Difference between revisions of "Hamlet" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (44 intermediate revisions by 12 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebcompleted}}{{2Copyedited}}{{Copyedited}}{{approved}}{{Images OK}}{{submitted}}{{Paid}} |

| − | [[Image: | + | [[Image:Eugène Ferdinand Victor Delacroix 018.jpg|thumb|right|300px|''Hamlet and Horatio in the cemetery'' by [[Eugène Delacroix]]]] |

| − | ''''' | + | '''''Hamlet: Prince of Denmark''''' is a [[tragedy]] by [[William Shakespeare]]. It is one of his best-known works, and also one of the most-quoted writings in the English language.<ref>''Hamlet'' has 208 quotations in the ''Oxford Dictionary of Quotations''; it takes up 10 of 85 pages dedicated to Shakespeare in the 1986 ''Bartlett's Familiar Quotations''.</ref> ''Hamlet'' has been called "the first great tragedy Europe had produced for two thousand years"<ref>Frank Kermode, "Hamlet, Prince of Denmark," from ''The Riverside Shakespeare.'' (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1974 ISBN 0-39504402-2) 1135 </ref> and it is universally included on lists of the world's greatest books.<ref>Harvard Classics, Great Books. ''Great Books of the Western World''; [[Harold Bloom]]'s ''The Western Canon''; Columbia College Core Curriculum.</ref> It is also one of the most widely performed of Shakespeare's plays; for example, it has topped the list of stagings at the [[Royal Shakespeare Company]] since 1879.<ref>David Crystal and Ben Crystal. ''The Shakespeare Miscellany'' (New York: Overlook Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1585677160), 66.</ref> With 4,042 lines and 29,551 words, ''Hamlet'' is also the longest Shakespeare play.<ref>Based on the first edition of ''The Riverside Shakespeare'' (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1974).</ref> |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | ''Hamlet'' is a tragedy of the "[[revenge]]" genre, yet transcends the form through unprecedented emphasis on the conflicted mind of the title character. In a reversal of dramatic priorities, Hamlet's inner turmoil—his duty to his slain father, his outrage with his morally compromised mother, and his distraction over the prevailing religious imperatives—provide the context for the play's external action. Hamlet's restless mind, unmoored from faith, proves to be an impediment to action, justifying [[Friedrich Nietzsche|Nietzsche]]'s judgment on Hamlet that "one who has gained knowledge . . . feel[s] it to be ridiculous or humiliating [to] be asked to set right a world that is out of joint." <ref>Friedrich Nietzsche, ''The Birth of Tragedy,'' quoted in Harold Bloom, ''Shakespeare: The Birth of the Human'' (New York: Riverhead, 1998 ISBN 1573221201) 393-394</ref> Hamlet's belated decision to act, his blundering murder of the innocent Polonius, sets in motion the inexorable tragedy of madness, murder, and dissolution of the moral order. | ||

| − | + | == Sources == | |

| + | The story of the Danish prince, "Hamlet," who plots revenge on his uncle, the current king, for killing his father, the former king, is an old one. Many of the story elements, from Hamlet's feigned madness, his mother's hasty marriage to the usurper, the testing of the prince's madness with a young woman, the prince talking to his mother and killing a hidden [[espionage|spy]], and the prince being sent to England with two retainers and substituting for the letter requesting his execution for one requesting theirs are already here in this medieval tale, recorded by [[Saxo Grammaticus]] in his ''Gesta Danorum'' around 1200. A reasonably accurate version of Saxo was rendered into French in 1570 by [[François de Belleforest]] in his ''Histoires Tragiques.''<ref>Philip Edwards. ''Hamlet, Prince of Denmark.'' (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0521532523), 1-2.</ref> | ||

| − | + | Shakespeare's main source, however, is believed to have been an earlier play—now lost (and possibly by [[Thomas Kyd]])—known as the ''Ur-Hamlet.'' This earlier Hamlet play was in performance by 1589, and seems to have introduced a ghost for the first time into the story.<ref>Harold Jenkins. ''Hamlet (Arden Shakespeare, Second Series)'' (London: The Arden Shakespeare, 1982, ISBN 1903436672), 82-85.</ref> Scholars are unable to assert with any confidence how much Shakespeare took from this play, how much from other contemporary sources (such as Kyd's ''The Spanish Tragedy''), and how much from Belleforest (possibly something) or Saxo (probably nothing). In fact, popular scholar [[Harold Bloom]] has advanced the (as yet unpopular) notion that Shakespeare himself wrote the ''Ur-Hamlet'' as a form of early draft.<ref>Bloom advances this theory in both his major popular works on Shakespeare, ''Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human.'' (New York: Riverhead Books, 1998, ISBN 1573221201) and ''Hamlet: Poem Unlimited.'' (New York: Riverhead Books, 2003, ISBN 157322233X).</ref> No matter the sources, Shakespeare's ''Hamlet'' has elements that the medieval version does not, such as the secrecy of the murder, a ghost that urges revenge, the "other sons" (Laertes and Fortinbras), the testing of the king via a play, and the mutually fatal nature of Hamlet's (nearly incidental) "revenge."<ref>Edwards, 2.</ref><ref>See Jenkins, 82-122 for a complex discussion of all sorts of possible influences that found their way into the play.</ref> | |

| − | [[ | ||

| − | The | ||

| − | + | ==Date and Texts== | |

| + | [[Image:Hamlet quarto 3rd.jpg|thumb|right|200px|The third [[quarto]] of ''Hamlet'' (1605); a straight reprint of the second quarto (1604)]] | ||

| + | ''Hamlet'' was entered into the Register of the Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers on July 26, 1602. A so-called "bad" First Quarto (referred to as "Q1") was published in 1603, by the booksellers Nicholas Ling and John Trundell. Q1 contains just over half of the text of the later Second Quarto ("Q2") published in 1604,<ref>Some copies of Q2 are dated 1605, possibly reflecting a second impression; so that Q2 is often dated "1604/5."</ref> again by Nicholas Ling. Reprints of Q2 followed in 1611 (Q3) and 1637 (Q5); there was also an undated Q4 (possibly from 1622). The First Folio text (often referred to as "F1") appeared as part of Shakespeare's collected plays published in 1623. Q1, Q2, and F1 are the three elements in the textual problem of ''Hamlet.'' | ||

| − | + | The play was revived early in the [[English Restoration|Restoration]] era; Sir [[William Davenant]] staged a 1661 production at Lincoln's Inn Fields. David Garrick mounted a version at Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1772 that omitted the gravediggers and expanded his own leading role. William Poel staged a production of the Q1 text in 1881.<ref>F. E. Halliday. ''A Shakespeare Companion, 1564-1964.'' (Baltimore: Penguin, 1969, ISBN 978-0140530117), 204.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | There are three extant texts of ''Hamlet'' from the early 1600s: the "first quarto" ''Hamlet'' of 1603 (called "Q1"), the "second quarto" ''Hamlet'' of 1604/5 ("Q2"), and the ''Hamlet'' text within the First Folio of 1623 ("F1"). Later quartos and folios are considered derivative of these, so are of little interest in capturing Shakespeare's original text. Q1 itself has been viewed with skepticism, and in practice Q2 and F1 are the editions upon which editors mostly rely. However, these two versions have some significant differences that have produced a growing body of commentary, starting with early studies by J. Dover Wilson and G. I. Duthie, and continuing into the present. | |

| − | + | Early editors of Shakespeare's works, starting with Nicholas Rowe (1709) and Lewis Theobald (1733), combined material from the two earliest known sources of ''Hamlet,'' Q2 and F1. Each text contains some material the other lacks, and there are many minor differences in wording, so that only a little more than two hundred lines are identical between them. Typically, editors have taken an approach of combining, "conflating," the texts of Q2 and F1, in an effort to create an inclusive text as close as possible to the ideal Shakespeare original. Theobald's version became standard for a long time.<ref>G. R. Hibbard, (ed.), ''Hamlet (Oxford's World's Classics).'' (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987, reprinted 1998, ISBN 0192834169), 22-23.</ref> Certainly, the "full text" philosophy that he established has influenced editors to the current day. Many modern editors have done essentially the same thing Theobald did, also using, for the most part, the 1604/5 quarto and the 1623 folio texts. | |

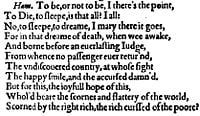

| + | [[Image:To be or not to be (Q1).jpg|thumb|right|200px|The first quarto's rendering of the "To be or not to be" [[soliloquy]]]] | ||

| + | The discovery of Q1 in 1823,<ref>Jenkins, 14.</ref> when its existence had not even been suspected earlier, caused considerable interest and excitement, while also raising questions. The deficiencies of the text were recognized immediately—Q1 was instrumental in the development of the concept of a Shakespeare "bad quarto." Yet Q1 also has its value: it contains stage directions which reveal actual stage performance in a way that Q2 and F1 do not, and it contains an entire scene (usually labeled IV, vi) that is not in either Q2 or F1. Also, Q1 is useful simply for comparison to the later publications. At least 28 different productions of the Q1 text since 1881 have shown it eminently fit for the stage. Q1 is generally thought to be a "memorial reconstruction" of the play as it may have been performed by Shakespeare's own company, although there is disagreement whether the reconstruction was [[piracy|pirated]] or authorized. It is considerably shorter than Q2 or F1, apparently because of significant cuts for stage performance. It is thought that one of the actors playing a minor role (Marcellus, certainly, perhaps Voltemand as well) in the legitimate production was the source of this version. | ||

| − | + | Another theory is that the Q1 text is an abridged version of the full length play intended especially for traveling productions (the aforementioned university productions, in particular.) Kathleen Irace espouses this theory in her New Cambridge edition, "The First Quarto of Hamlet." The idea that the Q1 text is not riddled with error, but is in fact a totally viable version of the play has led to several recent Q1 productions (perhaps most notably, Tim Sheridan and Andrew Borba's 2003 production at the Theatre of NOTE in [[Los Angeles]], for which Ms. Irace herself served as dramaturg).<ref>Ann Thompson and Neil Taylor. ''Hamlet, The Texts of 1603 and 1623 (The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series).'' (London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2006, ISBN 1904271804).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | + | As with the two texts of ''[[King Lear]],'' some contemporary scholarship is moving away from the ideal of the "full text," supposing its inapplicability to the case of ''Hamlet.'' The Arden Shakespeare's 2006 publication of different texts of ''Hamlet'' in different volumes is perhaps the best evidence of this shifting focus and emphasis.<ref>Thompson and Taylor.</ref> However, any abridgement of the standard conflation of Q2 and F1 runs the obvious risk of omitting genuine Shakespeare writing. | |

| − | + | ==Performance History== | |

| − | + | The earliest recorded performance of ''Hamlet'' was in June 1602; in 1603 the play was acted at both universities, [[University of Cambridge|Cambridge]] and [[University of Oxford|Oxford]]. Along with ''[[Richard II (play)|Richard II]],'' ''Hamlet'' was acted by the crew of Capt. William Keeling aboard the [[British East India Company]] ship ''Dragon,'' off [[Sierra Leone]], in September 1607. More conventional Court performances occurred in 1619 and in 1637, the latter on January 24 at Hampton Court Palace. Since Hamlet is second only to Falstaff among Shakespeare's characters in the number of allusions and references to him in contemporary literature, the play was certainly performed with a frequency missed by the historical record.<ref>Hibbard, 17.</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | <ref> | + | Actors who have played Hamlet include [[Laurence Olivier]], (1937) [[John Gielgud]] (1939), Mel Gibson, and Derek Jacobi (1978), who played the title role of Hamlet at Elsinore Castle in [[Denmark]], the actual setting of the play. Christopher Plummer also played the role in a [[television]] version (1966) that was filmed there. Actresses who have played the title role in ''Hamlet'' include Sarah Siddons, Sarah Bernhardt, Asta Nielsen, Judith Anderson, Diane Venora and Frances de la Tour. The youngest actor to play the role on film was Ethan Hawke, who was 29, In Hamlet (2000). The oldest is probably Johnston Forbes-Robertson, who was 60 when his performance was filmed in 1913.<ref>Martin Dworkin, "'Stay Illusion': Having Words About Shakespeare On Screen," ''Journal of Aesthetic Education'' 11 (1977): 55.</ref> Edwin Booth, the brother of [[John Wilkes Booth]]'s (the man who assassinated [[Abraham Lincoln]]), went into a brief retirement after his brother's notoriety, but made his comeback in the role of Hamlet. Rather than wait for Hamlet's first appearance in the text to meet the audience's response, Booth sat on the stage in the play's first scene and was met by a lengthy standing ovation. |

| − | + | Booth's [[Broadway]] run of ''Hamlet'' lasted for one hundred performances in 1864, an incredible run for its time. When John Barrymore played the part on Broadway to acclaim in 1922, it was assumed that he would close the production after 99 performances out of respect for Booth. But Barrymore extended the run to 101 performances so that he would have the record for himself. Currently, the longest Broadway run of ''Hamlet'' is the 1964 production starring [[Richard Burton]] and directed by John Gielgud, which ran for 137 performances. The actor who has played the part most frequently on Broadway is Maurice Evans, who played Hamlet for 267 performances in productions mounted in 1938, 1939, and 1945. The longest recorded London run is that of Henry Irving, who played the part for over two hundred consecutive nights in 1874 and revived it to acclaim with Ellen Terry as Ophelia in 1878. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | + | The only actor to win a [[Tony Award]] for playing Hamlet is Ralph Fiennes in 1995. Burton was nominated for the award in 1964, but lost to Sir [[Alec Guinness]] in ''Dylan.'' Hume Cronyn won the Tony Award for his performance as Polonius in that production. The only actor to win an [[Academy Award]] for playing Hamlet is [[Laurence Olivier]] in 1948. The only actor to win an [[Emmy Award]] nomination for playing Hamlet is Christopher Plummer in 1966. Margaret Leighton won an Emmy for playing Gertrude in the 1971 Hallmark Hall of Fame presentation. | |

| − | The | ||

| − | + | ==Characters== | |

| + | [[Image:Dante Gabriel Rossetti - Hamlet and Ophelia.JPG|thumb|right|250px|''Hamlet and Ophelia'' by [[Dante Gabriel Rossetti]]]] | ||

| − | + | Main characters include: | |

| + | *'''Hamlet''', the title character, is the son of the late king, for whom he was named. He has returned to Elsinore Castle from Wittenberg, where he was a [[university]] student. | ||

| + | *'''Claudius''' is the king of Denmark, elected to the throne after the death of his brother, King Hamlet. Claudius has married Gertrude, his brother's widow. | ||

| + | *'''Gertrude''' is the queen of Denmark, and King Hamlet's widow, now married to Claudius. | ||

| + | *'''The Ghost''' appears in the exact image of Hamlet's father, the late King Hamlet. | ||

| + | *'''Polonius''' is Claudius's chief advisor, and the father of Ophelia and Laertes (this character is called "Corambis" in the First Quarto of 1603). | ||

| + | *'''Laertes''' is the son of Polonius, and has returned to Elsinore Castle after living in [[Paris]]. | ||

| + | *'''Ophelia''' is Polonius's daughter, and Laertes's sister, who lives with her father at Elsinore Castle. | ||

| + | *'''Horatio''' is a good friend of Hamlet, from Wittenberg, who came to Elsinore Castle to attend King Hamlet's funeral. | ||

| + | *''''''Rosencrantz''' and '''Guildenstern'''''' are childhood friends and schoolmates of Hamlet, who were summoned to Elsinore by Claudius and Gertrude. | ||

| − | + | ==Synopsis== | |

| − | + | The play is set at Elsinore Castle, which is based on the real Kronborg Castle, [[Denmark]]. The time period of the play is somewhat uncertain, but can be understood as mostly [[Renaissance]], contemporary with Shakespeare's [[England]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ''Hamlet'' begins with Francisco on watch duty at Elsinore Castle, on a cold, dark night, at midnight. Barnardo approaches Francisco to relieve him on duty, but is unable to recognize his friend at first in the darkness. Barnardo stops and cries out, "Who's there?" The darkness and the mystery, of "who's there," set an ominous tone to start the play. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | That same night, Horatio and the sentinels see a ghost that looks exactly like their late king, King Hamlet. The Ghost reacts to them, but doesn't speak. The men discuss a military buildup in Denmark in response to Fortinbras recruiting an army. Although Fortinbras's army is supposedly for use against [[Poland]], they fear he may attack Denmark to get revenge for his father's death, and reclaim the land his father lost to King Hamlet. They wonder if the Ghost is an omen of disaster, and decide to tell Prince Hamlet about it. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | In the next scene, Claudius announces that the mourning period for his brother is officially over, and he also sends a diplomatic mission to [[Norway]], to try to deal with the potential threat from Fortinbras. Claudius and Hamlet have an exchange in which Hamlet says his line, "a little more than kin and less than kind." Gertrude asks Hamlet to stay at Elsinore Castle, and he agrees to do so, despite his wish to return to school in Wittenberg. Hamlet, upset over his father's death and his mother's "o'erhasty" marriage to Claudius, recites a [[soliloquy]] including "Frailty, thy name is woman." Horatio and the sentinels tell Hamlet about the Ghost, and he decides to go with them that night to see it. | |

| − | + | Laertes leaves to return to [[France]] after lecturing Ophelia against Hamlet. Polonius, suspicious of Hamlet's motives, also lectures her against him, and forbids her to have any further contact with Hamlet. | |

| − | + | That night, Hamlet, Horatio and Marcellus do see the Ghost again, and it beckons to Hamlet. Marcellus says his famous line, "Something is rotten in the state of Denmark." They try to stop Hamlet from following, but he does. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The Ghost speaks to Hamlet, calls for revenge, and reveals Claudius's murder of Hamlet's father. The Ghost also criticizes Gertrude, but says "leave her to heaven." The Ghost tells Hamlet to remember, says adieu, and disappears. Horatio and Marcellus arrive, but Hamlet refuses to tell them what the Ghost said. In an odd, much-discussed passage, Hamlet asks them to swear on his sword while the Ghost calls out "swear" from the earth beneath their feet. Hamlet says he may put on an "antic disposition." | |

| − | + | We then find Polonius sending Reynaldo to check up on what Laertes is doing in Paris. Ophelia enters, and reports that Hamlet rushed into her room with his clothing all askew, and only stared at her without speaking. Polonius decides that Hamlet is mad for Ophelia, and says he'll go to the king about it. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Claudius | + | Rosencrantz and Guildenstern arrive, and are instructed by Claudius and Gertrude to spend time with Hamlet and sound him out. Polonius announces that the ambassadors have returned from Norway with an agreement. Polonius tells Claudius that Hamlet is mad over Ophelia, and recommends an eavesdropping plan to find out more. Hamlet enters, "mistaking" Polonius for a "fishmonger." Rosencrantz and Guildenstern talk to Hamlet, who quickly discerns they're working for Claudius and Gertrude. The Players arrive, and Hamlet decides to try a play performance, to "catch the conscience of the king." |

| − | + | In the next scene, Hamlet recites his famous "To be or not to be" soliloquy. The famous “Nunnery Scene,” then occurs, in which Hamlet speaks to Ophelia while Claudius and Polonius hide and listen. Instead of expressing love for Ophelia, Hamlet rejects and berates her, tells her "get thee to a nunnery" and storms out. Claudius decides to send Hamlet to England. | |

| − | : | + | [[Image:Hamlet play scene cropped.png|thumb|right|450px|A detail of the engraving of [[Daniel Maclise]]'s 1842 painting ''The Play-scene in Hamlet'', portraying the moment when the guilt of Claudius is revealed]] |

| − | + | Next, Hamlet instructs the Players how to do the upcoming play performance, in a passage that has attracted interest because it apparently reflects Shakespeare's own views of how acting should be done. The play begins, during which Hamlet sits with Ophelia, and makes "mad" sexual jokes and remarks. Claudius asks the name of the play, and Hamlet says "The Mousetrap." Claudius walks out in the middle of the play, which Hamlet sees as proof of Claudius's guilt. Hamlet recites his dramatic "witching time of night" soliloquy. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Next comes the “Prayer Scene,” in which Hamlet finds Claudius, intending to kill him, but refrains because Claudius is praying. Hamlet then goes to talk to Gertrude, in the “Closet Scene.” There, Gertrude becomes frightened of Hamlet, and screams for help. Polonius is hiding behind an arras in the room, and when he also yells for help, Hamlet stabs and kills him. Hamlet emotionally lectures Gertrude, and the Ghost appears briefly, but only Hamlet sees it. Hamlet drags Polonius's body out of Gertrude's room, to take it elsewhere. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | When Claudius learns of the death of Polonius, he decides to send Hamlet to England immediately, accompanied by Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. They carry a secret order from Claudius to England to execute Hamlet. | |

| − | + | In a scene which appears at full length only in the Second Quarto, Hamlet sees Fortinbras arrive in Denmark with his army, speaks to a captain, then exits with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to board the [[ship]] to England. | |

| − | + | Next, Ophelia appears, and she has gone mad, apparently in grief over the death of her father. She sings odd songs about death and sex, says "good night" during the daytime, and exits. Laertes, who has returned from [[France]], storms the castle with a mob from the local town, and challenges Claudius, over the death of Polonius. Ophelia appears again, sings, and hands out flowers. Claudius tells Laertes that he can explain his innocence in Polonius's death. | |

| − | + | Sailors (pirates) deliver a letter from Hamlet to Horatio, saying that Hamlet's ship was attacked by pirates, who took him captive, but are returning him to Denmark. Horatio leaves with the pirates to go where Hamlet is. | |

| − | + | Claudius has explained to Laertes that Hamlet is responsible for Polonius's death. Claudius, to his surprise, receives a letter saying that Hamlet is back. Claudius and Laertes conspire to set up a [[fencing]] match at which Laertes can kill Hamlet in revenge for the death of Polonius. Gertrude reports that Ophelia is dead, after a fall from a tree into the brook, where she drowned. | |

| − | + | Two clowns, a sexton and a bailiff, make jokes and talk about Ophelia's death while the sexton digs her grave. They conclude she must have committed [[suicide]]. Hamlet, returning with Horatio, sees the grave being dug (without knowing who it's for), talks to the sexton, and recites his famous "alas, poor Yorick" speech. Hamlet and Horatio hide to watch as Ophelia's funeral procession enters. Laertes jumps into the grave excavation for Ophelia, and proclaims his love for her in high-flown terms. Hamlet challenges Laertes that he loved Ophelia more than "forty thousand" brothers could, and they scuffle briefly. Claudius calms Laertes, and reminds him of the rigged fencing match they've arranged to kill Hamlet. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In the final scene, Hamlet explains to Horatio that he became suspicious about the trip to England, and looked at the royal commission during the night when Rosencrantz and Guildenstern were asleep. After discovering the truth, Hamlet substituted a forgery, ordering England to kill Rosencrantz and Guildenstern instead of him. Osric then tells Hamlet of the [[fencing]] match, and despite his misgivings, Hamlet agrees to participate. | |

| − | + | At the match, Claudius and Laertes have arranged for Laertes to use a [[poison]]ed foil, and Claudius also poisons Hamlet's [[wine]], in case the poisoned foil doesn't work. The match begins, and Hamlet scores the first hit, "a very palpable hit." Gertrude sips from Hamlet's poisoned wine to salute him. Laertes wounds Hamlet with the poisoned foil, then they grapple and exchange foils, and Hamlet wounds Laertes, with the same poisoned foil. Gertrude announces that she's been poisoned by the wine, and dies. Laertes, also dying, reveals that Claudius is to blame, and asks Hamlet to exchange forgiveness with him, which Hamlet does. Laertes dies. | |

| − | [[ | ||

| + | Hamlet wounds Claudius with the poisoned foil, and also has him drink the wine he poisoned. Claudius dies. Hamlet, dying of his injury from the poisoned foil, says he supports Fortinbras as the next king, and that "the rest is silence." When Hamlet dies, Horatio says, "flights of angels sing thee to thy rest." Fortinbras enters, with ambassadors from England who announce that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead. Fortinbras takes over, says that Hamlet would have "proved most royal," and orders a salute to be fired, which concludes the play. | ||

| − | + | ==Analysis and criticism== | |

| + | ===Dramatic structure=== | ||

| + | In creating ''Hamlet,'' Shakespeare broke several rules, one of the largest being the rule of action over character. In his day, plays were usually expected to follow the advice of [[Aristotle]] in his ''[[Poetics (Aristotle)|Poetics]],'' which declared that a drama should not focus on character so much as action. The highlights of ''Hamlet,'' however, are not the action scenes, but the soliloquies, wherein Hamlet reveals his motives and thoughts to the audience. Also, unlike Shakespeare's other plays, there is no strong subplot; all plot forks are directly connected to the main vein of Hamlet struggling to gain revenge. The play is full of seeming discontinuities and irregularities of action. At one point, Hamlet is resolved to kill Claudius: in the next scene, he is suddenly tame. Scholars still debate whether these odd plot turns are mistakes or intentional additions to add to the play's theme of confusion and duality.<ref>W. Thomas MacCary. ''"Hamlet": A Guide to the Play.'' Greenwood Guides to Shakespeare ser. (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0313300828), 67-72, 84).</ref> | ||

| − | == | + | ===Language=== |

| + | Much of the play's language is in the elaborate, witty language expected of a royal court. This is in line with [[Baldassare Castiglione|Baldassare Castiglione's]] work, ''The Courtier'' (published in 1528), which outlines several courtly rules, specifically advising servants of royals to amuse their rulers with their inventive language. Osric and Polonius seem to especially respect this suggestion. Claudius' speech is full of rhetorical figures, as is Hamlet's and, at times, Ophelia's, while Horatio, the guards, and the gravediggers use simpler methods of speech. Claudius demonstrates an authoritative control over the language of a King, referring to himself in the first person plural, and using [[anaphora]] mixed with [[metaphor]] that hearkens back to Greek political speeches. Hamlet seems the most educated in rhetoric of all the characters, using anaphora, as the king does, but also [[asyndeton]] and highly developed metaphors, while at the same time managing to be precise and unflowery (as when he explains his inward emotion to his mother, saying "But I have that within which passes show, / These but the trappings and the suits of woe."). His language is very self conscious, and relies heavily on puns. Especially when pretending to be mad, Hamlet uses puns to reveal his true thoughts, while at the same time hiding them. Psychologists have since associated a heavy use of puns with [[schizophrenia]].<ref>MacCary (1998, 84-85; 89-90).</ref> | ||

| + | [[Hendiadys]], the expression of an idea by the use of two typically independent words, is one rhetorical type found in several places in the play, as in Ophelia's speech after the nunnery scene ("Th'expectancy and rose of the fair state" and "I, of all ladies, most deject and wretched" are two examples). Many scholars have found it odd that Shakespeare would, seemingly arbitrarily, use this rhetorical form throughout the play. ''Hamlet'' was written later in his life, when he was better at matching rhetorical figures with the characters and the plot than early in his career. Wright, however, has proposed that hendiadys is used to heighten the sense of duality in the play.<ref>MacCary (1998, 87-88).</ref> | ||

| + | Hamlet's [[soliloquy|soliloquies]] have captured the attention of scholars as well. Early critics viewed such speeches as [[To be or not to be]] as Shakespeare's expressions of his own personal beliefs. Later scholars, such as Charney, have rejected this theory saying the soliloquies are expressions of Hamlet's thought process. During his speeches, Hamlet interrupts himself, expressing disgust in agreement with himself, and embellishing his own words. He has difficulty expressing himself directly, and instead skirts around the basic idea of his thought. Not until late in the play, after his experience with the pirates, is Hamlet really able to be direct and sure in his speech.<ref>MacCary (1998, 91-93).</ref> | ||

| − | === | + | ===Religious context=== |

| − | + | [[Image:Millais - Ophelia.jpg|thumb|300px|[[John Everett Millais]]' ''[[Ophelia (painting)|Ophelia]]'' (1852) depicts Ophelia's mysterious death by drowning. The clowns' discussion of whether her death was a suicide and whether she merits a Christian burial is at heart a religious topic.]] | |

| − | + | The play makes several references to both [[Catholicism]] and [[Protestantism]], the two most powerful theological forces of the time in Europe. The Ghost describes himself as being in [[purgatory]], and as having died without receiving his [[last rites]]. This, along with Ophelia's burial ceremony, which is uniquely Catholic, make up most of the play's Catholic connections. Some scholars have pointed that revenge tragedies were traditionally Catholic, possibly because of their sources: Spain and Italy, both Catholic nations. Scholars have pointed out that knowledge of the play's Catholicism can reveal important paradoxes in Hamlet's decision process. According to Catholic doctrine, the strongest duty is to God and family. Hamlet's father being killed and calling for revenge thus offers a contradiction: does he avenge his father and kill Claudius, or does he leave the vengeance to God, as his religion requires?<ref>MacCary (1998, 37-38); in the [[New Testament]], see [[Book of Romans|Romans]] 12:19: "'vengeance is mine, I will repay' sayeth the Lord".</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The play's Protestant overtones include its location in Denmark, a Protestant country in Shakespeare's day, though it is unclear whether the fictional Denmark of the play is intended to mirror this fact. The play does mention Wittenburg, which is where Hamlet is attending university, and where [[Martin Luther]] first nailed his [[95 theses]].<ref>MacCary (1998, 38).</ref> One of the more famous lines in the play related to Protestantism is: "There is special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be not now, 'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet will it come—the readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows what is't to leave betimes, let be."<ref>''Hamlet'' (5.2.202-206).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | = | + | In the First Quarto, the same line reads: “There's a predestinate providence in the fall of a sparrow." Scholars have wondered whether Shakespeare was censored, as the word “predestined” appears in this one Quarto of Hamlet, but not in others, and as censoring of plays was far from unusual at the time.<ref name = Blits>Jan H. Blits. ''Introduction. In Deadly Thought: "Hamlet" and the Human Soul.'' (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2001), 3-21</ref> Rulers and religious leaders feared that the doctrine of predestination would lead people to excuse the most traitorous of actions, with the excuse, “God made me do it.” English Puritans, for example, believed that conscience was a more powerful force than the law, due to emphasis that conscience came not from religious or government leaders, but from God directly to the individual. Many leaders at the time condemned the doctrine, as “unfit 'to keepe subjects in obedience to their sovereigns” as people might “openly maintayne that God hath as well pre-destinated men to be trayters as to be kings."<ref>Mark Matheson, "Hamlet and 'A Matter Tender and Dangerous.'" ''Shakespeare Quarterly'' 46 (4) (1995): 383-397.</ref> King James, as well, often wrote about his dislike of Protestant leaders' taste for standing up to kings, seeing it as a dangerous trouble to society.<ref>David Ward, "The King and 'Hamlet.'" ''Shakespeare Quarterly'' 43(3) (1992): 280–302 </ref> Throughout the play, Shakespeare mixes Catholic and Protestant elements, making interpretation difficult. At one moment, the play is Catholic and medieval, in the next, it is logical and Protestant. Scholars continue to debate what part religion and religious contexts play in ''Hamlet''.<ref>MacCary (1998, 37-45).</ref> |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | ====Philosophical issues==== |

| + | [[Image:Michel-eyquem-de-montaigne 1.jpg|thumb|Philosophical ideas in ''Hamlet'' are similar to those of [[Michel de Montaigne]], a contemporary to Shakespeare.]] | ||

| + | Hamlet is often perceived as a [[philosophy|philosophical]] character. Some of the most prominent philosophical theories in ''Hamlet'' are [[relativism]], [[existentialism]], and [[skepticism|scepticism]]. Hamlet expresses a relativist idea when he says to Rosencrantz: "there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so" (2.2.239-240). The idea that nothing is real except in the mind of the individual finds its roots in the Greek [[Sophism|Sophists]], who argued that since nothing can be perceived except through the senses, and all men felt and sensed things differently, truth was entirely relative. There was no absolute truth.<ref>MacCary (1998, 47-48).</ref> This same line of Hamlet's also introduces theories of existentialism. A double-meaning can be read into the word "is," which introduces the question of whether anything "is" or can be if thinking doesn't make it so. This is tied into his [[To be, or not to be]] speech, where "to be" can be read as a question of existence. Hamlet's contemplation on suicide in this scene, however, is more religious than philosophical. He believes that he will continue to exist after death.<ref>MacCary (1998, 28-49).</ref> | ||

| − | + | ''Hamlet'' is perhaps most affected by the prevailing scepticism in Shakespeare's day in response to the Renaissance's [[humanism]]. Humanists living prior to Shakespeare's time had argued that man was godlike, capable of anything. They argued that man was the God's greatest creation. Scepticism toward this attitude is clearly expressed in Hamlet's [[What a piece of work is a man]] speech:<ref name= m49>MacCary (1998, 49).</ref> | |

| − | + | <blockquote><i> | |

| − | + | … this goodly frame the earth seems to me a sterile promontory, this most excellent canopy the air, look you, this brave o'erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire, why it appeareth nothing to me but a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours. What a piece of work is a man—how noble in reason; how infinite in faculties, in form and moving; how express and admirable in action; how like an angel in apprehension; how like a god; the beauty of the world; the paragon of animals. And yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust?</i> (Q2, 2.2.264-274)<ref>Thompson and Taylor (2006, 256-7)</ref></blockquote> | |

| − | + | Scholars have pointed out this section's similarities to lines written by [[Michel de Montaigne]] in his ''[[Essais]]'': | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Who have persuaded [man] that this admirable moving of heavens vaults, that the eternal light of these lampes so fiercely rowling over his head, that the horror-moving and continuall motion of this infinite vaste ocean were established, and contine so many ages for his commoditie and service? Is it possible to imagine so ridiculous as this miserable and wretched creature, which is not so much as master of himselfe, exposed and subject to offences of all things, and yet dareth call himself Master and Emperor.</blockquote> | |

| − | + | Rather than being a direct influence on Shakespeare, however, Montaigne may have been reacting to the same general atmosphere of the time, making the source of these lines one of context rather than direct influence.<ref>Ronald Knowles, "Hamlet and Counter-Humanism." ''Renaissance Quarterly'' 52(4) (1999): 1046–1069.</ref><ref>MacCary (1998, 49).</ref> | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Themes and Significance== | |

| − | + | Hamlet is not only the most famous of Shakespeare's [[tragedy|tragedies]], it is perhaps the most famous tragedy in all modern literature. It is widely viewed as the first "modern" play in that the most significant action in the play is that which takes place inside the mind of the main character. While the action of the play uses the form of the revenge tragedy, the conflict between Hamlet and Claudius is secondary to the conflict that takes place within Hamlet as he struggles to act. Many of Hamlet's doubts about if and when to seek his revenge have a religious undercurrent. He begins by doubting whether the ghost was really his father or a damned spirit trying to send him to eternal damnation. When he does ascertain his uncle's guilt, he happens on the king in prayer, and fails to act fearing that Claudius is repenting of his sins, in which case according to medieval Christian theology, he will be forgiven and go to heaven. Hamlet draws back from his deed, feeling that such an outcome would be reward, not punishment. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | + | Shakespeare's dramatization of Hamlet's conflicted inner world established a benchmark for the purposes of theater that would influence great modern playwrights such as [[Henrik Ibsen]] and [[Anton Chekhov]] as well as psychological novelists like [[Gustave Flaubert]], [[Fyodor Dostoevsky]], and [[Henry James]]. The character of Hamlet remains the most challenging and alluring lead role for actors, and the play continues to intrigue critics and theater goers with its depth of insight and ambiguities that mirror human experience. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

| − | == | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | ;'''Editions of ''Hamlet''''' |

| + | * Edwards, Philip (ed.). ''Hamlet, Prince of Denmark (New Cambridge Shakespeare).'' New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003. ISBN 0521532523 | ||

| + | * Hibbard, G. R. (ed.). ''Hamlet (Oxford's World's Classics).'' New York: Oxford University Press, 1998 (original 1987). ISBN 0192834169 | ||

| + | * Jenkins, Harold (ed.). ''Hamlet'' (Arden Shakespeare, Second Series). London: The Arden Shakespeare, 1982. ISBN 1903436672 | ||

| + | * Thompson, Ann and Neil Taylor (eds.). ''Hamlet, The Texts of 1603 and 1623 (The Arden Shakespeare, Third Series).'' London: The Arden Shakespeare, 2006. ISBN 1904271804 | ||

| − | + | ;'''Secondary Sources''' | |

| − | *Crystal, David, | + | * Blits, Jan H. ''Introduction. In Deadly Thought: "Hamlet" and the Human Soul.'' Lanham, MD: Lexington Books, 2001. ISBN 0739102141 |

| − | *''Hamlet, | + | * Brown, John R. ''Hamlet: A Guide to the Text and its Theatrical Life.'' (Shakespeare Handbooks). Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. ISBN 1403933871 |

| − | *''Hamlet''. | + | * Crystal, David, and Ben Crystal. ''The Shakespeare Miscellany.'' New York: Overlook Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1585677160 |

| − | *''Hamlet''. | + | * Dawson, Anthony B. ''Hamlet (Shakespeare in Performance).'' Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1995 (original 1780). ISBN 978-0719039331 |

| − | *Wilson, John | + | * Duthie, G. I. ''The "Bad" Quarto of "Hamlet: A Critical Study.'' Cambridge University Press, 1975 (original 1941). ISBN 978-0883051535 |

| + | * Dworkin, Martin, "'Stay Illusion': Having Words About Shakespeare On Screen," ''Journal of Aesthetic Education'' 11 (1977): 55. | ||

| + | * Eliot, T. S. "Hamlet and his Problems," in ''The Sacred Wood: Essays in Poetry and Criticism.'' Faber & Gwyer, 1920. | ||

| + | * Foakes, R. A. ''Hamlet versus Lear.'' Cambridge University Press, 2004 (original 1993). ISBN 978-0521607056 | ||

| + | * Halliday, F. E. ''A Shakespeare Companion, 1564-1964.'' Baltimore: Penguin, 1969. ISBN 978-0140530117 | ||

| + | * Jenkins, Harold. ''Hamlet (Arden Shakespeare, Second Series)'' London: The Arden Shakespeare, 1982. ISBN 1903436672 | ||

| + | * Knowles, Ronald. "Hamlet and Counter-Humanism." ''Renaissance Quarterly'' 52(4) (1999): 1046–1069. | ||

| + | * Lennard, John. ''Shakespeare: Hamlet'' (Literature Insights). Humanities-Ebooks, 2007. | ||

| + | * MacCary, W. Thomas. ''"Hamlet": A Guide to the Play.'' Greenwood Guides to Shakespeare ser. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1998. ISBN 0313300828 | ||

| + | * Matheson, Mark. "Hamlet and 'A Matter Tender and Dangerous.'" ''Shakespeare Quarterly'' 46 (4) (1995): 383-397. | ||

| + | * Pennington, Michael. ''Hamlet: A User’s Guide.'' Limelight Editions, 2004. ISBN 978-0879100834 | ||

| + | * Tomm, Nigel. ''Shakespeare's Hamlet Remixed.'' BookSurge, 2006. ISBN 978-1419648922 | ||

| + | * Wilson, John D. ''The Manuscript of Shakespeare's Hamlet.'' Cambridge, 1934. | ||

| + | * Wilson, John D. ''What Happens in Hamlet.'' Cambridge University Press, 1951 (original 1935). ISBN 978-0521091091 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved January 21, 2024. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | * [http://shea.mit.edu/ramparts Hamlet on the Ramparts] - from MIT Shakespeare Project | |

| + | * [http://www.switzersguide.com The Switzer's Guide to Hamlet] – An extra's view of the Royal Shakespeare Company's 2004 production of ''Hamlet'' | ||

| + | * [http://www.webenglishteacher.com/hamlet.html Hamlet @Web English Teacher] | ||

| + | * [http://academia.wikia.com/wiki/Motifs_in_Hamlet Motifs in Hamlet] at Academic Publishing Wiki | ||

| − | [[category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | + | [[Category:Literature]] |

| − | {{ | + | [[category:History]] |

| + | [[Category:Art, music, literature, sports and leisure]] | ||

| + | {{credit|Hamlet|131395972|Critical_Approaches_to_Hamlet|186309639}} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:59, 21 January 2024

Hamlet: Prince of Denmark is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is one of his best-known works, and also one of the most-quoted writings in the English language.[1] Hamlet has been called "the first great tragedy Europe had produced for two thousand years"[2] and it is universally included on lists of the world's greatest books.[3] It is also one of the most widely performed of Shakespeare's plays; for example, it has topped the list of stagings at the Royal Shakespeare Company since 1879.[4] With 4,042 lines and 29,551 words, Hamlet is also the longest Shakespeare play.[5]

Hamlet is a tragedy of the "revenge" genre, yet transcends the form through unprecedented emphasis on the conflicted mind of the title character. In a reversal of dramatic priorities, Hamlet's inner turmoil—his duty to his slain father, his outrage with his morally compromised mother, and his distraction over the prevailing religious imperatives—provide the context for the play's external action. Hamlet's restless mind, unmoored from faith, proves to be an impediment to action, justifying Nietzsche's judgment on Hamlet that "one who has gained knowledge . . . feel[s] it to be ridiculous or humiliating [to] be asked to set right a world that is out of joint." [6] Hamlet's belated decision to act, his blundering murder of the innocent Polonius, sets in motion the inexorable tragedy of madness, murder, and dissolution of the moral order.

Sources

The story of the Danish prince, "Hamlet," who plots revenge on his uncle, the current king, for killing his father, the former king, is an old one. Many of the story elements, from Hamlet's feigned madness, his mother's hasty marriage to the usurper, the testing of the prince's madness with a young woman, the prince talking to his mother and killing a hidden spy, and the prince being sent to England with two retainers and substituting for the letter requesting his execution for one requesting theirs are already here in this medieval tale, recorded by Saxo Grammaticus in his Gesta Danorum around 1200. A reasonably accurate version of Saxo was rendered into French in 1570 by François de Belleforest in his Histoires Tragiques.[7]

Shakespeare's main source, however, is believed to have been an earlier play—now lost (and possibly by Thomas Kyd)—known as the Ur-Hamlet. This earlier Hamlet play was in performance by 1589, and seems to have introduced a ghost for the first time into the story.[8] Scholars are unable to assert with any confidence how much Shakespeare took from this play, how much from other contemporary sources (such as Kyd's The Spanish Tragedy), and how much from Belleforest (possibly something) or Saxo (probably nothing). In fact, popular scholar Harold Bloom has advanced the (as yet unpopular) notion that Shakespeare himself wrote the Ur-Hamlet as a form of early draft.[9] No matter the sources, Shakespeare's Hamlet has elements that the medieval version does not, such as the secrecy of the murder, a ghost that urges revenge, the "other sons" (Laertes and Fortinbras), the testing of the king via a play, and the mutually fatal nature of Hamlet's (nearly incidental) "revenge."[10][11]

Date and Texts

Hamlet was entered into the Register of the Worshipful Company of Stationers and Newspaper Makers on July 26, 1602. A so-called "bad" First Quarto (referred to as "Q1") was published in 1603, by the booksellers Nicholas Ling and John Trundell. Q1 contains just over half of the text of the later Second Quarto ("Q2") published in 1604,[12] again by Nicholas Ling. Reprints of Q2 followed in 1611 (Q3) and 1637 (Q5); there was also an undated Q4 (possibly from 1622). The First Folio text (often referred to as "F1") appeared as part of Shakespeare's collected plays published in 1623. Q1, Q2, and F1 are the three elements in the textual problem of Hamlet.

The play was revived early in the Restoration era; Sir William Davenant staged a 1661 production at Lincoln's Inn Fields. David Garrick mounted a version at Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in 1772 that omitted the gravediggers and expanded his own leading role. William Poel staged a production of the Q1 text in 1881.[13]

There are three extant texts of Hamlet from the early 1600s: the "first quarto" Hamlet of 1603 (called "Q1"), the "second quarto" Hamlet of 1604/5 ("Q2"), and the Hamlet text within the First Folio of 1623 ("F1"). Later quartos and folios are considered derivative of these, so are of little interest in capturing Shakespeare's original text. Q1 itself has been viewed with skepticism, and in practice Q2 and F1 are the editions upon which editors mostly rely. However, these two versions have some significant differences that have produced a growing body of commentary, starting with early studies by J. Dover Wilson and G. I. Duthie, and continuing into the present.

Early editors of Shakespeare's works, starting with Nicholas Rowe (1709) and Lewis Theobald (1733), combined material from the two earliest known sources of Hamlet, Q2 and F1. Each text contains some material the other lacks, and there are many minor differences in wording, so that only a little more than two hundred lines are identical between them. Typically, editors have taken an approach of combining, "conflating," the texts of Q2 and F1, in an effort to create an inclusive text as close as possible to the ideal Shakespeare original. Theobald's version became standard for a long time.[14] Certainly, the "full text" philosophy that he established has influenced editors to the current day. Many modern editors have done essentially the same thing Theobald did, also using, for the most part, the 1604/5 quarto and the 1623 folio texts.

The discovery of Q1 in 1823,[15] when its existence had not even been suspected earlier, caused considerable interest and excitement, while also raising questions. The deficiencies of the text were recognized immediately—Q1 was instrumental in the development of the concept of a Shakespeare "bad quarto." Yet Q1 also has its value: it contains stage directions which reveal actual stage performance in a way that Q2 and F1 do not, and it contains an entire scene (usually labeled IV, vi) that is not in either Q2 or F1. Also, Q1 is useful simply for comparison to the later publications. At least 28 different productions of the Q1 text since 1881 have shown it eminently fit for the stage. Q1 is generally thought to be a "memorial reconstruction" of the play as it may have been performed by Shakespeare's own company, although there is disagreement whether the reconstruction was pirated or authorized. It is considerably shorter than Q2 or F1, apparently because of significant cuts for stage performance. It is thought that one of the actors playing a minor role (Marcellus, certainly, perhaps Voltemand as well) in the legitimate production was the source of this version.

Another theory is that the Q1 text is an abridged version of the full length play intended especially for traveling productions (the aforementioned university productions, in particular.) Kathleen Irace espouses this theory in her New Cambridge edition, "The First Quarto of Hamlet." The idea that the Q1 text is not riddled with error, but is in fact a totally viable version of the play has led to several recent Q1 productions (perhaps most notably, Tim Sheridan and Andrew Borba's 2003 production at the Theatre of NOTE in Los Angeles, for which Ms. Irace herself served as dramaturg).[16]

As with the two texts of King Lear, some contemporary scholarship is moving away from the ideal of the "full text," supposing its inapplicability to the case of Hamlet. The Arden Shakespeare's 2006 publication of different texts of Hamlet in different volumes is perhaps the best evidence of this shifting focus and emphasis.[17] However, any abridgement of the standard conflation of Q2 and F1 runs the obvious risk of omitting genuine Shakespeare writing.

Performance History

The earliest recorded performance of Hamlet was in June 1602; in 1603 the play was acted at both universities, Cambridge and Oxford. Along with Richard II, Hamlet was acted by the crew of Capt. William Keeling aboard the British East India Company ship Dragon, off Sierra Leone, in September 1607. More conventional Court performances occurred in 1619 and in 1637, the latter on January 24 at Hampton Court Palace. Since Hamlet is second only to Falstaff among Shakespeare's characters in the number of allusions and references to him in contemporary literature, the play was certainly performed with a frequency missed by the historical record.[18]

Actors who have played Hamlet include Laurence Olivier, (1937) John Gielgud (1939), Mel Gibson, and Derek Jacobi (1978), who played the title role of Hamlet at Elsinore Castle in Denmark, the actual setting of the play. Christopher Plummer also played the role in a television version (1966) that was filmed there. Actresses who have played the title role in Hamlet include Sarah Siddons, Sarah Bernhardt, Asta Nielsen, Judith Anderson, Diane Venora and Frances de la Tour. The youngest actor to play the role on film was Ethan Hawke, who was 29, In Hamlet (2000). The oldest is probably Johnston Forbes-Robertson, who was 60 when his performance was filmed in 1913.[19] Edwin Booth, the brother of John Wilkes Booth's (the man who assassinated Abraham Lincoln), went into a brief retirement after his brother's notoriety, but made his comeback in the role of Hamlet. Rather than wait for Hamlet's first appearance in the text to meet the audience's response, Booth sat on the stage in the play's first scene and was met by a lengthy standing ovation.

Booth's Broadway run of Hamlet lasted for one hundred performances in 1864, an incredible run for its time. When John Barrymore played the part on Broadway to acclaim in 1922, it was assumed that he would close the production after 99 performances out of respect for Booth. But Barrymore extended the run to 101 performances so that he would have the record for himself. Currently, the longest Broadway run of Hamlet is the 1964 production starring Richard Burton and directed by John Gielgud, which ran for 137 performances. The actor who has played the part most frequently on Broadway is Maurice Evans, who played Hamlet for 267 performances in productions mounted in 1938, 1939, and 1945. The longest recorded London run is that of Henry Irving, who played the part for over two hundred consecutive nights in 1874 and revived it to acclaim with Ellen Terry as Ophelia in 1878.

The only actor to win a Tony Award for playing Hamlet is Ralph Fiennes in 1995. Burton was nominated for the award in 1964, but lost to Sir Alec Guinness in Dylan. Hume Cronyn won the Tony Award for his performance as Polonius in that production. The only actor to win an Academy Award for playing Hamlet is Laurence Olivier in 1948. The only actor to win an Emmy Award nomination for playing Hamlet is Christopher Plummer in 1966. Margaret Leighton won an Emmy for playing Gertrude in the 1971 Hallmark Hall of Fame presentation.

Characters

Main characters include:

- Hamlet, the title character, is the son of the late king, for whom he was named. He has returned to Elsinore Castle from Wittenberg, where he was a university student.

- Claudius is the king of Denmark, elected to the throne after the death of his brother, King Hamlet. Claudius has married Gertrude, his brother's widow.

- Gertrude is the queen of Denmark, and King Hamlet's widow, now married to Claudius.

- The Ghost appears in the exact image of Hamlet's father, the late King Hamlet.

- Polonius is Claudius's chief advisor, and the father of Ophelia and Laertes (this character is called "Corambis" in the First Quarto of 1603).

- Laertes is the son of Polonius, and has returned to Elsinore Castle after living in Paris.

- Ophelia is Polonius's daughter, and Laertes's sister, who lives with her father at Elsinore Castle.

- Horatio is a good friend of Hamlet, from Wittenberg, who came to Elsinore Castle to attend King Hamlet's funeral.

- 'Rosencrantz and Guildenstern' are childhood friends and schoolmates of Hamlet, who were summoned to Elsinore by Claudius and Gertrude.

Synopsis

The play is set at Elsinore Castle, which is based on the real Kronborg Castle, Denmark. The time period of the play is somewhat uncertain, but can be understood as mostly Renaissance, contemporary with Shakespeare's England.

Hamlet begins with Francisco on watch duty at Elsinore Castle, on a cold, dark night, at midnight. Barnardo approaches Francisco to relieve him on duty, but is unable to recognize his friend at first in the darkness. Barnardo stops and cries out, "Who's there?" The darkness and the mystery, of "who's there," set an ominous tone to start the play.

That same night, Horatio and the sentinels see a ghost that looks exactly like their late king, King Hamlet. The Ghost reacts to them, but doesn't speak. The men discuss a military buildup in Denmark in response to Fortinbras recruiting an army. Although Fortinbras's army is supposedly for use against Poland, they fear he may attack Denmark to get revenge for his father's death, and reclaim the land his father lost to King Hamlet. They wonder if the Ghost is an omen of disaster, and decide to tell Prince Hamlet about it.

In the next scene, Claudius announces that the mourning period for his brother is officially over, and he also sends a diplomatic mission to Norway, to try to deal with the potential threat from Fortinbras. Claudius and Hamlet have an exchange in which Hamlet says his line, "a little more than kin and less than kind." Gertrude asks Hamlet to stay at Elsinore Castle, and he agrees to do so, despite his wish to return to school in Wittenberg. Hamlet, upset over his father's death and his mother's "o'erhasty" marriage to Claudius, recites a soliloquy including "Frailty, thy name is woman." Horatio and the sentinels tell Hamlet about the Ghost, and he decides to go with them that night to see it.

Laertes leaves to return to France after lecturing Ophelia against Hamlet. Polonius, suspicious of Hamlet's motives, also lectures her against him, and forbids her to have any further contact with Hamlet.

That night, Hamlet, Horatio and Marcellus do see the Ghost again, and it beckons to Hamlet. Marcellus says his famous line, "Something is rotten in the state of Denmark." They try to stop Hamlet from following, but he does.

The Ghost speaks to Hamlet, calls for revenge, and reveals Claudius's murder of Hamlet's father. The Ghost also criticizes Gertrude, but says "leave her to heaven." The Ghost tells Hamlet to remember, says adieu, and disappears. Horatio and Marcellus arrive, but Hamlet refuses to tell them what the Ghost said. In an odd, much-discussed passage, Hamlet asks them to swear on his sword while the Ghost calls out "swear" from the earth beneath their feet. Hamlet says he may put on an "antic disposition."

We then find Polonius sending Reynaldo to check up on what Laertes is doing in Paris. Ophelia enters, and reports that Hamlet rushed into her room with his clothing all askew, and only stared at her without speaking. Polonius decides that Hamlet is mad for Ophelia, and says he'll go to the king about it.

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern arrive, and are instructed by Claudius and Gertrude to spend time with Hamlet and sound him out. Polonius announces that the ambassadors have returned from Norway with an agreement. Polonius tells Claudius that Hamlet is mad over Ophelia, and recommends an eavesdropping plan to find out more. Hamlet enters, "mistaking" Polonius for a "fishmonger." Rosencrantz and Guildenstern talk to Hamlet, who quickly discerns they're working for Claudius and Gertrude. The Players arrive, and Hamlet decides to try a play performance, to "catch the conscience of the king."

In the next scene, Hamlet recites his famous "To be or not to be" soliloquy. The famous “Nunnery Scene,” then occurs, in which Hamlet speaks to Ophelia while Claudius and Polonius hide and listen. Instead of expressing love for Ophelia, Hamlet rejects and berates her, tells her "get thee to a nunnery" and storms out. Claudius decides to send Hamlet to England.

Next, Hamlet instructs the Players how to do the upcoming play performance, in a passage that has attracted interest because it apparently reflects Shakespeare's own views of how acting should be done. The play begins, during which Hamlet sits with Ophelia, and makes "mad" sexual jokes and remarks. Claudius asks the name of the play, and Hamlet says "The Mousetrap." Claudius walks out in the middle of the play, which Hamlet sees as proof of Claudius's guilt. Hamlet recites his dramatic "witching time of night" soliloquy.

Next comes the “Prayer Scene,” in which Hamlet finds Claudius, intending to kill him, but refrains because Claudius is praying. Hamlet then goes to talk to Gertrude, in the “Closet Scene.” There, Gertrude becomes frightened of Hamlet, and screams for help. Polonius is hiding behind an arras in the room, and when he also yells for help, Hamlet stabs and kills him. Hamlet emotionally lectures Gertrude, and the Ghost appears briefly, but only Hamlet sees it. Hamlet drags Polonius's body out of Gertrude's room, to take it elsewhere.

When Claudius learns of the death of Polonius, he decides to send Hamlet to England immediately, accompanied by Rosencrantz and Guildenstern. They carry a secret order from Claudius to England to execute Hamlet.

In a scene which appears at full length only in the Second Quarto, Hamlet sees Fortinbras arrive in Denmark with his army, speaks to a captain, then exits with Rosencrantz and Guildenstern to board the ship to England.

Next, Ophelia appears, and she has gone mad, apparently in grief over the death of her father. She sings odd songs about death and sex, says "good night" during the daytime, and exits. Laertes, who has returned from France, storms the castle with a mob from the local town, and challenges Claudius, over the death of Polonius. Ophelia appears again, sings, and hands out flowers. Claudius tells Laertes that he can explain his innocence in Polonius's death.

Sailors (pirates) deliver a letter from Hamlet to Horatio, saying that Hamlet's ship was attacked by pirates, who took him captive, but are returning him to Denmark. Horatio leaves with the pirates to go where Hamlet is.

Claudius has explained to Laertes that Hamlet is responsible for Polonius's death. Claudius, to his surprise, receives a letter saying that Hamlet is back. Claudius and Laertes conspire to set up a fencing match at which Laertes can kill Hamlet in revenge for the death of Polonius. Gertrude reports that Ophelia is dead, after a fall from a tree into the brook, where she drowned.

Two clowns, a sexton and a bailiff, make jokes and talk about Ophelia's death while the sexton digs her grave. They conclude she must have committed suicide. Hamlet, returning with Horatio, sees the grave being dug (without knowing who it's for), talks to the sexton, and recites his famous "alas, poor Yorick" speech. Hamlet and Horatio hide to watch as Ophelia's funeral procession enters. Laertes jumps into the grave excavation for Ophelia, and proclaims his love for her in high-flown terms. Hamlet challenges Laertes that he loved Ophelia more than "forty thousand" brothers could, and they scuffle briefly. Claudius calms Laertes, and reminds him of the rigged fencing match they've arranged to kill Hamlet.

In the final scene, Hamlet explains to Horatio that he became suspicious about the trip to England, and looked at the royal commission during the night when Rosencrantz and Guildenstern were asleep. After discovering the truth, Hamlet substituted a forgery, ordering England to kill Rosencrantz and Guildenstern instead of him. Osric then tells Hamlet of the fencing match, and despite his misgivings, Hamlet agrees to participate.

At the match, Claudius and Laertes have arranged for Laertes to use a poisoned foil, and Claudius also poisons Hamlet's wine, in case the poisoned foil doesn't work. The match begins, and Hamlet scores the first hit, "a very palpable hit." Gertrude sips from Hamlet's poisoned wine to salute him. Laertes wounds Hamlet with the poisoned foil, then they grapple and exchange foils, and Hamlet wounds Laertes, with the same poisoned foil. Gertrude announces that she's been poisoned by the wine, and dies. Laertes, also dying, reveals that Claudius is to blame, and asks Hamlet to exchange forgiveness with him, which Hamlet does. Laertes dies.

Hamlet wounds Claudius with the poisoned foil, and also has him drink the wine he poisoned. Claudius dies. Hamlet, dying of his injury from the poisoned foil, says he supports Fortinbras as the next king, and that "the rest is silence." When Hamlet dies, Horatio says, "flights of angels sing thee to thy rest." Fortinbras enters, with ambassadors from England who announce that Rosencrantz and Guildenstern are dead. Fortinbras takes over, says that Hamlet would have "proved most royal," and orders a salute to be fired, which concludes the play.

Analysis and criticism

Dramatic structure

In creating Hamlet, Shakespeare broke several rules, one of the largest being the rule of action over character. In his day, plays were usually expected to follow the advice of Aristotle in his Poetics, which declared that a drama should not focus on character so much as action. The highlights of Hamlet, however, are not the action scenes, but the soliloquies, wherein Hamlet reveals his motives and thoughts to the audience. Also, unlike Shakespeare's other plays, there is no strong subplot; all plot forks are directly connected to the main vein of Hamlet struggling to gain revenge. The play is full of seeming discontinuities and irregularities of action. At one point, Hamlet is resolved to kill Claudius: in the next scene, he is suddenly tame. Scholars still debate whether these odd plot turns are mistakes or intentional additions to add to the play's theme of confusion and duality.[20]

Language

Much of the play's language is in the elaborate, witty language expected of a royal court. This is in line with Baldassare Castiglione's work, The Courtier (published in 1528), which outlines several courtly rules, specifically advising servants of royals to amuse their rulers with their inventive language. Osric and Polonius seem to especially respect this suggestion. Claudius' speech is full of rhetorical figures, as is Hamlet's and, at times, Ophelia's, while Horatio, the guards, and the gravediggers use simpler methods of speech. Claudius demonstrates an authoritative control over the language of a King, referring to himself in the first person plural, and using anaphora mixed with metaphor that hearkens back to Greek political speeches. Hamlet seems the most educated in rhetoric of all the characters, using anaphora, as the king does, but also asyndeton and highly developed metaphors, while at the same time managing to be precise and unflowery (as when he explains his inward emotion to his mother, saying "But I have that within which passes show, / These but the trappings and the suits of woe."). His language is very self conscious, and relies heavily on puns. Especially when pretending to be mad, Hamlet uses puns to reveal his true thoughts, while at the same time hiding them. Psychologists have since associated a heavy use of puns with schizophrenia.[21]

Hendiadys, the expression of an idea by the use of two typically independent words, is one rhetorical type found in several places in the play, as in Ophelia's speech after the nunnery scene ("Th'expectancy and rose of the fair state" and "I, of all ladies, most deject and wretched" are two examples). Many scholars have found it odd that Shakespeare would, seemingly arbitrarily, use this rhetorical form throughout the play. Hamlet was written later in his life, when he was better at matching rhetorical figures with the characters and the plot than early in his career. Wright, however, has proposed that hendiadys is used to heighten the sense of duality in the play.[22]

Hamlet's soliloquies have captured the attention of scholars as well. Early critics viewed such speeches as To be or not to be as Shakespeare's expressions of his own personal beliefs. Later scholars, such as Charney, have rejected this theory saying the soliloquies are expressions of Hamlet's thought process. During his speeches, Hamlet interrupts himself, expressing disgust in agreement with himself, and embellishing his own words. He has difficulty expressing himself directly, and instead skirts around the basic idea of his thought. Not until late in the play, after his experience with the pirates, is Hamlet really able to be direct and sure in his speech.[23]

Religious context

The play makes several references to both Catholicism and Protestantism, the two most powerful theological forces of the time in Europe. The Ghost describes himself as being in purgatory, and as having died without receiving his last rites. This, along with Ophelia's burial ceremony, which is uniquely Catholic, make up most of the play's Catholic connections. Some scholars have pointed that revenge tragedies were traditionally Catholic, possibly because of their sources: Spain and Italy, both Catholic nations. Scholars have pointed out that knowledge of the play's Catholicism can reveal important paradoxes in Hamlet's decision process. According to Catholic doctrine, the strongest duty is to God and family. Hamlet's father being killed and calling for revenge thus offers a contradiction: does he avenge his father and kill Claudius, or does he leave the vengeance to God, as his religion requires?[24]

The play's Protestant overtones include its location in Denmark, a Protestant country in Shakespeare's day, though it is unclear whether the fictional Denmark of the play is intended to mirror this fact. The play does mention Wittenburg, which is where Hamlet is attending university, and where Martin Luther first nailed his 95 theses.[25] One of the more famous lines in the play related to Protestantism is: "There is special providence in the fall of a sparrow. If it be not now, 'tis not to come; if it be not to come, it will be now; if it be not now, yet will it come—the readiness is all. Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows what is't to leave betimes, let be."[26]

In the First Quarto, the same line reads: “There's a predestinate providence in the fall of a sparrow." Scholars have wondered whether Shakespeare was censored, as the word “predestined” appears in this one Quarto of Hamlet, but not in others, and as censoring of plays was far from unusual at the time.[27] Rulers and religious leaders feared that the doctrine of predestination would lead people to excuse the most traitorous of actions, with the excuse, “God made me do it.” English Puritans, for example, believed that conscience was a more powerful force than the law, due to emphasis that conscience came not from religious or government leaders, but from God directly to the individual. Many leaders at the time condemned the doctrine, as “unfit 'to keepe subjects in obedience to their sovereigns” as people might “openly maintayne that God hath as well pre-destinated men to be trayters as to be kings."[28] King James, as well, often wrote about his dislike of Protestant leaders' taste for standing up to kings, seeing it as a dangerous trouble to society.[29] Throughout the play, Shakespeare mixes Catholic and Protestant elements, making interpretation difficult. At one moment, the play is Catholic and medieval, in the next, it is logical and Protestant. Scholars continue to debate what part religion and religious contexts play in Hamlet.[30]

Philosophical issues

Hamlet is often perceived as a philosophical character. Some of the most prominent philosophical theories in Hamlet are relativism, existentialism, and scepticism. Hamlet expresses a relativist idea when he says to Rosencrantz: "there is nothing either good or bad but thinking makes it so" (2.2.239-240). The idea that nothing is real except in the mind of the individual finds its roots in the Greek Sophists, who argued that since nothing can be perceived except through the senses, and all men felt and sensed things differently, truth was entirely relative. There was no absolute truth.[31] This same line of Hamlet's also introduces theories of existentialism. A double-meaning can be read into the word "is," which introduces the question of whether anything "is" or can be if thinking doesn't make it so. This is tied into his To be, or not to be speech, where "to be" can be read as a question of existence. Hamlet's contemplation on suicide in this scene, however, is more religious than philosophical. He believes that he will continue to exist after death.[32]

Hamlet is perhaps most affected by the prevailing scepticism in Shakespeare's day in response to the Renaissance's humanism. Humanists living prior to Shakespeare's time had argued that man was godlike, capable of anything. They argued that man was the God's greatest creation. Scepticism toward this attitude is clearly expressed in Hamlet's What a piece of work is a man speech:[33]

… this goodly frame the earth seems to me a sterile promontory, this most excellent canopy the air, look you, this brave o'erhanging firmament, this majestical roof fretted with golden fire, why it appeareth nothing to me but a foul and pestilent congregation of vapours. What a piece of work is a man—how noble in reason; how infinite in faculties, in form and moving; how express and admirable in action; how like an angel in apprehension; how like a god; the beauty of the world; the paragon of animals. And yet, to me, what is this quintessence of dust? (Q2, 2.2.264-274)[34]

Scholars have pointed out this section's similarities to lines written by Michel de Montaigne in his Essais:

Who have persuaded [man] that this admirable moving of heavens vaults, that the eternal light of these lampes so fiercely rowling over his head, that the horror-moving and continuall motion of this infinite vaste ocean were established, and contine so many ages for his commoditie and service? Is it possible to imagine so ridiculous as this miserable and wretched creature, which is not so much as master of himselfe, exposed and subject to offences of all things, and yet dareth call himself Master and Emperor.

Rather than being a direct influence on Shakespeare, however, Montaigne may have been reacting to the same general atmosphere of the time, making the source of these lines one of context rather than direct influence.[35][36]

Themes and Significance

Hamlet is not only the most famous of Shakespeare's tragedies, it is perhaps the most famous tragedy in all modern literature. It is widely viewed as the first "modern" play in that the most significant action in the play is that which takes place inside the mind of the main character. While the action of the play uses the form of the revenge tragedy, the conflict between Hamlet and Claudius is secondary to the conflict that takes place within Hamlet as he struggles to act. Many of Hamlet's doubts about if and when to seek his revenge have a religious undercurrent. He begins by doubting whether the ghost was really his father or a damned spirit trying to send him to eternal damnation. When he does ascertain his uncle's guilt, he happens on the king in prayer, and fails to act fearing that Claudius is repenting of his sins, in which case according to medieval Christian theology, he will be forgiven and go to heaven. Hamlet draws back from his deed, feeling that such an outcome would be reward, not punishment.

Shakespeare's dramatization of Hamlet's conflicted inner world established a benchmark for the purposes of theater that would influence great modern playwrights such as Henrik Ibsen and Anton Chekhov as well as psychological novelists like Gustave Flaubert, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Henry James. The character of Hamlet remains the most challenging and alluring lead role for actors, and the play continues to intrigue critics and theater goers with its depth of insight and ambiguities that mirror human experience.

Notes

- ↑ Hamlet has 208 quotations in the Oxford Dictionary of Quotations; it takes up 10 of 85 pages dedicated to Shakespeare in the 1986 Bartlett's Familiar Quotations.

- ↑ Frank Kermode, "Hamlet, Prince of Denmark," from The Riverside Shakespeare. (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1974 ISBN 0-39504402-2) 1135

- ↑ Harvard Classics, Great Books. Great Books of the Western World; Harold Bloom's The Western Canon; Columbia College Core Curriculum.

- ↑ David Crystal and Ben Crystal. The Shakespeare Miscellany (New York: Overlook Press, 2005. ISBN 978-1585677160), 66.

- ↑ Based on the first edition of The Riverside Shakespeare (Houghton Mifflin Company, 1974).

- ↑ Friedrich Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, quoted in Harold Bloom, Shakespeare: The Birth of the Human (New York: Riverhead, 1998 ISBN 1573221201) 393-394

- ↑ Philip Edwards. Hamlet, Prince of Denmark. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0521532523), 1-2.

- ↑ Harold Jenkins. Hamlet (Arden Shakespeare, Second Series) (London: The Arden Shakespeare, 1982, ISBN 1903436672), 82-85.

- ↑ Bloom advances this theory in both his major popular works on Shakespeare, Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human. (New York: Riverhead Books, 1998, ISBN 1573221201) and Hamlet: Poem Unlimited. (New York: Riverhead Books, 2003, ISBN 157322233X).

- ↑ Edwards, 2.

- ↑ See Jenkins, 82-122 for a complex discussion of all sorts of possible influences that found their way into the play.

- ↑ Some copies of Q2 are dated 1605, possibly reflecting a second impression; so that Q2 is often dated "1604/5."

- ↑ F. E. Halliday. A Shakespeare Companion, 1564-1964. (Baltimore: Penguin, 1969, ISBN 978-0140530117), 204.

- ↑ G. R. Hibbard, (ed.), Hamlet (Oxford's World's Classics). (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987, reprinted 1998, ISBN 0192834169), 22-23.

- ↑ Jenkins, 14.