Cuban Missile Crisis

The Cuban Missile Crisis was a confrontation during the Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States regarding the Soviet deployment of nuclear missiles in Cuba. The missiles were placed to protect Cuba from further planned attacks by the United States and were rationalized by the Soviets as retaliation for the United States placing deployable nuclear warheads in the United Kingdom, Italy and most significantly, Turkey. The crisis started on October 16, 1962, when U.S. reconnaissance was shown to U.S. President John F. Kennedy revealing Soviet nuclear missile installations on the island, and ended twelve days later on October 28, 1962, when Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev announced that the installations would be dismantled. The Cuban Missile Crisis is regarded as the moment when the Cold War came closest to escalating into a nuclear war. Russians refer to the event as the "Caribbean Crisis," while Cubans refer to it as the "October Crisis."

Background

Fidel Castro took power in Cuba after the Cuban revolution of 1959 and soon took actions inimical to American trade interests on the island. In response, the U.S. stopped buying Cuban sugar and refused to supply its former trading partner with much needed oil. The U.S. government became increasingly concerned about the new regime and this became a major focus of the new Kennedy administration when it took office in January 1961. In Havana, one of the consequences of this was the fear that the United States might intervene against the Cuban government. This fear materialized in later 1961 when Cuban exiles, trained by America's CIA, staged an invasion of Cuban territory at the Bay of Pigs. Although the invasion was quickly repulsed, it intensified a buildup of Cuban defense that was already under way. U.S. armed forces then staged a mock invasion of a Caribbean island in 1962 called Operation Ortsac. The purpose of the invasion was to overthrow a leader whose name was in fact Castro spelled backwards. Although Ortsac was a fictitious name, Castro soon became convinced that the U.S. was serious about invading Cuba. Shortly after the Bay of Pigs invasion Castro declared Cuba to be a socialist republic and entered close ties with the Soviet Union leading to a major upgrade of Cuban military defence

U.S. nuclear advantage

The U.S. had a decided advantage over the Soviet Union in the period leading up to the Cuban Missile Crisis. For the Soviet leaders, the deployment was a necessary response to desperate military situations into which the Soviets had been cornered by a series of remarkable American successes with military equipment and military intelligence. For example, by the close of 1962 the United States had a dramatic advantage in nuclear weapons with more than 300 land-based intercontinental missiles and a fleet of Polaris missile submarines. The Soviet Union for its part had only four to six land-based ICBMs in 1962, and about 100 short-range V-1 type missiles that could be launched from surface submarines.

Few in Washington seriously believed that a few dozen or so ballistic missiles in Cuba could change the essential fact of the strategic balance of power: the Soviet Union was hopelessly outgunned. By the fall of 1962, America’s arsenal contained 3,000 nuclear warheads and nearly 300 in espionage. Before his arrest on the first day of the Cuban missile crisis, Colonel Oleg Penkovsky had served as an intelligence agent for the Americans and British. He was also a colonel in Soviet Intelligence. Melman notes that "the proceedings of his trial in April 1963 revealed that he had delivered 5,000 frames of film of Soviet military-technical information, apart from many hours of talk with western agents during several trips to western Europe". Melman argues that top officers in the Soviet Union concluded "that the US then possessed decisive advantage in arms and intelligence, and that the USSR no longer wielded a credible nuclear deterrent". (Melman, 1988: 119)

In 1961, the U.S. started deploying 15 Jupiter IRBM (intermediate-range ballistic missiles) nuclear missiles near İzmir, Turkey, which directly threatened cities in the western sections of the Soviet Union. These missiles were regarded by President Kennedy as being of questionable strategic value; an SSBN (ballistic submarine) was capable of providing the same cover with both stealth and superior firepower.

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had publicly expressed his anger at the Turkish deployment, and regarded the missiles as a personal affront. The deployment of missiles in Cuba — the first time Soviet missiles were moved outside the USSR — is commonly seen as Khrushchev's direct response to the Turkish missiles.

Soviet Medium-Range Ballistic Missiles on Cuban soil, with a range of 2,000 km (1,200 statute miles), could threaten Washington, DC and around half of the U.S.'s SAC bases (of nuclear-armed bombers), with a flight time of under twenty minutes. In addition, the U.S.'s radar warning systems oriented toward the USSR would have provided little warning of a launch from Cuba.

Missile deployment

Khrushchev devised the deployment plan in May of 1962, and by late July over sixty Soviet ships were en route to Cuba, some of them already carrying military material. John McCone, director of the CIA had recently been on honeymoon to Paris where he had been told by French Intelligence that the Soviets were planning to place missiles in Cuba and so he warned President Kennedy that some of the ships were probably carrying missiles; however, John and Robert Kennedy, Dean Rusk, and Robert McNamara concluded that the Soviets would not try such a thing. Kennedy's administration had received repeated claims from Soviet diplomats that there were no missiles in Cuba, nor any plans to place any, and that the Soviets were not interested in starting an international drama that might impact the US elections in November.

The U-2 flights

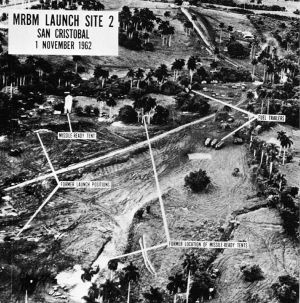

A U-2 flight in late August photographed a new series of SAM (surface-to-air missile) sites being constructed, but on September 4, 1962 Kennedy told Congress that there were no offensive missiles in Cuba. On the night of September 8, the first consignment of SS-4 MRBMs was unloaded in Havana, and a second shipload arrived on September 16. The Soviets were building nine sites — six for SS-4s and three for SS-5s with a range of 4,000 km (2,400 statute miles). The planned arsenal was forty launchers, an increase in Soviet first strike capacity of 70%. This matter was readily noticed by Cubans in Cuba and perhaps as many as a thousand reports of such reached Miami, and were evaluated and then considered spurious by US intelligence [1].

A number of unconnected problems meant that the missiles were not discovered by the US until a U-2 flight of October 14 clearly showed the construction of an SS-4 site near San Cristobal. The photographs were shown to Kennedy on October 16 [2]. By October 19 the U-2 flights (then almost continuous) showed four sites were operational. Initially, the U.S. government kept the information secret, telling only the fourteen key officials of the executive committee. The United Kingdom was not informed until the evening of October 21. President Kennedy, in a televised address on October 22, announced the discovery of the installations and proclaimed that any nuclear missile attack from Cuba would be regarded as an attack by the Soviet Union and would be responded to accordingly. He also placed a naval "quarantine" (blockade) on Cuba to prevent further Soviet shipments of military weapons from arriving there. The word quarantine was used rather than blockade for reasons of international law (the blockade took place in international waters) and in keeping with the Quarantine Speech of 1937 by Franklin D. Roosevelt. Kennedy reasoned that a blockade would be an act of war (which was correct) and war had not been declared between the U.S. and Cuba. A U-2 flight was shot down by an SA-2 Guideline SAM emplacement October 27, causing negotiation stress between the USSR and USA.

Kennedy's Options

After the Bay of Pigs disaster, the USSR sent conventional missiles, jet fighters, patrol boats and 5000 soviet soldiers and scientists to Cuba. But the U.S.A still didn't know if nuclear weapons were based there on Cuba. The USSR at this stage were still denying such claims. Then in Oct 1962, U-2 spy planes photographed missile sites being set up. At that point it is said that JFK had several courses of action open to him:

1. Do Nothing- For: USA had more nuclear power at the time and this would scare USSR away from conflict. Against: Khrushchev and co. would see this as a sign of weakness.

2. Perform a Surgical Air Attack (destroying nuclear bases)- For: It would destroy the missiles before they were used. Against: 1. Couldn't guarantee destruction of all the missiles 2. Soviet lives would be lost 3. Could be seen as immoral, attacking without warning.

3. Invasion- For: Invasion would deal with Castro and missiles, US soldiers were trained well for this. Against: There would be a strong Soviet response.

4. Use Diplomatic Pressures (e.g using UN etc to intervene)- For: It would avoid conflict. Against: If USA was told to back down it could be a sign of weakness.

5. Blockade- For: It would show USA was serious but at the same time would not be a direct act of war. Against: It wouldn't solve the main problem- the missiles already in Cuba.

U.S. response

With the news of the confirmed photographic evidence of Soviet missile bases in Cuba, President Kennedy convened a special group of senior advisers to meet secretly at the White House. This group later became known as the ExComm, or Executive Committee of the National Security Council. From the morning of October 16 this group met frequently to devise a response to the threat. An immediate bombing strike was dismissed early on, as was a potentially time-consuming appeal to the United Nations. They were eventually able to put out the possibility of diplomacy, narrowing the choice down to a naval blockade and an ultimatum, or full-scale invasion. A blockade was finally chosen, although there were a number of conservatives (notably Paul Nitze, and Generals Curtis LeMay and Maxwell Taylor) who kept pushing for tougher action. An invasion was planned, and troops were assembled in Florida. However US intelligence was flawed: they believed Soviet and Cuban troop numbers on Cuba to be around 10,000 and 100,000, when they were in fact around 43,000 and 270,000 respectively [3]. Also, they were unaware that 12 kiloton-range nuclear warheads had already been delivered to the island and mounted on FROG-3 "Luna" short-range artillery rockets, which could be launched on the authority of the Soviet commander on the island, General Pliyev, [4] in the event of an invasion. Though they posed no threat to the continental US, an invasion would probably have precipitated a nuclear strike against the invading force, with catastrophic results.

There were a number of issues with the naval blockade. There was legality - as Fidel Castro noted, there was nothing illegal about the missile installations; they were certainly a threat to the U.S., but similar missiles aimed at the U.S.S.R. were in place in Europe (sixty Thor IRBMs in four squadrons near Nottingham, in the United Kingdom; thirty Jupiter IRBMs in two squadrons near Gioia del Colle, Italy; and fifteen Jupiter IRBMs in one squadron near İzmir, Turkey). There was concern of the Soviet's reaction to the blockade; it might turn into escalating retaliation.

Kennedy spoke to the American public, and to the Soviet government, in a televised address on October 22. He confirmed the presence of the missiles in Cuba and announced the naval blockade as a quarantine zone of 500 nautical miles (926 km) around the Cuban coast. He warned that the military was "prepared for any eventualities", and condemned the Soviet Union for "secrecy and deception". The U.S. was surprised at the solid support from its European allies, particularly from the notoriously difficult President Charles de Gaulle of France. Nevertheless, Britain's prime minister Macmillan, as well as much of the international community, did not understand why a diplomatic solution was not considered.

The case was conclusively proved on October 25 at an emergency session of the UN Security Council. U.S. Ambassador Adlai Stevenson attempted to force an answer from Soviet Ambassador Valerian Zorin as to the existence of the weapons, famously demanding, "Don't wait for the translation!" Upon Zorin's refusal, Stevenson produced photographs taken by U.S. surveillance aircraft showing the missile installations in Cuba.

Khrushchev sent letters to Kennedy on October 23 and 24 claiming the deterrent nature of the missiles in Cuba and the peaceful intentions of the Soviet Union; however, the Soviets had delivered two different deals to the United States government. On October 26, they offered to withdraw the missiles in return for a U.S. guarantee not to invade Cuba or support any invasion. The second deal was broadcast on public radio on October 27, calling for the withdrawal of U.S. missiles from Turkey in addition to the demands of the 26th. The crisis peaked on October 27, when a U-2 (piloted by Rudolph Anderson) was shot down over Cuba and another U-2 flight over Russia was almost intercepted when it strayed over Siberia. This was after Curtis LeMay (U.S. Air Force Chief of Staff) had neglected to enforce Presidential orders to suspend all overflights. At the same time, Soviet merchant ships were nearing the quarantine zone. Kennedy responded by publicly accepting the first deal and sending Robert Kennedy to the Soviet embassy to accept the second in private that the fifteen Jupiter missiles near İzmir, Turkey would be removed six months later. Kennedy also requested that Khrushchev keep this second compromise out of the public domain so that he did not appear weak before the upcoming election. This had ramifications for Khrushchev later. The Soviet ships turned back and on October 28, Khrushchev announced that he had ordered the removal of the Soviet missiles in Cuba. The decision prompted then Secretary of State Dean Rusk to comment, "We are eyeball to eyeball, and the other fellow just blinked."

Satisfied that the Soviets had removed the missiles, President Kennedy ordered an end to the quarantine of Cuba on November 20.

Aftermath

Template:Contradict-section

The compromise satisfied no one, though it was a particularly sharp embarrassment for Khrushchev and the Soviet Union because the withdrawal of American missiles from Turkey was not made public. They were seen as retreating from circumstances that they had started — though if played well, it could have looked like just the opposite: the USSR gallantly saving the world from nuclear holocaust by not insisting on restoring the nuclear equilibrium. Khrushchev's fall from power two years later can be partially linked to Politburo embarrassment at both Khrushchev's eventual concessions to the US and his ineptitude in precipitating the crisis in the first place.

U.S. military commanders were not happy with the result either. General LeMay told the President that it was "the greatest defeat in our history" and that the US should invade immediately.

For Cuba, it was a betrayal by the Soviets whom they had trusted, given that the decisions on putting an end to the crisis had been made exclusively by Kennedy and Khrushchev.

In early 1992 it was confirmed that key Soviet forces in Cuba had, by the time the crisis broke, received tactical nuclear warheads for their artillery rockets, and IL-28 bombers [5], though General Anatoly Gribkov, part of the Soviet staff responsible for the operation, stated that the local Soviet commander, General Issa Pliyev, had predelegated authority to use them if the U.S. had mounted a full-scale invasion of Cuba. Gribkov misspoke: the Kremlin's authorization remained unsigned and undelivered. (Other accounts show that Pliyev was given permission to use tactical nuclear warheads but only in the most extreme case of an American invasion during which contact with Moscow is lost. However when American forces seemed to be readying for an attack, (after the U2 photos, but before Kennedy's television address), Khrushchev rescinded his earlier permission for Pliyev to use the tactical nuclear weapons, even under the most extreme conditions. Whether because of the clear American nuclear dominance, or simply out of benevolence, Khrushchev wanted to avoid nuclear war at all costs.)

The Cuban Missile Crisis spurred the creation of the Hot Line, a direct communications link between Moscow and Washington D.C. The purpose of this undersea line was to have a way the leaders of the two Cold War countries could communicate directly to better solve a crisis like the one in October 1962.

The short time span of the Cuban Missile Crisis and the extensive documentation of the decision-making processes on both sides makes it an excellent case study for analysis of state decision-making. In the Essence of Decision, Graham T. Allison and Philip D. Zelikow use the crisis to illustrate multiple approaches to analyzing the actions of the state. The intensity and magnitude of the crisis also provides excellent material for drama, as illustrated by the movies The Missiles of October (1974), a television docudrama directed by Anthony Page and starring William Devane, Ralph Bellamy, Howard Da Silva and Martin Sheen, and Thirteen Days (2000), directed by Roger Donaldson and starring Kevin Costner, Bruce Greenwood and Steven Culp. It was also a substantial part of the 2003 documentary The Fog Of War, which won an Oscar.

In October 2002, McNamara and Schlesinger joined a group of other dignitaries in a "reunion" with Castro in Cuba to continue to release classified documents and further study the crisis. It was during the first meeting that Secretary McNamara first discovered that Cuba had many more missiles than initially expected, and what McNamara referred to as 'rational men' (Castro and Khruschev) were perfectly willing to start a nuclear war over the crisis. Furthermore, it was revealed at this conference that an officer aboard a Soviet submarine, named Vasili Alexandrovich Arkhipov, may have single-handedly prevented the initiation of a nuclear catastrophe [6]. The reported details of this event are remarkably similar to the plot from the movie Crimson Tide (1995), except that the roles of the Americans and Soviets are reversed.

Various commentators (Melman, 1988; Hersh, 1997) also suggest that the Cuban Missile Crisis enhanced the hubris of American military planners, leading to military adventurism, most decidedly in Vietnam.

See also

- International crisis

- Cold War

- Brinkmanship

- Cuba-United States relations

- Cuban-Soviet relations

- Thirteen Days - book written by Robert F. Kennedy

- The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons from the Life of Robert S. McNamara

Reading on the Cuban missile crisis

- Allison, Graham T. and Zelikow, Philip. Essence of Decision: Explaining the Cuban Missile Crisis. New York : Longman, c1999 ISBN 0321013492

- Blight, James G. and David A. Welch. On the Brink: Americans and Soviets Reexamine the Cuban Missile Crisis. New York : Noonday, 1990 ISBN 0374522278 With a foreword by McGeorge Bundy.

- Brugioni, Dino A. Eyeball to Eyeball: The Inside Story of the Cuban Missile Crisis. New York : Random House, c1991 ISBN 0679405232 Edited by Robert F. McCort.

- Chayes, Abram. The Cuban Missile Crisis, International Crisis and the Role of Law. Lanham, MD : University Press of America, c1987 ISBN 0819167177

- Diez Acosta, Tomás. October 1962: The 'Missile' Crisis As Seen From Cuba. New York : Pathfinder, 2002 ISBN 087348956X

- Divine, Robert A. The Cuban Missile Crisis; New York: M. Wiener Pub.,1988.

- Frankel, Max, High Noon in the Cold War; Ballantine Books, 2004; Presidio Press (reprint), 2005; ISBN 0345466713.

- Fursenko, Aleksandr, and Naftali, Timothy; One Hell of a Gamble - Khrushchev, Castro and Kennedy 1958-1964; W.W. Norton (New York 1998)

- Gonzalez, Servando The Nuclear Deception: Nikita Khrushchev and the Cuban Missile Crisis; IntelliBooks, 2002; ISBN 0-9711391-5-6.

- Kennedy, Robert F. Thirteen Days: A Memoir of the Cuban Missile Crisis; ISBN 0-3933183-4.

- Khrushchev, Sergei, How my father and President Kennedy saved the world; American

Heritage magazine, October 2002 issue.

- May, Ernest R. (editor); Zelikow, Philip D. (editor), The Kennedy Tapes : Inside the White House during the Cuban Missile Crisis; Belknap Press, 1997; ISBN 0674179269.

- Polmar, Norman and Gresham, John D. (foreword by Clancy, Tom) DEFCON – 2: Standing on the Brink of Nuclear War During the Cuban Missile Crisis; Wiley, 2006; ISBN 0471670227.

- Pope, Ronald R., Soviet Views on the Cuban Missile Crisis: Myth and Reality in Foreign Policy Analysis; University Press of America, 1982.

- Stern, Sheldon M., Averting the Final Failure: John F. Kennedy and the Secret Cuban Missile Crisis Meetings; Stanford University Press, 2003.

- Bamford, James, Body of Secrets: Anatomy of the Ultra-Secret National Security Agency; Anchor Books, 2002.

- Giglio, James N. The Presidency of John F. Kennedy; Lawrence, Kansas, 1991.

- Hersh, Seymour. The Dark Side of Camelot; Hammersmith, London: HarperCollins Publishers, 1997.

- Melman, Seymour. The Demilitarized Society: Disarmament and Conversion; Nottingham: Spokesman Books, 1988.

Fiction based on the historical crisis

- DuBois, Brendan, Resurrection Day; G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1999.

- Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater; Konami, 2004.

- Cuban Missile Crisis: The Aftermath ; G5 Software 2005.

- seaQuest DSV; episode entitled "Second Chance."

External links

- IV. Chronology of Submarine. Contact During the Cuban Missile Crisis. October 1, 1962 - November 14, 1962. Prepared by Jeremy Robinson-Leon and William Burr.

- Declassified Documents, etc. - Provided by the National Security Archive.

- Transcripts and Audio of ExComm meetings - Provided by the Miller Center's Presidential Recordings Program, University of Virginia.

- Forty Years After 13 Days - Robert S. McNamara.

- Tapes of debates between JFK and his advisors during the crisis

- Cuban Missile Crisis Reunion, October 2002

- The World On the Brink: John F. Kennedy and the Cuban Missile Crisis

- 14 Days in October: The Cuban Missile Crisis - a site geared toward high-school students

- Nuclear Files.org Introduction, timeline and articles regarding the Cuban Missile Crisis

- Cuba Havana Documentary Bye Bye Havana is a documentary revealing what Cubans are thinking about today

- Annotated bibliography on the Cuban Missile Crisis from the Alsos Digital Library.

- October, 1962: DEFCON 4, DEFCON 3, DEFCON 2

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.