outline (rose petal). A thin-walled, clear vesicle (dew drop) develops on top of the area of redness. This "dew drop on a rose petal" lesion is very characteristic for chickenpox. After about 8–12 hours, the fluid in the vesicle gets cloudy and the vesicle breaks leaving a crust. The fluid is highly contagious, but once the lesion crusts over, it is not considered contagious. The crust usually falls off after 7 days, sometimes leaving a crater-like scar.

Although one lesion goes through this complete cycle in about 7 days, another hallmark of chickenpox is the fact that new lesions crop up every day for several days. One area of skin may have lesions of a variety of stages (Longe 2006). It may take about a week until new lesions stop appearing and existing lesions crust over. Children are not to be sent back to school until all lesions have crusted over at which point they are no longer considered contagious (Iannelli 2021).

Some people only develop a few blisters, but in most cases the number reaches 250-500 (Knapp and Wilson 2005). The blisters may cover much of the skin and in some cases may appear inside the mouth, nose, ears, rectum, or vagina (Longe 2005). The blisters can itch very little or can be extremely itchy.

Second infections with chickenpox occur in immunocompetent individuals, but are uncommon. Such second infections are rarely severe. A soundly-based conjecture being carefully assessed in countries with low prevalence of chickenpox due to immunization, low birth rates, and increased separation is that immunity has been reinforced by subclinical challenges and this is now less common.

Shingles, a reactivation of chickenpox, may also be a source of the virus for susceptible children and adults.

The course of chickenpox will vary with each child, but a child generally will be sick with chickenpox for about 4-7 days. New blisters usually stop appearing by the 5th day, most are crusted by the 6th day, and most scabs are gone within 20 days after the rash begins. If complications set in, however, the recovery period may be even longer.

These are the most common symptoms of chicken pox:

- Mild fever. The fever varies between 101°F to 105°F and returns to normal when the blisters have disappeared.

- backache

- headache

- sore throat

- a rash (red spots)

- blisters filled with fluid

A doctor should be consulted if the child's fever goes above 102°F or takes more than four days to disappear, the blisters appear infected, or the child appears nervous, confused, unresponsive, unusually sleepy, complains of stiff neck or severe headache, shows poor balance, has trouble breathing, is vomiting repeatedly, finds bright lights hard to look at, or is having convulsions (Longe 2006).

Prognosis and treatment

Treatment usually takes place in the home, with a focus on reducing discomfort and fever (Longe 2006). Chickenpox infection tends to be milder the younger a child is and symptomatic treatment, with a little sodium bicarbonate in baths or antihistamine medication to ease itching (Somekh et al. 2002), and paracetamol (acetaminophen) to reduce fever, are widely used. Ibuprofen can also be used on advice of a doctor. Aspirin should not be used because they can increase the probability of developing Reye's syndrome. Antibiotics are ineffective since it is viral in nature, rather than bacterial. There is no evidence to support the topical application of calamine lotion, a topical barrier preparation containing zinc oxide in spite of its wide usage and excellent safety profile (Tebruegge et al. 2006).

It is important to maintain good hygiene and daily cleaning of skin with warm water to avoid secondary bacterial infection. Scratching the blisters can cause them to become infected and should be avoided. Mittens or socks on the hands of infants can help protect against scratching (Longe 2006).

Infection of the virus in otherwise healthy adults tends to be more severe and active; treatment with antiviral drugs (e.g. acyclovir) is generally advised. Patients of any age with depressed immune systems or extensive eczema are at risk of more severe disease and should also be treated with antiviral medication. In the United States, 55 percent of chickenpox deaths are in the over-20 age group.

Congenital defects in babies

These may occur if the child's mother was exposed to VZV during pregnancy. Effects on the fetus may be minimal in nature, but physical deformities range in severity from under developed toes and fingers, to severe anal and bladder malformation. Possible problems include:

- Damage to brain: Encephalitis, microcephaly, hydrocephaly, aplasia of brain

- Damage to the eye (optic stalk, optic cap, and lens vesicles): Microphthalmia, cataracts, chorioretinitis, optic atrophy.

- Other neurological disorder: Damage to cervical and lumbosacral spinal cord, motor/sensory deficits, absent deep tendon reflexes, anisocoria/Horner's syndrome

- Damage to body: Hypoplasia of upper/lower extremities, anal and bladder sphincter dysfunction

- Skin disorders: (Cicatricial) skin lesions, hypopigmentation

Vaccination

A varicella vaccine has been available since 1995, to inoculate against the disease. Some countries and states in the United States require the varicella vaccination or an exemption for matriculation in elementary school. Protection is not lifelong and further vaccination is necessary five years after the initial immunization (Chaves et al. 2007).

In the United Kingdom, varicella antibodies are measured as part of the routine of prenatal care, and by 2005, all NHS health care personnel had determined their immunity and been immunized if they were non-immune and have direct patient contact. Population-based immunization against varicella is not otherwise practiced in the UK, because of lack of evidence of lasting efficacy or public health benefit.

History

One history of medicine book credits Giovanni Filippo (1510–1580) of Palermo with the first description of varicella (chickenpox). Subsequently in the 1600s, an English physician named Richard Morton described what he thought a mild form of smallpox as "chicken pox." Later, in 1767, a physician named William Heberden, also from England, was the first physician to clearly demonstrate that chickenpox was different from smallpox. However, it is believed the name chickenpox was commonly used in earlier centuries before doctors identified the disease.

There are many explanations offered for the origin of the name "chickenpox:"

- Samuel Johnson suggested that the disease was "no very great danger," thus a "chicken" version of the pox;

- the specks that appear looked as though the skin was pecked by chickens;

- the disease was named after chick peas, from a supposed similarity in size of the seed to the lesions;

- the term reflects a corruption of the Old English word giccin, which meant "itching."

As "pox" also means curse, in medieval times some believed it was a plague brought on to curse children by the use of black magic.

From ancient times, neem has been used by people in India to alleviate the external symptoms of itching and to minimize scarring. Neem baths (neem leaves and a dash of turmeric powder in water) are commonly given for the duration.

During the medieval era, oatmeal was discovered to soothe the sores, and oatmeal baths are today still commonly given to relieve itching.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Aronson, J. 2000. When I use a word...chickenpox. BMJ 321(7262): 682. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- Iannelli, V. 2021. Symptoms of Chickenpox Verywell health. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2021. Chickenpox (Varicella): Transmission. CDC. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2005. Varicella-related deaths: United States, January 2003-June 2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 54(11): 272-274. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- Chaves, S. S., P. Gargiullo, J. X. Zhang, and et al. 2007. Loss of vaccine-induced immunity to varicella over time. N Engl J Med 356(11): 1121-1129.

- Krapp, Kristine M., and Jeffrey Wilson. 2005. The Gale Encyclopedia of Children's Health: Infancy Through Adolescence. Detroit: Thomson Gale. ISBN 0787692417

- Longe, J. L. 2005. The Gale Encyclopedia of Alternative Medicine. Farmington Hills, Mich: Thomson/Gale. ISBN 0787693960

- Longe, J. L. 2006. The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine. Detroit: Thomson Gale. ISBN 1414403682

- New Zealand Dermatological Society (NZDS). 2016. Chickenpox (varicella). DermNet NZ. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- Somekh, E., I. Dalal, T. Shohat, G. M. Ginsberg, and O. Romano. 2002. The burden of uncomplicated cases of chickenpox in Israel. J. Infect. 45(1): 54-57. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- Tebruegge, M., M. Kuruvilla, and I. Margarson. 2006. Does the use of calamine or antihistamine provide symptomatic relief from pruritus in children with varicella zoster infection?. Arch. Dis. Child. 91(12): 1035-1036. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

- Thomas, S. J., A. J. Wheeler, and A. Hall. 2002. Contacts with varicella or with children and protection against herpes zoster in adults: A case-control study. Lancet 360(9334): 678-682. Retrieved March 9, 2022.

External links

All links retrieved December 10, 2023.

- Chickenpox Cleveland Clinic.

- Chickenpox Mayo Clinic.

| Viral diseases (A80-B34, 042-079) | |

|---|---|

| Viral infections of the central nervous system | Poliomyelitis (Post-polio syndrome) - Subacute sclerosing panencephalitis - Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy - Rabies - Encephalitis lethargica - Lymphocytic choriomeningitis - Tick-borne meningoencephalitis - Tropical spastic paraparesis |

| Arthropod-borne viral fevers and viral haemorrhagic fevers | Dengue fever - Chikungunya - Rift Valley fever - Yellow fever - Argentine hemorrhagic fever - Bolivian hemorrhagic fever - Lassa fever - Crimean-Congo hemorrhagic fever - Omsk hemorrhagic fever - Kyasanur forest disease - Marburg hemorrhagic fever - Ebola |

| Viral infections characterized by skin and mucous membrane lesions | Herpes simplex - Chickenpox - Herpes zoster - Smallpox - Monkeypox - Measles - Rubella - Plantar wart - Cowpox - Vaccinia - Molluscum contagiosum - Roseola - Fifth disease - Hand, foot and mouth disease - Foot-and-mouth disease |

| Viral hepatitis | Hepatitis A - Hepatitis B - Hepatitis C - Hepatitis E |

| Viral infections of the respiratory system | Avian flu - Acute viral nasopharyngitis - Infectious mononucleosis - Influenza - Viral pneumonia |

| Other viral diseases | HIV (AIDS, AIDS dementia complex) - Cytomegalovirus - Mumps - Bornholm disease |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.