Difference between revisions of "Extinction" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (28 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | + | {{Ebapproved}}{{Copyedited}}{{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Status}} | |

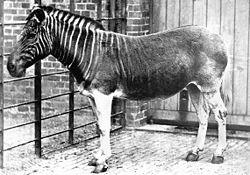

| − | + | [[Image:Quagga_photo.jpg|right|thumb|250px|Quagga from Regent's Park ZOO, London, 1870. The Quagga is one of Africa's most famous extinct animals.]] | |

| − | + | In [[biology]] and [[ecology]], '''extinction''' is the ceasing of existence of a [[species]] or a higher [[taxonomy|taxonomic]] unit (''taxon''), such as a phylum or class. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of that species or group. | |

| − | + | Extinction has occurred throughout the history of living organisms and is usually a natural phenomenon. Mayr (2001) estimates that 99.99% or more of all evolutionary lines have become extinct, and Raup (1991) estimates that 99.9% of all species that have ever existed on earth are now extinct. | |

| − | + | In addition to the extinction of individual species, there have been least five [[Mass extinction|major extinction episodes]] when a large number of ''taxa'' are exterminated in a geologically short period of time. The [[Mass extinction#Permian-Triassic extinction|Permian-Triassic extinction]] alone killed off about 90 percent of marine species and 70 percent of the terrestrial [[vertebrate]] species alive at the time. | |

| − | + | While extinction is an inherent feature of the history of [[life]], there is concern that since the advent of [[human]]s and their expansion over the globe that people are now the primary causal factor in extinctions—causing a sixth mass extinction event. It is apparent that humans have a choice in how they will impact either reduction of [[biodiversity]] or its [[conservation]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | The phenomena of extinction, as evidenced by the discovery of fossils of organisms no longer known to exist on Earth, initially presented a [[religion|religious]]/[[philosophy|philosophical]] problem for those who professed Divine Creation of all of nature’s creatures. (See [[#Extinction: An historical religious conundrum|Extinction:An historical religious conundrum]].) | |

| − | + | [[Endangered species]] are species that are in danger of becoming extinct. Species that are not extinct are termed extant. | |

| − | + | ==Terminology== | |

| + | A species becomes '''extinct''' when the last existing member of that [[species]] dies. Extinction therefore becomes a certainty when no surviving specimens are able to reproduce and create a new generation. A species may become '''functionally extinct''' when only a handful of individuals are surviving, but are unable to reproduce due to health, age, lack of both sexes (in species that [[sexual reproduction|reproduce sexually]]), or other reasons. | ||

| − | + | Descendants may or may not exist for extinct species. ''Daughter species'' that evolve from a parent species carry on most of the parent species' [[genotype|genetic information]], and even though the parent species may become extinct, the daughter species lives on. In other cases, species have produced no new variants, or none that are able to survive the parent species' extinction. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | '''Pseudoextinction''' is a term used by [[paleontologist]]s to refer to a situation whereby the parent species is extinct but daughter species or subspecies are still alive. That is, it is the process whereby a species has evolved into a different species, which has been given a new name; thus, the term really refers to a name change rather than the disappearance of the biological entity (Mayr 2001). However, pseudoextinction is difficult to demonstrate, requiring a strong chain of evidence linking a living species to members of a pre-existing species. For example, it is sometimes claimed that the extinct ''Hyracotherium'', which was an ancient animal similar to the [[horse]], is pseudoextinct, rather than extinct, because there are several [[extant]] species of [[horse]], including [[zebra]]s and [[donkey]]s. However, as [[fossil]] species typically leave no genetic material behind, it is not possible to say whether ''Hyracotherium'' actually evolved into more modern horse species or simply evolved from a common ancestor with modern horses. | |

| − | + | Pseudoextinction, also called phyletic extinction, can sometimes apply to wider ''taxa'' than the species level. For instance, many paleontologists believe the entire superorder [[Dinosaur|Dinosauria]] is pseudoextinct, arguing that the feathered dinosaurs are the ancestors of modern day [[bird]]s. Pseudoextinction for ''taxa'' higher than the genus level is easier for which to provide evidences. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Pinpointing the extinction or pseudoextinction of a species requires a clear definition of that species. The species in question must be identified uniquely from any daughter species, as well as its ancestor species or other closely related populations, if it is to be declared extinct. For further discussion, see [[Species#Definitions of species|definition of species]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | [[ | + | Extinction (or replacement) of species by a daughter species plays a key role in the [[punctuated equilibrium]] hypothesis of [[Stephen Jay Gould]] and Niles Eldredge (1986). |

| − | + | In addition to actual extinction, human attempts to preserve critically endangered species have caused the creation of the conservation status '''extinct in the wild'''. Species listed under this status by the World Conservation Union are not known to have any living specimens in the wild and are maintained only in [[zoo]]s or other artificial environments. Some of these species are functionally extinct. When possible, modern zoological institutions attempt to maintain a viable population for species preservation and possible future reintroduction to the wild through use of carefully planned breeding programs. | |

| − | + | In ecology, ''extinction'' is often used informally to refer to '''local extinction''', in which a species ceases to exist in the chosen area of study, but still exists elsewhere. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Overview and rate== | |

| − | + | The history of extinction in "deep time" prior to [[human]]s comes from the [[fossil]] record. As fossilization is a chance and rare phenomena, it is difficult to gain an accurate picture of the extinction process. | |

| − | + | Extinction was not always an established concept. In the early nineteenth century, [[Georges Cuvier]]'s observations of fossil bones convinced him that they did not originate in extant animals. His work was able to convince many scientists on the reality of extinction. | |

| − | + | The rate at which extinctions occurred prior to humans, independent of mass extinctions, is called the "background" or "normal" rate of extinction. A rule of thumb is that one [[species]] in every million goes extinct per year (Wilson 1992). A typical species becomes extinct within 10 million years of its first appearance, although some species survive virtually unchanged for hundreds of millions of years. | |

| − | + | Just as extinctions reduce [[biodiversity]] by removing species form the earth, new species are created by the process of [[speciation]], thus increasing biodiversity. Biodiversity refers to the diversity of species, as well as the variability of communities and ecosystems and the genetic variability within species (CBC 1999). In the past, species diversity recovered from even mass extinction events, although it took millions of years. It is estimated that ten million years or more have been required to attain prior levels of species diversity after a mass extinction event (CBC 1999). | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Until recently, it had been universally accepted that the extinction of a species meant the end of its time on Earth. However, recent technological advances have encouraged the hypothesis that through the process of [[cloning]], extinct species may be "brought back to life." Proposed targets for cloning include the [[mammoth]] and thylacine (a large carnivorous marsupial native to Australia, known as the Tasmanian Tiger or Tasmanian Wolf). In order for such a program to succeed, a sufficient number of individuals would need to be cloned (in the case of sexually reproducing organisms) to create a viable population size. The cloning of an extinct species has not yet been attempted, due to technological limitations, as well as [[bioethics|ethical]] and [[philosophy|philosophical]] questions. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | There | + | ==Causes== |

| + | There are a variety of causes that can contribute directly or indirectly to the extinction of a species or group of species. In general, species become extinct when are no longer able to survive in changing conditions or against superior competition. Any species that is unable to survive or [[reproduction|reproduce]] in its environment, and unable to move to a new environment where it can do so, dies out and becomes extinct. | ||

| − | + | Extinction of a species may come suddenly when an otherwise healthy species is wiped out completely, as when toxic pollution renders its entire habitat unlivable; or may occur gradually over thousands or millions of years, such as when a species gradually loses out competition for food to newer, better adapted competitors. It has been estimated that around three species of birds die out every year due to competition. | |

| − | == | + | ===Genetic and demographic causes=== |

| − | + | Genetic and demographic phenomena affect the extinction of species. Regarding the possibility of extinction, small populations that represent an entire species are much more vulnerable to these types of effects. | |

| − | + | [[Natural selection]] acts to propagate beneficial genetic traits and eliminate weaknesses. However, it is sometimes possible for a deleterious mutation to be spread throughout a population through the effect of genetic drift. | |

| − | + | A diverse or "deep" [[gene pool]] gives a population a higher chance of surviving an adverse change in conditions. Effects that cause or reward a loss in genetic diversity can increase the chances of extinction of a species. Population bottlenecks can dramatically reduce genetic diversity by severely limiting the number of reproducing individuals and make inbreeding more frequent. The [[founder effect]] can cause rapid, individual-based speciation and is the most dramatic example of a population bottleneck. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Habitat degradation=== | |

| + | The degradation of a species' habitat may alter the fitness landscape to such an extent that the species is no longer able to survive and becomes extinct. This may occur by direct effects, such as the environment becoming toxic, or indirectly, by limiting a species' ability to compete effectively for diminished resources or against new competitor species. Major climate changes, such as ice ages or asteroid impacts, and subsequent habitat degradation have been cited as major factors in many major extinctions in the past. | ||

| − | + | Habitat degradation through toxicity can kill off a species very rapidly, by killing all living members through contamination or sterilizing them. It can also occur over longer periods at lower toxicity levels by affecting life span, reproductive capacity, or competitiveness. | |

| − | + | Habitat degradation can also take the form of a physical destruction of niche habitats. The widespread destruction of tropical [[rainforest]]s and replacement with open pastureland is widely cited as an example of this; elimination of the dense forest eliminated the infrastructure needed by many species to survive. For example, a [[fern]] that depends on dense shade to make a suitable environment can no longer survive with no forest to house it. | |

| − | + | Vital resources, including [[water]] and food, can also be limited during habitat degradation, causing some species to become extinct. | |

| − | + | ===Predation, competition, and disease=== | |

| − | + | Introduction of new competitor species are also a factor in extinction and often accompany habitat degradation, as well. Sometimes these new competitors are predators and directly affect prey species, while at other times they may merely out-compete vulnerable species for limited resources. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Humans have been transporting [[animal]]s and [[plant]]s from one part of the world to another for thousands of years, sometimes deliberately (e.g., [[livestock]] released by sailors onto islands as a source of food) and sometimes accidentally (e.g., [[rat]]s escaping from boats). In most cases, such introductions are unsuccessful, but when they do become established as an invasive alien species, the consequences can be catastrophic. Invasive alien species can affect endemic (native) species directly by eating them, competing with them, and introducing [[pathogen]]s or [[parasite]]s that sicken or kill them or, indirectly, by destroying or degrading their habitat. | |

| − | + | ==Mass extinctions== | |

| + | {{main|Mass extinction}} | ||

| − | + | There have been at least five '''[[mass extinction]]s''' in the history of life prior to humans, and many smaller extinction events. The most recent of these, the K-T extinction, 65 million years ago at the end of the [[Cretaceous]] period, is best known for having wiped out the non-[[avian]] dinosaurs, among many other species. | |

| − | The | + | ==Extinction: An historical religious conundrum== |

| + | The phenomena of extinction, as evidenced by the discovery of fossils of organisms no longer known to exist on Earth, challenged at least three of the [[religion|religious]]/[[philosophy|philosophical]] premises of those many who professed Divine Creation: | ||

| + | *God is perfect and He made a perfect creation. Therefore all of His created organisms are needed for that full perfection to be manifested. Why, then, would He allow any of his created organisms to become extinct? | ||

| + | *God is all-loving and all-powerful. Surely, then, He would not permit any of His created organisms to become extinct. | ||

| + | *All created beings from the lowliest to humans and angels and God are connected in a continuous [[Great_Chain_of_Being|Great Chain of Being.]] If one organism were to become extinct, that would become a break in the chain. | ||

| − | + | Because of these concerns, many scientists in the 17th and 18th century denied the reality of extinction, believing that the animals depicted from the fossils were still living in remote regions. Dr. Thomas Molyneux, the naturalist who first described the extinct Irish Elk, professed in 1697, when describing the remains of this deer: "''no real species of living creatures is so utterly extinct, as to be lost entirely out of the World, since it was first created, is the opinion of many naturalists; and 'tis grounded on so good a principle of Providence taking care in general of all its animal productions, that it deserves our assent"'' (McSweegan 2001, Berkeley 2006). | |

| − | + | Today, extinction as a fact is accepted by almost all religious faiths, and views of God's nature and the relation between God and creation have been modified accordingly. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ==Humans and extinction== | |

| − | + | [[Human]]s can cause extinction of a species through overharvesting, [[pollution]], destruction of habitat, introduction of new predators and food [[competitors]], and other influences, including the spread of [[disease]]s (that are not necessarily carried by humans, but associated animals, such as [[rat]]s and [[bird]]s). The elimination of large [[mammal]]s, such as the [[mammoth]]s, may have wider repercussions on other flora and fauna. | |

| − | + | Some consider that humans are now playing a role in extinction "that previously was reserved for asteroids, climate changes, and other global-scale phenomena" (CBC 1999). According to the World Conservation Union, 784 extinctions have been recorded since the year 1500, the arbitrary date selected to define "modern" extinctions, with many more likely to have gone unnoticed. Most of these modern extinctions can be attributed directly or indirectly to human effects. | |

| − | + | According to a 1998 survey of four hundred biologists conducted by the American Museum of Natural History, nearly 70 percent of biologists believe that we are currently in the early stages of a human-caused mass extinction, known as the Holocene extinction event or "Sixth Extinction." Some scientists speculate that there soon may be a loss of species 1,000 times the normal or background rate of extinction (CBC 1999). E. O. Wilson (1992) has estimated that the loss of species in moist tropical forests is approximately 27,000 species per year, based largely on human impacts. | |

| − | + | However, many non-governmental organizations (NGOs), governmental agencies, and intergovernmental bodies are working to conserve biodiversity. Governments sometimes see the loss of native species as a loss to ecotourism, and can enact laws with severe punishment against the trade in native species in an effort to prevent extinction in the wild. Some endangered species also are considered symbolically important and receive special attention. | |

| − | + | Olivia Judson is one of few modern scientists to have advocated the deliberate extinction of any species. Her controversial 2003 ''New York Times'' article advocates "specicide" of 30 [[mosquito]] species through the introduction of recessive "knockout genes." Her defense of such a measure rests on: | |

| − | + | * Anopheles [[mosquito]]s and the Aedes mosquito represent only 30 species; eradicating these would save at least one million human lives per annum at a cost of reducing the genetic diversity of the family [[Culicidae]] by only 1%. | |

| − | + | * She writes that since species go extinct "all the time" the disappearance of a few more will not destroy the [[ecosystem]]: "We're not left with a wasteland every time a species vanishes. Removing one species sometimes causes shifts in the populations of other species—but different need not mean worse." | |

| − | + | * Anti-[[malaria]]l and mosquito control programs offer little realistic hope to the 300 million people in developing nations who will be infected with acute illnesses in a given year; although trials are ongoing, she writes that if they fail: "We should consider the ultimate swatting." | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * [[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | * | + | * Center for Biodiversity and Conservation (CBC), American Museum of Natural History. 1999. ''Humans and Other Catastophes: Perspectives on Extinction''. New York, NY: American Museum of Natural History. |

| − | + | * Eldredge, N. 1986. ''Time Frames: Rethinking of Darwinian Evolution and the Theory of Punctuated Equilibria''. Heinemann. ISBN 0434226106 | |

| − | + | * Eldredge, N. 1998. ''Life in the Balance: Humanity and the Biodiversity Crisis''. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. | |

| − | + | * Leakey, R., and R. Lewin. 1995. ''The Sixth Extinction: Patterns of Life and the Future of Humankind''. New York, NY: Doubleday. | |

| − | + | * McSweegan, E. 2001. Books in Brief: Nonfiction; Too Late the Potoroo." ''The New York Times'' November 25, 2001. | |

| − | + | * Raup, David M. 1991. ''Extinction: Bad Genes or Bad Luck?'' New York: W.W. Norton & Co. | |

| − | + | * University of California Museum of Paleontology. 2005. [[http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/mammal/artio/irishelk.html The Case of the Irish Elk]] (accessed November 30, 2006). | |

| − | + | * Wilson, E. O. 1992. ''The Diversity of Life''. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. | |

| − | + | * Wilson, E. O. 2002. ''The Future of Life''. Little, Brown & Co. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{ | + | {{credit2|Extinction|52451719|Pseudoextinction|39951320}} |

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

| + | [[Category:Evolution]] | ||

Latest revision as of 06:16, 13 September 2023

In biology and ecology, extinction is the ceasing of existence of a species or a higher taxonomic unit (taxon), such as a phylum or class. The moment of extinction is generally considered to be the death of the last individual of that species or group.

Extinction has occurred throughout the history of living organisms and is usually a natural phenomenon. Mayr (2001) estimates that 99.99% or more of all evolutionary lines have become extinct, and Raup (1991) estimates that 99.9% of all species that have ever existed on earth are now extinct.

In addition to the extinction of individual species, there have been least five major extinction episodes when a large number of taxa are exterminated in a geologically short period of time. The Permian-Triassic extinction alone killed off about 90 percent of marine species and 70 percent of the terrestrial vertebrate species alive at the time.

While extinction is an inherent feature of the history of life, there is concern that since the advent of humans and their expansion over the globe that people are now the primary causal factor in extinctions—causing a sixth mass extinction event. It is apparent that humans have a choice in how they will impact either reduction of biodiversity or its conservation.

The phenomena of extinction, as evidenced by the discovery of fossils of organisms no longer known to exist on Earth, initially presented a religious/philosophical problem for those who professed Divine Creation of all of nature’s creatures. (See Extinction:An historical religious conundrum.)

Endangered species are species that are in danger of becoming extinct. Species that are not extinct are termed extant.

Terminology

A species becomes extinct when the last existing member of that species dies. Extinction therefore becomes a certainty when no surviving specimens are able to reproduce and create a new generation. A species may become functionally extinct when only a handful of individuals are surviving, but are unable to reproduce due to health, age, lack of both sexes (in species that reproduce sexually), or other reasons.

Descendants may or may not exist for extinct species. Daughter species that evolve from a parent species carry on most of the parent species' genetic information, and even though the parent species may become extinct, the daughter species lives on. In other cases, species have produced no new variants, or none that are able to survive the parent species' extinction.

Pseudoextinction is a term used by paleontologists to refer to a situation whereby the parent species is extinct but daughter species or subspecies are still alive. That is, it is the process whereby a species has evolved into a different species, which has been given a new name; thus, the term really refers to a name change rather than the disappearance of the biological entity (Mayr 2001). However, pseudoextinction is difficult to demonstrate, requiring a strong chain of evidence linking a living species to members of a pre-existing species. For example, it is sometimes claimed that the extinct Hyracotherium, which was an ancient animal similar to the horse, is pseudoextinct, rather than extinct, because there are several extant species of horse, including zebras and donkeys. However, as fossil species typically leave no genetic material behind, it is not possible to say whether Hyracotherium actually evolved into more modern horse species or simply evolved from a common ancestor with modern horses.

Pseudoextinction, also called phyletic extinction, can sometimes apply to wider taxa than the species level. For instance, many paleontologists believe the entire superorder Dinosauria is pseudoextinct, arguing that the feathered dinosaurs are the ancestors of modern day birds. Pseudoextinction for taxa higher than the genus level is easier for which to provide evidences.

Pinpointing the extinction or pseudoextinction of a species requires a clear definition of that species. The species in question must be identified uniquely from any daughter species, as well as its ancestor species or other closely related populations, if it is to be declared extinct. For further discussion, see definition of species.

Extinction (or replacement) of species by a daughter species plays a key role in the punctuated equilibrium hypothesis of Stephen Jay Gould and Niles Eldredge (1986).

In addition to actual extinction, human attempts to preserve critically endangered species have caused the creation of the conservation status extinct in the wild. Species listed under this status by the World Conservation Union are not known to have any living specimens in the wild and are maintained only in zoos or other artificial environments. Some of these species are functionally extinct. When possible, modern zoological institutions attempt to maintain a viable population for species preservation and possible future reintroduction to the wild through use of carefully planned breeding programs.

In ecology, extinction is often used informally to refer to local extinction, in which a species ceases to exist in the chosen area of study, but still exists elsewhere.

Overview and rate

The history of extinction in "deep time" prior to humans comes from the fossil record. As fossilization is a chance and rare phenomena, it is difficult to gain an accurate picture of the extinction process.

Extinction was not always an established concept. In the early nineteenth century, Georges Cuvier's observations of fossil bones convinced him that they did not originate in extant animals. His work was able to convince many scientists on the reality of extinction.

The rate at which extinctions occurred prior to humans, independent of mass extinctions, is called the "background" or "normal" rate of extinction. A rule of thumb is that one species in every million goes extinct per year (Wilson 1992). A typical species becomes extinct within 10 million years of its first appearance, although some species survive virtually unchanged for hundreds of millions of years.

Just as extinctions reduce biodiversity by removing species form the earth, new species are created by the process of speciation, thus increasing biodiversity. Biodiversity refers to the diversity of species, as well as the variability of communities and ecosystems and the genetic variability within species (CBC 1999). In the past, species diversity recovered from even mass extinction events, although it took millions of years. It is estimated that ten million years or more have been required to attain prior levels of species diversity after a mass extinction event (CBC 1999).

Until recently, it had been universally accepted that the extinction of a species meant the end of its time on Earth. However, recent technological advances have encouraged the hypothesis that through the process of cloning, extinct species may be "brought back to life." Proposed targets for cloning include the mammoth and thylacine (a large carnivorous marsupial native to Australia, known as the Tasmanian Tiger or Tasmanian Wolf). In order for such a program to succeed, a sufficient number of individuals would need to be cloned (in the case of sexually reproducing organisms) to create a viable population size. The cloning of an extinct species has not yet been attempted, due to technological limitations, as well as ethical and philosophical questions.

Causes

There are a variety of causes that can contribute directly or indirectly to the extinction of a species or group of species. In general, species become extinct when are no longer able to survive in changing conditions or against superior competition. Any species that is unable to survive or reproduce in its environment, and unable to move to a new environment where it can do so, dies out and becomes extinct.

Extinction of a species may come suddenly when an otherwise healthy species is wiped out completely, as when toxic pollution renders its entire habitat unlivable; or may occur gradually over thousands or millions of years, such as when a species gradually loses out competition for food to newer, better adapted competitors. It has been estimated that around three species of birds die out every year due to competition.

Genetic and demographic causes

Genetic and demographic phenomena affect the extinction of species. Regarding the possibility of extinction, small populations that represent an entire species are much more vulnerable to these types of effects.

Natural selection acts to propagate beneficial genetic traits and eliminate weaknesses. However, it is sometimes possible for a deleterious mutation to be spread throughout a population through the effect of genetic drift.

A diverse or "deep" gene pool gives a population a higher chance of surviving an adverse change in conditions. Effects that cause or reward a loss in genetic diversity can increase the chances of extinction of a species. Population bottlenecks can dramatically reduce genetic diversity by severely limiting the number of reproducing individuals and make inbreeding more frequent. The founder effect can cause rapid, individual-based speciation and is the most dramatic example of a population bottleneck.

Habitat degradation

The degradation of a species' habitat may alter the fitness landscape to such an extent that the species is no longer able to survive and becomes extinct. This may occur by direct effects, such as the environment becoming toxic, or indirectly, by limiting a species' ability to compete effectively for diminished resources or against new competitor species. Major climate changes, such as ice ages or asteroid impacts, and subsequent habitat degradation have been cited as major factors in many major extinctions in the past.

Habitat degradation through toxicity can kill off a species very rapidly, by killing all living members through contamination or sterilizing them. It can also occur over longer periods at lower toxicity levels by affecting life span, reproductive capacity, or competitiveness.

Habitat degradation can also take the form of a physical destruction of niche habitats. The widespread destruction of tropical rainforests and replacement with open pastureland is widely cited as an example of this; elimination of the dense forest eliminated the infrastructure needed by many species to survive. For example, a fern that depends on dense shade to make a suitable environment can no longer survive with no forest to house it.

Vital resources, including water and food, can also be limited during habitat degradation, causing some species to become extinct.

Predation, competition, and disease

Introduction of new competitor species are also a factor in extinction and often accompany habitat degradation, as well. Sometimes these new competitors are predators and directly affect prey species, while at other times they may merely out-compete vulnerable species for limited resources.

Humans have been transporting animals and plants from one part of the world to another for thousands of years, sometimes deliberately (e.g., livestock released by sailors onto islands as a source of food) and sometimes accidentally (e.g., rats escaping from boats). In most cases, such introductions are unsuccessful, but when they do become established as an invasive alien species, the consequences can be catastrophic. Invasive alien species can affect endemic (native) species directly by eating them, competing with them, and introducing pathogens or parasites that sicken or kill them or, indirectly, by destroying or degrading their habitat.

Mass extinctions

There have been at least five mass extinctions in the history of life prior to humans, and many smaller extinction events. The most recent of these, the K-T extinction, 65 million years ago at the end of the Cretaceous period, is best known for having wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs, among many other species.

Extinction: An historical religious conundrum

The phenomena of extinction, as evidenced by the discovery of fossils of organisms no longer known to exist on Earth, challenged at least three of the religious/philosophical premises of those many who professed Divine Creation:

- God is perfect and He made a perfect creation. Therefore all of His created organisms are needed for that full perfection to be manifested. Why, then, would He allow any of his created organisms to become extinct?

- God is all-loving and all-powerful. Surely, then, He would not permit any of His created organisms to become extinct.

- All created beings from the lowliest to humans and angels and God are connected in a continuous Great Chain of Being. If one organism were to become extinct, that would become a break in the chain.

Because of these concerns, many scientists in the 17th and 18th century denied the reality of extinction, believing that the animals depicted from the fossils were still living in remote regions. Dr. Thomas Molyneux, the naturalist who first described the extinct Irish Elk, professed in 1697, when describing the remains of this deer: "no real species of living creatures is so utterly extinct, as to be lost entirely out of the World, since it was first created, is the opinion of many naturalists; and 'tis grounded on so good a principle of Providence taking care in general of all its animal productions, that it deserves our assent" (McSweegan 2001, Berkeley 2006).

Today, extinction as a fact is accepted by almost all religious faiths, and views of God's nature and the relation between God and creation have been modified accordingly.

Humans and extinction

Humans can cause extinction of a species through overharvesting, pollution, destruction of habitat, introduction of new predators and food competitors, and other influences, including the spread of diseases (that are not necessarily carried by humans, but associated animals, such as rats and birds). The elimination of large mammals, such as the mammoths, may have wider repercussions on other flora and fauna.

Some consider that humans are now playing a role in extinction "that previously was reserved for asteroids, climate changes, and other global-scale phenomena" (CBC 1999). According to the World Conservation Union, 784 extinctions have been recorded since the year 1500, the arbitrary date selected to define "modern" extinctions, with many more likely to have gone unnoticed. Most of these modern extinctions can be attributed directly or indirectly to human effects.

According to a 1998 survey of four hundred biologists conducted by the American Museum of Natural History, nearly 70 percent of biologists believe that we are currently in the early stages of a human-caused mass extinction, known as the Holocene extinction event or "Sixth Extinction." Some scientists speculate that there soon may be a loss of species 1,000 times the normal or background rate of extinction (CBC 1999). E. O. Wilson (1992) has estimated that the loss of species in moist tropical forests is approximately 27,000 species per year, based largely on human impacts.

However, many non-governmental organizations (NGOs), governmental agencies, and intergovernmental bodies are working to conserve biodiversity. Governments sometimes see the loss of native species as a loss to ecotourism, and can enact laws with severe punishment against the trade in native species in an effort to prevent extinction in the wild. Some endangered species also are considered symbolically important and receive special attention.

Olivia Judson is one of few modern scientists to have advocated the deliberate extinction of any species. Her controversial 2003 New York Times article advocates "specicide" of 30 mosquito species through the introduction of recessive "knockout genes." Her defense of such a measure rests on:

- Anopheles mosquitos and the Aedes mosquito represent only 30 species; eradicating these would save at least one million human lives per annum at a cost of reducing the genetic diversity of the family Culicidae by only 1%.

- She writes that since species go extinct "all the time" the disappearance of a few more will not destroy the ecosystem: "We're not left with a wasteland every time a species vanishes. Removing one species sometimes causes shifts in the populations of other species—but different need not mean worse."

- Anti-malarial and mosquito control programs offer little realistic hope to the 300 million people in developing nations who will be infected with acute illnesses in a given year; although trials are ongoing, she writes that if they fail: "We should consider the ultimate swatting."

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Center for Biodiversity and Conservation (CBC), American Museum of Natural History. 1999. Humans and Other Catastophes: Perspectives on Extinction. New York, NY: American Museum of Natural History.

- Eldredge, N. 1986. Time Frames: Rethinking of Darwinian Evolution and the Theory of Punctuated Equilibria. Heinemann. ISBN 0434226106

- Eldredge, N. 1998. Life in the Balance: Humanity and the Biodiversity Crisis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Leakey, R., and R. Lewin. 1995. The Sixth Extinction: Patterns of Life and the Future of Humankind. New York, NY: Doubleday.

- McSweegan, E. 2001. Books in Brief: Nonfiction; Too Late the Potoroo." The New York Times November 25, 2001.

- Raup, David M. 1991. Extinction: Bad Genes or Bad Luck? New York: W.W. Norton & Co.

- University of California Museum of Paleontology. 2005. [The Case of the Irish Elk] (accessed November 30, 2006).

- Wilson, E. O. 1992. The Diversity of Life. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wilson, E. O. 2002. The Future of Life. Little, Brown & Co.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.