Difference between revisions of "Humanism" - New World Encyclopedia

| (52 intermediate revisions by 11 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{2Copyedited}} | |

| − | |||

| − | {{ | ||

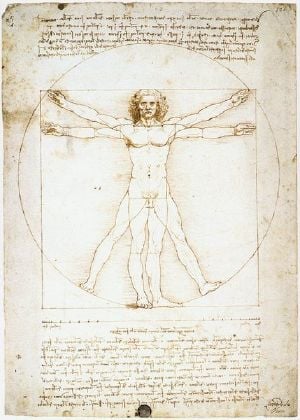

| − | + | [[Image:Vitruvian.jpg|thumb|300px|The ''Vitruvian Man'', [[Leonardo da Vinci]]'s study of the ideal proportions of the [[human body]]]] | |

| − | '''Humanism''' | + | '''Humanism''' is an attitude of thought which gives primary importance to [[human being]]s. Its outstanding historical example was [[Renaissance]] humanism from the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, which developed from the rediscovery by [[Europe]]an scholars of classical [[Latin (language)|Latin]] and [[Ancient Greek|Greek]] texts. As a reaction against the religious authoritarianism of Medieval [[Catholicism]], it emphasized human dignity, [[beauty]], and potential, and affected every aspect of [[culture]] in Europe, including [[philosophy]], [[music]], and the arts. This humanist emphasis on the value and importance of the individual influenced the [[Protestant Reformation]], and brought about social and [[politics|political]] change in Europe. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | There was another round of revival of humanism in the [[Age of Enlightenment]] in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as a reaction against the newly prevalent dogmatic authoritarianism of [[Lutheranism]], [[Calvinism]], [[Anglicanism]], and the [[Counter-Reformation]] from around the end of the sixteenth century to the seventeenth century. During the last two centuries, various elements of Enlightenment humanism have been manifested in philosophical trends such as [[existentialism]], [[utilitarianism]], [[pragmatism]], and [[Marxism]]. Generally speaking, Enlightenment humanism was more advanced than Renaissance humanism in its secular orientation, and produced [[atheism]], Marxism, as well as [[Secular Humanism|secular humanism]]. Secular humanism, which denies God and attributes the universe entirely to material forces, today has replaced religion for many people. | |

| − | + | {{toc}} | |

| − | + | Humanism is an inevitable reaction to [[theism]] when it is authoritarian and dogmatic. For a complete understanding of the nature and purpose of human life, humanism and theism are complementary. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Humanism in Renaissance and Enlightenment== | |

| + | ===Renaissance humanism=== | ||

| + | [[Renaissance]] humanism was a [[Europe]]an intellectual and [[culture|cultural]] movement which began in Florence, [[Italy]], in the last decades of the fourteenth century, rose to prominence in the fifteenth century, and spread throughout the rest of Europe in the sixteenth century. The term "humanism" itself was coined much later, in 1808, by German educator F.J. Niethammer to describe a program of study distinct from science and engineering; but in the fifteenth century, the term ''"umanista,"'' or ''"humanist,"'' was current, meaning a student of human affairs or human nature. The movement developed from the rediscovery by European scholars of many [[Ancient Greek|Greek]] and Roman texts. Its focus was on human dignity and potential and the place of mankind in nature; it valued [[reason]] and the evidence of the senses in understanding [[truth]]. The humanist emphasis upon [[art]] and the senses marked a great change from the contemplation on the [[Bible|biblical]] values of humility, introspection, and meekness that had dominated European thought in the previous centuries. [[Beauty]] was held to represent a deep inner virtue and value, and an essential element in the path towards God. | ||

| − | [[Renaissance | + | Renaissance humanism was a reaction to Catholic [[scholasticism]] which had dominated the universities of Italy, and later [[Oxford University|Oxford]] and [[University of Paris|Paris]], and whose methodology was derived from [[Thomas Aquinas]]. Renaissance humanists followed a cycle of studies, the ''studia humanitatis'' (studies of humanity), consisting of [[grammar]], [[rhetoric]], [[poetry]], [[history]], and [[morality|moral]] [[philosophy]], based on classical Roman and Greek texts. Many humanists held positions as teachers of literature and grammar or as government bureaucrats. Humanism affected every aspect of culture in Europe, including [[music]] and the arts. It profoundly influenced philosophy by emphasizing rhetoric and a more literary presentation and by introducing Latin translations of Greek classical texts which revived many of the concepts of ancient Greek philosophy. |

| − | + | The humanist emphasis on the value and importance of the individual was not necessarily a total rejection of religion. According to historians such as Nicholas Terpstra, the Renaissance was very much characterized with activities of lay religious co-fraternities with a more internalized kind of religiosity, and it influenced the [[Protestant Reformation]], which rejected the hierarchy of the [[Roman Catholicism|Roman Catholic Church]] and declared that every individual could stand directly before [[God]].<ref>Nicholas Terpstra, ''Lay Confraternities and Civic Religion in Renaissance Bologna'' (Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0521522618).</ref> Humanist values also brought about social and political change by acknowledging the value and dignity of every individual regardless of social and economic status. Renaissance humanism also inspired the study of biblical sources and newer, more accurate translations of biblical texts. | |

| − | According to | ||

| − | + | Humanist scholars from this period include the Dutch theologian [[Desiderius Erasmus|Erasmus]], the English author [[Thomas More]], the French writer [[Francois Rabelais]], the Italian poet [[Francesco Petrarch]], and the Italian scholar [[Giovanni Pico della Mirandola]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | === | + | ===Enlightenment humanism=== |

| − | + | The term, "Enlightenment humanism," is not as well known as "Renaissance humanism." The reason is that the relationship of humanism to the [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment]] has not been as much clarified by [[history|historians]] than that between humanism and the Renaissance. But, there actually existed humanism in the Enlightenment as well, and quite a few historians have related humanism to the Enlightenment.<ref>Aram Vartanian, ''Science and Humanism in the French Enlightenment'' (Charlottesville, VA: Rookwood Press, 1999, ISBN 978-1886365117).</ref> Enlightenment humanism is characterized by such key words as [[autonomy]], [[reason]], and progress, and it is usually distinguished from Renaissance humanism because of its more secular nature. While Renaissance humanism was still somewhat religious, developing an internalized type of religiosity, which influenced the Protestant Reformation, Enlightenment humanism marked a radical departure from religion. | |

| − | + | The Enlightenment was a reaction against the religious dogmatism of the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The religious dogmatism of that time in Europe had been developed in three domains: 1) Protestant scholasticism by [[Lutheranism|Lutheran]] and [[Calvinism|Calvinist]] divines, 2) "Jesuit scholasticism" (sometimes called the "second scholasticism") by the [[Counter-Reformation]], and 3) the theory of the divine right of kings in the [[Church of England]]. It had fueled the bloody [[Thirty Years' War]] (1618-1648) and the English Civil War (1642-1651). The Enlightenment rejected this religious dogmatism. The intellectual leaders of the Enlightenment regarded themselves as a courageous elite who would lead the world into progress from a long period of doubtful tradition and ecclesiastical tyranny. They reduced religion to those essentials which could only be "rationally" defended, i.e., certain basic moral principles and a few universally held beliefs about God. Taken to one logical extreme, the Enlightenment even resulted in [[atheism]]. Aside from these universal principles and beliefs, religions in their particularity were largely banished from the public square. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Humanism after the Enlightenment== | |

| − | + | After the [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment]], its humanism continued and was developed in the next two centuries. Humanism has come to encompass a series of interrelated concepts about the nature, definition, capabilities, and values of human persons. In it refers to perspectives in [[philosophy]], [[anthropology]], [[history]], [[epistemology]], [[aesthetics]], [[ontology]], [[ethics]], and [[politics]], which are based on the [[human being]] as a point of reference. Humanism refers to any perspective which is committed to the centrality and interests of human beings. It also refers to a belief that [[reason]] and [[autonomy]] are the basic aspects of human existence, and that the foundation for ethics and society is autonomy and [[morality|moral]] equality. During the last two centuries, various elements of humanism have been manifested in philosophical views including [[existentialism]], [[utilitarianism]], [[pragmatism]], [[personalism]], and [[Marxism]]. | |

| − | + | Also in the area of [[education]], the late nineteenth century educational humanist William T. Harris, who was U.S. Commissioner of Education and founder of the ''Journal of Speculative Philosophy,'' followed the Enlightenment theory of education that the studies that develop human intellect are those that make humans "most truly human." His "Five Windows of the Soul" ([[mathematics]], [[geography]], history, [[grammar]], and [[literature]]/[[art]]) were believed especially appropriate for the development of the distinct intellectual faculties such as the analytical, the mathematical, and the linguistic. Harris, an egalitarian who worked to bring education to all children regardless of [[gender]] or [[economics|economic]] status, believed that education in these subjects provided a "civilizing insight" that was necessary in order for [[democracy]] to flourish. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | == Modern humanist movements == | |

| − | + | One of the earliest forerunners of contemporary chartered humanist organizations was the Humanistic Religious Association formed in 1853 in [[London]]. This early group was [[democracy|democratically]] organized, with male and female members participating in the election of the leadership and promoted [[knowledge]] of the [[science]]s, [[philosophy]], and the arts. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Active in the early 1920s, Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller considered his work to be tied to the humanist movement. Schiller himself was influenced by the pragmatism of [[William James]]. In 1929, [[Charles Francis Potter]] founded the First Humanist Society of New York whose advisory board included [[Julian Huxley]], [[John Dewey]], [[Albert Einstein]], and [[Thomas Mann]]. Potter was a minister from the Unitarian tradition and in 1930, he and his wife, Clara Cook Potter, published ''Humanism: A New Religion.'' Throughout the 1930s, Potter was a well-known advocate of women’s rights, access to birth control, civil divorce laws, and an end to capital punishment. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Raymond B. Bragg, the associate editor of ''The New Humanist,'' sought to consolidate the input of L. M. Birkhead, Charles Francis Potter, and several members of the Western Unitarian Conference. Bragg asked Roy Wood Sellars to draft a document based on this information which resulted in the publication of the ''Humanist Manifesto'' in 1933. It referred to humanism as a religion, but denied all supernaturalism and went so far as to affirm that: "Religious humanists regard the universe as self-existing and not created."<ref>[https://americanhumanist.org/what-is-humanism/manifesto1/ Humanist Manifesto I] ''American Humanist Association''. Retrieved August 19, 2023.</ref> So, it was hardly religious humansim; it was rather [[Secular Humanism|secular humanism]]. The ''Manifesto'' and Potter's book became the cornerstones of modern organizations of secular humanism. They defined religion in secular terms and refused traditional [[Theism|theistic]] perspectives such as the existence of [[God]] and his act of [[Creationism|creation]]. | |

| − | + | In 1941, the American Humanist Association was organized. Noted members of The AHA include [[Isaac Asimov]], who was the president before his death, and writer [[Kurt Vonnegut]], who also was president before his death. | |

| − | + | == Secular and religious humanism == | |

| + | [[Secular Humanism|Secular humanism]] rejects [[theism|theistic]] [[religion|religious]] belief, and the existence of [[God]] or other supernatural being, on the grounds that supernatural beliefs cannot be supported rationally. Secular humanists generally believe that successful ethical, political, and social organization can be accomplished through the use of reason or other faculties of man. Many theorists of modern humanist organizations such as American Humanist Association hold this perspective. | ||

| − | + | Religious humanism embraces some form of theism, [[deism]], or supernaturalism, without necessarily being allied with organized religion. The existence of God or the divine, and the relationship between God and human beings is seen as an essential aspect of human character, and each individual is endowed with unique value through this relationship. Humanism within organized religion can refer to the appreciation of human qualities as an expression of God, or to a movement to acknowledge common humanity and to serve the needs of the human community. Religious thinkers such as [[Erasmus]], [[Blaise Pascal]], and [[Jacques Maritain]] hold this orientation. | |

| − | == | + | ==Assessment== |

| − | + | As long as [[human being]]s were created in the image of [[God]], their values and dignity are to be respected. But [[history]] shows that they were very often neglected even in the name of God or in the name of an established [[religion|religious]] institution like church. So, it was natural that [[Renaissance]] humanism occurred in the fourteenth century as a reaction against the religious authoritarianism of Medieval [[Catholicism]]. If the Renaissance was a humanist reaction, there was also a [[faith]]-oriented reaction, which was the [[Protestant Reformation]]. Hence, Medieval Catholicism is said to have been disintegrated into two very different kinds of reactions: Renaissance and Reformation. In the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there was again religious authoritarianism, which arose from among [[Lutheranism]], [[Calvinism]], [[Anglicanism]], and the [[Counter-Reformation]]. Therefore, [[Age of Enlightenment|Enlightenment]] humanism naturally emerged as a movement against it, and its more faith-oriented counterpart was [[Pietism]]. Enlightenment humanism was more advanced in its secular orientation than Renaissance humanism, and its tradition even issued in [[atheism]] and [[Marxism]]. Today, so-called [[Secular Humanism|secular humanism]] constitutes a great challenge to established religion. | |

| − | + | Humanism is an inevitable reaction to [[theism]] when it is authoritarian and dogmatic. For a complete understanding of the nature and purpose of human life, humanism and theism are complementary. As the American theologian [[Reinhold Niebuhr]] said, a "new synthesis" of Renaissance and Reformation is called for.<ref>Reinhold Niebuhr, ''The Nature and Destiny of Man: Volume II Human Destiny'' (Prentice Hall, 1980, ISBN 978-0684718590).</ref> | |

| − | + | ==Notes== | |

| − | + | <references/> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== References == | == References == | ||

| − | + | *Ehrenfeld, David W. ''The Arrogance of Humanism.'' New York, Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0195028904 | |

| − | + | *Lamont, Corliss. ''The Philosophy of Humanism.'' Humanist Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0931779077 | |

| − | + | *Niebuhr, Reinhold. ''The Nature and Destiny of Man: Volume II Human Destiny''. Prentice Hall, 1980. ISBN 978-0684718590 | |

| − | *Petrosyan, M. | + | *Petrosyan, M. ''Humanism: Its Philosophical, Ethical, and Sociological Aspects.'' Progress Publishers, 1972. {{ASIN|B0006CBZ24}} |

| + | *Said, Edward W. ''Humanism and Democratic Criticism.'' Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 978-1403947109 | ||

| + | *Terpstra, Nicholas. ''Lay Confraternities and Civic Religion in Renaissance Bologna''. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0521522618 | ||

| + | *Vartanian, Aram. ''Science and Humanism in the French Enlightenment''. Rookwood Press, 1999. ISBN 978-1886365117 | ||

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved August 19, 2023. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * [https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/07538b.htm Humanism] ''Catholic Encyclopedia''. | |

| + | * [https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/humanism-civic/ Civic Humanism] ''Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. | ||

| + | * [https://www.rep.routledge.com/articles/thematic/humanism-renaissance/v-1 Humanism, Renaissance] ''Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy''. | ||

| + | * [https://www.huumanists.org/ UU Humanist Association] | ||

| + | * [https://www.transfigurism.org/ Mormon Transhumanist Association] | ||

| + | * [https://secularhumanism.org/ Free Inquiry Magazine] ''Center for Inquiry'' | ||

| + | * [https://americanhumanist.org/ American Humanist Association] | ||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Philosophy and religion]] |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | {{Credit2|Humanism|107704225|Renaissance_humanism|108790417}} | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | ||

Latest revision as of 19:10, 19 August 2023

Humanism is an attitude of thought which gives primary importance to human beings. Its outstanding historical example was Renaissance humanism from the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, which developed from the rediscovery by European scholars of classical Latin and Greek texts. As a reaction against the religious authoritarianism of Medieval Catholicism, it emphasized human dignity, beauty, and potential, and affected every aspect of culture in Europe, including philosophy, music, and the arts. This humanist emphasis on the value and importance of the individual influenced the Protestant Reformation, and brought about social and political change in Europe.

There was another round of revival of humanism in the Age of Enlightenment in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries as a reaction against the newly prevalent dogmatic authoritarianism of Lutheranism, Calvinism, Anglicanism, and the Counter-Reformation from around the end of the sixteenth century to the seventeenth century. During the last two centuries, various elements of Enlightenment humanism have been manifested in philosophical trends such as existentialism, utilitarianism, pragmatism, and Marxism. Generally speaking, Enlightenment humanism was more advanced than Renaissance humanism in its secular orientation, and produced atheism, Marxism, as well as secular humanism. Secular humanism, which denies God and attributes the universe entirely to material forces, today has replaced religion for many people.

Humanism is an inevitable reaction to theism when it is authoritarian and dogmatic. For a complete understanding of the nature and purpose of human life, humanism and theism are complementary.

Humanism in Renaissance and Enlightenment

Renaissance humanism

Renaissance humanism was a European intellectual and cultural movement which began in Florence, Italy, in the last decades of the fourteenth century, rose to prominence in the fifteenth century, and spread throughout the rest of Europe in the sixteenth century. The term "humanism" itself was coined much later, in 1808, by German educator F.J. Niethammer to describe a program of study distinct from science and engineering; but in the fifteenth century, the term "umanista," or "humanist," was current, meaning a student of human affairs or human nature. The movement developed from the rediscovery by European scholars of many Greek and Roman texts. Its focus was on human dignity and potential and the place of mankind in nature; it valued reason and the evidence of the senses in understanding truth. The humanist emphasis upon art and the senses marked a great change from the contemplation on the biblical values of humility, introspection, and meekness that had dominated European thought in the previous centuries. Beauty was held to represent a deep inner virtue and value, and an essential element in the path towards God.

Renaissance humanism was a reaction to Catholic scholasticism which had dominated the universities of Italy, and later Oxford and Paris, and whose methodology was derived from Thomas Aquinas. Renaissance humanists followed a cycle of studies, the studia humanitatis (studies of humanity), consisting of grammar, rhetoric, poetry, history, and moral philosophy, based on classical Roman and Greek texts. Many humanists held positions as teachers of literature and grammar or as government bureaucrats. Humanism affected every aspect of culture in Europe, including music and the arts. It profoundly influenced philosophy by emphasizing rhetoric and a more literary presentation and by introducing Latin translations of Greek classical texts which revived many of the concepts of ancient Greek philosophy.

The humanist emphasis on the value and importance of the individual was not necessarily a total rejection of religion. According to historians such as Nicholas Terpstra, the Renaissance was very much characterized with activities of lay religious co-fraternities with a more internalized kind of religiosity, and it influenced the Protestant Reformation, which rejected the hierarchy of the Roman Catholic Church and declared that every individual could stand directly before God.[1] Humanist values also brought about social and political change by acknowledging the value and dignity of every individual regardless of social and economic status. Renaissance humanism also inspired the study of biblical sources and newer, more accurate translations of biblical texts.

Humanist scholars from this period include the Dutch theologian Erasmus, the English author Thomas More, the French writer Francois Rabelais, the Italian poet Francesco Petrarch, and the Italian scholar Giovanni Pico della Mirandola.

Enlightenment humanism

The term, "Enlightenment humanism," is not as well known as "Renaissance humanism." The reason is that the relationship of humanism to the Enlightenment has not been as much clarified by historians than that between humanism and the Renaissance. But, there actually existed humanism in the Enlightenment as well, and quite a few historians have related humanism to the Enlightenment.[2] Enlightenment humanism is characterized by such key words as autonomy, reason, and progress, and it is usually distinguished from Renaissance humanism because of its more secular nature. While Renaissance humanism was still somewhat religious, developing an internalized type of religiosity, which influenced the Protestant Reformation, Enlightenment humanism marked a radical departure from religion.

The Enlightenment was a reaction against the religious dogmatism of the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. The religious dogmatism of that time in Europe had been developed in three domains: 1) Protestant scholasticism by Lutheran and Calvinist divines, 2) "Jesuit scholasticism" (sometimes called the "second scholasticism") by the Counter-Reformation, and 3) the theory of the divine right of kings in the Church of England. It had fueled the bloody Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) and the English Civil War (1642-1651). The Enlightenment rejected this religious dogmatism. The intellectual leaders of the Enlightenment regarded themselves as a courageous elite who would lead the world into progress from a long period of doubtful tradition and ecclesiastical tyranny. They reduced religion to those essentials which could only be "rationally" defended, i.e., certain basic moral principles and a few universally held beliefs about God. Taken to one logical extreme, the Enlightenment even resulted in atheism. Aside from these universal principles and beliefs, religions in their particularity were largely banished from the public square.

Humanism after the Enlightenment

After the Enlightenment, its humanism continued and was developed in the next two centuries. Humanism has come to encompass a series of interrelated concepts about the nature, definition, capabilities, and values of human persons. In it refers to perspectives in philosophy, anthropology, history, epistemology, aesthetics, ontology, ethics, and politics, which are based on the human being as a point of reference. Humanism refers to any perspective which is committed to the centrality and interests of human beings. It also refers to a belief that reason and autonomy are the basic aspects of human existence, and that the foundation for ethics and society is autonomy and moral equality. During the last two centuries, various elements of humanism have been manifested in philosophical views including existentialism, utilitarianism, pragmatism, personalism, and Marxism.

Also in the area of education, the late nineteenth century educational humanist William T. Harris, who was U.S. Commissioner of Education and founder of the Journal of Speculative Philosophy, followed the Enlightenment theory of education that the studies that develop human intellect are those that make humans "most truly human." His "Five Windows of the Soul" (mathematics, geography, history, grammar, and literature/art) were believed especially appropriate for the development of the distinct intellectual faculties such as the analytical, the mathematical, and the linguistic. Harris, an egalitarian who worked to bring education to all children regardless of gender or economic status, believed that education in these subjects provided a "civilizing insight" that was necessary in order for democracy to flourish.

Modern humanist movements

One of the earliest forerunners of contemporary chartered humanist organizations was the Humanistic Religious Association formed in 1853 in London. This early group was democratically organized, with male and female members participating in the election of the leadership and promoted knowledge of the sciences, philosophy, and the arts.

Active in the early 1920s, Ferdinand Canning Scott Schiller considered his work to be tied to the humanist movement. Schiller himself was influenced by the pragmatism of William James. In 1929, Charles Francis Potter founded the First Humanist Society of New York whose advisory board included Julian Huxley, John Dewey, Albert Einstein, and Thomas Mann. Potter was a minister from the Unitarian tradition and in 1930, he and his wife, Clara Cook Potter, published Humanism: A New Religion. Throughout the 1930s, Potter was a well-known advocate of women’s rights, access to birth control, civil divorce laws, and an end to capital punishment.

Raymond B. Bragg, the associate editor of The New Humanist, sought to consolidate the input of L. M. Birkhead, Charles Francis Potter, and several members of the Western Unitarian Conference. Bragg asked Roy Wood Sellars to draft a document based on this information which resulted in the publication of the Humanist Manifesto in 1933. It referred to humanism as a religion, but denied all supernaturalism and went so far as to affirm that: "Religious humanists regard the universe as self-existing and not created."[3] So, it was hardly religious humansim; it was rather secular humanism. The Manifesto and Potter's book became the cornerstones of modern organizations of secular humanism. They defined religion in secular terms and refused traditional theistic perspectives such as the existence of God and his act of creation.

In 1941, the American Humanist Association was organized. Noted members of The AHA include Isaac Asimov, who was the president before his death, and writer Kurt Vonnegut, who also was president before his death.

Secular and religious humanism

Secular humanism rejects theistic religious belief, and the existence of God or other supernatural being, on the grounds that supernatural beliefs cannot be supported rationally. Secular humanists generally believe that successful ethical, political, and social organization can be accomplished through the use of reason or other faculties of man. Many theorists of modern humanist organizations such as American Humanist Association hold this perspective.

Religious humanism embraces some form of theism, deism, or supernaturalism, without necessarily being allied with organized religion. The existence of God or the divine, and the relationship between God and human beings is seen as an essential aspect of human character, and each individual is endowed with unique value through this relationship. Humanism within organized religion can refer to the appreciation of human qualities as an expression of God, or to a movement to acknowledge common humanity and to serve the needs of the human community. Religious thinkers such as Erasmus, Blaise Pascal, and Jacques Maritain hold this orientation.

Assessment

As long as human beings were created in the image of God, their values and dignity are to be respected. But history shows that they were very often neglected even in the name of God or in the name of an established religious institution like church. So, it was natural that Renaissance humanism occurred in the fourteenth century as a reaction against the religious authoritarianism of Medieval Catholicism. If the Renaissance was a humanist reaction, there was also a faith-oriented reaction, which was the Protestant Reformation. Hence, Medieval Catholicism is said to have been disintegrated into two very different kinds of reactions: Renaissance and Reformation. In the late sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, there was again religious authoritarianism, which arose from among Lutheranism, Calvinism, Anglicanism, and the Counter-Reformation. Therefore, Enlightenment humanism naturally emerged as a movement against it, and its more faith-oriented counterpart was Pietism. Enlightenment humanism was more advanced in its secular orientation than Renaissance humanism, and its tradition even issued in atheism and Marxism. Today, so-called secular humanism constitutes a great challenge to established religion.

Humanism is an inevitable reaction to theism when it is authoritarian and dogmatic. For a complete understanding of the nature and purpose of human life, humanism and theism are complementary. As the American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr said, a "new synthesis" of Renaissance and Reformation is called for.[4]

Notes

- ↑ Nicholas Terpstra, Lay Confraternities and Civic Religion in Renaissance Bologna (Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 978-0521522618).

- ↑ Aram Vartanian, Science and Humanism in the French Enlightenment (Charlottesville, VA: Rookwood Press, 1999, ISBN 978-1886365117).

- ↑ Humanist Manifesto I American Humanist Association. Retrieved August 19, 2023.

- ↑ Reinhold Niebuhr, The Nature and Destiny of Man: Volume II Human Destiny (Prentice Hall, 1980, ISBN 978-0684718590).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ehrenfeld, David W. The Arrogance of Humanism. New York, Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0195028904

- Lamont, Corliss. The Philosophy of Humanism. Humanist Press, 1997. ISBN 978-0931779077

- Niebuhr, Reinhold. The Nature and Destiny of Man: Volume II Human Destiny. Prentice Hall, 1980. ISBN 978-0684718590

- Petrosyan, M. Humanism: Its Philosophical, Ethical, and Sociological Aspects. Progress Publishers, 1972. ASIN B0006CBZ24

- Said, Edward W. Humanism and Democratic Criticism. Palgrave Macmillan, 2004. ISBN 978-1403947109

- Terpstra, Nicholas. Lay Confraternities and Civic Religion in Renaissance Bologna. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0521522618

- Vartanian, Aram. Science and Humanism in the French Enlightenment. Rookwood Press, 1999. ISBN 978-1886365117

External links

All links retrieved August 19, 2023.

- Humanism Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Civic Humanism Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Humanism, Renaissance Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- UU Humanist Association

- Mormon Transhumanist Association

- Free Inquiry Magazine Center for Inquiry

- American Humanist Association

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.