Cave of the Patriarchs

The Cave of the Patriarchs (Hebrew: מערת המכפלה, Me'arat HaMachpela, Trans. "Cave of the Double Tombs") is a series of subterranean caves located in a complex called by Muslims the Ibrahimi Mosque or Sanctuary of Abraham (Arabic: الحرم الإبراهيمي, Al-Haram Al-Ibrahimi ▶). The name is either a reference to the layout of the burial chamber, or alternatively refers to the biblical couples, i.e: cave of the tombs of couples.

The compound, located in the ancient city of Hebron, is the second holiest site for Jews (after the Temple Mount in Jerusalem) and is also venerated by Christians and Muslims all of whose traditions maintain that the site is the burial place of four Biblical couples: (1) Adam and Eve; (2) Abraham and Sarah; (3) Isaac and Rebekah; (4) Jacob and Leah, though some Christians maintain a tradition that the skull of Adam, is buried under Golgotha. According to Midrashic sources the Cave of the Patriarchs also contains the head of Esau, and according to some Islamic sources it is also the tomb of Joseph.

Biblical origin

According to the Book of Genesis, the Biblical patriarch Abraham purchased the site from Ephron the Hittite as a family burial plot after the death of his wife Sarah. The Bible gives the sum Abraham paid for the cave as 400 silver shekels.[1] The text refers to the cave as the cave of Machpelah, and elsewhere designates it as the cave of the field of the Machpelah, suggesting that the term Machpelah may actually be intended to describe the area in which the field containing the cave was located, near Mamre.[2]

The Hittite empire did not extend into Canaan until the late 14th century B.C.E., only just before The Exodus (which the Bible places many generations after Abraham) in traditional chronologies, and over a century after the date in the New Chronology of David Rohl. In the 19th century B.C.E., or 21st century B.C.E., the dates in the respective chronologies for Abraham, Hittites barely existed as a distinct people. It is also possible, however, that Hittite, in this case, does not refer to the distinct national group. The Hebrew word can also be rendered Son of Heth and so could refer only to Heth's children and/or grandchildren.

Post-Biblical history

Structural changes

Herod the Great built a large rectangular enclosure over the caves, the only fully surviving Herodian structure. Herod's building, with 6-foot-thick stone walls made from stones that were at least 3 feet tall and sometimes reach a length of 24 feet, did not have a roof. Archæologists are not certain where the original entrance to the enclosure was located, or even if there was one.[3]

Until the era of the Byzantine Empire, the interior of the enclosure remained exposed to the sky. Under Byzantine rule, a simple basilica was constructed at the southeastern end, and the enclosure was roofed everywhere except at the centre. In 614, the Persians conquered the area and destroyed the church, leaving only ruins; but in 637, the area came under the control of the Muslims, and the building was reconstructed as a roofed mosque.

During the 10th century, an entrance was pierced through the north-eastern wall, some way above the external ground level, and steps from the north and from the east were built up to it (one set of steps for entering, the other for leaving).[3] A building known as the kalah (castle) was also constructed near the middle of the southwestern side; its purpose is unknown but one historic account claims that it marked the spot where Joseph was buried (cf Joseph's tomb), the area having been excavated by a muslim caliph, under the influence of a local tradition regarding Joseph's tomb.[3] Some archaeologists believe that the original entrance to Herod's structure was in the location of the kalah, and that the northeastern entrance was created so that the kalah could be built by the former entrance.[3]

In 1100, the enclosure once again became a church, after the area was captured by the Crusaders, and Muslims were no longer permitted to enter; during this period the area was given a new gabled roof, clerestory windows, and vaulting. However, in 1188, Saladin conquered the area, reconverting the enclosure to a mosque, but allowing Christians to continue worshipping there. Saladin also added a minaret at each corner - two of which still survive - and the minbar.[3]

In the late 14th century, under the Mamluks, two additional entrances were pierced into the western end of the south western side, and the kalah was extended upwards to the level of the rest of the enclosure; a cenotaph in memory of Joseph was created in the upper level of the kalah, so that visitors to the enclosure would not need to leave and travel round the outside just to pay respects.[3] The Mamluks also built the northwestern staircase and the six cenotaphs (for Isaac, Rebekah, Jacob, Leah, Abraham, and Sarah, respectively), distributed evenly throughout the enclosure. The Mamluks forbade Jews from entering the site, only allowing them as close as the 5th step on a staircase at the southeast, but after some time this was increased to the 7th step.

Security and conflict

After the Six Day War, the area came under the control of Israel, and the restriction limiting Jews to the 7th step was lifted. In 1994 Baruch Goldstein took an assault rifle into the enclosure and killed 29 Palestinian Muslims who had been at prayer, as well as injuring 125 others, before being bludgeoned to death by survivors. The resulting riots left an additional 26 Palestinians and 9 Israelis dead, and the incident provoked national and international condemnation of Goldstein's actions.

The increased sensitivity of the site meant that in 1995 the Wye River Accords, part of the Arab-Israeli peace process, included a temporary status agreement for the site, restricting access for both Jews and Muslims. As part of this agreement, the waqf controls 81% of the building, including the whole of the southeastern section, which lies above the only known entrance to the caves, and possibly over the entirety of the caves themselves. In consequence, Jews are not permitted to visit the Cenotaphs of Isaac or Rebekah, which lie entirely within the southeastern section, except for 10 days a year which hold special significance in Judaism. One of these days is the Shabbat of Chayei Sarah, when the Jews read the Torah portion concerning the death of Abraham and Sarah, and that concerning the purchase by Abraham of the land in which the caves are situated.

The Israeli authorities do not allow Jewish religious authorities the right to maintain the site, and only allow the waqf to do so. Tourists are permitted to enter the site. Security at the site has increased since the Intifada, and the Israel Defense Forces surround the site with soldiers, and control access to the shrine; there are additional restrictions placed on access by Palestinians beyond the restrictions imposed on Muslims in general by the Wye River Accords.

Present structure

The rectangular stone enclosure lies on a northwest-southeast axis, and is divided into two sections by a wall running between the northwestern three fifths, and the southeastern two fifths. The northwestern section is roofed on three sides, the central area and north eastern side being open to the sky; the southeastern section is fully roofed, the roof being supported by four columns evenly distributed through the section.

In the northwestern section are four cenotaphs, each housed in a separate octagonal room, those dedicated to Jacob and Leah being on the northwest, and those to Abraham and Sarah on the southeast. A corridor runs between the cenotaphs on the northwest, and another between those on the southeast. A third corridor runs the length of the southwestern side, through which access to the cenotaphs, and to the southeastern section, can be gained. An entrance to the enclosure exists on the southwestern side, entering this third corridor; a mosque outside this entrance must be passed through to gain access.

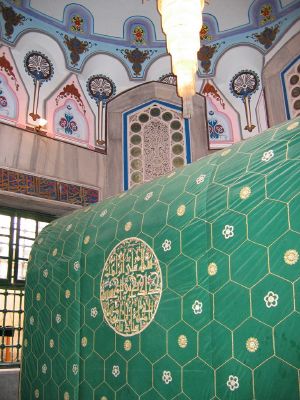

At the centre of the northeastern side, there is another entrance, which enters the roofed area on the southeastern side of the northwestern section, and through which access can also be gained to the southeastern (fully roofed) section. This entrance is approached on the outside by a corridor which leads from a long staircase running most of the length of the northwestern side.[4] The southeastern section, which functions primarily as a mosque, contains two cenotaphs, symmetrically placed, near the centre, dedicated to Isaac and Rebekah. Between them, in the southeastern wall, is a mihrab. The cenotaphs have a distinctive red and white horizontal striped pattern to their stonework, but are usually covered by decorative cloth.

Under the present arrangements, Jews are restricted to entering by the southwestern side, and limited to the southwestern corridor and the corridors which run between the cenotaphs, while Muslims may only enter by the northeastern side, and are restricted to the remainder of the enclosure.

The caves

The caves under the enclosure are not themselves generally accessible; the waqf have historically prevented access to the actual tombs out of respect for the dead. Only two entrances are known to exist, the most visible of which is located to the immediate southeast of Abraham's cenotaph on the inside of the southeastern section. This entrance is a narrow shaft covered by a decorative grate, which itself is covered by an elaborate dome. The other entrance is located to the southeast, near the minbar, and is sealed by a large stone, and usually covered by prayer mats; this is very close to the location of the seventh step on the outside of the enclosure, beyond which the Mamelukes forbade Jews from approaching.

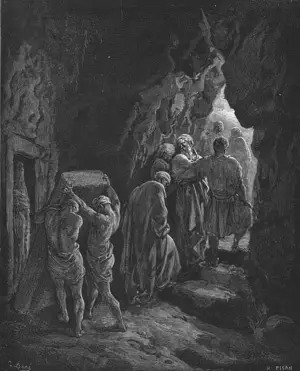

When the enclosure was controlled by crusaders, access was occasionally possible. One account, by Rabbi Benjamin of Tudela dating from 1163 C.E., states that after passing through an iron door, and descending, the caves would be encountered. According to Benjamin of Tudela, there was a sequence of three caves, the first two of which were empty; in the third cave were six tombs, arranged to be opposite to one another.[6]

These caves had only been rediscovered in 1119 C.E., by a monk named Arnoul, who had noticed a draught in the area near where the minbar is at present, and had removed the flagstones and found a room lined with Herodian masonry. Arnoul, still searching for the source of the draught, hammered on the cave walls until he heard a hollow sound, pulled down the masonry in that area, and discovered a narrow passage. The narrow passage, which subsequently became known as the serdab (Arabic for passage), was similarly lined with masonry, but partly blocked up; having unblocked the passage Arnoul discovered a large round room with plastered walls. In the floor of the room he found a square stone slightly different from the others, and upon removing it found the first of the caves. The caves were filled with dust, and after removing the dust, Arnoul found bones; believing the bones to be those of the Biblical Patriarchs, Arnoul washed them in wine, and stacked them neatly. Arnoul carved inscriptions into the caves describing whose bones he believed them to be.[3]

This passage to the caves was sealed at some time after Saladin had recaptured the area, though the roof of the circular room was pierced, and a decorative grate was placed over it. In 1967, after the Six Day War, the area fell into the hands of the Israeli Defence Force, and Moshe Dayan, the Defence Minister, and an amateur archaeologist, attempted to regain access to the tombs. Dayan, not knowing about the serdab entrance, started investigating the shaft visible beyond the decorative grate, and came up with the idea of sending someone thin enough through the shaft and down into the chamber below. Dayan eventually found a slim girl named Michal and sent her into the chamber.[7]

Michal explored the round chamber, but failed to spot the stone in the floor that led to the caves; Michal did however explore the passage and find steps leading up to the surface, though the exit was blocked by a large stone (this is the entrance near the minbar).[3] According to the report of her findings, which Michal gave to Dayan after having been lifted back through the shaft, there are 16 steps leading down into the passage, which is 1 cubit wide, 17.37 m and 1 m high. In the round chamber, which is 12 m below the entrance to the shaft, there are three stone slabs, the middle one of which contains a partial inscription of Sura 2, verse 255, from the Qu'ran.[3]

A few English language Christian Zionist websites [1][2], claim that Seev Jevin, a former director of the Israel Antiquities Authority, gave an interview to Nachrichten aus Israel, a German Christian Fundamentalist news website, in which he claimed to have entered the passage in 1981. According to these reports, Jevin was permitted by the waqf to enter the chamber via the entrance near the mihrab, and upon doing so discovered the square stone in the round chamber that concealed the cave entrance; the reports state that after entering the first cave, which Jevin regarded as empty, he found a passage leading to a second oval chamber, smaller than the first, which contained shards of pottery and a wine jug. The claims concerning this interview and its accuracy are unconfirmed.

Religious stances

Both Judaism and Islam agree that entombed within are the Biblical and Qur'anic patriarchs (Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob) as well as three matriarchs (Sarah, Rebekah, and Leah), and also Adam and Eve.

Judaism

In Judaism, the Tombs of the Patriarchs is the second most sacred site in the world, after Temple Mount,[3][4]. It represents the first material purchase of real estate by Abraham in the Land of Canaan (the "Promised Land") and according to Jewish tradition, four patriarchal couples mentioned in the Book of Genesis are buried there:

- Adam and Eve

- Abraham and Sarah

- Isaac and Rebekah

- Jacob and Leah - Jacob's other wife, Rachel, being buried near Bethlehem according to tradition.

According to the midrash, the Patriarchs were buried in the cave because the cave is the threshold to the Garden of Eden. The Patriarchs are said not to be dead but "sleeping." They rise to beg mercy for their children throughout the generations. According to the Zohar,[8] this tomb is the gateway through which souls enter into Gan Eden—heaven.

There is a Jewish tradition that praying at the Tomb will bring good fortune in finding a proper spouse. There are Hebrew prayers of supplication for marriage on the walls of the Sarah cenotaph.

Islam

The enclosure is known to Muslims as the Ibrahimi Mosque, as Abraham is a revered prophet of Islam who, according to the Qur'an, built the Kaaba in Mecca with his son Ishmael. After the conquest of the city by Umar the Herodian enclosure was rebuilt as a mosque for this reason, and placed under the control of a waqf - a traditional "trust" holding land for Islamic religious purposes. The waqf continues to control and maintain most of the site.

Notes

- ↑ Genesis 22

- ↑ "Genesis 22:17-18", Holy Bible. “So Ephron's field in Machpelah near Mamre—both the field and the cave in it, and all the trees within the borders of the field—was deeded to Abraham as his property in the presence of all the Hittites who had come to the gate of the city.”

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 Biblical Archaeology Review, Patriarchal Burial Site Explored for First Time in 700 Years, May/June 1985

- ↑ a floorplan. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ A wider image of the same side..

- ↑ International Standard Bible Encyclopedia

- ↑ photograph of Michal descending through the grated shaft. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- ↑ Zohar 127a

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Gellman, Jerome. Abraham! Abraham: Kierkegaard and the Hasidim on the Binding of Isaac. London: Ashgate Publishing, 2003. ISBN 978-0754616795

- Heap, Norman. Abraham, Isaac and Jacob: Servants and Prophets of God. Greensboro, NC: Family History Publications, 1999. ISBN 978-0945905028

- Moore, Beth. The Patriarchs: Encountering the God of Abraham, Issac and Jacob- Leader Guide. Lifeway Christian Resources, 2005. ISBN 9780633197537

- Rosenberg, David. Abraham: The First Historical Biography. New York: Basic Books, new edition, 2007. ISBN 978-0465070954

- Ware, Timothy. The Orthodox Church: New Edition. Penguin (Non-Classics); 2 edition, 1993. ISBN 9780140146561

- Wilson, Marvin R. Our Father Abraham: Jewish Roots of the Christian Faith. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1989. ISBN 978-0802804235

- Whelton, Michael. Popes and Patriarchs: An Orthodox Perspective on Roman Catholic Claims. Conciliar Press, 2006. ISBN 9781888212785

External links

- Official Website (Israeli) Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- The Cave of Machpelah Tomb of the Patriarch Jewish Virtual Library. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- Tombs of the Patriarchs Article and Photos Sacred Destinations. Retrieved September 19, 2008.

- Demands for Equal Rights for the Jewish People at Ma'arat HaMachpela Retrieved September 19, 2008.Hebron.org.il

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.