Difference between revisions of "Ethology" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (27 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebapproved}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | + | [[Image:V31-d-Graugans.JPG|right|thumb|250px|The egg-rolling behavior of the greylag goose is a widely cited example of a ''fixed-action pattern,'' one of the key concepts used by ethologists to explain animal behavior.]] | |

| − | '''Ethology''' is a branch of [[zoology]] concerned with the study of [[animal]] [[behavior]]. Ethologists | + | '''Ethology''' is a branch of [[zoology]] concerned with the study of [[animal]] [[behavior]]. Ethologists take a comparative approach, studying behaviors ranging from kinship, cooperation, and parental investment, to conflict, sexual selection, and aggression across a variety of [[species]]. Today ''ethology'' as a disciplinary label has largely been replaced by [[behavioral ecology]] and [[evolutionary psychology]]. These rapidly growing fields tend to place greater emphasis on social relationships rather than on the individual animal; however, they retain ethology’s tradition of fieldwork and its grounding in evolutionary theory. |

| − | + | The study of animal behavior touches upon the fact that people receive joy from [[nature]] and also typically see themselves in a special role as stewards of creation. Behavior is one aspect of the vast diversity of nature that enhances human enjoyment. People are fascinated with the many behaviors of animals, whether the communication "dance" of [[honeybee]]s, or the hunting behavior of the big [[cat]]s, or the altruistic behavior of a [[dolphin]]. In addition, humans generally see themselves with the responsibility to love and care for nature. | |

| − | + | The study of animal behavior also helps people to understand more about themselves. From an evolutionary point of view, organisms of diverse lineages are related through the process of [[evolution#theory of descent with modification|descent with modification]]. From a religious point of view, human also stand as “microcosms of nature" (Burns 2006). Thus, the understanding of animals helps to better understand ourselves. | |

| − | + | Ethologists engage in hypothesis-driven experimental investigation, often in the field. This combination of lab work with field study reflects an important conceptual underpinning of the discipline: behavior is assumed to be ''adaptive''; in other words, something that makes it better suited in its environment and consequently improves its chances of survival and reproductive success. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Ethology emerged as a discrete discipline in the 1920s, through the efforts of [[Konrad Lorenz]], [[Karl von Frisch]], and [[Niko Tinbergen]], who were jointly awarded the 1973 [[Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine]] for their contributions to the study of behavior. They were in turn influenced by the foundational work of, among others, ornithologists [[Oskar Heinroth]] and [[Julian Huxley]] and the American [[myrmecologist]] (study of ants) [[William Morton Wheeler]], who popularized the term ''ethology'' in a seminal 1902 paper. | ||

| − | + | ==Important concepts== | |

| + | One of the key ideas of classical ethology is the concept of [[fixed action pattern]]s (FAPs). FAPs are stereotyped behaviors that occur in a predictable, inflexible sequence in response to an identifiable stimulus from the environment. | ||

| − | + | [[Image:Larus_Dominicanus.jpg|right|thumb|250px|[[Kelp Gull]] chicks peck at a red spot on their mother's beak to stimulate the regurgitating reflex, another example of a fixed action pattern.]] | |

| + | For example, at the sight of a displaced [[Egg (biology)|egg]] near the nest, the greylag goose ''(Anser anser)'' will roll the egg back to the others with its beak. If the egg is removed, the animal continues to engage in egg-rolling behavior, pulling its head back as if an imaginary egg is still being maneuvered by the underside of its beak. It will also attempt to move other egg-shaped objects, such as a golf ball, doorknob, or even an egg too large to have been laid by the goose itself (Tinbergen 1991). | ||

| − | + | Another important concept is ''filial imprinting,'' a form of learning that occurs in young animals, usually during a critical, formative period of their lives. During imprinting, a young animal learns to direct some of its social responses to a parent or sibling. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Despite its valuable contributions to the study of animal behavior, classical ethology also spawned problematic general theories that viewed even complex behaviors as genetically hardwired (i.e., ''innate'' or ''instinctive''). Models of behavior have since been revised to account for more flexible decision-making processes (Barnard 2003). | |

==Methodology== | ==Methodology== | ||

===Tinbergen's four questions for ethologists=== | ===Tinbergen's four questions for ethologists=== | ||

| − | + | The practice of ethological investigation is rooted in hypothesis-driven experimentation. [[Konrad Lorenz|Lorenz]]'s collaborator, [[Niko Tinbergen]], argued that ethologists should consider the following categories when attempting to formulate a hypothesis that explains any instance of behavior: | |

| + | |||

| + | * Function: How does the behavior impact the animal's chance of survival and reproduction? | ||

| + | * Mechanism: What are the stimuli that elicit the response? How has the response been modified by recent learning? | ||

| + | * Development: How does the behavior change with age? What early experiences are necessary for the behavior to be demonstrated? | ||

| + | * Evolutionary history: How does the behavior compare with similar behavior in related species? How might the behavior have arisen through the evolutionary development of the [[species]], [[genus]], or group? | ||

| − | + | The four questions are meant to be complementary, revealing various facets of the motives underlying a given behavior. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

===Using fieldwork to test hypotheses=== | ===Using fieldwork to test hypotheses=== | ||

| − | + | As an example of how an ethologist might approach a question about animal behavior, consider the study of [[hearing]] in an [[echolocating]] [[bat]]. A species of bat may use frequency chirps to probe the environment while in flight. A traditional neuroscientific study of the [[auditory system]] of the bat would involve [[Anesthesia|anesthetizing]] it, performing a [[craniotomy]] to insert [[Electrophysiology#Electrophysiology_-_the_techniques|recording electrodes]] in its [[brain]], and then recording [[action potential|neural responses]] to pure [[pitch (music)|tone]] [[stimulus (physiology)|stimuli]] played from loudspeakers. In contrast, an ideal ethological study would attempt to replicate the natural conditions of the animal as closely as possible. It would involve recording from the animal’s brain while it is awake, producing its natural calls while performing a behavior such as insect capture. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Key principles and concepts== | ==Key principles and concepts== | ||

===Behaviors are adaptive responses to natural selection=== | ===Behaviors are adaptive responses to natural selection=== | ||

| − | Because ethology is understood as a branch of biology, ethologists have been particularly concerned with the [[evolution]] of behavior and the understanding of behavior in terms of the theory of | + | Because ethology is understood as a branch of biology, ethologists have been particularly concerned with the [[evolution]] of behavior and the understanding of behavior in terms of the [[evolution#theory of natural selection|theory of natural selection]]. In one sense, the first modern ethologist was [[Charles Darwin]], whose book ''The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals'' (1872) has influenced many ethologists. (Darwin’s protégé [[George Romanes]] became one of the founders of comparative psychology, positing a similarity of cognitive processes and mechanisms between animals and humans.) |

| + | |||

| + | Note, however, that this concept is necessarily speculative. Behaviors are not found as [[fossil]]s and cannot be traced through the geological strata. And concrete evidence for the theory of modification by natural selection is limited to [[microevolution]]—that is, evolution at or below the level of species. The evidence that [[natural selection]] directs changes on the [[macroevolution]]ary level necessarily involves extrapolation from these evidences on the microevolutionary level. Thus, although scientists frequently allude to a particular behavior having evolved by natural selection in response to a particular environment, this involves speculation as opposed to concrete evidence. | ||

===Animals use fixed action patterns in communication=== | ===Animals use fixed action patterns in communication=== | ||

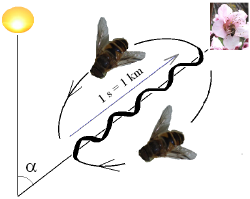

| − | [[Image:Bee dance.png|thumb| | + | [[Image:Bee dance.png|thumb|right|250px|The [[honeybee]]'s figure-eight dance is a fixed-action pattern that communicates information to other members of the group: the angle from the sun indicates the direction of a food source; the duration signifies its distance.]] |

| + | |||

| + | As mentioned above, a ''fixed action pattern (FAP)'' is an [[instinct]]ive [[behavior]]al sequence produced by a [[biological neural network|neural network]] known as the ''innate releasing mechanism'' in response to an external sensory stimulus called the ''sign stimulus'' or ''releaser.'' Once identified by ethologists, FAPs can be compared across species, allowing them to contrast similarities and differences in behavior with similarities and differences in form ([[morphology (biology)|morphology]]). | ||

| + | |||

| + | An example of how FAPs work in animal communication is the classic investigation by Austrian ethologist [[Karl von Frisch]] of the so-called "dance language" underlying [[honeybee#communication|bee communication]]. The dance is a mechanism for successful foragers to recruit members of the colony to new sources of [[nectar]] or [[pollen]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Imprinting is a type of learning behavior=== | ||

| + | ''Imprinting'' describes any kind of phase-sensitive [[learning]] (i.e., learning that occurs at a particular age or life stage) during which an animal learns the characteristics of some stimulus, which is therefore said to be "imprinted" onto the subject. | ||

| − | + | The best known form of imprinting is ''filial imprinting,'' in which a young animal learns the characteristics of its parent. [[Konrad Lorenz|Lorenz]] observed that the young of [[waterfowl]] such as [[goose|geese]] spontaneously followed their mothers from almost the first day after they were hatched. Lorenz demonstrated how incubator-hatched geese would imprint on the first suitable moving stimulus they saw within what he called a [[critical period]] of about 36 hours shortly after hatching. Most famously, the goslings would imprint on Lorenz himself (more specifically, on his wading boots). | |

| − | + | ''Sexual imprinting,'' which occurs at a later stage of development, is the process by which a young animal learns the characteristics of a desirable mate. For example, male [[zebra finch]]es appear to prefer mates with the appearance of the female bird that rears them, rather than mates of their own type (Immelmann 1972). ''Reverse'' sexual imprinting has also observed: when two individuals live in close domestic proximity during their early years, both are desensitized to later sexual attraction. This phenomenon, known as the ''[[Edvard Westermarck|Westermarck effect]],'' has probably evolved to suppress [[inbreeding]]. | |

| − | == | + | ==Relation to comparative psychology== |

| − | [[ | + | In order to summarize the defining features of ethology, it might be helpful to compare classical ethology to early work in [[comparative psychology]], an alternative approach to the study of animal behavior that also emerged in the early 20th century. The rivalry between these two fields stemmed in part from disciplinary politics: ethology, which had developed in Europe, failed to gain a strong foothold in [[North America]], where comparative psychology was dominant. |

| − | + | Broadly speaking, comparative psychology studies general processes, while ethology focuses on adaptive specialization. The two approaches are complementary rather than competitive, but they do lead to different perspectives and sometimes to conflicts of opinion about matters of substance: | |

| − | + | *Comparative psychology construes its study as a branch of [[psychology]] rather than as an outgrowth of [[biology]]. Thus, where comparative psychology sees the study of animal behavior in the context of what is known about human psychology, ethology situates animal behavior in the context of what is known about animal [[anatomy]], [[physiology]], [[neurobiology]], and [[phylogenetic]] history. | |

| + | *Comparative psychologists are interested more in similarities than differences in behavior; they are seeking general laws of behavior, especially relating to development, which can then be applied to all animal species, including humans. Hence, early comparative psychologists concentrated on gaining extensive knowledge of the behavior of a few [[species]], while ethologists were more interested in gaining knowledge of behavior in a wide range of species in order to be able to make principled comparisons across [[taxonomy|taxonomic]] groups. | ||

| + | *Comparative psychologists focused primarily on lab experiments involving a handful of species, mainly [[rat]]s and [[pigeon]]s, whereas ethologists concentrated on behavior in natural situations. | ||

| − | + | Since the 1970s, however, animal behavior has become an integrated discipline, with comparative psychologists and ethological animal behaviorists working on similar problems and publishing side by side in the same journals. | |

==Recent developments in the field== | ==Recent developments in the field== | ||

| − | In | + | In 1970, the [[England|English]] ethologist John H. Crook published an important paper in which he distinguished ''comparative ethology'' from ''social ethology''. He argued that the ethological studies published to date had focused on the former approach—looking at animals as individuals—whereas in the future ethologists would need to concentrate on the social behavior of animal groups. |

| − | Since the appearance of [[E. O. Wilson]]'s seminal book '' | + | Since the appearance of [[E. O. Wilson]]'s seminal book ''Sociobiology: The New Synthesis'' in 1975, ethology has indeed been much more concerned with the social aspects of behavior, such as phenotypic altruism and cooperation. Research has also been driven by a more sophisticated version of evolutionary theory associated with Wilson and [[Richard Dawkins]]. |

| − | Furthermore, a substantial rapprochement with comparative psychology has occurred, so the modern scientific study of | + | Furthermore, a substantial rapprochement with comparative psychology has occurred, so the modern scientific study of behavior offers a more or less seamless spectrum of approaches—from animal cognition to comparative psychology, ethology, and behavioral ecology. ''Evolutionary psychology'', an extension of behavioral ecology, looks at commonalities of cognitive processes in humans and other animals as we might expect natural selection to have shaped them. Another promising subfield is ''neuroethology'', concerned with how the structure and functioning of the brain controls behavior and makes [[learning]] possible. |

| − | == | + | ==List of influential ethologists== |

| − | The | + | The following lis a partial list of scientists who have made notable contributions to the field of ethology (many are comparative psychologists): |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{| width=100% | {| width=100% | ||

| Line 115: | Line 120: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | *Barnard, C. 2004. ''Animal Behaviour: Mechanism, Development, Function and Evolution'' | + | *Barnard, C. 2004. ''Animal Behaviour: Mechanism, Development, Function and Evolution.'' Harlow, England: Pearson/Prentice Hall. ISBN 0130899364. |

| − | * | + | * Burns, C. 2006. Altruism in nature as manifestation of divine ''energeia.'' ''Zygon'' 41(1): 125-137. |

| − | + | *Immelmann, K. 1972. Sexual and other long-term aspects of imprinting in birds and other species. ''Advances in the Study of Behavior'' 4:147–74. | |

| − | + | * Klein, Z. 2000. [http://www.nel.edu/21_6/NEL21062000X001_Klein_.pdf The ethological approach to the study of human behaviour.] ''Neuroendocrinology Letters'' 21:477-81. Retrieved January 13, 2017. | |

| − | * Klein, Z. 2000. [http://www.nel.edu/21_6/NEL21062000X001_Klein_.pdf The ethological approach to the study of human behaviour.] ''Neuroendocrinology Letters'' 21:477-81. | + | *Tinbergen, N. 1991. ''The Study of Instinct.'' Reprint ed. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198577222. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | {{credit|Ethology|136390083}} | + | {{credit|Ethology|136390083|Fixed_action_pattern|138931238|Imprinting_(psychology)|140460744|Neuroethology|113734321|George_Romanes|121936439|Waggle_dance|133603985}} |

[[Category:Life sciences]] | [[Category:Life sciences]] | ||

Latest revision as of 04:36, 22 March 2024

Ethology is a branch of zoology concerned with the study of animal behavior. Ethologists take a comparative approach, studying behaviors ranging from kinship, cooperation, and parental investment, to conflict, sexual selection, and aggression across a variety of species. Today ethology as a disciplinary label has largely been replaced by behavioral ecology and evolutionary psychology. These rapidly growing fields tend to place greater emphasis on social relationships rather than on the individual animal; however, they retain ethology’s tradition of fieldwork and its grounding in evolutionary theory.

The study of animal behavior touches upon the fact that people receive joy from nature and also typically see themselves in a special role as stewards of creation. Behavior is one aspect of the vast diversity of nature that enhances human enjoyment. People are fascinated with the many behaviors of animals, whether the communication "dance" of honeybees, or the hunting behavior of the big cats, or the altruistic behavior of a dolphin. In addition, humans generally see themselves with the responsibility to love and care for nature.

The study of animal behavior also helps people to understand more about themselves. From an evolutionary point of view, organisms of diverse lineages are related through the process of descent with modification. From a religious point of view, human also stand as “microcosms of nature" (Burns 2006). Thus, the understanding of animals helps to better understand ourselves.

Ethologists engage in hypothesis-driven experimental investigation, often in the field. This combination of lab work with field study reflects an important conceptual underpinning of the discipline: behavior is assumed to be adaptive; in other words, something that makes it better suited in its environment and consequently improves its chances of survival and reproductive success.

Ethology emerged as a discrete discipline in the 1920s, through the efforts of Konrad Lorenz, Karl von Frisch, and Niko Tinbergen, who were jointly awarded the 1973 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their contributions to the study of behavior. They were in turn influenced by the foundational work of, among others, ornithologists Oskar Heinroth and Julian Huxley and the American myrmecologist (study of ants) William Morton Wheeler, who popularized the term ethology in a seminal 1902 paper.

Important concepts

One of the key ideas of classical ethology is the concept of fixed action patterns (FAPs). FAPs are stereotyped behaviors that occur in a predictable, inflexible sequence in response to an identifiable stimulus from the environment.

For example, at the sight of a displaced egg near the nest, the greylag goose (Anser anser) will roll the egg back to the others with its beak. If the egg is removed, the animal continues to engage in egg-rolling behavior, pulling its head back as if an imaginary egg is still being maneuvered by the underside of its beak. It will also attempt to move other egg-shaped objects, such as a golf ball, doorknob, or even an egg too large to have been laid by the goose itself (Tinbergen 1991).

Another important concept is filial imprinting, a form of learning that occurs in young animals, usually during a critical, formative period of their lives. During imprinting, a young animal learns to direct some of its social responses to a parent or sibling.

Despite its valuable contributions to the study of animal behavior, classical ethology also spawned problematic general theories that viewed even complex behaviors as genetically hardwired (i.e., innate or instinctive). Models of behavior have since been revised to account for more flexible decision-making processes (Barnard 2003).

Methodology

Tinbergen's four questions for ethologists

The practice of ethological investigation is rooted in hypothesis-driven experimentation. Lorenz's collaborator, Niko Tinbergen, argued that ethologists should consider the following categories when attempting to formulate a hypothesis that explains any instance of behavior:

- Function: How does the behavior impact the animal's chance of survival and reproduction?

- Mechanism: What are the stimuli that elicit the response? How has the response been modified by recent learning?

- Development: How does the behavior change with age? What early experiences are necessary for the behavior to be demonstrated?

- Evolutionary history: How does the behavior compare with similar behavior in related species? How might the behavior have arisen through the evolutionary development of the species, genus, or group?

The four questions are meant to be complementary, revealing various facets of the motives underlying a given behavior.

Using fieldwork to test hypotheses

As an example of how an ethologist might approach a question about animal behavior, consider the study of hearing in an echolocating bat. A species of bat may use frequency chirps to probe the environment while in flight. A traditional neuroscientific study of the auditory system of the bat would involve anesthetizing it, performing a craniotomy to insert recording electrodes in its brain, and then recording neural responses to pure tone stimuli played from loudspeakers. In contrast, an ideal ethological study would attempt to replicate the natural conditions of the animal as closely as possible. It would involve recording from the animal’s brain while it is awake, producing its natural calls while performing a behavior such as insect capture.

Key principles and concepts

Behaviors are adaptive responses to natural selection

Because ethology is understood as a branch of biology, ethologists have been particularly concerned with the evolution of behavior and the understanding of behavior in terms of the theory of natural selection. In one sense, the first modern ethologist was Charles Darwin, whose book The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) has influenced many ethologists. (Darwin’s protégé George Romanes became one of the founders of comparative psychology, positing a similarity of cognitive processes and mechanisms between animals and humans.)

Note, however, that this concept is necessarily speculative. Behaviors are not found as fossils and cannot be traced through the geological strata. And concrete evidence for the theory of modification by natural selection is limited to microevolution—that is, evolution at or below the level of species. The evidence that natural selection directs changes on the macroevolutionary level necessarily involves extrapolation from these evidences on the microevolutionary level. Thus, although scientists frequently allude to a particular behavior having evolved by natural selection in response to a particular environment, this involves speculation as opposed to concrete evidence.

Animals use fixed action patterns in communication

As mentioned above, a fixed action pattern (FAP) is an instinctive behavioral sequence produced by a neural network known as the innate releasing mechanism in response to an external sensory stimulus called the sign stimulus or releaser. Once identified by ethologists, FAPs can be compared across species, allowing them to contrast similarities and differences in behavior with similarities and differences in form (morphology).

An example of how FAPs work in animal communication is the classic investigation by Austrian ethologist Karl von Frisch of the so-called "dance language" underlying bee communication. The dance is a mechanism for successful foragers to recruit members of the colony to new sources of nectar or pollen.

Imprinting is a type of learning behavior

Imprinting describes any kind of phase-sensitive learning (i.e., learning that occurs at a particular age or life stage) during which an animal learns the characteristics of some stimulus, which is therefore said to be "imprinted" onto the subject.

The best known form of imprinting is filial imprinting, in which a young animal learns the characteristics of its parent. Lorenz observed that the young of waterfowl such as geese spontaneously followed their mothers from almost the first day after they were hatched. Lorenz demonstrated how incubator-hatched geese would imprint on the first suitable moving stimulus they saw within what he called a critical period of about 36 hours shortly after hatching. Most famously, the goslings would imprint on Lorenz himself (more specifically, on his wading boots).

Sexual imprinting, which occurs at a later stage of development, is the process by which a young animal learns the characteristics of a desirable mate. For example, male zebra finches appear to prefer mates with the appearance of the female bird that rears them, rather than mates of their own type (Immelmann 1972). Reverse sexual imprinting has also observed: when two individuals live in close domestic proximity during their early years, both are desensitized to later sexual attraction. This phenomenon, known as the Westermarck effect, has probably evolved to suppress inbreeding.

Relation to comparative psychology

In order to summarize the defining features of ethology, it might be helpful to compare classical ethology to early work in comparative psychology, an alternative approach to the study of animal behavior that also emerged in the early 20th century. The rivalry between these two fields stemmed in part from disciplinary politics: ethology, which had developed in Europe, failed to gain a strong foothold in North America, where comparative psychology was dominant.

Broadly speaking, comparative psychology studies general processes, while ethology focuses on adaptive specialization. The two approaches are complementary rather than competitive, but they do lead to different perspectives and sometimes to conflicts of opinion about matters of substance:

- Comparative psychology construes its study as a branch of psychology rather than as an outgrowth of biology. Thus, where comparative psychology sees the study of animal behavior in the context of what is known about human psychology, ethology situates animal behavior in the context of what is known about animal anatomy, physiology, neurobiology, and phylogenetic history.

- Comparative psychologists are interested more in similarities than differences in behavior; they are seeking general laws of behavior, especially relating to development, which can then be applied to all animal species, including humans. Hence, early comparative psychologists concentrated on gaining extensive knowledge of the behavior of a few species, while ethologists were more interested in gaining knowledge of behavior in a wide range of species in order to be able to make principled comparisons across taxonomic groups.

- Comparative psychologists focused primarily on lab experiments involving a handful of species, mainly rats and pigeons, whereas ethologists concentrated on behavior in natural situations.

Since the 1970s, however, animal behavior has become an integrated discipline, with comparative psychologists and ethological animal behaviorists working on similar problems and publishing side by side in the same journals.

Recent developments in the field

In 1970, the English ethologist John H. Crook published an important paper in which he distinguished comparative ethology from social ethology. He argued that the ethological studies published to date had focused on the former approach—looking at animals as individuals—whereas in the future ethologists would need to concentrate on the social behavior of animal groups.

Since the appearance of E. O. Wilson's seminal book Sociobiology: The New Synthesis in 1975, ethology has indeed been much more concerned with the social aspects of behavior, such as phenotypic altruism and cooperation. Research has also been driven by a more sophisticated version of evolutionary theory associated with Wilson and Richard Dawkins.

Furthermore, a substantial rapprochement with comparative psychology has occurred, so the modern scientific study of behavior offers a more or less seamless spectrum of approaches—from animal cognition to comparative psychology, ethology, and behavioral ecology. Evolutionary psychology, an extension of behavioral ecology, looks at commonalities of cognitive processes in humans and other animals as we might expect natural selection to have shaped them. Another promising subfield is neuroethology, concerned with how the structure and functioning of the brain controls behavior and makes learning possible.

List of influential ethologists

The following lis a partial list of scientists who have made notable contributions to the field of ethology (many are comparative psychologists):

|

|

|

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barnard, C. 2004. Animal Behaviour: Mechanism, Development, Function and Evolution. Harlow, England: Pearson/Prentice Hall. ISBN 0130899364.

- Burns, C. 2006. Altruism in nature as manifestation of divine energeia. Zygon 41(1): 125-137.

- Immelmann, K. 1972. Sexual and other long-term aspects of imprinting in birds and other species. Advances in the Study of Behavior 4:147–74.

- Klein, Z. 2000. The ethological approach to the study of human behaviour. Neuroendocrinology Letters 21:477-81. Retrieved January 13, 2017.

- Tinbergen, N. 1991. The Study of Instinct. Reprint ed. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198577222.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

- Ethology history

- Fixed_action_pattern history

- Imprinting_(psychology) history

- Neuroethology history

- George_Romanes history

- Waggle_dance history

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.