Gunpowder

Gunpowder is a low explosive that burns rapidly, releasing gases that act as a propellant in firearms. As it burns, a subsonic deflagration wave is produced rather than the supersonic detonation wave which high explosives produce. As a result, pressures generated inside a gun are sufficient to propel a bullet, but not sufficient to destroy the barrel. At the same time, this makes gunpowder less suitable for shattering rock or fortifications, applications where "high" explosives (called as brisant in chemistry, e.g. TNT) are preferred.

Definition

The Oxford English Dictionary defines the English word gunpowder as "An explosive mixture of saltpetre, sulphur, and charcoal, chiefly used in discharging projectiles from guns and for blasting."[1] Defined this way, the word gunpowder is essentially synonymous with black powder.

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English language defines gunpowder as "Any of various explosive powders used to propel projectiles from guns, especially a black mixture of potassium nitrate, charcoal, and sulfur."[2]

Biochemist and scientific historian Joseph Needham[3] uses the word gunpowder to refer not only to the explosive as defined by the Oxford English Dictionary, but also to previous concoctions (outlined in 5 stages) of combustible material mixed with saltpeter. The first three stages Needham calls "proto-gunpowders," advocating his view of the evolution of low-nitrate, low carbon proto-gunpowders into modern forms of gunpowder with higher levels of nitrate and carbon in the form of charcoal.[4]. After the third stage (in the 11th century), a formula closer to that of modern gunpowder, with higher levels of saltpeter, takes form. From this perspective, Needham outlines the evolutionary stages of gunpowder formulas over time, with different levels of combustion:

- Slow burning

- Old incendiaries using oil, pitch, sulfur, etc., which Needham asserts would have been the available concoction used by the 10th century for the launching of Chinese Fire Arrows in warfare.[5]

- Quick burning

- Distilled petroleum or naptha (i.e. Greek Fire), a slightly more effective incendiary used in hurled, breakable earthenware pots or in the igniting of double-piston flamethrowers used in China by the 10th century,[5] when the formula of Greek Fire was spread to China from the Arabs, Arabia being one of China's maritime contacts through the Indian Ocean since the 7th century.[6]

- Deflagration

- Low-nitrate powders that are still considered incendiary, but now contain charcoal. This is the turning point from which proto-gunpowder turns into mixtures he calls "true gunpowder".[5] A Chinese book of 1044 C.E. (the Wujing Zongyao described in the section below) was the first to record saltpeter explosives including sulfur and charcoal, although many other ingredients were included in the mixture.[7] For example, a certain mixture filling a soft-casing bomb in the Wujing Zongyao had 20 oz. of sulfur, 40 oz. of saltpetre, 5 oz. of charcoal, and 14.7 oz. of additional substances (such as tung oil and pitch).[7]

- Explosion

- This mixture has a considerably higher proportion of potassium nitrate to combustible material (for example, a mixture of sulfur, saltpetre, charcoal, arsenic, and other materials). This explosion has the potential to burst through thin-walled containers of cast iron or other metals.[5] Such mixtures were created in China by the 12th century and used frequently in warfare.

- Detonation

- This stage is when the nitrate content of a gunpowder solution has reached the level of 'modern gunpowder', meaning the proportion of saltpetre, sulfur, and charcoal follow the ratio of 75:15:10 respectively, and are the sole ingredients of the formula.[5] Thin metal containers burst with a loud noise, tearing, scattering, and leaving debris, while it is now a full propellant suitable for cannons and guns having metal barrels of considerable strength.[5] As seen in the following sections, by the 14th century China, Europe, India, and the Islamic world employed its use in warfare.

History and development

The invention and diffusion of gunpowder technology

The earliest clear, certain references to saltpetre explosives come from China. Joseph Needham argues that ancient Chinese alchemists were probably the first to develop an early form of gunpowder, as part of their search for elixirs of immortality. He notes that only in China was there evidence of the precursors of black powder (Needham's 'proto-gunpowders' and early 'true gunpowders'), while in Europe, black powder is noted to appear suddenly and already relatively developed in recipes incorporating saltpeter, sulfur and charcoal (and early on, other adulterants).[8] Needham calls gunpowder one of the Four Great Inventions of ancient China.

The word 'gunpowder', widely defined, should include all mixtures of saltpetre, sulphur and carbonaceous material; but any composition not containing charcoal, as for example those which incorporated honey, may be termed 'proto-gunpowder'. Our word gunpowder arises from the fact that Europe knew it only for cannon or hand-guns. In China, however prototype mixtures were known to alchemists, physicians and perhaps fireworks technicians, for their deflagrative properties, some time before they began to be used as weapons. Hence the Chinese name for gunpowder, huo yao, literally 'fire-chemical' or 'fire drug'.

Adoption of this definition and historical perspective places the invention of gunpowder in China, no later than the eleventh century. Use of the stricter definition offered by the Oxford English Dictionary, however, leaves the precise question of the time and place of gunpowder's invention open. Although the earliest clear, written reference to black powder by itself, without other ingredients, was by Roger Bacon in England in 1267, he implies that he did not invent it himself, and that the technology was already widespread in his time.[9][10]

There is no direct record of how the modern formula for black powder was invented, or how it came to be known in Europe and Asia, but most scholars believe that saltpeter explosives developed into an early form of black powder in China, and that this technology spread west from China to the Middle East and then Europe, possibly via the Silk Road.[11][12][8] Bert S. Hall promotes the view that many cultures contributed to the development of gunpowder in its ultimate form.

Gunpowder is not, of course, an 'invention' in the modern sense, the product of a single time and place; no individual's name can be attached to it, nor can that of any single nation or region. Fire is one of the primordial forces of nature, and incendiary weapons have had a place in armies' toolkits for almost as long as civilized states have made war.[13]

China

The facilitation of combustion by addition of saltpeter was discovered very early in China. An early record of Chinese alchemical experimentation comes from a Han era book The Kinship of the Three compiled in 142 C.E. by Wei Boyang[14][15], where he recorded experiments in which a set of ingredients were said to "fly and dance" in a violent reaction. By 300 C.E., Ge Hong, an alchemist of the Jin dynasty conclusively recorded the chemical reactions caused when saltpeter, redwood and charcoal were heated together in his book "Book of the Master of the Preservations of Solidarity".[16] A ninth-century record of Chinese experimentation with saltpetre, the "Classified Essentials of the Mysterious Tao of the True Origin of Things," indicates that saltpeter-aided combustion was an unintended byproduct of Taoist alchemical efforts to develop an elixir of immortality:[17]

Some have heated together sulfur, realgar and saltpeter with honey; smoke and flames result, so that their hands and faces have been burnt, and even the whole house where they were working burned down.[18]

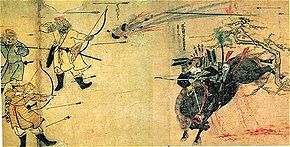

The accidental discovery in the ninth century of saltpeter's combustion-enhancing property coincided with a long period of disunity during which there was some immediate use for infantry and siege weapons.[19] The years 904–6 saw the use of incendiary projectiles called 'flying fires' (fei-huo).[20] One early application was the fire lance, a handheld flamethrower which could also be loaded with shrapnel, and first depicted in Chinese artwork by c. 950 C.E.;[21] by the late thirteenth century the Chinese developed these into guns.[22]

In 932 C.E., at the Battle of Lang-shan Jiang (Wolf Mountain River), the naval fleet of the Wen-Mu King was defeated by Qian Yuan-guan because he had used an incendiary called 'fire oil' (hǔo yóu, 火油), identified by Needham as Greek fire, to burn his fleet.[23] Needham argues that an early form of gunpowder, "identified all but infallibly by the term huo yao," was used in the ignition chamber. His historical source for this argument is the Song Dynasty treatise entitled Wu Ching Tsung Yao (Wujing Zongyao, 武经总要), written by Tseng Kung-Liang (Zeng Gongliang) and Yang Weide in 1044 C.E. Kung-Liang, describes a "fierce fire oil shooter," which includes an "ignition chamber" filled with huo yao. Needham's argument is that this is the device employed at the naval battle at Lang-shan Jiang. If that is correct, then the passage, following Needham's definition of gunpowder, "probably implies the first use of gunpowder in warfare in China." [24] Needham does not offer any speculation in this passage that the recipe for the huo yao was different from or more refined than the other forms of huo yao described in the Wu Ching Tsung Yao, except to say that, "Course twine impregnated with saltpetre and slowly burning will of course also do . . . but very low-nitrate gunpowder would work in the same way." [24]

The various Chinese formulas for explosives in the Wu Ching Tsung Yao held levels of nitrate in the range of 27% to 50%.[25] By the end of the 12th century, Chinese formulas for explosives were capable of bursting through cast iron metal containers, in the form of the earliest hollow, grenade bombs filled with these explosives.[26] Grenades were employed in the Battle of Tangdao and the Battle of Caishi on the Yangtze River in 1161 C.E., in which combatants employed soft-case bombs packed with lime and sulfur.[27][28][29]

The Song Dynasty government was frightened by the spread and use of saltpeter explosives by foreign enemies even as far back as the 11th century. As the historical text of the Song Shi (compiled in 1345 C.E.) states, in 1067 C.E. the Song government forbid the people of Hedong (modern Shanxi) and Hebei to sell foreigners any form of sulfur or saltpetre.[30] In 1076 C.E. the Song government issued a ban on all private commercial transactions involving saltpetre and sulfur (fearing they would be sold across the border), creating a government monopoly on their production and commercial distribution.[30]

The first certain recorded use of saltpeter explosives as propellants was in the year 1132, in experiments with mortars consisting of bamboo tubes. Mortars with metal tubes (made of iron or bronze) first appeared in the wars (1268-1279) between the Mongols and the Song Dynasty.[31]

Partington notes that Chao I, in his Kai Yu Ts'ung K'ao of 1790, stated that Wei Xing (d. 1164 C.E.) of the Song Dynasty invented projectile carriages launching 'fire-stones' that employed saltpetre, sulphur, and willow charcoal (i.e. vine charcoal) in its formula, and that, "this was the origin of the pyrotechnics in vogue in modern times." Though Partington does not argue that Chao I's eighteenth-century account of the invention of "modern pyrotechnics" in the twelfth century is accurate, if it is, this would then become the first mention of the gunpowder recipe in its final form, from anywhere in the world. [32]

From the mid 14th century Chinese manuscript known as the Huolongjing 火龙经, a passage refers to the first use of cast iron shell casings for explosive cannon balls, fired by what the Chinese had termed the 'flying-cloud thunderclap eruptor' (feiyun pili pao 飞云霹雳炮):

The shells are made of cast iron, as large as a bowl and shaped like a ball. Inside they contain half a pound of 'magic' gunpowder. They are sent flying towards the enemy camp from an eruptor; and when they get there a sound like a thunder-clap is heard, and flashes of light appear. If ten of these shells are fired successfully into the enemy camp, the whole place will be set ablaze...[33]

Safety measures against the destructive force of these explosives was not fully appreciated by some in China. In the year 1260, the personal arsenal of Song Dynasty Prime Minister Zhao Nanchong had caught fire and exploded, destroying several outlying houses and killing four of his prized tiger pets.[34] An even more alarming event happened in 1280, a year after the Mongol conquests of the Southern Song Dynasty. For that year, the Gui Xin Za Zhi (1295 C.E.) reported that a disaster had struck at the Weiyang arsenal used primarily for the storage of trebuchet-launched bombs:

Formerly the artisan positions were all held by southerners (i.e. the Chinese). But they engaged in peculation, so they had to be dismissed, and all their jobs were given to northerners (probably Mongols, or Chinese who had served them). Unfortunately, these men understood nothing of the handling of chemical substances. Suddenly, one day, while sulphur was being ground fine, it burst into flame, then the (stored) fire lances caught fire, and flashed hither and thither like frightened snakes. (At first) the workers thought it was funny, laughing and joking, but after a short time the fire got into the bomb store, and then there was a noise like a volcanic eruption and the holwing of a storm at sea. The whole city was terrified, thinking that an army was approaching...Even at a distance of a hundred li tiles shook and houses trembled...The disturbance lasted a whole day and night. After order had been restored an inspection was made, and it was found that a hundred men of the guards had been blown to bits, beams and pillars had been cleft asunder or carried away by the force of the explosion to a distance of over ten li. The smooth ground was scooped into craters and trenches more than ten feet deep. Above two hundred families living in the neighborhood were victims of this unexpected disaster.[35]

[Note:One full measurement of a li 里 during the Song Dynasty was approximately 323 meters/1060 feet]

This 14th century military treatise was compiled and edited by Jiao Yu, a confidant of and artillery officer loyal to Zhu Yuanzhang (1328-1398 C.E.). Jiao Yu wrote descriptions of different types of explosive mixtures, firearms, land mines, naval mines, rocket launchers, bombards, cannons, fire lances, fire arrows, and multistage rockets (refer to Huolongjing). The explosive potential of Chinese gunpowder improved as the level of nitrate in formulas had risen to a range of 12% to 91%,[25] with at least 6 different formulas in use that are considered by Needham to have maximum explosive potential for gunpowder.[25] There was also an improvement in the refinement of sulfur from pyrite during the Song Dynasty,[36] which Zhang Yunming has claimed allowed early Chinese saltpeter explosives to rise from simple incendiary use to explosive use in early artillery (for sulfur refinement and manufacturing in the Song period, refer to Economy of the Song Dynasty).[36]

The earliest extant Chinese recipe for black powder by itself, without any additional ingredients, given by Needham, is from 1628, almost four hundred years after Roger Bacon's book (see "Europe," below).[37] It comes from a book called the Wu Pei Chih, which lists all the saltpeter explosive recipes from the 1606 Ping Lu, but includes exactly one new mixture, for "lead bullet gunpowder" (chhien chhung huo yao), composed of 40 oz. of saltpeter, 6 oz. of sulphur, and 6.8 oz. of charcoal. As Needham observes, "The explosive is used here as a charge of black powder."[38]

Islam

Saltpetre combustion technology spread to the Arabs in the 13th century,[39][40] what the Arabs had called "Chinese snow" (thalj al-Sin).[41] Although gunpowder weapons were employed in the Middle East, they were not always met with open acceptance, as there was some antagonism by the Mamluks of Egypt towards early riflemen in their infantry.[42] The same could be said of the Iranian Safavids, who failed to employ the use of firearms at Chaldiran (1514) due to the Qizilbash's prejudice against musket-wielding infantry.[42]

The Turks destroyed the walls of Constantinople in 1453 with 13 enormous cannons with bores upwards of 90 cm, firing a 320 kg projectile a distance of over 1.6 km. Reference was made by João de Barros to a sea battle outside Jiddah, in 1517, between Portuguese and Ottoman vessels. The Muslim force under Salman Reis had "three or four basilisks firing balls of thirty palms in circumference".[43] This was estimated to be a cannon of about 90 inch bore "firing cut stone balls of approximately 1,000 pounds (453 kg)".[43]

Although the cannon and musket were employed by the Ottomans long beforehand, by the 17th century they witnessed how ineffective the traditional cavalry charges were in the face of concentrated musket-fire volleys.[44] In a report given by an Ottoman general in 1602, he confessed that the army was in a distressed position due to the emphasis in European forces for musket-wielding infantry, while the Ottomans relied heavily on cavalry.[44] Thereafter it was suggested that the janisseries, who were already trained and equipped with muskets, become more heavily involved in the imperial army while led by their agha.[44]

Claims of Muslim invention

Ajram (1992) claims that the Chinese only developed saltpeter for use in fireworks and knew of no tactical military use for gunpowder, which was first developed by Muslims, as were fire-arms, and that the first documentation of a cannon was in an Arabic text ca 1300 C.E.

India

Gunpowder arrived in India perhaps as early as the mid-1200s, when the Mongols could have introduced it, but in any event no later than the mid-1300s.[45] It was written in the Tarikh-i Firishta (1606-1607) that the envoy of the Mongol conqueror Hulegu Khan was presented with a dazzling pyrotechnics display upon his arrival in Delhi in 1258 C.E.[46] Firearms known as top-o-tufak also existed in the Vijayanagara Empire of India by as early as 1366 C.E.[46] From then on the employment of gunpowder warfare in India was prevalent, with events such as the siege of Belgaum in 1473 C.E. by the Sultan Muhammad Shah Bahmani.[47]

Claims of Indian invention

Asitesh Bhattacharya cites a number of studies, most from the 19th century, to argue that gunpowder was invented in ancient India.[48]

In 1848, Professor Wilson, speaking to the Asiatic Society of Calcutta (of which he was Director), said,

The question as to the knowledge of gunpowder or any similar explosive substance, by the ancient people of India is one of great historical interest. [O]ur acquaintance with their literature, is as yet, too imperfect to warrant a reply in the negative because we have not met with a positive account of the invention.[49]

Elliot (1875) suggested that saltpetre was possibly present in the explosives used in the fiery devices mentioned in the Mahabharata and Ramayana.[50]

However, doubts about ancient Hindu knowledge of gunpowder were raised as early as 1902 by P.C. Ray.[51] H.W.L. Hime concluded that 'early Indian gunpowder is definitely a fiction'.[51]

And, according to Buchanan (2006:5),

The legendary writings, the mixing of old accounts with new, and the lack of vocabulary to describe the subject, may suggest the absence of any positive evidence of gunpowder making in India in early times despite the presence of the ingredients required.

Europe

The earliest extant written reference to gunpowder in Europe is in Roger Bacon's "De nullitate magiæ" at Oxford in 1234.[9] In Bacon's "De Secretis Operibus Artis et Naturae" in 1248, he states:

We can, with saltpeter and other substances, compose artificially a fire that can be launched over long distances... By only using a very small quantity of this material much light can be created accompanied by a horrible fracas. It is possible with it to destroy a town or an army ... In order to produce this artificial lightning and thunder it is necessary to take saltpeter, sulfur, and Luru Vopo Vir Can Utriet.

The last part is probably some sort of coded anagram for the quantities needed.

In the Opus Maior he describes firecrackers around 1267:

a child’s toy of sound and fire made in various parts of the world with powder of saltpeter, sulphur and charcoal of hazelwood.[52]

This is the earliest recipe given by Joseph Needham for pure black powder from anywhere in the world. [53] This does not necessarily prove that black powder ("gunpowder," following the OED definition) was invented in Europe, however. Roger Bacon does not claim to have invented black powder himself, and his reference to "various parts of the world" implies that black powder was already widespread when he was writing.

In 1326, the earliest known picture of a gun, from anywhere in the world, appeared in a treatise entitled "Of the Majesty, Wisdom and Prudence of Kings," by Walter de Milemete. [54] [55] [56] On February 11 of that same year, the Signoria of Florence appointed two officers to obtain canones de mettallo and ammunition for the town's defense.[57] A reference from 1331 describes an attack mounted by two Germanic knights on Cividale del Friuli, using gunpowder weapons of some sort.[56] The French raiding party that sacked and burned Southampton in 1338 brought with them a ribaudequin and 48 bolts (but only 3 pounds of gunpowder).[56]

The Battle of Crécy in 1346 was one of the first in Europe where cannons were used.[58] Writing shortly after this in 1350, the famous poet Petrarch described cannons on the battlefield "as common and familiar as other kinds of arms."[59]

References to gunnis cum telar (guns with handles) were recorded in 1350, and by 1411 it was recorded that John the Good, Duke of Burgundy, had 4000 handguns stored in his armory.[60] However, musketeers and musket-wielding infantrymen were despised in society by the traditional feudal knights, even until the time of Cervantes (1547-1616 C.E.).[42] At first even Christian authorities made vehement remarks against the use of gunpowder weapons, calling them blasphemous and part of the 'Black Arts'.[61] In an ironic twist, by the mid 14th century, even the army of the Pope would be armed with artillery and gunpowder weapons.[61]

Europe soon surpassed the rest of the world in gunpowder technology, especially during the late 14th century with the development of the process of black powder "corning".[62] Corning involves forcing damp powder through a sieve to form it into granules which harden when dry, preventing the component ingredients of gunpowder from separating over time, thus making it far more reliable and consistent. It also allowed for more powerful and faster ignition, since the spaces between the particles allowed for oxygen necessary for speedy combustion. However, the prevalence of superstitious belief in alchemy and magic commonly led, at least in the early days of firearms, to the adulteration of the mixture with exotic, but of course deleterious products, usually mercury salts, arsenic and amber. [citation needed]

Shot and gunpowder for military purposes were made by skilled military tradesmen, who later were called firemakers, and who also were required to make fireworks for celebrations of victory or peace. During the Renaissance, two European schools of pyrotechnic thought emerged, one in Italy and the other at Nürnberg, Germany. The Italian school of pyrotechnics emphasized elaborate fireworks, and the German school stressed scientific advancement. Both schools added significantly to further development of pyrotechnics, and by the mid-17th century fireworks were used for entertainment on an unprecedented scale in Europe, being popular even at resorts and public gardens.[63]

By 1788, as a result of the reforms for which Lavoisier was mainly responsible, France had become self-sufficient in saltpeter, and its gunpowder had become both the best in Europe and inexpensive.[64]

During the 18th century gunpowder factories became increasingly dependent on mechanical energy.[65]

Gunpowder production in the United Kingdom

Gunpowder production in the United Kingdom appears to have started in the mid 13th century with the aim of supplying The Crown.[66] Records show that gunpowder was being made, in England, in 1346, at the Tower of London; a powder house existed at the Tower in 1461; and in 1515 three King's gunpowder makers worked there.[66] Gunpowder was also being made or stored at other Royal castles, such as Portchester Castle and Edinburgh castle.

By the early fourteenth century, according to N.J.G. Pounds's study The Medieval Castle in England and Wales, many English castles had been deserted. Others were crumbling. Their military significance faded except on the borders. Gunpowder made smaller castles useless.[67]

Henry VIII was short of gunpowder when he invaded France in 1544 and England needed to import gunpowder via the port of Antwerp.[66]

The English Civil War, 1642-1645, led to an expansion of the gunpowder industry, with the repeal of the Royal Patent in August 1641.[66]

Decline of gunpowder production

The introduction of Smokeless powders for military purposes lead to a contraction of the gunpowder industry.

Cessation of gunpowder production in the United Kingdom

The Home Office removed gunpowder from its list of Permitted Explosives; shortly afterwards, on 31 December 1931, Curtis & Harvey's Glynneath gunpowder factory at Pontneddfechan, in Wales, closed down, and it was demolished by fire in 1932.[68]

The last remaining gunpowder mill at the Royal Gunpowder Factory, Waltham Abbey was damaged by a German parachute mine in 1941 and it never reopened.[69] This was followed by the closure of the gunpowder section at the Royal Ordnance Factory, ROF Chorley, the section was closed and demolished at the end of World War II; and ICI Nobel's Roslin gunpowder factory which closed in 1954.[69][70]

This left the sole United Kingdom gunpowder factory at ICI Nobel's Ardeer site in Scotland; it too closed in October 1976.[69] Since then gunpowder has been imported into the United Kingdom. In the late 1970s / early 1980s gunpowder was bought from eastern Europe; particularly from, what were then, the East Germany and Yugoslavia.

Gunpowder production in the United States

Prior to the American Revolutionary War very little gunpowder had been made in the United States; and, as a British Colony, most had been imported from Britain.[11] In October 1777 the British Parliament banned the importation of gunpowder into America.[11] Gunpowder, however, was secretly obtained from France and the Netherlands.[11]

The first domestic supplies of gunpowder were made by E. I. du Pont de Nemours and Company.[11] The company had been founded in 1802 by Eleuthère Irénée du Pont, two years after he and his family left France to escape the French Revolution.[71] They set up a gunpowder mill on the Brandywine at Wilmington, Delaware based on gunpowder machinery bought from France and site plans for a gunpowder mill supplied by the French Government.[71] Starting, initially, by reworking damaged gunpowder and refining saltpetre for the US Government they quickly moved into gunpowder manufacture.[71]

In the United States, saltpetre was worked in the "nitre caves" of Kentucky at the beginning of the 19th century.[72]

Manufacture

Principle of action

Nitrates have the property to release oxygen when heated, and the oxygen is essential to fast burning of carbon and sulfur, therefore resulting in an explosion-like chemical reaction when gunpowder is ignited: carbon burning consumes oxygen and produces heat, which produces even more oxygen etc. The presence of nitrates is crucial to gunpowder composition because the oxygen released by the heat makes burning of carbon and sulfur so much faster that it results in an explosive action, although mild enough not to destroy the barrels of the firearms . The action of gunpowder therefore can be simplistically described as "very fast burning" and is quite mild as opposed to that of brisant explosives, which react so fast that a shock wave is produced which acts more like a hammer-strike than a pressure build-up.

Composition

Black powder is a mixture of saltpeter (potassium nitrate or, less frequently, sodium nitrate), charcoal and sulfur with a ratio (by weight) of approximately 15:3:2 respectively. Modern black powder also typically has a small amount of graphite added to it, to reduce the likelihood of static electricity causing loose black powder to ignite. The ratio has changed over the centuries of its use, and can be altered somewhat depending on the purpose of the powder.

Historically, potassium nitrate was extracted from manure by a process superficially similar to composting. "Nitre beds" took about a year to produce crystallized potassium nitrate. It could also be mined from caves with high concentrations of potassium nitrate, often resulting from the residue from bat dung accumulating over millennia.

Versions of unburnt black powder containing potassium nitrate are not hygroscopic, although versions of black powder containing sodium nitrate tend to be slightly hygroscopic. Because of this, the most common form of black powder containing potassium nitrate can be stored in unsealed powder flasks for very long periods of time, measured in centuries, provided no liquid water is ever introduced, while remaining viable. Similarly, muzzleloaders have been known to fire with a trigger pull many decades after being loaded, after being hung on a wall during an earlier era in a loaded state, provided they are kept dry. In contrast, versions of black powder or gunpowder intended for blasting contain sodium nitrate, and are not known for being as stable over such long periods of time, unless sealed from the moisture in the air.

Residue from burnt black powder, in contrast to unburnt black powder, is hygroscopic, and thus fired black powder residue proves extremely harmful to the steel in guns and gun barrels because it forms corrosive alkalis as moisture is taken into the burnt black powder residue, which typically weigh slightly more than 50% of the unburnt black powder weight.

Sulfur-less gunpowder

The development of smokeless powders, such as Cordite, created the need for a spark-sensitive priming charge, such as gunpowder. However, the sulfur content of gunpowder caused corrosion problems with Cordite Mk I and this led to the introduction of a range of sulfur-less gunpowders, of varying grain sizes.[69] They typically contain 70.5 parts of saltpetre and 29.5 parts of charcoal.[69]

Characteristics and use

Gunpowder is not classified as a high explosive because it has a very slow decomposition rate and therefore a very low brisance. This same property that makes it a poor explosive makes it useful as a propellant — the lack of brisance keeps the black powder from shattering a gun barrel, and directs the energy to propelling the bullet.

Disadvantages of black powder

The main disadvantages of black powder are a relatively low energy density (compared to modern smokeless powders); the extremely large quantities of soot and solid residues left behind; and a dense cloud of white smoke. During the combustion process, less than half of black powder is converted to gas. The rest ends up as a thick layer of soot inside the barrel. In addition to being a nuisance, the residue in the barrel is hygroscopic and an anhydrous caustic substance. When moisture from the air is absorbed, the potassium oxide or sodium oxide turn into hydroxides, which will corrode wrought iron or steel gun barrels. Black powder arms must be well cleaned inside and out after firing to remove the residue. The thick smoke of black powder is also a tactical disadvantage, as it can quickly become so opaque as to impair aiming; it also reveals the shooter's position.

Advantages of black powder

The size of the granule of powder and the confinement determine the burn rate of black powder. Finer grains result in greater surface area, which results in a faster burn. Tight confinement in the barrel causes a column of black powder to explode, which is the desired result. Not seating the bullet firmly against the powder column can result in a harmonic shockwave, which can create a dangerous over-pressure condition and damage the gun barrel. One of the advantages of black powder is that precise loading of the charge is not as vital as with smokeless powder firearms and is carried out using volumetric measures rather than precise weight. However, damage to a gun and its shooter due to overloading is still possible.

Black powder is well suited for blank rounds, signal flares, and rescue line launches.

Additionally, the low brisance of black powder made it useful when blasting monumental stone such as granite and marble. Black powder caused fewer fractures when compared to other explosives, with the result that more of the quarried stone could be used.

Gunpowder can be used to make fireworks by mixing with chemical compounds that produce the desired color.

Notes

- ↑ "gunpowder, n. 1a" The Oxford English Dictionary. 2nd ed. 1989. Oxford English Dictionary Online. Oxford University Press. 4 Apr. 2000 http://dictionary.oed.com/cgi/entry/50100435.

- ↑ "gunpowder." The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. Answers.com 13 Apr. 2007.

- ↑ Lyall, Sarah, "Joseph Needham, China Scholar From Britain, Dies at 94", The New York Times, March 27, 1995.

- ↑ Needham 1986:108

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Needham 1986:109

- ↑ Bowman, John S., ed. (2000), Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture, New York: Columbia University Press, at pp. 104-105 .

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Needham 1986:122 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "needham volume 5 part 7 122" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 8.0 8.1 Kelly 2004:20–22

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 1771, "Gunpowder", Encyclopedia Britannica, London . "frier Bacon, our countryman, mentions the compofition in exprefs terms, in his treatife De nullitate magiæ, publifhed at Oxford, in the year 1248."

- ↑ Needham 1986:108

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Brown 1998

- ↑ Gernet, Jacques (1996), A History of Chinese Civilization (2nd ed.), Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521497817

- ↑ Hall. "Introduction," in Partington (1999), p. xvii

- ↑ Peng 2000

- ↑ Needham & Cullen 1976

- ↑ Liang 2006, Appendix C VII

- ↑ Kelly 2004:3

- ↑ Kelly 2004:4

- ↑ Chase 2003:32

- ↑ Gernet 1996, p. 311 "The discovery originated from the alchemical researches made in the Taoist circles of the T'ang age, but was soon put to military use in the years 904–6. It was a matter at that time of incendiary projectiles called 'flying fires' (fei-huo)."

- ↑ Needham & Cullen 1976, Volume 5, Part 7, 224-225

- ↑ Kelly 2004:15-17

- ↑ Needham & Cullen 1976, Volume 5, Part 7, 82

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 80-84. Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "needham volume 5 part 7 80 81 82" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Needham & Cullen 1976, Volume 5, Part 7, 345

- ↑ Needham & Cullen 1976, Volume 5, Part 7, 347

- ↑ Partington, 240.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 166.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 3, 476.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Needham & Cullen 1976, Volume 5, Part 7, 126

- ↑ Gernet 1996

- ↑ Partington 1960:239-240

- ↑ Needham & Cullen 1976, Volume 5, 264

- ↑ Needham & Cullen 1976, Volume 5, Part 7, 209

- ↑ Needham & Cullen 1976, Volume 5, Part 7, 209-210

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Zhang 1986:489-490

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (2004). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology; The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press, 345. ISBN 0-521-08732-5.

- ↑ Needham, Joseph (2004). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology; The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press, 345. ISBN 0-521-08732-5.

- ↑ Kelly 2004:22 'Around 1240 the Arabs acquired knowledge of saltpeter ("Chinese snow"). They knew of gunpowder soon afterward. They also learned about fireworks ("Chinese flowers") and rockets ("Chinese arrows").'

- ↑ Urbanski 1967, Chapter III: Blackpowder

- ↑ Needham & Cullen 1976, Volume 5, Part 7, 108

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Khan 2004:6

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Guilmartin 1974, Introduction: Jiddah, 1517

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 Khan 2004:5-6

- ↑ Chase, Kenneth (2003). Firearms: A Global History to 1700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 130. ISBN 0521822742.

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Khan 2004:9-10

- ↑ Khan 2004:10

- ↑ Bhattacharya. "Gunpowder and its Applications in Ancient India," in Buchanan (2006)

- ↑ Bhattacharya in Buchanan (2006), p. 43

- ↑ Elliot (1875) Appendix: Note A. On the Early Use of Gunpowder in India. Pages 455 - 482.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 Bhattacharya in Buchanan (2006), p. 49

- ↑ Kelly 2004:25

- ↑ ^ Needham, Joseph (2004). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7: Military Technology; The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge University Press, 108. ISBN 0-521-08732-5

- ↑ Partington, J. R. A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. W. Heffer & Sons, Ltd. Cambridge. 1960. p. ii.

- ↑ Milemete, Walter de. De Notabilitatibus, Sapientis, et Prudentia. 1326. MS. 92, fol. 70 v. Christ Church, Oxford.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 Kelly 2004:29

- ↑ Crosby 2002:120

- ↑ Kelly 2004:19–37

- ↑ Norris 2003:19

- ↑ Norris 2003:8

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Norris 2003:12

- ↑ Kelly 2004:60–61

- ↑ "Fireworks," Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia 2007 © 1997-2007 Microsoft Corporation. All Rights Reserved.

- ↑ Metzner, Paul (1998), Crescendo of the Virtuoso: Spectacle, Skill, and Self-Promotion in Paris during the Age of Revolution, University of California Press

- ↑ Frangsmyr, Tore, J. L. Heilbron, and Robin E. Rider, editors The Quantifying Spirit in the Eighteenth Century. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1990. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft6d5nb455/ p. 292.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 66.2 66.3 Cocroft 2000, "Success to the Black Art!." Chapter 1

- ↑ Ross, Charles. The Custom of the Castle: From Malory to Macbeth. Berkeley: University of California Press, c1997. http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/ft3r29n8qn/ pp. 131-130.

- ↑ Pritchard, Tom; Jack Evans & Sydney Johnson (1985), The Old Gunpowder Factory at Glynneath, Merthyr Tydfil: Merthyr Tydfil & District Naturalists' Society

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 69.3 69.4 Cocroft 2000, "The demise of gunpowder." Chapter 4

- ↑ MacDougall, Ian (2000), "Oh! Ye had to be Careful": Personal Recollections by Roslin Gunpowder Mill Factory Workers, East Linton: Tuckwell Press, ISBN 1-86232-126-4

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 71.2 du Pont, B.G. (1920), E.I. du Pont de Nemours and Company: A History 1802 to 1902, Boston: Houghton Mifflin, ISBN 1-4179-1685-0

- ↑ Calvert, J. B.. Cannons and Gunpowder.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ajram, K. (1992), The Miracle of Islamic Science, Knowledge House, ISBN 0911119434

- Brown, G. I. (1998), The Big Bang: A History of Explosives, Sutton Publishing, ISBN 0-7509-1878-0

- Buchanan, Brenda J., ed. (2006), Gunpowder, Explosives and the State: A Technological History, Aldershot: Ashgate, ISBN 0754652599

- Chase, Kenneth (2003), Firearms: A Global History to 1700, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521822742

- Cocroft, Wayne (2000), Dangerous Energy: The archaeology of gunpowder and military explosives manufacture, Swindon: English Heritage, ISBN 1-85074-718-0

- Crosby, Alfred W. (2002), Throwing Fire: Projectile Technology Through History, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521791588

- Elliot, Henry M. (1875), The History of India: As told by its own Historians: The Muhammadan Period, vol. VI (2006: Elibron Classics Replica ed.), USA: Adamant Media Corporation, ISBN 0543947149 .

- Guilmartin, John Francis (1974), Gunpowder and Galleys: Changing technology and Mediterranean warfare at sea in the sixteenth century, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521202728

- Kelly, Jack (2004), Gunpowder: Alchemy, Bombards, & Pyrotechnics: The History of the Explosive that Changed the World, Basic Books, ISBN 0465037186

- Khan, Iqtidar Alam (2004), Gunpowder and Firearms: Warfare in Medieval India, Oxford University Press

- Liang, Jieming (2006), Chinese Siege Warfare: Mechanical Artillery & Siege Weapons of Antiquity, ISBN 981-05-5380-3

- Needham, Joseph & C. Cullen (1976), Science and Civilisation in China, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521210283

- Needham, Joseph (1986), Science & Civilisation in China, vol. V:7: The Gunpowder Epic, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521303583

- Norris, John (2003), Early Gunpowder Artillery: 1300-1600, Marlborough: The Crowood Press

- Partington, J.R. (1999), A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder, Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, ISBN 0801859549

- Peng, Yoke Ho (2000), Li, Qi and Shu: An Introduction to Science and Civilization in China, Courier Dover Publications, ISBN 0486414450

- Urbanski, Tadeusz (1967), Chemistry and Technology of Explosives, vol. III, New York: Pergamon Press

- Zhang, Yunming (1986), "Ancient Chinese Sulfur Manufacturing Processes", Isis 77 (3): 487–497 .

See also

- Arquebus

- Brown powder

- Cannon

- Elizabethton, Tennessee (American Revolution)

- Firearms

- Firework

- Gonne

- Gunpowder Plot

- Gunpowder warfare

- Guns

- Huolongjing

- Musket

- W231

External links

- Ulrich Bretschler's Gunpowder Chemistry page.

- Gun and Gunpowder

- The Origins of Gunpowder

- Cannons and Gunpowder

- History of Science and Technology in Islam

- Oare Gunpowder Works, Kent, UK

- Royal Gunpowder Mills

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.