Difference between revisions of "Ideology" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

The ideologies of the dominant class of a society ("dominant ideology") are proposed to all members of that society in order to make the ruling class' interests appear to be the interests of all. Ruled class are "educated" to share and believe "dominant ideology" as if it is good for all or universally valid claims. [[György Lukács]] (1885 – 1971) described this as a projection of the [[class consciousness]] of the ruling class, while [[Antonio Gramsci]] (1891 – 1937) advanced the theory of "[[cultural hegemony]]" to explain why people in the [[working-class]] can have a false conception of their own interests. | The ideologies of the dominant class of a society ("dominant ideology") are proposed to all members of that society in order to make the ruling class' interests appear to be the interests of all. Ruled class are "educated" to share and believe "dominant ideology" as if it is good for all or universally valid claims. [[György Lukács]] (1885 – 1971) described this as a projection of the [[class consciousness]] of the ruling class, while [[Antonio Gramsci]] (1891 – 1937) advanced the theory of "[[cultural hegemony]]" to explain why people in the [[working-class]] can have a false conception of their own interests. | ||

| − | [[Karl Mannheim]] (1893 – 1947), a German sociologist, broadened the concept of ideology in his ''Ideologie und Utopie'' (1929). | + | [[Karl Mannheim]] (1893 – 1947), a German [[sociology|sociologist]], broadened the concept of ideology in his ''Ideologie und Utopie'' (1929; ''Ideology and Utopia''). Mannheim attempted to move beyond what he saw as the 'total' but 'special' Marxist conception of ideology to a 'general' and 'total' conception which acknowledged that all ideologies resulted from social life including Marxism. |

| + | He established a [[sociology of knowledge]] as the study of the relationship between human thought and the social context within which it arises, and of the effects prevailing ideas have on societies. He distinguished a "general total conception of ideology" from Marx's "special conception of ideology" and tried to build sociology of knowledge based upon the broader concept of ideology. Mannheim recognized ideological element (impacts from social realities to consciousness, ideas, and thought) in any thought including sociologists own views. But, he argued that it is possible to have general perspective by having critical reflection upon itself. While Marx's concept of ideology was narrow and lacked self-critical elements, Hannheim argued, his concept was broader and had self-critical function. | ||

| + | The list of reviewers of the German ''Ideology and Utopia'' includes a remarkable roll call of individuals who became famous in exile, after the rise of Hitler: [[Hannah Arendt]], [[Max Horkheimer]], [[Herbert Marcuse]], [[Paul Tillich]], [[Hans Speier]], [[Günther Stern]] (aka Günther Anders), Waldemar Gurian, Siegfried Kracauer, [[Otto Neurath]], Karl August Wittfogel, Béla Fogarasi, and [[Leo Strauss]]. | ||

| − | + | Mannheim's ambitious attempt to promote a comprehensive sociological analysis of the structures of knowledge was treated with suspicion by Marxists and neo-Marxists of the [[Frankfurt School]]. They saw the rising popularity of the sociology of knowledge as a neutralization and a betrayal of Marxist inspiration. | |

| − | + | Frankfurt School theorists such as Horkheimer, [[Adorno]], and [[Erich Fromm]], who exiled to the United States from [[Nazis]], carried out the analysis of ideology from the perspective of [[social psychology]] by incorporating [[Freudian psychoanalysis]] and American empirical research methods. They applied their critique of ideology to the analysis of "totalitarian personality" | |

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | [[Daniel Bell]], and [[Jürgen Habermas]], amongst many others. | ||

== Analysis of ideology == | == Analysis of ideology == | ||

Revision as of 22:49, 8 November 2007

| The Politics series: |

|---|

|

| Subseries of Politics |

|

| Politics Portal |

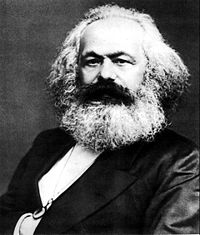

An ideology is a set of ideas, beliefs, stance, that determines a perspective to interpret social and political realities. The term is used either pejorative or neutral sense, but it contains political connotations. The word ideology was coined by Count Antoine Destutt de Tracy, a French materialist in the late 18th century, to define a "science of ideas." The current usage of the term was, however, originated from Karl Marx. Marx defined "ideology" as a "false consciousness" of a ruling class in a society, who falsely presents their ideas as if they were universal truth. Their ideas were neither universal nor objective, Marx argued, but they emerged out of and serve for their class interests. The consciousness of the ruling class, loaded with class interests but concealed, was criticized by Marx as "ideology."

Today, ideology is used in much broader sense than Marx's original formulation. In a pejorative sense, it means a set of ideas used as a political tool to achieve hidden goals and interests by distorting social, political realities. Hidden interests meant class interests for Marx, but those interests can be any other kinds of interests. This sense is closer to but broader than Marx's original formulation. In a neutral sense, it means a set of ideas accompanied with political goals, intents, interests, and commitments. While world-view does not connote a political sense, ideology always contains political implications. The main purpose behind an ideology is to offer change in society through a normative thought process. Ideologies seek application to public matters and thus make this concept central to politics. Implicitly every political tendency entails an ideology whether or not it is propounded as an explicit system of thought.

In the twentieth century, such theorists as Louis Althusser, Karl Mannheim, Adorno, Horkheimer, Erich Fromm, and others contributed to the analysis of this concept. Around 1950s and 60s, Daniel Bell, American sociologist, claimed the "end of ideology" and the coming of the era of scientific positivism. Frankfurt School theorists criticized Bell for his "scientism" as an ideology.

Historical background

The term "ideology" is a coinage by Destutt de Tracy (1754 - 1836). Tracy, a French Enlightenment thinker, attempted to establish a perspective to see ideas not from theological and metaphysical background but from sense experience and perceptions. He tried to establish a "science of ideas" and called it "ideology." Those Enlightenment thinkers who shared Tracy's idea were called "ideologistes."

Napoleon accused those Enlightenment thinkers, who attempted to promote human rights, freedom, and other ideals of the Enlightenment. He called them "ideologues" in pejorative sense, by which he meant "unrealistic idealistic fanatics." It was, however, Karl Marx who gave a new meaning to ideology, which became the origin of various contemporary meanings of this term.

Karl Marx's formulation of Ideology

In German Ideology, Marx criticized Hegelians such as Bruno Bauer and Feuerbach, who failed to capture social realities, at least from Marx's perspective. Marx accused their idealistic "false consciousness" as "ideology."

Marx further specified the concept of ideology within the contexts of his social, economic, political theory. He used ideology in a negative sense. To maintain and justify the domination, ruling class present their ideas as if they were interests-free universal truth. Under this clam, their class interests are hidden and concealed. Ruling class materialize and institutionalize their ideas as social systems. This mental attitude, consciousness, a set of ideas, which ruling class held consciously or unconsciously, was called "ideology" by Marx. He tried to expose the hidden mechanism of domination and called his critical exposure "critique of ideology."

Marx used "ideology" in two senses. In a broad sense, it meant the entire "superstructure" such as ideas, beliefs, institutions, laws, and social systems, built upon the economic "base." In a narrow sense, he meant legal, social, political, religious, philosophical, and cultural ideas and thoughts.

Marx explained the origin of ideology based upon his idea of "base/superstructure" model of society. The base refers to the means of production of society. The superstructure is formed on top of the base, and comprises that society's ideology, as well as its legal system, political system, and religions. For Marx, the base determines the superstructure: "It is men, who in developing their material inter-course, change, along with this their real existence, their thinking and the products of their thinking. Life is not determined by consciousness, but consciousness by life" (Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe 1/5). Because the ruling class controls the society's means of production, the superstructure of society, including its ideology, will be determined according to what is in the ruling class's best interests.

From Marx's perspective, economic structure determines all forms of consciousness including philosophy, religion, politics, and culture. Accordingly, all cultural products serve as ideology. The critique of ideology, therefore, entailed the critique of economic system, specifically capitalist economy. Marx's critique of ideology is, thus, carried out as the critique of economics.

Criticisms were raised for Marx's analysis of ideology. First, if all ideas are ideological, Marxism itself must be a form of ideology. Second, economic determinism is simplistic. Human beings can be motivated by other interests than economic "class interests" and there are diverse social, ethnic, religious groups who value diverse interests. Third, Marx's attempt to change society by his thought is an attempt to change the "base" by "superstructure" (ideas, thoughts), and it is a refutation to the thesis that economic base determines the superstructure.

Those criticisms to classical Marxism opened wider range of analysis on the concept of ideology.

Critique of Ideology after Marx

The ideologies of the dominant class of a society ("dominant ideology") are proposed to all members of that society in order to make the ruling class' interests appear to be the interests of all. Ruled class are "educated" to share and believe "dominant ideology" as if it is good for all or universally valid claims. György Lukács (1885 – 1971) described this as a projection of the class consciousness of the ruling class, while Antonio Gramsci (1891 – 1937) advanced the theory of "cultural hegemony" to explain why people in the working-class can have a false conception of their own interests.

Karl Mannheim (1893 – 1947), a German sociologist, broadened the concept of ideology in his Ideologie und Utopie (1929; Ideology and Utopia). Mannheim attempted to move beyond what he saw as the 'total' but 'special' Marxist conception of ideology to a 'general' and 'total' conception which acknowledged that all ideologies resulted from social life including Marxism.

He established a sociology of knowledge as the study of the relationship between human thought and the social context within which it arises, and of the effects prevailing ideas have on societies. He distinguished a "general total conception of ideology" from Marx's "special conception of ideology" and tried to build sociology of knowledge based upon the broader concept of ideology. Mannheim recognized ideological element (impacts from social realities to consciousness, ideas, and thought) in any thought including sociologists own views. But, he argued that it is possible to have general perspective by having critical reflection upon itself. While Marx's concept of ideology was narrow and lacked self-critical elements, Hannheim argued, his concept was broader and had self-critical function.

The list of reviewers of the German Ideology and Utopia includes a remarkable roll call of individuals who became famous in exile, after the rise of Hitler: Hannah Arendt, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, Paul Tillich, Hans Speier, Günther Stern (aka Günther Anders), Waldemar Gurian, Siegfried Kracauer, Otto Neurath, Karl August Wittfogel, Béla Fogarasi, and Leo Strauss.

Mannheim's ambitious attempt to promote a comprehensive sociological analysis of the structures of knowledge was treated with suspicion by Marxists and neo-Marxists of the Frankfurt School. They saw the rising popularity of the sociology of knowledge as a neutralization and a betrayal of Marxist inspiration.

Frankfurt School theorists such as Horkheimer, Adorno, and Erich Fromm, who exiled to the United States from Nazis, carried out the analysis of ideology from the perspective of social psychology by incorporating Freudian psychoanalysis and American empirical research methods. They applied their critique of ideology to the analysis of "totalitarian personality"

Daniel Bell, and Jürgen Habermas, amongst many others.

Analysis of ideology

Meta-ideology is the study of the structure, form, and manifestation of ideologies. Meta-ideology posits that ideology is a coherent system of ideas, relying upon a few basic assumptions about reality that may or may not have any factual basis, but are subjective choices that serve as the seed around which further thought grows. According to this perspective, ideologies are neither right nor wrong, but only a relativistic intellectual strategy for categorizing the world. The pluses and minuses of ideology range from the vigor and fervor of true believers to ideological infallibility. Excessive need for certitude lurks at fundamentalist levels in politics, religions, and elsewhere. It is not only the Catholic pope or other believers who consider themselves in some ways infallible.

The works of George Walford and Harold Walsby, done under the heading of systematic ideology, are attempts to explore the relationships between ideology and social systems.

David W. Minar describes six different ways in which the word "ideology" has been used:

- As a collection of certain ideas with certain kinds of content, usually normative;

- As the form or internal logical structure that ideas have within a set;

- By the role in which ideas play in human-social interaction;

- By the role that ideas play in the structure of an organization;

- As meaning, whose purpose is persuasion; and

- As the locus of social interaction, possibly.

For Willard A. Mullins, an ideology is composed of four basic characteristics:

- it must have power over cognitions;

- it must be capable of guiding one's evaluations;

- it must provide guidance towards action;

- and, as stated above, must be logically coherent.

Mullins emphasizes that an ideology should be contrasted with the related (but different) issues of utopia and historical myth.

The German philosopher Christian Duncker called for a "critical reflection of the ideology concept" (2006). In his work, he strove to bring the concept of ideology into the foreground, as well as the closely connected concerns of epistemology and history. In this work, the term ideology is defined in terms of a system of presentations that explicitly or implicitly claim to absolute truth.

Though the word "ideology" is most often found in political discourse, there are many different kinds of ideology: political, social, epistemological, ethical, and so on.

Louis Althusser's Ideological State Apparatuses

Louis Althusser proposed a materialistic conception of ideology, which made use of a special type of discourse: the lacunar discourse. A number of propositions, which are never untrue, suggest a number of other propositions, which are. In this way, the essence of the lacunar discourse is what is not told (but is suggested).

For example, the statement 'All are equal before the law', which is a theoretical groundwork of current legal systems, suggests that all people may be of equal worth or have equal 'opportunities'. This is not true, for the concept of private property over the means of production results in some people being able to own more (much more) than others, and their property brings power and influence (the rich can afford better lawyers, among other things, and this puts in question the principle of equality before the law).

Althusser also invented the concept of Ideological State Apparatuses to explain his theory of ideology. His first thesis was that "Ideology has no history": since the epistemological break is a continuous process (and not a determined event), science and philosophy must always struggle against ideology, which is, according to Marx, defined as the reproduction of the possibilities of production. His second thesis, "Ideas are material," explains his materialistic attitude, which he illustrated with the "scandalous advice" of Pascal toward unbelievers: "kneel and pray, and then you will believe," thus reversing the primacy of idealism toward materialism. However, this mustn't be misunderstood as simple behaviorism, as there may be, as Pierre Macherey put it, a "subjectivity without subject"; in other words, a form of non-personal liberty, as in Deleuze's conception of becoming-other.

Feminism as critique of ideology

Naturalizing socially constructed patterns of behavior has always been an important mechanism in the production and reproduction of ideologies. Feminist theorists have paid close attention to these mechanisms. Adrienne Rich e.g. has shown how to understand motherhood as a social institution. However, 'feminism' is not a homogenous whole, and some corners of feminist thought criticise the critique of social constructionism, by advocating that it disregards too much of human nature and natural tendencies. The debate, they say, is about the normative/naturalistic fallacy - the idea that just something 'being' natural does not necessarily mean it 'ought' to be the case.

Political ideologies

This is a list of the ideologies of parties. Many political parties base their political action and programme on an ideology. In social studies, a political ideology is a certain ethical set of ideals, principles, doctrines, myths or symbols of a social movement, institution, class, or large group that explains how society should work, and offers some political and cultural blueprint for a certain social order. A political ideology largely concerns itself with how to allocate power and to what ends it should be used. Some parties follow a certain ideology very closely, while others may take broad inspiration from a group of related ideologies without specifically embracing any one of them.

Political ideologies have two dimensions:

- Goals: How society should work (or be arranged).

- Methods: The most appropriate ways to achieve the ideal arrangement.

An ideology is a collection of ideas. Typically, each ideology contains certain ideas on what it considers to be the best form of government (e.g. democracy, theocracy, etc), and the best economic system (e.g. capitalism, socialism, etc). Sometimes the same word is used to identify both an ideology and one of its main ideas. For instance, "socialism" may refer to an economic system, or it may refer to an ideology which supports that economic system.

Ideologies also identify themselves by their position on the political spectrum (such as the left, the center or the right), though this is very often controversial. Finally, ideologies can be distinguished from political strategies (e.g. populism) and from single issues that a party may be built around (e.g. opposition to European integration or the legalisation of marijuana).

Studies of the concept of ideology itself (rather than specific ideologies) have been carried out under the name of systematic ideology.

Political ideologies are concerned with many different aspects of a society, some of which are: the economy, education, health care, labor law, criminal law, the justice system, the provision of social security and social welfare, trade, the environment, minors, immigration, race, use of the military, patriotism and established religion.

There are many proposed methods for the classification of political ideologies. See the political spectrum article for a more in-depth discussion of these different methods (each of whom generates a specific political spectrum).

Epistemological ideologies

Even when the challenging of existing beliefs is encouraged, as in science, the dominant paradigm or mindset can prevent certain challenges, theories or experiments from being advanced.

There are critics who view science as an ideology in itself, or being an effective ideology, called scientism. Some scientists respond that, while the scientific method is itself an ideology, as it is a collection of ideas, there is nothing particularly wrong or bad about it.

Other critics point out that while science itself is not a misleading ideology, there are some fields of study within science that are misleading. Two examples discussed here are in the fields of ecology and economics.

A special case of science adopted as ideology is that of ecology, which studies the relationships between living things on Earth. Perceptual psychologist J. J. Gibson believed that human perception of ecological relationships was the basis of self-awareness and cognition itself. Linguist George Lakoff has proposed a cognitive science of mathematics wherein even the most fundamental ideas of arithmetic would be seen as consequences or products of human perception - which is itself necessarily evolved within an ecology.

Deep ecology and the modern ecology movement (and, to a lesser degree, Green parties) appear to have adopted ecological sciences as a positive ideology.

Some accuse ecological economics of likewise turning scientific theory into political economy, although theses in that science can often be tested. The modern practice of green economics fuses both approaches and seems to be part science, part ideology.

This is far from the only theory of economics to be raised to ideology status - some notable economically-based ideologies include mercantilism, social Darwinism, communism, laissez-faire economics, and free trade. There are also current theories of safe trade and fair trade which can be seen as ideologies.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Mullins, Willard A. (1972) "On the Concept of Ideology in Political Science." The American Political Science Review. American Political Science Association.

- Minar, David M. (1961) "Ideology and Political Behavior," Midwest Journal of Political Science. Midwest Political Science Association.

- Pinker, Steven. (2002) "The Blank Slate: The Modern Denial of Human Nature." New York: Penguin Group, Inc. ISBN 0-670-03151-8

- Christian Duncker: Kritische Reflexionen des Ideologiebegriffes, 2006, ISBN 1-903343-88-7

Further reading

- Hawkes, David (2003) Ideology (2nd ed.), Routledge, ISBN 0-415-29012-0

- Minogue, Kenneth (1985) Alien Powers: The Pure Theory of Ideology, Palgrave Macmillan, ISBN 0-312-01860-6

- Eagleton, Terry (1991) Ideology. An introduction, Verso, ISBN 0-86091-319-8

See also

- Hegemony

- Posthegemony

- -ism

- List of ideologies named after people

- Paradigm

- System justification

- Social criticism

- Socially constructed reality

External links

- Ideology Study Guide

- Ideology Research

- Louis Althusser's "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses"

| |||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.