Minotaur

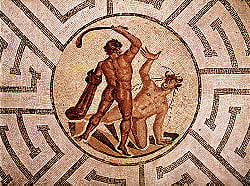

In Greek mythology, the Minotaur (Greek: Μινόταυρος, Minótauros) was a creature that was part man and part bull.[1] It dwelt at the center of the Labyrinth, which was an elaborate maze-like construction built for King Minos of Crete and designed by the architect Daedalus to hold the Minotaur. He and his son Icarus were ordered to build it. The historical site of Knossos is usually identified as the site of the labyrinth. The Minotaur was eventually killed by Theseus.

"Minotaur" is Greek for "Bull of Minos." The bull was known in Crete as Asterion, a name shared with Minos's foster father.

Birth and appearance

The literary myth satisfied a Hellenic interpretation of Minoan myth and ritual. According to this, before Minos became king, he asked the Greek god Poseidon for a sign, to assure him that he, and not his brother, was to receive the throne (other accounts say that he boasted that the gods wanted him to be king). Poseidon agreed to send a white bull as a sign, on condition Minos would sacrifice the bull to the god in return. Indeed, a bull of unmatched beauty came out of the sea. King Minos, after seeing it, found it so beautiful that he instead sacrificed another bull, hoping that Poseidon would not notice. Poseidon was enraged when he realized what had been done, so he caused Minos's wife, Pasiphaë, to fall deeply in love with the bull. Pasiphaë tried to seduce the bull without success, then she requested some help from Daedalus the greatest architect from Creta. Daedalus built a wooden cow, the cow was hollow allowing Pasiphaë to hide inside. The queen came back inside the wooden cow and the bull confused by the perfection of the costume he was conquered. The result of this union was the Minotaur (the Bull of Minos), who some say bore the proper name Asterius (the "Starry One"). In some accounts, the white bull went on to become the Cretan Bull captured by Heracles as one of his labours.

The Minotaur had the body of a man and the head and tail of a bull.[2] Pasiphaë nursed him in his infancy, but he grew and became ferocious. Minos, after getting advice from the Oracle at Delphi, had Daedalus construct a gigantic labyrinth to hold the Minotaur. Its location was near Minos' palace in Knossos.

The price that brought Theseus

Now it happened that Androgeus, son of Minos, had been killed by the Athenians, who were jealous of the victories he had won at the Panathenaic festival. Others say he was killed at Marathon by the Cretan bull, his mother's former taurine lover, which Aegeus, king of Athens, had commanded him to slay. The common tradition is that Minos waged war to avenge the death of his son, and won. However, Catullus, in his account of the Minotaur's birth,[3] refers to another version in which Athens was "compelled by the cruel plague to pay penalties for the killing of Androgeon." In this version, the Athenians are made to ask Minos what they can do to stop a terrible plague that has come upon them, and he was thus given power to make demands of them. In either case, Minos required that seven Athenian youths and seven maidens, drawn by lots, be sent every ninth year (some accounts say every year) to be devoured by the Minotaur.

When the third sacrifice came round, Theseus volunteered to go to slay the monster. He promised to his father, Aegeus, that he would put up a white sail on his journey back home if he was successful. Ariadne, the daughter of Minos, fell in love with Theseus and helped him get out of the labyrinth. In most accounts she gives him a ball of thread, allowing him to retrace his path. Theseus killed the Minotaur and led the other Athenians back out of the labyrinth.[4]

Theseus took Ariadne with him from Crete, but abandoned her enroute to Athens (Generally this is said to happen on the island of Naxos). According to Homer, she was killed by Artemis upon the testimony of Dionysus. However, later sources report that Theseus abandoned her as she slept on the island of Naxos, and there became the bride of Dionysus. The epiphany of Dionysus to the sleeping Ariadne became a common theme in Greek and Roman art, and in some of these images Theseus is shown running away. This story is also recounted in Catullus.

On his return trip, Theseus forgot to change the black sails of mourning for white sails of success, so his father, overcome with grief, leapt off the clifftop from which he had kept watch for his son's return every day since Theseus had departed into the sea. The name of the "Aegean" sea is said to derive from this event.

Minos, angry that Theseus was able to escape, imprisoned Daedalus and his son Icarus in a tall tower. They were able to escape by building wings for themselves with the feathers of birds that flew by, but Icarus died during the escape as he flew too high (in hope of seeing Apollo in his sun chariot) and the wax that held the feathers in the wing melted in the heat of the sun.

Interpretations

The contest between Theseus and the Minotaur was frequently represented in Greek art. A Knossian didrachm exhibits on one side the labyrinth, on the other the Minotaur surrounded by a semicircle of small balls, probably intended for stars; it is to be noted that one of the monster's names was Asterius.

The ruins of Minos' palace at Knossos have been found, but the labyrinth hasn't. The enormous number of rooms, staircases and corridors in the palace has led archaeologists to believe that the palace itself was the source of the labyrinth myth. Homer, describing the shield of Achilles, remarked that the labyrinth was Ariadne's ceremonial dancing ground.

Some modern mythologists regard the Minotaur as a solar personification and a Minoan adaptation of the Baal-Moloch of the Phoenicians. The slaying of the Minotaur by Theseus in that case indicates the breaking of Athenian tributary relations with Minoan Crete.

According to A.B. Cook, Minos and Minotaur are only different forms of the same personage, representing the sun-god of the Cretans, who depicted the sun as a bull. He and J. G. Frazer both explain Pasiphae's union with the bull as a sacred ceremony, at which the queen of Knossos was wedded to a bull-formed god, just as the wife of the Tyrant in Athens was wedded to Dionysus. E. Pottier, who does not dispute the historical personality of Minos, in view of the story of Phalaris, considers it probable that in Crete (where a bull-cult may have existed by the side of that of the double axe) victims were tortured by being shut up in the belly of a red-hot brazen bull. The story of Talos, the Cretan man of brass, who heated himself red-hot and clasped strangers in his embrace as soon as they landed on the island, is probably of similar origin.

A historical explanation of the myth refers to the time when Crete was the main political and cultural potency in the Aegean Sea. As the fledgling Athens (and probably other continental Greek cities) was under tribute to Crete, it can be assumed that such tribute included young men and women for sacrifice. This ceremony was performed by a priest disguised with a bull head or mask, thus explaining the imagery of the Minotaur. It may also be that this priest was son to Minos.

Once continental Greece was free from Crete's dominance, the myth of the Minotaur worked to distance the forming religious consciousness of the Hellene poleis from Minoan beliefs.

Notes

- ↑ semibovumque virem; semivirumque bovem, according to Ovid, Ars Amatoria 2.24, one of the three lines that his friends would have deleted from his work, and one of the three that he, selecting independently, would preserve at all cost, in the apocryphal anecdote told by Albinovanus Pedo. (noted by J. S. Rusten, "Ovid, Empedocles and the Minotau" The American Journal of Philology 103.3 (Autumn 1982, pp. 332-333) p. 332.

- ↑ One of the figurations assumed by the river god Achelous in wooing Deianira is as a man with the head of a bull, according to Sophocles' Trachiniai.

- ↑ Carmen 64.

- ↑ Plutarch, Theseus, 15—19; Diodorus Siculus i. I6, iv. 61; Bibliotheke iii. 1,15

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Minotaur in Greek Myth source Greek texts and art

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.